|

Chapter 11

On the Hill of Hissarlik, July 13th, 1872.

MyY last

report was dated the 18th of June. As the great extent of my

excavations renders it necessary for me to work with no less than 120

men, I have already been obliged, on account of the harvest season, to

increase the daily wages to 12 piasters since the 1st of June; but even

this would not have enabled me to collect the requisite number of men,

had not Mr. Max Müller, the German Consul in Gallipoli, had the

kindness to send me 40 workmen from that place. In consequence of this,

even during the busiest harvest season, I have always had from 120 to

130 workmen, and now that the harvest is over, I have constantly 150.

To facilitate the works, I have procured, through the kindness of the

English Consul in Constantinople, Mr. Charles Cookson, 10 “man-carts,”

which (p.185) are drawn by two men and pushed by a third. The same

gentleman also sent me 20 wheel-barrows, so that I now work with 10

man-carts and 88 wheel-barrows. In addition to these I keep six more

carts with horses, each of which costs 5 francs a day, so that the

total cost of my excavations amounts to more than 400 francs (16l.) a

day. Besides battering-rams, chains, and windlasses, my implements

consist of 24 large iron levers, 108 spades, and 103 pickaxes, all of

the best English manufacture. From sunrise to sunset all are busily at

work, for I have three capital foremen, and my wife and I are always

present at the works. But for all this I do not think that I now remove

more than 400 cubic yards of débris in a day, for the distance is

always increasing, and in several places it is already more than 262

feet. Besides this, the continual hurricane from the north, which

drives the dust into our eyes and blinds us, is exceedingly disturbing.

This perpetual high wind is perhaps explained by the fact that the Sea

of Marmora, with the Black Sea behind it, is connected with the Ægean

Sea by a strait comparatively so narrow. Now, as such perpetual high

winds are unknown in any other part of the world, Homer must have lived

in the Plain of Troy, otherwise he would not have so often given to his

????? the appropriate epithet of “??eµ?essa” (the “windy” or “stormy”),

which he gives to no other place.

As I have already said, at a

perpendicular depth of 12 meters (39½ feet) below the summit of the

hill (on the site of what is probably the temple built by Lysimachus) I

have dug a platform, 102 feet broad below and 112 feet wide at the top:

it already extends to a length of 82 feet. But to my great alarm I find

that I have made it at least 5 meters (16½ feet) too high; for, in

spite of the great depth and the great distance from the declivity of

the hill, I am here still in the débris of the Greek colony, whereas on

the northern declivity of the hill I generally reached the (p.186) ruins

of the preceding people at a depth of less than 6½ feet. To make the

whole platform 16½ feet lower would be a gigantic piece of work, for

which I have no patience at present, on account of the advanced season

of the year. But in order as soon as possible to find out what lies

hidden in the depths of this temple, I have contented myself with

making a cutting 26 feet broad above and 13 feet wide below, exactly

16¼ feet below the platform and in the centre of it. This cutting I am

having dug out at the same time from below and on two terraces, so it

advances rapidly.

Since the discovery of the Sun-god with the

four horses, many blocks of marble with representations of suns and

flowers have been found, but no sculptures of any importance. As yet

very few other objects have been brought to light from the excavation

of the temple; only a few round terra-cottas with the usual decoration

of the central sun surrounded by three, four, or five triple or

quadruple rising suns; knives of silex in the form of saws, a few

pretty figures in terra-cotta, among which is a priestess with very

expressive Assyrian features, with a dress of a brilliant red and green

colour, and a red cloth round her head; also a small bowl, the lower

end of which represents the head of a mouse. The mouse, it is well

known, is a creature inspired by the vapours of the earth, and, as the

symbol of wisdom, was sacred to Apollo. According to Strabo (XIII. p.

613) Apollo is said to have caused mice to show the Teucrians, who

migrated from Crete, the place where they were to settle. However, the

bowl with the head of a mouse is no more a proof that the temple built

here by Lysimachus was dedicated to Apollo than is the metopé

representing the Sun-god with four horses.

In the other parts of

my excavations, since my last report, we have again brought to light an

immense number of round terra-cottas, and among them, from a depth of

from 4 to 10 meters (13 to 33 feet), a remarkable number (p.187) with

three, four, or five ? round the central sun.[184] One, from a depth of

23 feet,[185] shows the central sun surrounded by six suns, through

each of which a ? passes; upon another, found at a depth of 33 feet,

the central sun has 12 trees instead of rays;[186] upon a third,

brought from a depth of 16½ feet, the sun has seven rays in the form of

fishing-hooks, one in the form of the figure three and two in the shape

of the Phœnician letter Nun, then follow 12 sheaves of rays, in each of

which are four little stars; upon a fourth terra-cotta, which I found

at a depth of 16½ feet, there are four rising suns and a tree in the

circle round the sun.[187] I very frequently find between the rising

suns three or four rows of three dots running towards the central

sun,[188] which, as already said, according to É. Burnouf, denote

“royal majesty” in the Persian cuneiform inscriptions. It is certain

that this symbol is here also intended to glorify the Sun-god. At a

depth of from 7 to 10 meters (23 to 33 feet) we also find round

terra-cottas, upon which the entire surface round the sun is filled

with little stars, and in addition only one ?.

During the last

few days we have also found, in the strata next above the primary soil,

at a depth of from 46 to 36 feet, a number of round brilliant black

terra-cottas of exquisite workmanship; most of them much flatter than

those occurring in the higher strata, and resembling a wheel; many are

in the shape of large flat buttons.[189] But we also meet with some in

the form of tops and volcanoes, which differ from those found in the

higher strata only by the fineness of the terra-cotta and by their

better workmanship. The decorations on these very ancient articles are,

however, generally much simpler than (p.188) those met with above a depth

of 10 meters (33 feet), and are mostly confined to the representation

of the sun with its rays, or with stars between the latter, or of the

sun in the centre of a simple cross, or in the middle of four or five

double or treble rising suns. At a depth of 6 meters (20 feet) we again

found a round terra-cotta in the form of a volcano, upon which are

engraved three antelopes in the circle round the sun.

At a depth

of from 5 to 8 meters (16½ to 26 feet) a number of terra-cotta balls

were found, the surface of each being divided into eight fields; these

contain a great many small suns and stars, either enclosed by circles

or standing alone. Most of the balls, however, are without divisions

and covered with stars; upon some I find the ? and the tree of life,

which, as already said, upon a terra-cotta ball found at a depth of 26

feet, had stars between its branches.

Fig.143: Terra-cotta Ball, representing apparently the climates of the globe (8m depth).[190]

Among

the thousands and thousands of round terra-cottas in the form of the

volcano, the top, or the wheel, (p.189) which are found here from the

surface down to a depth of from 14 and 16 meters (46 to 53 feet)—that

is, from the end of the Greek colony down to the ruined strata of the

first inhabitants, I have not yet found a single one with symbolical

signs, upon which I could discover the slightest trace that it had been

used for any domestic purpose.[191] On the other hand, among those

which have no decorations I find a few, perhaps two in a hundred, of

those in the form of volcanoes, the upper surfaces of which show

distinct traces of rubbing, as if from having been used on the

spinning-wheel or loom. That these articles, which are frequently

covered with the finest and most artistic engravings, should have

served as weights for fishing-nets, is utterly inconceivable, for,

apart from all other reasons opposed to such a supposition, pieces of

terra-cotta have not the requisite weight, and of course are directly

spoilt by being used in water.

M. É. Burnouf writes to me, that

these exceedingly remarkable objects were either worn by the Trojans

and their successors as amulets, or must have been used as coins. Both

of these suppositions, however, seem to me to be impossible. For

amulets they are much too large and heavy, for they are from above 1

inch to nearly 2 inches, and some even 2-1/3 inches, in diameter, and

from 3/5 of an inch to nearly 2 inches high; moreover, it would be most

uncomfortable to wear even a single one of these heavy pieces on the

neck or breast. That they were used as coins appears to me

inconceivable, on account of the religious symbols; moreover, if they

had been so used, they would show traces of wear from their continual

transfer. The white substance with which the engravings are filled

seems also to contradict their having been used as coins; for in their

constant passage from hand to hand it would have soon disappeared.

Lastly, (p.190) such an use is inconsistent with the fact that they also

occur in the strata of the Greek colony, in which I find a number of

copper and some silver coins of Ilium. However, the latter belong for

the most part to the time of the Roman emperors, and I cannot say with

certainty that they reach back beyond our Christian era. There are,

however, coins of Sigeum, which probably belong to the second century

before Christ, for in Strabo’s time this town was already destroyed.

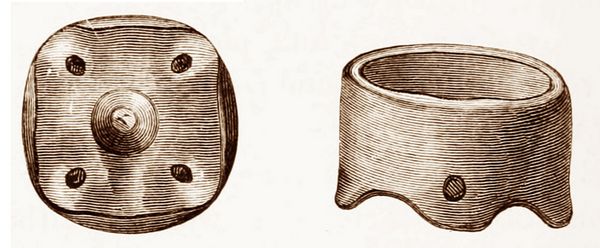

Fig.144: Small Terra-cotta Vessel from the lowest Stratum, with four

perforated feet, and one foot in the middle (14m depth.).[192]

At

a depth of 14 meters (46 feet) I find, among other curious objects,

small round bowls only 1¾ inch in diameter; some of them have, on the

edge of the bottom, four little feet with a perforated hole, and in the

centre a fifth little foot without a hole. Other bowls of the same size

have four little feet, only two of which have a perforated hole. My

conjecture is that all of these small bowls, which could both stand and

be hung up, were used by the ancient Trojans as lamps. Among the ruins

of the three succeeding nations I find no trace of lamps, and only at a

depth of less than a meter (3¼ feet) do I find Greek ??????.

At

the depth of 2 meters (6½ feet) I found, among the ruins of a house, a

great quantity of very small bowls, only 3-4ths of an inch high and

2-5ths of an (p.191) inch broad, together with their small lids; their use

is unknown to me. At all depths below 4 meters (13 feet) I find the

small flat saucers of from nearly 2 inches to above 3 inches in

diameter, with two holes opposite each other; from 4 to 7 meters (13 to

23 feet) they are coarse, but from 7 to 10 meters (23 to 33 feet) they

are finer, and from 13 to 14 meters (42½ to 46 feet) they are very

fine. I am completely ignorant as to what they can

have been used for.

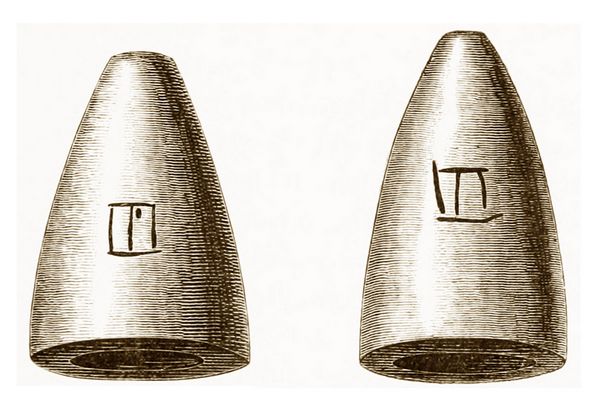

At all these depths I also find funnels from 2¾ to above 3 inches long,

the broad end of which is only a little above an inch in diameter. In

the upper strata they are made of very coarse clay, but at an

increasing depth they gradually become better, and at a depth of 46

feet they are made of very good terra-cotta.

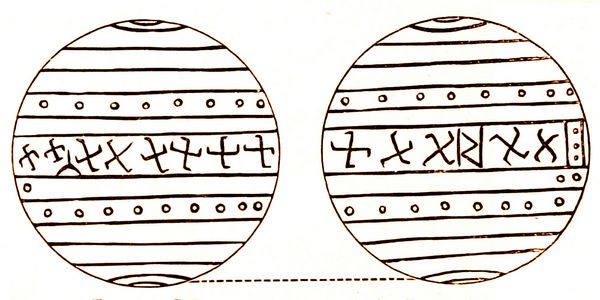

Figs.145,146: Two little Funnels of Terra-cotta, inscribed with Cyprian Letters (3m depth.).

It is extremely

remarkable, however, that these curious and very “unpractical” funnels

were kept in use in an entirely unchanged pattern by all the tribes

which inhabited Ilium from the foundation of the city to before the

Greek colony. I also find, in the second and third strata, terra-cottas

in the form of the primitive canoes which were made of the hollowed

trunk of a tree. From 4 to 7 meters (13 to 23 feet) they are coarse,

and about 4 inches long; at a depth of from 7 to 10 meters (23 to 33

feet) they are finer, and from 1½ to 2¾ inches long. They may have been

used as salt-cellars or pepper-boxes; I found several with flat

lids. (p.192) These vessels cease to be found in the lowest stratum.

Miniature vases and pots, between 1 and 2 inches high, are frequently

found in all the strata from a depth of from 10 to 33 feet; at a depth

of from 46 to 52½ feet only three miniature pots were discovered; one

is not quite an inch high. At a depth of 5 meters (16½ feet) we found a

perfectly closed earthen vessel with a handle, which seems to have been

used as a bell, for there are pieces of metal inside of it which ring

when it is shaken.

Of

cups (vase-covers) with owls’ heads and helmets, since my last report

two have been brought out from a depth of 10 and 11 feet, two from 16

feet and one from 26 feet. The first are made of bad terra-cotta and

are inartistic; those from a depth of 16 feet are much better finished

and of a better clay; while that from 26 feet (8 meters) is so

beautiful, that one is inclined to say that it represents the actual

portrait of the goddess with the owl’s face.[193] During these last few

days we have found a number of those splendid red cups in the form of

large champagne glasses, without a foot, but with two enormous handles,

one of which was 10½ inches high; but I have already found one 12½

inches in height.

From a depth of from 26 to 33 feet we have also

brought out many small pots with three little feet, with rings at the

sides and holes in the mouth for hanging up, and with pretty engraved

decorations. Upon the whole, we have (p.193) met with many beautiful

terra-cottas from all the strata during the last few days.

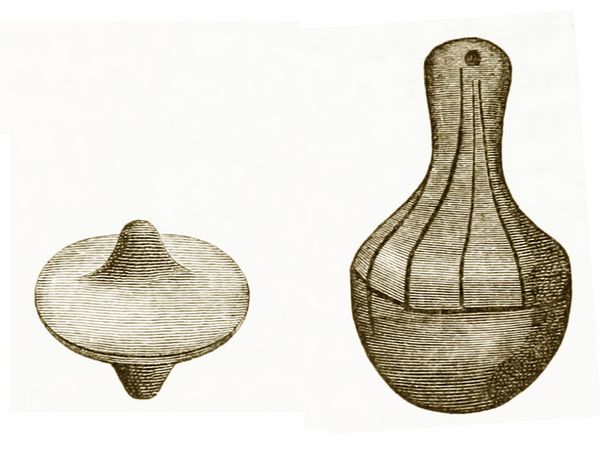

Fig.147 (left): A Trojan Humming-top (7m depth.).

Fig.148 (right): Terra-cotta Bell, or Clapper, or Rattle (5m depth)

I

have still to describe one of those very pretty vases which occur

abundantly at the depth of from 7 to 10 meters (23 to 33 feet), and

have either two closed handles, or, in place of them, two handles with

perforated holes, and also two holes in the mouth in the same

direction; thus they could stand or be hung up by means of strings

drawn through the four holes. They have in most cases decorations all

round them, which generally consist, above and below, of three parallel

lines drawn round them horizontally; between these there are 24

perpendicular lines, which likewise run parallel; the spaces formed by

the latter are filled alternately with three or six little stars.[194]

At a depth of from 7 to 10 meters (23 to 33 feet) we also meet,

although seldom, with vases having cuneiform decorations. I must,

however, remind the reader that all the decorations met with here, at a

depth of from 33 feet up to 6½ feet, have always been more or less

artistically engraved upon the terra-cottas when they were still soft

and unburnt, that all of the vases have a uniform colour (though the

ordinary pots are in most cases uncoloured), and that we have never

found a trace of painting in these depths, with the exception of a

curious box in the form of a band-box, found at a depth of 8 meters (26

feet), which has three feet as well as holes for hanging it up. It is

adorned on all sides with red decorations on a yellow ground, and on

its lid there is a large ? or a very similar symbol of the Maya, the

fire-machine of our Aryan forefathers.

In the lowest stratum

also, at the depth of 52½ feet, I found only the one fragment, already

described, of a vase with an actual painting.[195] All of the other

vessels found in these strata, even the round terra-cottas in the form

of wheels, volcanoes, or tops, are of a brilliant{194} black, red or

brown colour, and the decorations are artistically engraved and filled

with a white substance, so as to be more striking to the eye.

As

every object belonging to the dark night of the pre-Hellenic times, and

bearing traces of human skill in art, is to me a page of history, I am,

above all things, obliged to take care that nothing escapes me. I

therefore pay my workmen a reward of 10 paras (5 centimes, or a

half-penny) for every object that is of the slightest value to me; for

instance, for every round terra-cotta with religious symbols. And,

incredible as it may seem, in spite of the enormous quantities of these

articles that are discovered, my workmen have occasionally attempted to

make decorations on the unornamented articles, in order to obtain the

reward; the sun with its rays is the special object of their industry.

I, of course, detect the forged symbols at once, and always punish the

forger by deducting 2 piasters from his day’s wages; but, owing to the

constant change of workmen, forgery is still attempted from time to

time.

As I cannot remember the names of the men engaged in my

numerous works, I give each a name of my own invention according to

their more or less pious, military or learned appearance: dervish,

monk, pilgrim, corporal, doctor, schoolmaster, and so forth. As soon as

I have given a man such a name, the good fellow is called so by all as

long as he is with me. I have accordingly a number of Doctors, not one

of whom can either read or write.

Yesterday, at a depth of 13

meters (43½ feet), between the stones of the oldest city, I again came

upon two toads, which hopped off as soon as they found themselves free.

In

my last report I did not state the exact number of springs in front of

Ilium. I have now visited all the springs myself, and measured their

distance from my excavations, and I can give the following account of

them. The first spring, which is situated directly below the ruins of

the ancient town-wall, is exactly 365 meters (399 yards) (p.195) from my

excavations; its water has a temperature of 16° Celsius (60.8°

Fahrenheit). It is enclosed to a height of 6½ feet by a wall of large

stones joined with cement, 9¼ feet in breadth, and in front of it there

are two stone troughs for watering cattle. The second spring, which is

likewise still below the ruins of the ancient town-wall, is exactly 725

meters (793 yards) distant from my excavations. It has a similar

enclosure of large stones, 7 feet high and 5 feet broad, and has the

same temperature. But it is out of repair, and the water no longer runs

through the stone pipe in the enclosure, but along the ground before it

reaches the pipe. The double spring spoken of in my last report is

exactly 945 meters (1033 yards) from my excavations. It consists of two

distinct springs, which run out through two stone pipes lying beside

each other in the enclosure composed of large stones joined with earth,

which rises to a height of 7 feet and is 23 feet broad; its temperature

is 17° Celsius (62.6° Fahrenheit). In front of these two springs there

are six stone troughs, which are placed in such a manner that the

superfluous water always runs from the first trough through all the

others. It is extremely probable that these are the two springs

mentioned by Homer, beside which Hector was killed.[196] When the

poet (p.196) describes the one as boiling hot, the other as cold as ice,

this is probably to be understood in a metaphorical sense; for the

water of both these springs runs into the neighbouring Simoïs, and

thence into the Kalifatli-Asmak, whose enormous bed was at one time

occupied by the Scamander; the latter, however, as is well known, comes

from Mount Ida from a hot and a cold spring.

I remarked in my

last memoir that the Doumbrek-Su (Simoïs) still flows past the north of

Ilium into the former channel of the Scamander, and I afterwards said

that one of its arms flowed into the sea near Cape Rhœteum. This remark

requires some explanation. The sources of the Simoïs lie at a distance

of eight hours from Hissarlik; and, as far down as the neighbouring

village of Chalil-Koï, though its water is drawn off into four

different channels for turning mills, its great bed has always an

abundance of water even during the hottest summer weather. At

Chalil-Koï, however, it divides itself into two arms; one of which,

after it has turned a mill, flows into the Plain in a north-westerly

direction, forms an immense marsh, and parts into two branches, one of

which again falls into the other arm, which flows in a westerly

direction from Chalil-Koï, and then empties itself directly into the

Kalifatli-Asmak, the ancient bed of the Scamander. The other arm of the

Simoïs, which flowed in a north-westerly direction from Chalil-Koï,

after it has received a tributary from the Kalifatli-Asmak by means of

an artificial canal, turns direct{197} north, and, under the name of

In-tépé-Asmak, falls into the Hellespont through an enormously broad

bed, which certainly was at one time occupied by the Kalifatli-Asmak,

and in remote antiquity by the Scamander, and is close to the

sepulchral mound of Ajax, which is called In-tépé. I must draw

attention to the fact that the name of Ajax (??a?, gen. ??a?t??) can

even be recognised in the Turkish name (In-tépé: Tépé signifies “hill.”)

In

returning to the article by M. Nikolaïdes, I can now also refute his

assertion that near Ilium, where I am digging, there is no hill which

can be regarded as the one described by Homer as the tomb of Batiea or

the Amazon Myrina.[197]

Strabo (XIII. i. p. 109) quotes the

lines already cited from the Iliad [198] (II. 790-794) as an argument

against the identity of Ilium with the Ilium of Priam, and adds: “If

Troy had stood on the site of the Ilium of that day, Polites would have

been better able to watch the movements of the Greeks in the ships from

the summit of the Pergamus than from the tumulus of Æsyetes, which lies

on the road to Alexandria Troas, 5 stadia (half a geographical mile)

from Ilium.”

Strabo is perfectly right in saying that the Greek

camp must have been more readily seen from the summit of the Pergamus

than from a sepulchral mound on the road to Alexandria Troas, 5 stadia

from Ilium; for Alexandria Troas lies to the south-west of Ilium, and

the road to it, which is distinctly marked by the ford of the Scamander

at its entrance into the valley, goes direct south as far as

Bunarbashi, whereas the Hellespont and the Greek camp were north of

Ilium. But to the south of Ilium, exactly in the direction where the

road to Alexandria Troas must have been, I see before me a tumulus 33

feet high and 131 yards in circumference, and, according to an exact

measurement (p.198) which I have made, 1017 yards from the southern city

wall. This, therefore, must necessarily be the sepulchral mound of

which Strabo writes; but he has evidently been deceived in regard to

its identity with the tumulus of Æsyetes by Demetrius of Scepsis, who

wished to prove the situation of this mound to be in a straight line

between the Greek camp and the village of the Ilians (?????? ??µ?), and

the latter to be the site of Troy. The tumulus of Æsyetes was probably

situated in the present village of Kum-Koï, not far from the confluence

of the Scamander and the Simoïs, for the remains of an heroic tumulus

several feet in height are still to be seen there.

The mound now

before me is in front of Troy, but somewhat to the side of the Plain,

and this position corresponds perfectly with the statements which Homer

gives us of the position of the monument of Batiea or the Amazon

Myrina: “p??p?????e p?????” and “?? ped?? ?p??e??e.” This tumulus is

now called Pacha-Tépé.

We may form an idea of what a large

population Ilium possessed at the time of Lysimachus, among other

signs, from the enormous dimensions of the theatre which he built; it

is beside the Pergamus where I am digging, and its stage is 197 feet in

breadth.

The heat during the day, which is 32° Celsius (89.6°

Fahrenheit), is not felt at all, owing to the constant wind, and the

nights are cool and refreshing.

Our greatest plague here, after

the incessant and intolerable hurricane, is from the immense numbers of

insects and vermin of all kinds; we especially dread the scorpions and

the so-called Sa?a?t?p?d?a (literally “with forty feet”—a kind of

centipede), which frequently fall down from the ceiling of the rooms

upon or beside us, and whose bite is said to be fatal.

I cannot

conclude without mentioning an exceedingly remarkable person,

Konstantinos Kolobos, the owner of a shop in the village of Neo-Chorion

in the Plain of Troy, (p.199) who, although born without feet, has

nevertheless made a considerable fortune in a retail business. But his

talents are not confined to business; they include a knowledge of

languages; and although Kolobos has grown up among the rough and

ignorant village lads and has never had a master, yet by self-tuition

he has succeeded in acquiring the Italian and French languages, and

writes

Fig.149: A Trojan decorated Vase of Terra-cotta (7m depth).

and speaks both of them perfectly. He is also wonderfully expert

in ancient Greek, from having several times copied and learnt by heart

a large etymological dictionary, as well as from having read all the

classic authors, and he can repeat whole rhapsodies from the Iliad by

heart. What a pity it is that such a genius has to spend his days in a

wretched village in the Troad, useless to the world, and in the

constant company of the most uneducated and ignorant people, all of

whom gaze at him in admiration, but none of whom understand him!

Footnotes:

[184] See the Plates of Whorls, Nos. 350, 351, 352, 356, 357, 359, &c.

[185] Plate XXVI., No. 362. M. Burnouf calls these “the 6 bi-monthly sacrifices.”

[186] Plate XXXIII., No. 402.

[187] Plate XXXIV., No. 403.

[188] Plate XXII., No. 320.

[189] See the Sections on Plate XXI.

[190]

In the ball here depicted there is no mistaking the significance of the

line of ?, the symbols of fire, as denoting the torrid zone. The three

dots are, according to M. Burnouf, the symbol of royal majesty therein

residing. The two rows of dots parallel to the torrid zone may possibly

represent the inhabited regions of the temperate zones, according to

the oriental theory followed by Plato.—[Ed.]

[191] See the qualification of this statement on p. 40.

[192] In the Atlas, Dr. Schliemann describes this and another such as Trojan lamps, but adds that they may be only vase covers.

[193] The one meant seems to be that engraved on p. 115 (No. 74).

[194] See Cut, No. 149, p. 199.

[195] See Cut, No. 1, p. 15.

[196] Iliad, XXII. 145-156:—

?? d? pa?? s??p??? ?a? ????e?? ??eµ?e?ta

?e??e?? a??? ?p?? ?at’ ?µa??t?? ?sse???t?,

?????? d’ ??a??? ?a???????, ???a te p??a?

???a? ??a?ss??s? S?aµ??d??? d???e?t??.

? µ?? ??? ?’ ?dat? ??a?? ??e?, ?µf? d? ?ap???

G???eta? ?? a?t?? ?? e? p???? a???µ??????

? d’ ?t??? ???e? p????e? ?????a ?a????

? ????? ????? ? ?? ?dat?? ???st????.

???a d’ ?p’ a?t??? p????? e???e? ????? ?as??

?a??? ?a??e??, ??? e?µata s??a??e?ta

????es??? ????? ?????? ?a?a? te ???at?e?

?? p??? ?p’ e??????, p??? ???e?? ??a? ??a???.

“They” (Hector and Achilles, in flight and pursuit)

“They by the watch-tower, and beneath the wall

Where stood the wind-beat fig-tree, raced amain

Along the public road, until they reached

The fairly-flowing founts, whence issued forth,

From double source, Scamander’s eddying streams.

One with hot current flows, and from beneath,

As from a furnace, clouds of steam arise;

‘Mid Summer’s heat the other rises cold

As hail, or snow, or water crystallized;

Beside the fountains stood the washing-troughs

Of well-wrought stone, where erst the wives of Troy

And daughters fair their choicest garments washed,

In peaceful times, ere came the sons of Greece.”

[197] See Iliad, II. 811-815, quoted above, p. 179.

[198] Chapter II., p. 69.

[Continue to Chapter 12]

|

|