| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Voyage in Lower and Upper Egypt, during the Campaigns of General Bonaparte. Vivant Denon | | | | |

|

Chapter 45: Cataracts. - Island and Monuments of Philae. (p.212)

A

league and a half beyond the quarries the rocks multiply, and form a

bar, where we found the boats of the Mamluks fixed between the rocks

until the first flood of the river; the surrounding peasants had taken

the equipment and provisions. There we left the small boat in which we

had come, and, going back on foot for a quarter of an hour, we saw what

we agree to call the cataract. It is only a break of the river which

flows through the rocks, forming in some places waterfalls a few inches

high; they are so insignificant that we could barely express them in a

drawing: I (p.213) made only two of the bar where the navigation ends,

in order to destroy the idea we had of the fall of these famous

cataracts; Besides, they would make a beautiful picture if painted with

the color that characterizes them.

These

mountains, all bristling with black and sharp asperities, are reflected

in a dark manner in the mirror of the waters of the river, constrained

and narrowed by a number of granite points which divide it by tearing

its surface, and crisscross it with long white traces; these austere

shapes and colors are contrasted by the tender green of the groups of

palm trees thrown here and there across the rocks and the azure vault

of the most beautiful sky in the world: this well-done painting would

have the singular advantage of offering everything at once the image of

a true and completely new nature. When we have passed the cataracts,

the rocks rise, and at their summits blocks of granite pile up, which

seem to pyramid and balance themselves to produce picturesque effects.

It is through this harsh and austere nature that we suddenly discover

the superb monuments of the island of Philae, which form a brilliant

contrast and one of the most wonderful surprises that a traveler can

experience.

The Nile makes a detour as if to come and seek out

and enclose this enchanted island, where the monuments are separated

only by a few clumps of palm trees, or rocks, which only seem preserved

to group the riches of nature with the magnificence of the art, and

make a bundle of all the most picturesque and most imposing things they

can muster. The enthusiasm that the traveler feels at any moment at the

sight of the monuments of Upper Egypt may appear to the reader as a

perpetual emphasis, a monotonous exaggeration, and is, however, only

the naive expression of the feeling imposed by the sublimity of their

character; it is the distrust that I have of the insufficiency of my

drawings to give the idea of this great character, which means that I

seek, by my (p.214) expressions, to restore to these edifices the

degree of surprise that they inspire, and that of admiration which is

due to them.

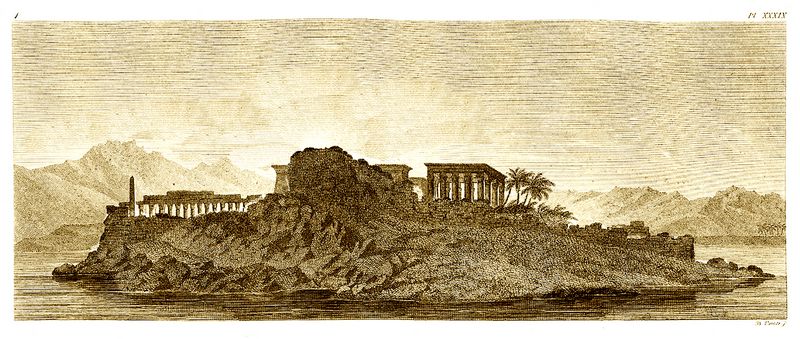

"No.

1.—View of the island of Philae; equally picturesque in all aspects: I

thought I could not repeat the image too often; this is taken from the

east to the west of the setting sun, as I first saw it; the rocks which

are on the right, and which look like ruins, are other islands: in the

small plain which is below, we still find monuments: it is necessary,

for the understanding of the localities, to consult the map, Plate 38,

and its explanation." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

There

were no inhabitants on the mainland, they had even left Philae, and had

retired to a second, larger island, where they made savage cries, which

we were assured were cries. of fear; we did what we could to persuade

them to send us a boat which was on board; we couldn't get anything

from it. Moreover, as this branch of the Nile is narrow, this did not

prevent me from taking views of the island under the three aspects that

it could offer us. We returned very happy with our day; but this

overview did not seem sufficient to me for such important antiquity

objects, for such important monuments, so well preserved, and whose

details should be so interesting.

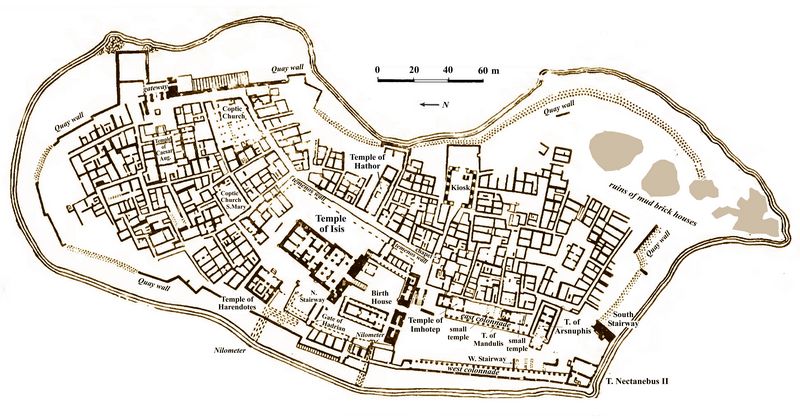

Fig.1: Map of Philae, showing Bigeh Island at left [from Volume I of Description de l'Egypte [1] (ed. Jomard), 1809, Plate 8.]

A few days later we learned

that the Mamluks from the right bank were coming to forage up to two

leagues from us; we set about repelling them; we left with four hundred

men, and we advanced on Philea by the land road through the desert:

what is particular about this road is that we see that it was traced,

raised as a causeway, and very practiced in the past.; this space was

the only one in Egypt where a major road was absolutely necessary; the

Nile ceasing to be passable because of the cataracts, all the

merchandise from Ethiopia's trade which came to land at Philea, had to

be transported by land to Syene, where they were embarked again. All

the blocks encountered on this road are covered with hieroglyphics, and

seemed to be there to entertain passengers. I made drawings of several

of these rocks; a stranger one has the shape of a seat which was

finished by making a staircase in the solid mass to reach the stride

(p.215) of the armchair; all covered with hieroglyphics, most of which

are very careful; I made the drawing of this block, and that of the

inscription.

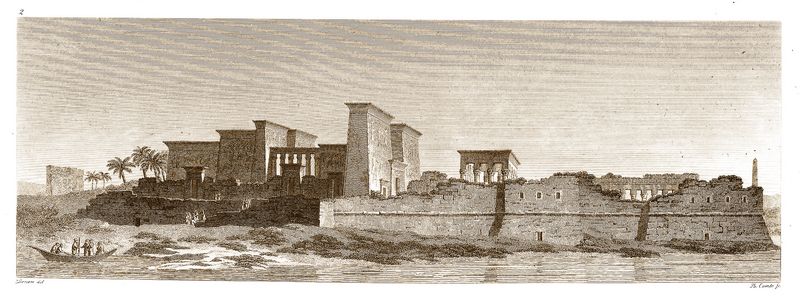

"No.

2.—Another view of Philae at the moment when the inhabitants, naked,

and holding in their hands large sabers, long pikes, guns and shields,

mounted on the top of the rock, declare war on us: this painting was as

beautiful by the colors, by the forms of nature, as by the monuments

and the groups of inhabitants who visited them." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Another particularity of this road are the ruins

of lines built of earthen bricks baked in the sun, the base of which is

fifteen to twenty feet thick: this entrenchment ran along the valley

bordering the road, and led to rocks and to forts nearly three leagues

from Syene. Although these walls were built of less precious materials,

they were manufactured at an expense which attests to the importance

that was placed on the defense of this point: could these be the

remains of the famous wall built by a queen of Egypt called Zuleikha,

daughter of Ziba, one of the Pharaohs, and which extended from ancient

Syene to where El-Arych is now, and whose fragments the Arabs call

Haļf-źladjouz, or the wall of Old ?

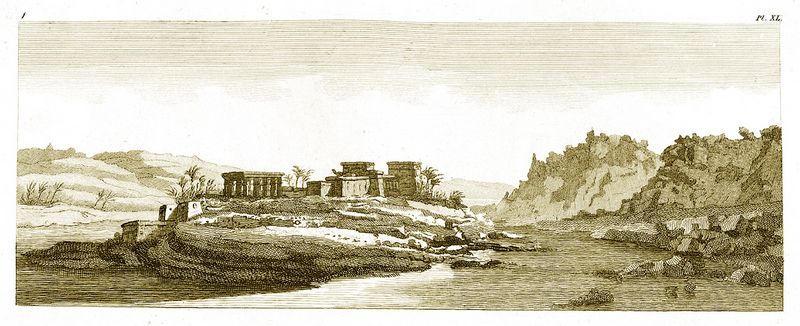

Plate 40-2: View of Philae facing north side (Denon 1802 vol.3, plate 40).

"No.

2.—Northern part of the island of Philae, with the development of all

its monuments (See the Map, Plate 38, and its explanation): one may be

surprised to find on the border of Ethiopia [3] a large number of

monuments of this magnificence, so well preserved after so many

centuries." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

We

found the inhabitants of Philae returned to their dwellings, but

determined not to receive us; we again attributed this ill will to the

fear we caused them, and we continued our journey: beyond Philea the

river is absolutely free and navigable; after passing an Arab fort and

a mosque from the same time, the shore of the Nile gradually becomes

impassable; instead of this profusion of monuments and inscriptions, we

saw only poor nature, left to itself, and on the rocks a few dwellings

which looked like savages' huts; we entered a desert cutting an angle

of the Nile to shorten the path; and after having climbed and descended

for several hours valleys as hollow as if we had been in a region

subject to storms and torrents, we emerged on the Nile by a ravine

which brought us to Taudi, a poor village on the bank of the river; As

we approached, the Mamluks had just abandoned this village, leaving

their dishes, their pots, and even the soup that they had (p.216)

prepared, and which they were to eat as soon as the sun set; because it

was the month of Ramadan, a kind of Lent, during which the Muslims,

even the soldiers, do not eat as long as the sun is on the horizon.

"No.

1.—View of Philae, from west to east at sunrise; This island is so

picturesque that I tried to present it in all its aspects and at all

times of the day." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Chapter 46: The Gonblīs. (p.216)

We

sent a spy during the night; We learned at daybreak that at Demiet,

four leagues higher than Taudi, the Mamluks still finding themselves

too close to us, after having refreshed their horses, had left at

midnight. Our hut to keep them away being full, we took the road to

Syene. I had already had enough of Ethiopia, of the Goublis, and their

wives, whose extreme ugliness can only be compared to the atrocious

jealousy of their husbands: I saw some of them; as I inspired less fear

in the husbands than the soldiers, they placed a certain number of them

under my protection in a cabin, in front of the door of which I had

established myself to spend the night. Surprised by our circuitous

march, at nightfall, they did not have time to flee and hide in the

rocks, or to swim across the river: they absolutely had the fierce

stupidity of savages.

A harsh soil, fatigue, and insufficient

food undoubtedly alter in them all the charms of nature, and even give

to their youth the mark and degradation of decrepitude. It seems that

men are of another species, for their features are delicate, their skin

fine, their countenance lively and spiritual, and their eyes and teeth

admirable. Lively and intelligent, they put so much clarity and

conciseness into their language that a short sentence is always the

complete answer to the question asked of them: their (p.217) character

of liveliness is more analogous to ours than that of other orientals;

they hear and serve quickly, steal even more nimbly, and are greedy for

money, which can only be justified by their excessive poverty, and

compared only to their frugality. It is to all these reasons that their

thinness must be attributed, which is not due to their poor health,

because their color, although black, is full of life and blood, but

their muscles are only tendons: I do not I haven't seen a single fat

one, not even fleshy.

Chapter 47: Capture of the island of Philae. (p.217)

It

was necessary to starve the country to keep the enemy away; we bought

the cattle, we paid for the harvest in grass, the inhabitants

themselves helped us to harvest what it promised them in terms of

provisions, and followed us with what animals they had. Thus taking the

entire population, we left behind us only a desert. On my way back, I

was again struck by the sumptuousness of the buildings of Philea; I am

convinced that it was to produce this effect that the Egyptians had

brought this splendor of monuments to their border. Philae was the

warehouse of an exchange trade between Ethiopia and Egypt; and wanting

to give the Ethiopians a great idea of their means and their

magnificence, the Egyptians had raised a number of sumptuous buildings

to the confines of their empire, to their natural border, which was

Syene and the cataracts.

We had another talk with the

inhabitants of the island; it was more explanatory: they told us that

for two months in a row we would come every day without us ever being

allowed to reach them. This time again we had to take it for granted,

because we had no means (p.218) to change their decision: but as it

would have been a bad example for a handful of peasants to be insolent

four steps from our establishments, we put off making observations to

them until the next day that could change something in their

determination. We actually returned there with two hundred men; they

did not see them before they put themselves in a state of war: it was

declared in the manner of savages, with cries repeated by the women.

The inhabitants of the neighboring island came running with weapons

which they flashed like wrestlers; there were some completely naked

holding a large saber in one hand, a shield in the other, others with

matchlocks and long pikes; in a moment the entire eastern rock was

covered with groups of enemies.

We shouted to them again that we

had not come to harm them, that we were only asking them to enter the

island in a friendly manner: they replied that they would never give us

the means to do so, that their boats would not come. to look for us,

and that finally they were not Mamluks to retreat before us: this

boasting was covered by cries of unanimity which resounded from all

sides: they wanted to fight; they had defended themselves against the

Mamluks; they had beaten their neighbors; they wanted to have the glory

of resisting us, and even of braving us. Immediately the order was

given to our sappers to tear down the roofs of the huts on dry land

which could provide us with wood to make a raft: this act was the

declaration of war: they fired on us; posted and hidden in the cracks

of the rocks, they covered us with very well adjusted bullets. At this

moment a piece of cannon arrived, the very sight of which carried their

rage to the last degree; from then on there was no more communication

between the great island and the island of Philea; those of the great

one took their flocks, made them cross the arm of the river, and went

to lose them in the desert.

We noticed that the palm wood was

too heavy and was taking on water, (p.219) the descent had to be

postponed until the next day: the troop remained; everything needed to

make a raft big enough to carry forty soldiers was brought in. This

work occupied the whole of the next day; this delay increased the

insolence of these unfortunate people, who dared to propose to the

general to pay a hundred piastres to pass alone and unarmed on the

island: but the scene changed when suddenly they saw the large island

flooded with our volunteers whose descent had been protected by grape

cannon; terror followed, as usual, insufficient audacity; men, women,

children, everyone threw themselves into the river to swim away;

retaining the character of ferocity, mothers were seen drowning the

children they could not take away, and mutilating girls to protect them

from the violence of the victors. When I entered the island the next

day, I found a little girl of seven or eight years old, to whom a

sewing done with as much brutality as cruelty had deprived her of all

the means of satisfying her most pressing need, and caused her serious

problems. horrible convulsions: it was only with a counter-operation

and a bath that I saved the life of this unfortunate little creature

who was quite pretty. Others, of a more advanced age, were less austere

and chose their own winners.

Finally this island colony found itself dispersed in a few moments,

having

caused, relative to his means, an immense and irreparable loss. They

had plundered the boats that the Mamluks had not been able to bring up,

and had made stores of this booty, which, in comparison with their

neighbors, made them of unexampled wealth, and were able to ensure

their ease and their rest. for number of years; In a few hours they

found themselves deprived of the present and the future, they went from

ease to need, and were obliged to seek asylum from those among whom

they had brought war a few days previously. The evacuation (p.220) of

the stores located on the large island occupied the soldiers for the

rest of the day; and I used this time to make drawings of the rocks and

the antiquities found there.

Chapter 48: Description of the Ruins of Philae. (p.220),

These

ruins consist of a small sanctuary, preceded by a portico of four

columns with very elegant capitals, to which another portico was later

added which was undoubtedly due to the circumvaliation of the temple.

The oldest part, worked with more care, was much more decorated; the

use made of it by Catholicity has distorted its character, by adding

arches to the square shapes of the doors. In the sanctuary, right next

to the figures of Isis and Osiris, we can still see the miraculous

impression of the feet of S. Anthony or of S. Paul, a hermit.

The

next day was the best day of my trip: I was in possession of seven to

eight monuments in the space of three hundred toises, and above all I

did not have at my side any of these curious impatient people who

always believe they have enough seen, and who relentlessly urge you to

move on to something else; no drums beating the gathering or departure,

no Arabs, no peasants; alone at last, and enjoying my ease, I began to

make the map of the island and the plan of the buildings with which it

is covered. I was on my sixth trip to Philae; I had used the first five

to take the views of the outside and surrounding areas.

This

time, which was the first time I touched the ground of the island, I

began first by exploring its entire interior, to become acquainted with

its various monuments, and to form a general idea of it, one (p .221)

kind of topographic map, containing the island, the course of the

river, and adjacent features. I was able to convince myself that this

group of monuments had been built at different times, by various

nations, and had belonged to various cults, finally that the union of

these buildings, each of which was regular, offered an irregular

ensemble as magnificent as it was picturesque. I distinguished eight

sanctuaries at the particular temple, more or less large; built at

different times, one had been respected in the construction of the

other, which had harmed the regularity of the whole.

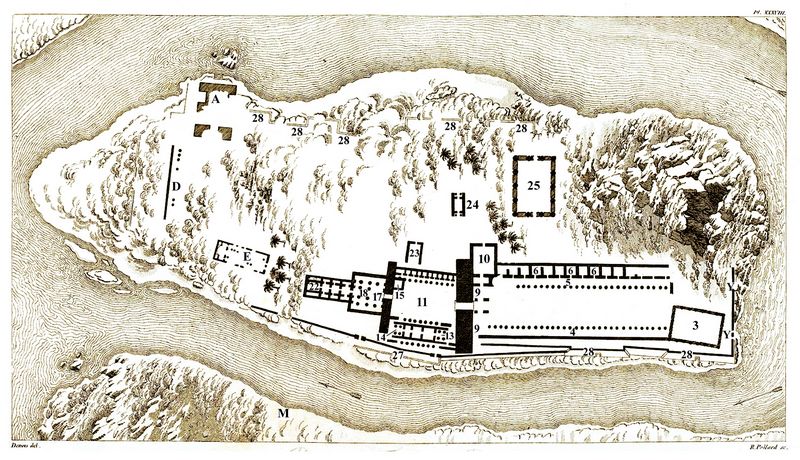

"Plan

of the island of Philae, located beyond the cataracts of the Nile, at a

bend in the river, lying in its length from northwest to southeast; it

is approximately 800 toises long and 120 wide; it is almost entirely

covered with the most sumptuous monuments from various centuries; the

southwest of its upper part is occupied by a beautiful, very

picturesque rock, whose harsh and wild appearance seems to add to its

magnificence, and to highlight the beautiful regular lines of the

architecture of the temples which surround it. The current of the

river, hitting up to the foot of the rock, letter &, dispensed with

making a quay in this part: at the moment when the rock was missing, a

lined quay began, about 86 feet high, decorated with a torus, above

which rises a parapet at support height; on this parapet rise two small

sandstone obelisks, without hieroglyphics, and of mediocre workmanship;

there is only one left standing."

"The quay continues on an

embankment, in the northern part of the island, with posterns (No. 28)

which open and embark on the river: this was through which the

inhabitants passed when they fled, and abandoned the island to us (See

the Journal, page 217): No. 27 is a ramp which led from the river to a

gate; the wall continued as far as another door, where it resumes and

is lost in ruins; this is all that remains of the Egyptian

circumvallation. The two doors are beautiful and well preserved."

No.

3 is a peripteral temple [3]; the columns engaged up to a third, the goblet

capitals surmounted by a head of Isis (See Plate XLIV, No. 1), carrying

an architrave and a cornice without cover, and closing with two doors

without bedsteads. No. 4, a gallery 250 feet long [4]; this gallery was

made up of fairly well carved columns, with flared capitals, surmounted

by a thimble, an architrave, and a groove; there are differences in

almost all the capitals: this part of the building was less old than

the temple, but more than that which is parallel to it, No. 5, and

which, I believe, was never completed build, although it is more in

ruins than the first; they served as a corridor for a number of cells,

No. 6, which we can believe to have been priests' rooms. No. 10 are two

rooms forming a separate building, a sanctuary of the oldest, and

undoubtedly revered, because it seems that it was to spare its

existence that all the lines of the general plan were distorted; the

sculptures are in preciously carved bas-reliefs."

"No. 9 are two large embankment piers, each 47 feet wide and 22 feet thick, which flank a large and magnificent gate."

"They

are bordered at the corners by a torus, and surmounted by a groove; the

panels, covered with two rows of gigantic hieroglyphs, representing

five great deities; at the bottom, large figures, holding a raised ax

in one hand, and in the other the hair of a group of thirty kneeling

figures imploring their clemency; on the reverse of this building four

figures of priests, carrying a boat, in which is an emblem similar to

that which is in the boat of the bas-relief of the temple of

Elephantine; on both sides of the door there were two small granite

obelisks, 18 feet high, covered with very purely carved hieroglyphics,

and in front were two sphinxes 7 feet in proportion; all this is

reversed. No. 11 [5] is another courtyard, 80 feet by 45, flanked by two

columnar galleries, behind which on the right is a series of cells 10

feet deep, and on the left a particular building, composed of two

porticos (No. . 13 and 14), and three rooms of various sizes,

communicating with each other, and opening onto the porticos: it is the

only one I have seen of this kind; if it were more lit, one could

believe: that it would have been a main apartment; its execution is

very careful, and its effect very picturesque."

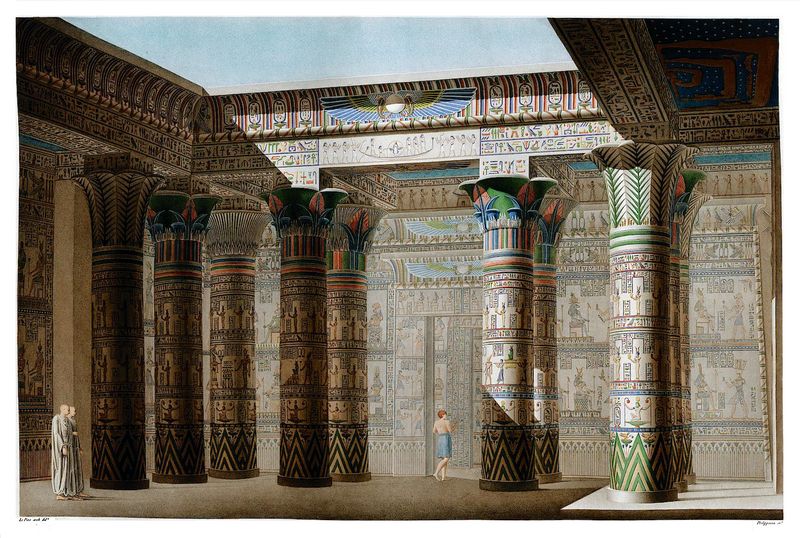

"No. 15 is

another sanctuary, smaller than all the others, leaning against two

other embankment piers, a third smaller than the first, and serving as

a portal to the largest and most regular building of all. this group:

the piece that follows, No. 17 and No. 18, is a kind of. portico, [6]

decorated with ten columns and eight pilasters 4 feet in diameter, as

magnificent as it is elegant; the columns and walls covered in

hieroglyphic paintings, sculpted in the massif, perfected in stucco,

and painted; the portico and two returns covered in flowerbed ceilings,

sculpted and painted in an astronomical picture, or in an azure

background with white stars. The part numbered 17 is open to the sky,

which produces a beautiful daylight, and one of the most beautiful

architectural effects: an exact painting made with natural colors would

be as imposing and as pleasant as it would be new and curious; the

relief of the architecture and the sculpture giving shadows to the flat

tones of the painting, here completing the rotation; it took on a

harmony and a magnificence which amazed me: I could not tear myself

away from this superb and astonishing piece, of which I would have to

draw all the details, I only had time to take the plan. (See Journal,

page 221.)"

"This open portico succeeded the closed part of the

temple, 60 feet deep by 30 feet wide, divided along its length into

four rooms communicating by four doors diminishing in opening; the

first of 7-4, the second of 6-4, the third of 5-6, the fourth of 4-8; a

glance at the plan gives a clearer idea than a description, where the

repetition of the same expressions rather distracts the attention than

enlightens the imagination: it would be very difficult to assign the

use of these various rooms, of which there are some so long, so high,

so narrow, so decorated, and so obscure; in the back room is still an

altar or an inverted pedestal, and at the right corner, No. 22, is a

kind of tabernacle or monolite temple, bearing as decoration the door

of a temple 7 feet high by 3 feet wide, and 2 feet 8 inches deep, of a

single granite stone: we can still see in the stone the hollow where

the hinges of the door were sealed, which was 3 feet high by 1 foot 6

inches wide ; in the side room, on the right, there was the same

monument in the same material, of which I made a separate drawing, No.

I, Plate XLI."

"These tabernacles were undoubtedly intended

either to contain what was most precious in the temples, such as sacred

things, gold, or precious stones, or perhaps God himself; in this case

it could only be a reptile or a bird, and the door would have been a

grate, to allow air to the animal, if it were alive. I have since

found, on a mummy swaddle, which was from time immemorial in the

library of the French Academy, and which has since passed to that of

the Institute, the representation of one of these small temples, with a

grilled and closed door, and another with the door open, a bird in the

temple, and a man who brings it food, and a third, where the guardian

of the birds watches them while they take the air. This discovery seems

to me to leave no doubt about the use of these monolite sanctuaries."

"After

this series of buildings the most considerable monument is a long

square portico, No. 25, [7] 64 feet long by 44 wide; four columns in

front, and five on the side; two 9-foot doors without box springs; this

building, open to the sky, was only enclosed by a base, which only

reached half the height of the column; this monument, undoubtedly

erected in the last moments of Egyptian power, was never finished; but

what exists attests that Part had then reached its last degree of

perfection: the capitals are the most beautiful, the most ingeniously

composed, and the best executed of all those I have seen in Egypt; the

lotus is intertwined with infinite grace with the volutes of the Ionic

and Composite capital; there are only two base panels that have been

completed. The lotus was the ornament that reigned everywhere in this

building."

"No. 23 is still a sanctuary, very difficult to

separate from its own rubble and that of other buildings. No. 24 is a

small sanctuary of perfect conservation; the nobility of its

proportions Illusions the smallness of its dimensions; it consists of a

portico decorated with two columns, and a sanctuary 11 feet 6 inches

deep by 8 feet wide; the ornaments are very finished and of exquisite

taste; it is a real temple to antes, amphiprostyle. (See its Frieze,

Plate LVI. No.2).

"No. 28 are bastioned parapets, which can

make one believe that this entire island was surrounded by walls: it is

however possible that it is of Roman construction, as is certainly the

factory to which they lead, letter A, which served as a port or arrival

point; the vaults and the Doric style of these ruins leave no doubt

that these are no longer Egyptian constructions: could this be a Roman

customs house? a stepped ramp, and a small reef opposite make it still

a small harbor for boats."

"The letter D is a wall, decorated

with Doric pilasters, opposite which the bases of columns announce that

there was a covered gallery, and behind the wall other ruined

buildings."

"The monument of the letter E is the ruin of the

Greek church, with its nave and the closed choir; it had been built of

ancient materials, to the sculptures of which crosses, foliage, and

other ornaments in the style of the time had been added."

"The

rest of the island offers only a few small crops grown in the land,

gathered by the alluvium of the river; and a few plantations of trees,

which blend admirably well with the rocks, the monuments, the river,

and beautiful depths, offer at every moment the most varied and

interesting pictures." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Part of the

increases had only been made to connect what had been built previously,

saving as skillfully as possible false squares and general

irregularities. This kind of confusion of architectural lines, which

appear errors in the plan, produces picturesque effects in the

elevation that geometric straightness cannot have, multiplies the

objects, forms groups, and offers the eye more richness than cold

symmetry. There I was able to convince myself of what I had already

noticed at Tentira and at Thebes, that the system of construction was

to raise masses, in which one. worked for centuries on the details of

decoration, starting with architectural lines, then moving on to the

sculpture of hieroglyphic figures, and finally to stucco and painting.

All these different periods in the works are very sensitive here, where

there is nothing finished except what is of the highest antiquity; part

of the constructions which served to connect the various monuments had

neither been smoothed out, nor sculpted, nor even completed; the large

and magnificent long square monument is of this number: it would be

difficult to assign a use to this building, if the details of the

ornaments representing offerings did not indicate that it must still

have been a temple.

However, it has neither the shape of a

portico nor that of a sanctuary; the columns which make up its

perimeter, and which are only engaged (p.222) up to half their height,

carry only an entablature and a cornice without a roof or platform; it

was only opened by two doors without simes which crossed its length.

Raised undoubtedly in the last era of Egyptian power, art is manifested

there in its ultimate purity; the capitals are of admirable beauty and

execution, the volutes and leaves, excavated as in the good times of

Greece, symmetrically diversified as at Apollinopolis, that is to say,

varied among themselves and similar in their correspondents, and all

subject to the same parallel.

Fig.3: Reconstruction of the portico of the Temple

of Isis on Philae, by La Pere, an architect with the French expedition

(published as Plate 18 in Description de l'Egypte, vol. 1, 1809.)

I had no little difficulty in

clearing out in my imagination these long galleries cluttered with

ruins, in following the lines of the quays, in raising the sphinxes and

obelisks, in connecting the communications of the ramps and staircases:

attracted by the paintings, by the sculptures, I was assailed at the

same time by all kinds of curiosity, and, in fear of sharing my errors

with those to whom I intended to give an account of my sensations and

my operations, I would have liked to be able to trace on my plan the

state of the ruins and the mixture of rubble, and on this plan

communicate to them my doubts and my uncertainties, and discuss them

with them. What could this large number of sanctuaries so close

together and so distinct mean? Were they dedicated to different

deities? Were they votive chapels, or places of station for cult

ceremonies? The most secret sanctuaries contained even more mysterious

sanctuaries, monolite temples, which were tabernacles which contained

what was most precious, what was most sacred, and perhaps even the

sacred bird which represented the god of the temple, the hawk, for

example, which was the emblem of the sun, to which precisely this

temple was dedicated.

Under the same portico were painted on the

ceilings astronomical paintings, theories of the elements, and on the

walls, religious ceremonies, (p.223) images of priests and gods; next

to the doors, the gigantic portraits of some sovereigns, or emblematic

figures of strength and power threatening a group of suppliant figures,

whom they hold with one hand by their gathered hair. Are these

rebellious subjects? are they defeated enemies? I would lean towards

the latter opinion, because the figures representing Egyptians never

have long hair. Besides this large enclosure, where this number of

temples was attached and grouped by the priests' lodgings, there were

two isolated temples; the large one, of which I have already spoken,

and a second, the prettiest that one can imagine, perfectly preserved,

and of a size so small that it makes you want to take it away. I found

inside the remains of a household, which seemed to me to be that of

Joseph and Mary, and brought to my mind the picture of a flight into

Egypt in the truest and most interesting style. If we ever wanted to

transport a temple from Africa to Europe, we would have to choose this

one, apart from the fact that it offers all the possibilities through

the smallness of its size, it would give a palpable testimony to the

noble simplicity of the architecture. Egyptian, and would become a

striking example that the character and not the extent makes the

majesty of a building.

In addition to the Egyptian monuments,

there are Greek or Roman ruins to the south-east of the island, which

appeared to me to be the remains of a small port, and a customs house,

the facade wall of which is decorated with Doric pilasters and arcades;

a few torn columns formed in front of an open gallery, a kind of

portico: between these ruins and the Egyptian monuments, we can notice

the base of a Catholic church, built of ancient fragments, mixed with

crosses and early Greek ornaments; for humble catholicity seems never

to have been opulent enough in these countries to completely separate

its cult from the splendor of idolatrous temples. After having

established its saints through the Egyptian divinities (p.224), it

often paints S. John or S. Paul next to the goddess Isis, and disguises

Osiris as S. Athanasius; When she left the temples, she degraded them,

taking the ready-made stones to build her churches.

So many

objects to question! and time passed; I would have liked to hold back

the sun: I had spent many hours observing, I began to draw, to measure:

I saw the end of the removal of the stores, I could no longer hope to

return to Philae: my good people from Elephantine were not here, and

the troops had already been too tired from the siege of this little

island. I left her with my eyes tired of so many objects, and my soul

filled with the memories attached to them; I left at nightfall, loaded

with my loot, and my little daughter, whom I handed over to the sheikh

of Elephantine, who returned her to her parents.

We had planned

to put Syene in a state of defense: the engineer Garbé had chosen to

build a fort a platform on an eminence, to the south of the town, which

commanded all the approaches, and from where we discovered all the

surrounding country. We lacked shovels, picks, hammers and trowels; we

forged everything: we had no wood to make bricks; we brought together

all those from the old Arab factories. Similar to the Roman cohorts who

had already inhabited the same place, the brave twenty-first

experienced no difficulties, or overcame them all. Each individual was

taxed two trips per day for the transport of materials; many had

difficulty carrying themselves, and no one was spared a single trip:

the bastions were laid out, and the work carried out with such

celerity, that in a few days we saw the fortress emerge from its

foundations; at the same time a Roman factory was bastioned and

crenellated, well built and fairly well preserved, which had been a

(p.225) bath, and which, by its location, had the double advantage of

protecting the course of the river.

The end of the French march

to Egypt was inscribed on a granite rock beyond the cataracts. I took

advantage of the opportunity of a reconnaissance which was carried out

in the desert of the left bank, to seek out the quarries of which

Pococke speaks, and an ancient convent of cenobites [8]; after an hour's

walk we discovered this monument in a small valley, surrounded by

decrepit rocks and the sand produced by their decomposition.

The detachment, continuing its route, left me to my research in this place.

The

detachment had barely left when I was terrified at my isolation. Lost

in long corridors, the prolonged sound that my footsteps made under

their sad vaults was perhaps the only one that for several centuries

had disturbed the silence. The monks' cells resembled the animal huts

of a menagerie; a seven-foot square was only lit by a skylight six feet

high: this refinement of austerity, however, only hid from the recluses

the view of a vast expanse of the sky, of an equally vast horizon of

sand, of an immense light as sad and more attenuating as the night, and

which would perhaps have penetrated them even more with the distressing

feeling of their solitude: in this dungeon a layer of brick, a recess

serving as a cupboard were all that art had added to the smoothness of

the four walls: a tower placed next to the door further proves that it

was in isolation that these solitary people took their austere meal.

A

few truncated sentences, written on the walls, alone attest that humans

inhabited these lairs: I thought I saw in these inscriptions their last

feelings, a last communication with the beings who betray their

survival, a hope which time, which erases everything, has given them.

still frustrated. I imagined them dying and wanting to say a few words

that they did not (p.226) have the strength to articulate. Oppressed by

the feeling that this series of melancholy objects inspired in me, I

ran to find space in the courtyard: surrounded by high crenellated

walls, covered paths, and cannon embrasures, everything there announced

that the storms of war had , in this disastrous place, succeeded by the

horror of silence; that this building, taken from the cenobites who had

built it with so much zeal and constancy, had at various times served

as a retreat for defeated parties, or as an advanced post for

victorious parties. The different characters of its construction can

still serve as eras in the history of this monument: begun in the first

centuries of Catholicity, everything that was built by it still retains

grandeur and magnificence; what the war added was done in haste, and is

more ruined than the first constructions.

In the courtyard a

small church built of unfired bricks further attests that a smaller

number of solitaries returned at a later time to reclaim possession;

finally, a more recent devastation suggests that it is only a few

centuries ago that this place was completely given up to the

abandonment and silence to which nature had condemned it [8]. The

detachment which had left me there came to take me back; and it seemed

to me as I was coming out of a tomb. I had drawn a drawing of this sad

place while waiting for the detachment. Regarding the quarries that I

found near there, they were not those where the obelisks were carved;

the obelisks are always made of granite; the granite rocks are far from

this place, and these rocks are sandstone. What remains curious are the

fragments of inclined roads, on which the masses were slid, which were

thus taken to the river to be embarked there and used in the

manufacture of the various buildings.

We learned that the

Mamluks, who had fled before us at Permet, had taken the desert on the

right, and had gone down to join Assan-bey; that Mourat, after lively

discussions, had gathered all that the upper country could provide him

with provisions, and that he was returning through the left desert,

leaving behind him only old Soliman, who held Bribe with eighty Mamluks

. Having nothing more to do in Syene, we left on February 25 [1799]: I would

have happily stayed there for another two weeks; but I would have

feared seeing the burning winds of spring arrive there: I had already

painfully experienced the shock; three days of east wind in January had

inflamed the atmosphere as it is in our heatwave; then followed a north

wind so cold that in four hours it gave me a fever. Hoping to rest, I

got into the boats; they had to march at the same height as the troops

who were returning to the route I had already taken; and I hoped by

that of the river to see Ombos, and the quarries of Gebel Silsilis,

which I had left on the left while going up.

Footnotes:

1. Detailed accounts of Philae and the neighboring sites of Syene and Elephantine Island are given in Description de l'Egypte, a

monumental series of reports and illustrations by members of the

French expedition, published in Paris between 1809-1818. The Description

also covers the sites in Upper and Lower Egypt that Denon first briefly

described. Philae was visited by Jomard and other authors and artists

of the Description

in the September of 1799, about 7 months after Denon was there

with the military expedition pursuing the Mamluks, departing Feb. 25,

1799.

2. The area of

the upper Nile anciently called Nubia, now part of Sudan, was identified in the late 18th century as Ethiopia.

3. The

rectangular structure at area 3 on Denon's plan is now identified as

the Temple of Nectanebus II, the third and last pharaoh of the

Thirtieth Dynasty, reigning from 358 to 340 BC. He was the last native

ruler of Egypt, preceding the Greek-led Ptolemaic dynasty. This

temple is possibly the oldest remaining structure at Philae. (see plan

in fig.2)

4. The long row of columns in area 4 on Denon's plan

is now called the West Colonnade, which was part of a processional area

leading to the Temple of Nectanebus II (see plan in fig.2).

5.

The courtyard of area 11 on Denon's plan is now called the Birth House

or Mammisi, a common feature of Ptolemaic temples. It was erected

beside the temple of Isis during the reigns of Ptolemy II

Philadelphus (284-246 BC) and his son Ptolemy III Euergetes

(246-221 BC), and was dedicated to the young Horus (see plan in

fig.2).

6. Areas 17, 18, and 22 on Denon's

plan are now identified as comprising the Temple of Isis, the main

temple on the island, built during the reign of Ptolemy II (284-246 BC).

This replaced an earlier temple of Isis, thought to have been erected

either by Taharka of the 25th dynasty (690-665 BC) or Psamtik II of the

26th dynasty (595-589 BC) (see plan in fig.2, and reconstruction of portico in fig.3).

7. This structure (Denon's area 25), called the East Temple in the Description de l'Egypte, and now named the Kiosk, is identified as a Roman structure dating from the period of Trajan (AD 98-117) (see plan in fig.2).

8.

Ruins of the monastery of St. Simeon on Syene or Aswan (abandoned in

the 13th c. AD) are located 700 meters from the west bank of the

Nile. It was originally called the monastery of Anba-Hatra, founded by

the anchorite Hatra, who died in the time of Emperor Theodosius I (AD

379-395). Wall paintings found in the rock caves under the brick ruins

are dated to the 6th-7th century.The church ruins visted by Denon were

built in the first half of the 11th century. (For more information, see

Gawdat Gabra. "Coptic Monasteries: Egypt's Monastic Art and

Architecture;" and Monnaret de Villard, 1927.)

.

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|