| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Voyage in Lower and Upper Egypt, during the Campaigns of General Bonaparte. Vivant Denon | | | | |

|

Chapter 42: Syene. - Elephantine Island. (p.204)

I

went with General Belliard to take possession for the government of

Syene. During my stay in this city, my drawings will supplement my

diary and replace it.

I

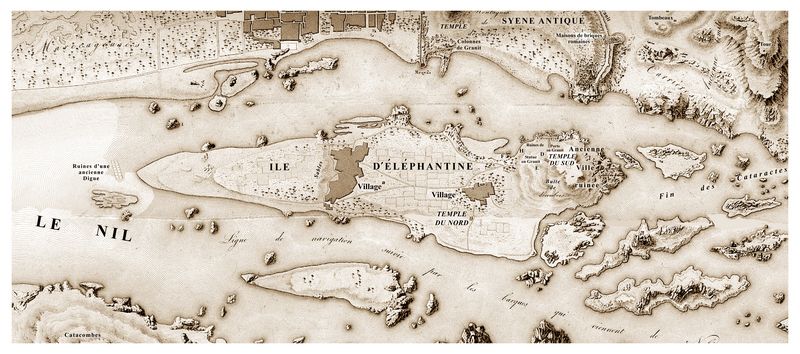

first made the view that I have just described, which is a kind of

bird's eye map, in which one can see at a glance the general picture of

the country, the entrance of the Nile into Egypt crossing the granite

bank which forms its last cataracts, Elephantine Island between

Contra-Syene and Syene, the monuments of this city, in which we can

distinguish the various eras, or rather the periods of its existence.

The ruins of its earliest antiquity are easily recognized; it must then

have been a very considerable city, if the buildings on the right and

left of the Nile and those of Elephantine formed only one city, as one

must believe, since they are only separated by the river, which in this

place is deeper than wide: the Arab ruins are grouped on a rock at

Test; at the bottom, are Roman monuments, which are also found in

structures on Elephantine Island: all this was succeeded by a large

village, better built, with straighter streets than ordinary villages;

which must be attributed to the presence of the stone and the quantity

of ancient materials. In the middle is a Turkish castle hidden on all

sides, and which cannot be of any defense.

In my first walks, I

drew the profiles of the objects of which I had made the map; and

getting closer to the rock on which the ancient Arab city was located,

I made that of Elephantine Island and its monuments, the site of which

can be seen before understanding its details.

We spent (p.205)

our first moments establishing ourselves: we had a fairly nice

neighborhood; It was the kiachef's house, built of stone, with one

floor, terraces, and vaulted apartments: we made beds, tables, benches;

undressing, sitting down and lying down seemed to me to be indulgence,

a real pleasure: the soldiers did the same. On the second day of our

establishment there were already in the streets of Syene tailors,

shoemakers, goldsmiths, French barbers with their brands, caterers and

restaurateurs at fixed prices. The station of an army presents the

picture of the most rapid development of the resources of industry;

each individual implements all his means for the good of society: but

what particularly characterizes a French army is to establish the

superfluous at the same time and with the same care as the necessary;

there were gardens, cafes, and public games, with cards made in Syene.

At the exit of the village an avenue of aligned trees headed north; the

soldiers placed a mile column there with the inscription, Route de

Paris, n° eleven hundred and sixty-seven thousand three hundred and

forty: it was a few days after having received a distribution of dates

for all rations that they had such ideas pleasant or philosophical.

Only death can put an end to so much bravery and cheerfulness; the

greatest misfortunes can do nothing about it.

On this side of

the river there is no other remains of the Egyptian city than a small

square temple surrounded by a gallery, but so destroyed and so

shapeless that we can only see the embrasure of the two intercolumns,

with the capitals, and a small part of the entablature: this fragment

is what Savari, who confesses not to have come to Syene, indicates on

his word as possibly being the remains of the observatory, in which it

is necessary , according to him, look for the nilometer. I made the

particular drawing of this little ruin, to destroy an error of which we

cannot accuse our ardent and elegant (p.206) traveler, who searched for

everything, indicated everything, and who often painted marvelously

even what he had not seen.

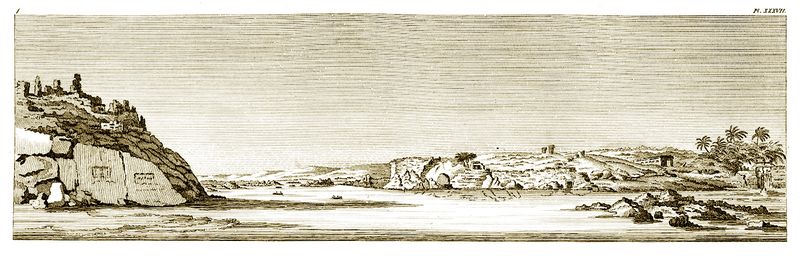

"No.

1.—View of Elephantine, taken from the foot of the rocks, on which are

perched the ruins of the ancient fortified city of the Arabs in the

time of the Caliphs, where we can still see Egyptian inscriptions on

the granite hillocks which served as a base for this city; to the left

of the print the profile of Elephantine Island, the rocks and the

ancient coverings which defend the southern part from the efforts of

the Nile current, and from the weight of the mass of its waters at the

time of the flood; granite hillocks covered with hieroglyphics; a

portion of the quay, bearing the remains of an open gallery overlooking

the river; at river water level a door opening onto a granite

staircase, which may have served as a nilometer; above a series of

ruins of Egyptian monuments, composed of corridors; small rooms

decorated with very careful hieroglyphic sculptures -; this continuity

of ruins seems to join and arrive at the factories which surrounded a

temple. Quite to the right of the print, among the palm trees, a pot

chain for raising the water, placed on a construction against which is

inlaid a bas-relief in white marble, Roman work, representing the

figure of the Nile in the same attitude of that of the statue of this

river which is at the Belvedere in Rome." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Elephantine Island became at once my

country home, my place of delights, observation, and research; I

believe I have turned over all the stones there, and questioned all the

rocks that make it up: it was in its southern part that the Egyptian

city and the Roman and Arab dwellings that succeeded it were located.

We only recognize the Roman occupation by the bricks, the shards of

pottery, the little terracotta and bronze deities that we still find

there: we only recognize that of the Arabs by the garbage with which it

covered the ground, and which usually form the ruins of their

buildings. All those of later times have barely left traces of their

existence; everything has perished in front of these Egyptian

monuments, dedicated to posterity, and which have resisted men and

times.

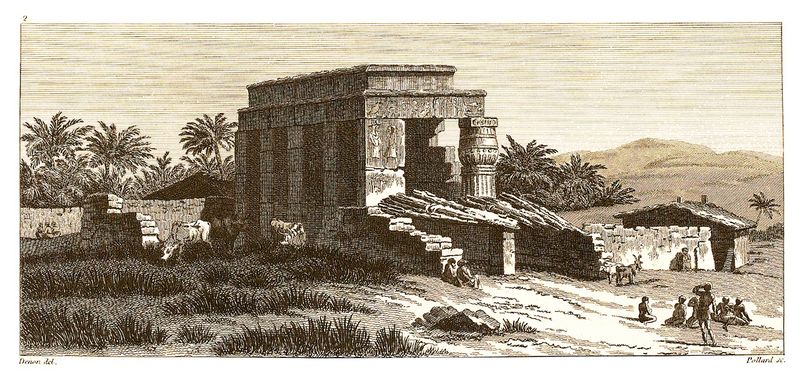

In the middle of the vast field of bricks and terracotta,

of which I have just spoken, still stands a very ancient square temple (plate 30-2),

surrounded by a gallery of pilasters, with two columns in the portico;

only two pilasters are missing at the left corner of this ruin: other

buildings had been added later, of which only a few fragments remain,

which cannot indicate anything about the shape they had, but only

attest that the accessories were larger than the sanctuary; the latter

is covered on the outside and in with hieroglyphics in fairly well

preserved and very well sculpted reliefs: I drew a whole side of the

interior part; the one facing him is almost only a repetition. This

type of painting is (p.297) so much more interesting to offer for

discussion, as it has a unity that I had not yet encountered in these

kinds of decorations, usually divided into compartments: j I also

designed a whole side of the exterior, and a single pilaster; all the

others more or less resemble it: the picturesque view of the entirety

of this small building will give an idea of its importance and the

state of its conservation.

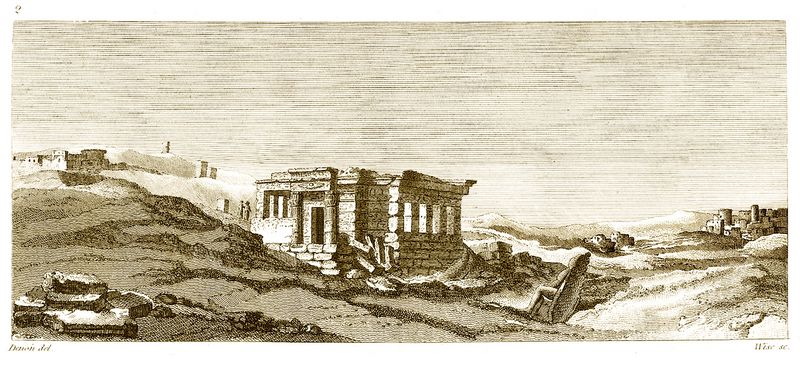

"No.

2.—Ruins of one of the temples of Elephantine. This monument is of

great interest for its fame, for its conservation, for the beauty of

its interior sculptures; it occupied the center of Elephantine Island,

dedicated to wisdom under the name of Cneph; preserved almost entirely

in the middle of the rubble of the monuments by which it was

surrounded, it has only one corner of its gallery damaged: the two

parallel fragments that can be seen behind are two jambs of a granite

door; the statue in the second plane is that of a god, a priest or an

initiate; it is too crude to distinguish its attributes; it is made of

granite and 10 feet in proportion: the stones in front are the rubble

of a building whose substructions will join the fabric of the temple,

and depended on it according to all appearance: a hundred toises in

front of this view, and even on the edge of the Nile, the entire space,

is covered with the debris of degraded and almost shapeless

structures." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Was this the temple of Cneph, the

good genius, the Egyptian god, who comes closest to our ideas of the

Supreme Being? or was this temple, cited by historians, the one seen

six hundred steps further north, which is more ruined, of the same

shape, of the same size, and of which all the ornaments are accompanied

by the serpent, emblem of wisdom and eternity, and particularly of the

god Cneph. Judging by all that I have seen of Egyptian buildings, the

latter is of the order most anciently used, it is absolutely of the

type of the temple of Kournou in Thebes, the one which seemed to me the

oldest of this city. What I found particular about the sculpture of

this temple is more movement in the figures, longer and more composed

dresses: the three figures of this last bas-relief seem to thank a hero

of having delivered them from a fifth character who was almost erased,

but who we recognize as having been overthrown. Is this sculpture,

where it seems that there is a kind of grouped composition, with

perspective, earlier or later than that where the Egyptians had

established a rhythm for their figures, in order to make them, like

writing, characters, the meaning of which we recognized at first sight,

which we explained without almost needing to look at them? There is

only one column of the portico preserved from this last building, and

one whole side of the gallery in pilasters; the rest is absolutely

destroyed.

Plate 37-2: Temple on Elephantine Island.

"No.

2.—View of the ruin of a temple on Elephantine Island, taken from the

south-east corner, from where we see the portion of gallery which

surrounded the temple." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

(p.208) In the middle of the island, there are two

jambs of a large exterior door, made of granite blocks, decorated with

hieroglyphs: this debris undoubtedly belonged to some monuments of

great magnificence, some of which A weak excavation could reveal the

extent. To the east is another fragment of a very small and very neat

building; what we see of it is the western side of a narrow chamber or

a very small temple, and what remains of the hieroglyphics is perfectly

carved; the ornaments are overloaded with the lotus, and among others

with the flowers of this plant, whose leaning stem seems to be revived

by a figure who waters it as in the painting I found at Lolopolis. This

chamber or temple consisted of a narrower corridor, which, judging by a

series of factories, led to a gallery opening onto the Nile, and

resting on a large covering which protected the eastern part of the

island from being degraded. by the swirl of the river's current: there

are still three porticos of this gallery, and a granite staircase which

goes down to the river; Would this gallery, this decorated room, and

this staircase not be this observatory and this nilometer that

travelers seek in vain in Syene? Concerned by this idea, I looked

carefully and could not discover any mark on the covering of the

staircase which indicated any graduation; but for the rest the very

steps of the staircase could have been used, and the upper part of this

staircase being cluttered, it is possible that the measurements were

marked in this part which I was not able to see [1].

All these

structures stand on masses of rocks, covered with hieroglyphs engraved

with more or less care. Further on, advancing towards the north, we

find two portions of parapet, which leave between them an (p.209)

opening to descend to the river: on the interior right flank is a

marble bas-relief, representing the figure of the Nile, four feet in

proportion, in the attitude of a colossus which is in Rome, and which

represents this same river. This copy of the same idea proves at the

same time that the building is Roman, that it is later than the time

when this Greek masterpiece was brought to Rome, and that the Romans in

their establishment at Syene, having able to add luxury and superfluous

ornaments to the constructions of basic necessity, there had been more

than a military station, but a powerful colony: the baths and precious

bronze utensils that are still found there daily provide support of

this opinion on the wealth and duration of this colony.

The

island of Elephantine, defended to the south by breakers, was

undoubtedly greatly increased to the north by alluvium; these alluviums

daily become plowed land and quite pleasant gardens, which, perpetually

watered by rosary wheels, produce four or five harvests per year; also

the inhabitants are numerous, well-off, and very friendly. I called

them from the other side; they came to get me with their boats; I was

soon accompanied by all the children, who brought me and sold me

fragments of antiquity, and raw carnelians: with a few crowns, I made

many little ones happy, and their parents became my friends; they

invited me, prepared me for lunch in the temples where I was to come

and draw; finally I was like the benevolent owner of a garden, where

everything that we seek elsewhere to imitate was there in reality,

islets, rocks, desert, fields, meadows, gardens, bocage, hamlets, dark

woods, extraordinary plants and varied, river, canals and mills,

sublime ruins: a place all the more enchanted because, like the gardens

of Armida, it was surrounded by the horrors of nature, those of the

Thebaļs finally, whose contrast made one feel happiness . The senses,

and (p.210) imagination also in activity, I have never spent more hours

delightfully busy than those I gave on my solitary walks in

Elephantine: this island alone is worth the entire territory of

mainland which borders the city.

The population of Syene is

large; trade, however, is reduced to senna and dates, and these two

articles paid for all the other needs of the inhabitants, the

maintenance of a kiachef, a governor, and a Turkish garrison: the senna

which grows around Syene is mediocre; we only sell it by fraudulently

mixing it with that of the desert that the Barabra bring, and that they

sell for about a hundredth part of what we pay for it in Europe; it is

true that a number of duties are imposed before arriving there, and

that it is one of the most important articles of the customs of Cairo

and Alexandria. The second item of export is that of dates; They are

dry and small, but so abundant that, in addition to being the main food

of the inhabitants, boats loaded with them arrive every day in Lower

Egypt.

Chapter 43: Cavalry Combat against the Mamluks. (p.210)

We

learned from our spies that the Mamluks were going back as far as

possible beyond the cataracts, that they were ravaging the two banks of

the Nile which still provided them with some fodder. They had brought

provisions of flour and dates from Deir and Bribes; but the aga who

resides there told them that this help would dry up. They occupied ten

leagues of space on both banks; their rear guard was only four leagues

from us, from where they knew everything we did, (p.211) as we were

informed of all their movements by the same means, and perhaps by the

same emissaries, who faithfully served both parties with the same

exactitude.

General Daoust had encountered Assan-bey on the

right bank, opposite Edfu, at the moment when he was approaching the

Nile to draw water: the eminent danger of losing his crews made him

charge with fury ; the eagerness of our people to seize it, and a

little contempt that they had taken at the battle of Samanhout, made

them attack with too much negligence. This combat of two hundred

horsemen against two hundred horsemen was rather a melee than a battle;

both parties demonstrated incredible valor. The charge lasted half an

hour: the battlefield remained with the French; but Assan-bey obtained

what he had wanted, which was to save his crews: there remained thirty

to forty dead on our side and as many wounded; there were twelve

Mamluks killed and many wounded: Assan was injured in the leg: so that

no one had to applaud this encounter.

Chapter 44: Careers. (p.211)

We

went in search of the boats that the Mamluks had tried to sail up: our

plan was at the same time to see the cataracts; through the granite

rocks we came across the quarries from which the blocks were detached

which were used to make these colossal statues which have been the

object of admiration for so many centuries, and whose ruins still

strike us astonishment; it seems that the intention was to illustrate

the masses which produced them, by leaving hieroglyphic inscriptions on

the spot which perhaps commemorate them. The operation by which we

(p.212) detached these blocks had to be the same as that which is used

today, that is to say, that we prepared a crack, and that we burst the

mass by a series of wedges struck all at once.

The edges of

these first operations are preserved so vividly in this unalterable

material that it still seems as if the work was only suspended

yesterday. I made a drawing of it. The quality of this granite is so

hard and so compact that the rocks found in the current, instead of

deteriorating by decomposing, have acquired luster by the friction of

the water. The most beautiful granite, the most abundant, is pink

granite; the gray is often too micaceous: between these blocks we find

veins of very shiny quartz, layers of a red stone which reflects the

nature and hardness of porphyries, and other beds of this black and

hard stone, which we have long taken for basalt, and which the

Egyptians often used for their medium-sized statues.

Footnotes:

1.

[Author's footnote:] Strabo, who had observed Syene carefully, and who

described it in detail, said that this nilometer was a well which

received the waters of the Nile, and that the marks according to which

the flood were engraved on the sides of this well.

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|