|

Chapter 10 (part D)

I take this opportunity of giving a

translation of the answer I made to an article published by M. G.

Nikola´des (p.176) in No. 181 of the Greek newspaper ‘?f?Áe???

S???t?se??,’ in which the author endeavours to prove that I am giving

myself unnecessary trouble, and that the site of Troy is not to be

found here, but on the heights of Bunarbashi. [174]

“M.

Nikola´des maintains that the site of Troy cannot be discovered by

means of excavations or other proofs, but solely from the Iliad. He is

right, if he supposes that Ilium is only a picture of Homer’s

imagination, as the City of the Birds was but a fancy of Aristophanes.

If, however, he believes that a Troy actually existed, then his

assertion appears most strange. He thereupon says that Troy was

situated on the heights of Bunarbashi, for that at the foot of them are

the two springs beside which Hector was killed. This is, however, a

great mistake, for the number of springs there is forty, and not two,

which is sufficiently clear from the Turkish name of the district of

the springs, ‘Kirkgi÷s’ (40 eyes or springs). My excavations in 1868,

on the heights of Bunarbashi, which I everywhere opened down to the

primary soil, also suffice to prove that no village, much less a town,

has ever stood there. This is further shown by the shape of the rocks,

sometimes pointed, sometimes steep, and in all cases very irregular. At

the end of the heights, at a distance of 11Ż miles from the Hellespont,

there are, it is true, the ruins of a small town, but its area is so

very insignificant, that it cannot possibly have possessed more than

2000 inhabitants, whereas, according to the indications of the Iliad,

the Homeric Ilium must have had over 50,000. In addition to this, the

small town is four hours distant, and the 40 springs are 3Ż hours

distant, from the Hellespont; and such distances entirely contradict

the statements of the Iliad, according to which the Greeks forced their

way fighting, four times in (p.177) one day, across the land which lay

between the naval camp and the walls of Troy.

“M. Nikola´des’s

map of the Plain of Troy may give rise to errors; for he applies the

name of Simo´s to the river which flows through the south-eastern

portion of the Plain, whereas this river is the Thymbrius, as Mr. Frank

Calvert has proved. In his excavations on the banks of that river, Mr.

Calvert found the ruins of the temple of the Thymbrian Apollo, about

which there cannot be the slightest doubt, owing to the long

inscription which contains the inventory of the temple. Then on the map

of M. Nikola´des I find no indication whatever of the much larger river

Doumbrek-Su, which flows through the north-eastern portion of the Plain

of Troy, and passed close by the ancient town of Ophrynium, near which

was Hector’s tomb and a grove dedicated to him.[175] Throughout all

antiquity, this river was called the Simo´s, as is also proved by

Virgil (Ăn. III. 302, 305). The map of M. Nikola´des equally ignores

the river which flows from south to north through the Plain, the

Kalifatli-Asmak, with its enormously broad bed, which must certainly at

one time have been occupied by the Scamander, and into which the Simo´s

still flows to the north of Ilium. The Scamander has altered its course

several times, as is proved by the three large river-beds between it

and the bed of the Kalifatli-Asmak. But even these three ancient

river-beds are not given in the map of M. Nikola´des.

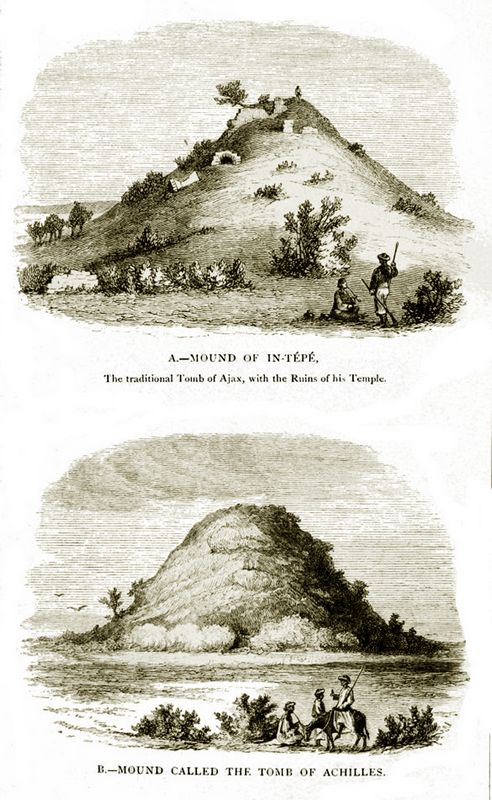

“In

complete opposition to all the traditions of antiquity, the map

recognises the tomb of Achilles in the conical sepulchral mound of

In-TÚpÚ, which stands on a hill at the foot of the promontory of

Rhœteum, and which, from time immemorial, has been regarded as the tomb

of Ajax. During an excavation of this hill, in 1788, an (p.178) arched

passage was found, about 3ż feet high, and built of bricks; as well as

the ruins of a small temple. According to Strabo (XIII. 1. p. 103), the

temple contained the statue of Ajax, which Mark Antony took away and

presented to Cleopatra. Augustus gave it back to the inhabitants of the

town of Rhœteum, which was situated near the tomb. According to

Philostratus (Heroica, I.), the temple, which stood over the grave, was

repaired by the Emperor Hadrian, and according to Pliny (H. N., V. 33),

the town of Aianteum was at one time situated close to the tomb. On the

other hand, throughout antiquity, the tomb of Achilles was believed to

be the sepulchral mound on an elevation at the foot of the promontory

of Sigeum, close to the Hellespont, and its position corresponds

perfectly with Homer’s description.[176]

Plate VI: A (top): Mound of In-Tepe, The traditional Tomb of Ajax, with the Ruins of his Temple.

B (bottom): Mound called the Tomb of Achilles. (p.178)

“The

field situated directly south of this tomb, and which is covered with

fragments of pottery, is doubtless the site of the ancient town of

Achilleum, which, according to Strabo (XIII. 1. p. 110), was built by

the MitylenŠans, who were for many years at war with the Athenians,

while the latter held Sigeum, and which was destroyed simultaneously

with Sigeum by the people of Ilium. Pliny (H. N., V. 33) confirms the

disappearance of Achilleum. The Ilians here brought offerings to the

dead, not only on the tomb of Achilles, but also upon the neighbouring

tombs of Patroclus and Antilochus.[177] Alexander the Great offered

sacrifices{179} here in the temple of Achilles.[178] Caracalla also,

accompanied by his army, offered sacrifices to the manes of Achilles,

and held games around the tomb.[179] Homer never says anything about a

river in the Greek camp, which probably extended along the whole shore

between Cape Sigeum and the Scamander, which at that time occupied the

ancient bed of the Kalifatli-Asmak. But the latter, below the village

of Kumk÷i, is at all events identical with the large bed of the small

stream In-tÚpÚ-Asmak, which flows into the Hellespont near Cape Rhœteum.

“M. Nikola´des further quotes the following lines from the Iliad (II. 811-815):—

?st? d? t?? p??p?????e p????? a?pe?a ??????,

?? ped?? ?p??e??e, pe??d??Á?? ???a ?a? ???a,

??? ?t?? ??d?e? ?at?e?a? ?????s???s??,

????at?? d? te s?Áa p???s????Á??? ???????.

???a t?te ????? te d??????e? ?d’ ?p???????.

‘Before the city stands a lofty mound,

Each way encircled by the open plain;

Men call it Batiea; but the Gods

The tomb of swift Myrina; mustered there

The Trojans and Allies their troops arrayed.’

M.

Nikola´des gathers from this, that in front of Ilium there was a very

high hill, upon which the Trojan army of 50,000 men were marshalled in

battle-array. I, however, do not interpret the above lines by supposing

that the mound of Batiea was large and spacious, nor that 50,000 were

marshalled upon it in battle-array. On the contrary, when Homer uses

the word ‘a?p??’ for height, he always means ‘steep and lofty,’ and

upon a steep and lofty height 50,000 Trojans could not possibly have

been marshalled. Moreover, the poet expressly says that the steep hill

is called by the gods the tomb of the nimble-limbed Myrina,{180} while

‘Batiea,’ the name which men gave the hill, can signify only ‘the tomb

of Batiea.’ For, according to Apollodorus (iii. 12), Batiea was the

daughter of the Trojan King Teucer, and married Dardanus, who had

immigrated from Samothrace, and who eventually became the founder of

Troy.[180] Myrina was one of the Amazons who had undertaken the

campaign against Troy.[181] Homer can never have wished us to believe

that 50,000 warriors were marshalled upon a steep and lofty tumulus,

upon whose summit scarcely ten men could stand; he only wished to

indicate the locality where the Trojan army was assembled; they were

therefore marshalled round or beside the tumulus.

“M. Nikola´des

goes on to say, that such a hill still exists in front of Bunarbashi,

whereas there is no hill whatever, not even a mound, before Ilium

Novum. My answer to this is that in front of the heights of Bunarbashi

there are none of those conical tumuli called ‘s?Áata’ by Homer, that

however there must have been one in front of Hissarlik, where I am

digging, but it has disappeared, as do all earthen mounds when they are

brought under the plough.[182] Thus, for instance, M. Nikola´des,

during his one day’s residence in the Plain of Troy in the year 1867,

still found the tumulus of Antilochus near the Scamander, for he speaks

of it in his work published in the same year. I, too, saw the same

tumulus in August, 1868, but even then it had considerably decreased in

size, for it had just begun to be ploughed over, and now it has long

since disappeared.

“M. Nikola´des says that I am excavating in

New Ilium. My answer is that the city, whose depths I am investigating,

was throughout antiquity, nay from the time of its foundation to that

of its destruction, always simply called Ilium, and that no one ever

called it New Ilium, for everyone (p.181) believed that the city stood on

the site of the Homeric Ilium, and that it was identical with it. The

only person who ever doubted its identity with Ilium, the city of

Priam, was Demetrius of Scepsis, who maintained that the famous old

city had stood on the site of the village of the Ilians (?????? ??Á?),

which lies 30 stadia (3 geog. miles) to the south-east. This opinion

was afterwards shared by Strabo, who however, as he himself admits, had

never visited the Plain of Troy; hence he too calls the town ‘t?

s?Áe????? ?????,’ to distinguish it from the Homeric Ilium. My last

year’s excavations on the site of the ?????? ??Á? have, however, proved

that the continuous elevation on one side of it, which appeared to

contain the ruins of great town walls, contains in reality nothing but

mere earth. Wherever I investigated the site of the ancient village, I

always found the primary soil at a very inconsiderable depth, and

nowhere the slightest trace of a town ever having stood there. Hence

Demetrius of Scepsis and Strabo, who adopted his theory, were greatly

mistaken. The town of Ilium was only named Ilium Novum about 1000 years

after its complete destruction; in fact this name was only given to it

in the year 1788 by Lechevalier, the author of the theory that the

Homeric Ilium stood on the heights of Bunarbashi. Unfortunately,

however, as his work and map of the Plain of Troy prove, Lechevalier

only knew of the town from hearsay; he had never taken the trouble to

come here himself, and hence he has committed the exceedingly ludicrous

mistake, in his map, of placing his New Ilium 4╝ miles from Hissarlik,

on the other side of the Scamander, near Kum-kaleh.

“I wonder

where M. Nikola´des obtained the information that the city which he

calls Ilium Novum was founded by AstypalŠus in the sixth century B.C.

It seems that he simply read in Strabo (XIII. 602), that the

AstypalŠans, living in Rhœteum, built on the Simo´s the town of Polion

(which name passed over into Polisma), which, as (p.182) it had no natural

fortifications, was soon destroyed, and that he has changed this

statement of Strabo’s by making the AstypalŠans build Ilium Novum in

the sixth century B.C. In the following sentence Strabo says that the

town (Ilium) arose under the dominion of the Lydians, which began in

797 B.C. Whence can M. Nikola´des have obtained the information that

the foundation of the town was made in the sixth century?

“M.

Nikola´des further says that Homer certainly saw the successors of

Ăneas ruling in Troy, else he could not have put the prophecy of that

dynasty into the mouth of Poseidon.[183] I also entertained the same

opinion, until my excavations proved it to be erroneous, and showed

undoubtedly that Troy was completely destroyed, and rebuilt by another

people.

“As a further proof that the site of the Homeric Ilium

was on the heights of Bunarbashi, M. Nikola´des says that the Trojans

placed a scout on the tumulus of Ăsyetes, to watch when the AchŠans

would march forth from their ships, and he thinks that, on account of

the short distance from the Hellespont, this watching would have been

superfluous and unreasonable if, as I say, Troy had stood on the site

of Ilium, which M. Nikola´des calls Ilium Novum. I am astonished at

this remark of M. Nikola´des, for, as he can see from his own map of

the Plain of Troy, the distance from hence to the Hellespont is nearly

four miles, or 1Ż hour’s walk, whereas no human eye can recognise men

at a distance of 1 mile, much less at a distance of four. M.

Nikola´des, however, believes the tumulus of Ăsyetes to be the mound

called Udjek-TÚpÚ, which is 8 miles or 3Ż hours’ journey from the

Hellespont. But at such a distance the human eye could scarcely see the

largest ships, and could in no case recognise men. (p.183)

“In like

manner, the assertion of M. Nikola´des, that there is no spring

whatever near Hissarlik, is utterly wrong. It would be unfortunate for

me if this were true, for I have constantly to provide my 130 workmen

with fresh water to drink; but, thank God, close to my excavations,

immediately below the ruins of the town-wall, there are two beautiful

springs, one of which is even a double one. M. Nikola´des is also wrong

in his assertion that the Scamander does not flow, and never has

flowed, between Hissarlik and the Hellespont; for, as already stated,

the Scamander must at one time have occupied the large and splendid bed

of the Kalifatli-Asmak, which runs into the Hellespont near Cape

Rhœteum, and which is not given in the map of M. Nikola´des.

“Lastly,

he is completely wrong in his statement that the hill of Hissarlik,

where I am digging, lies at the extreme north-eastern end of the Plain

of Troy; for, as everyone may see by a glance at the map, the Plain

extends still further to the north-east an hour and a half in length

and half an hour in breadth, and only ends at the foot of the heights

of Renko´ and the ancient city of Ophrynium.

“It will be easily

understood that, being engaged with my superhuman works, I have not a

moment to spare, and therefore I cannot waste my precious time with

idle talk. I beg M. Nikola´des to come to Troy, and to convince himself

with his own eyes that, in refuting his erroneous statements, I have

described all I see here before me with the most perfect truth." (p.184)

Footnotes:

[174]

We do not feel it right to spoil the unity of the following

disquisition by striking out the few repetitions of arguments urged in

other parts of the work.—[Ed.]

[175] Strabo, XIII. i. p. 103; Lycophron, Cassandra, 1208. See further, on the Simo´s, Note A, p. 358.

[176] Odyssey, XXIV. 80-81:

Ἀμφ’ αὐτοῖσι δ’ ἔπειτα μέγαν καὶ ἀμύμονα τύμβον

Χεύαμεν Ἀργείων ἱερὸς στρατὸς αἰχμητάων,

Ἀκτῇ ἐπὶ προυχούσῃ, ἐπὶ πλατεῖ Ἑλλησπόντῳ,

Ὥς κεν τηλεφανὴς ἐκ ποντόφιν ἀνδράσιν εἴη

Τοῖς, οἳ νῦν γεγάασι, καὶ οἳ μετόπισθεν ἔσονται.

“We

the holy army of the spear-throwing Argives, then raised round these

(bones) a great and honourable tomb on the projecting shore of the

broad Hellespont, so that it might be seen from the sea by the men who

are now born and who shall be hereafter.”—Dr. Schliemann’s translation.

[177] Strabo, XIII. 1.

[178] Plutarch, ‘Life of Alexander the Great'; Cicero, pro Archia, 10; Ălian, V. H., 12, 7.

[179] Dio Cassius, LXXVII.

[180] Iliad, XX. 215-218.

[181] Herodotus, I. 27; Iliad, III. 189-190; Strabo, XIII. 3.

[182] But see further on this point, Chapter XI., pp. 197-8.—[Ed.]

[183] Iliad, XX. 307-308, quoted in the Introduction, p. 19.

[Continue to Chapter 11]

|

|