|

Chapter 6:

Work at Hissarlik in 1872.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, April 5th, 1872.

MY

last report was dated November 24th, 1871. On the first of this month,

at 6 o’clock on the morning of a glorious day, accompanied by my wife,

I resumed the excavations with 100 Greek workmen from the neighbouring

villages of Renkoï, Kalifatli, and Yenishehr. Mr. John Latham, of

Folkestone, the director of the railway from the Piræus to Athens, who

by his excellent management brings the shareholders an annual dividend

of 30 per cent., had the kindness to give me two of his best workmen,

Theodorus Makrys of Mitylene, and Spiridion Demetrios of Athens, as

foremen.

To each of them I pay 150 fr. (6l.) per month, while the daily

wages of the other men are but 1 fr. 80 cent. Nikolaos Zaphyros, of

Renkoï, gets 6 fr., as formerly; he is of great use to me on account of

his local knowledge, and serves me at once as cashier, attendant, and

cook. Mr. Piat, who has undertaken the construction of the railroad

from the Piræus to Lanira, has also had the kindness to let me have his

engineer, Adolphe Laurent, for a month, whom I shall have to pay 500

fr. (20l.), and his travelling expenses. But in addition{99} there are

other considerable expenses to be defrayed, so that the total cost of

my excavations amounts to no less than 300 fr. (12l.) daily.

Now

in order to be sure, in every case, of thoroughly solving the Trojan

question this year, I am having an immense horizontal platform made on

the steep northern slope, which rises at an angle of 40 degrees, a

height of 105 feet perpendicular, and 131 feet above the level of the

sea. The platform extends through the entire hill, at an exact

perpendicular depth of 14 meters or 46½ English feet, it has a breadth

of 79 meters or 233 English feet, and embraces my last year’s

cutting.[102] M. Laurent calculates the mass of matter to be removed at

78,545 cubic meters (above 100,000 cubic yards): it will be less if I

should find the native soil at less than 46 feet, and greater if I

should have to make the platform still lower. It is above all things

necessary for me to reach the primary soil, in order to make accurate

investigations.

To make the work easier, after having had the

earth on the northern declivity picked down in such a manner that it

rises perpendicularly to the height of about 8½ feet from the bottom,

and after that at an angle of 50 degrees, I continue to have the débris

of the mighty earth wall loosened in such a manner that this angle

always remains exactly the same. In this way I certainly work three

times more rapidly than before, when, on account of the small breadth

of the channel, I was forced to open it on the summit of the hill in a

direct horizontal direction along its entire length. In spite of every

precaution, however, I am unable to guard my men or myself against the

stones which continually come rolling down, when the steep wall is

being picked away. Not one of us is without several wounds in his feet.

During

the first three days of the excavations, in{100} digging down the slope

of the hill, we came upon an immense number of poisonous snakes, and

among them a remarkable quantity of the small brown vipers called

antelion (??t?????), which are scarcely thicker than rain worms, and

which have their name from the circumstance that the person bitten by

them only survives till sunset. It seems to me that, were it not for

the many thousands of storks which destroy the snakes in spring and

summer, the Plain of Troy would be uninhabitable, owing to the

excessive numbers of these vermin.

Through the kindness of my

friends, Messrs. J. Henry Schröder and Co., in London, I have obtained

the best English pickaxes and spades for loosening and pulling down the

rubbish, also 60 excellent wheel-barrows with iron wheels for carrying

it away.

For the purpose of consolidating the buildings on the

top of the hill, the whole of the steep northern slope has evidently

been supported by a buttress, for I find the remains of one in several

places. This buttress is however not very ancient, for it is composed

of large blocks of shelly limestone, mostly hewn, and joined with lime

or cement. The remains of this wall have only a slight covering of

earth; but on all other places there is more or less soil, which, at

the eastern end of the platform, extends to a depth of between 6½ and

10 feet.

Behind the platform, as well as behind the remains of

the buttress, the débris is as hard as stone, and consists of the ruins

of houses, among which I find axes of diorite, sling-bullets of

loadstone, a number of flint knives, innumerable handmills of lava, a

great number of small idols of very fine marble, with or without the

owl’s-head and woman’s girdle, weights of clay in the form of pyramids

and with a hole at the point, or made of stone and in the form of

balls; lastly, a great many of those small terra-cotta whorls, which

have already been so frequently spoken of in my previous reports.

Two

pieces of this kind, with{101} crosses on the under side, were found in

the terramares of Castione and Campeggine,[103] and are now in the

Museum of Parma. Many of these Trojan articles, and especially those in

the form of volcanoes, have crosses of the most various descriptions,

as may be seen in the lithographed drawings.[104] The form block-style

cross occurs especially often; upon a great many we find the sign ?, of

which there are often whole rows in a circle round the central point.

In my earlier reports I never spoke of these crosses, because their

meaning was utterly unknown to me.

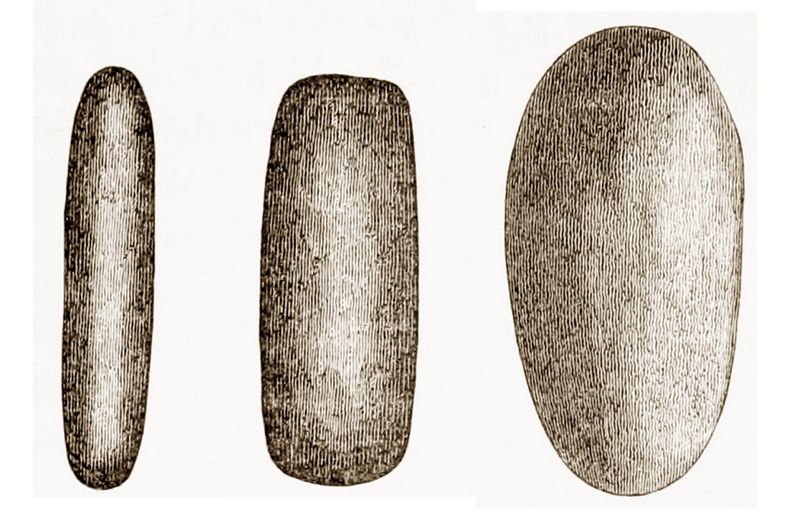

Figs.66, 67, 68: Trojan Sling-bullets of Loadstone (9 and 10m depth).

This

winter, I have read in Athens many excellent works of celebrated

scholars on Indian antiquities, especially Adalbert Kuhn, Die

Herabkunft des Feuers; Max Müller’s Essays; Émile Burnouf, La Science

des Religions and Essai sur le Vêda, as well as several works by Eugène

Burnouf; and I now perceive that these crosses upon the Trojan

terra-cottas are of the highest importance to archæology.

I

therefore consider it necessary to enter more fully into the subject,

all the more so as I am now able to prove that both the block-style

cross and the ?, which I find in Émile Burnouf’s Sanscrit lexicon,

under the name of “suastika,” and with the meaning e? ?st?, or as the

sign of good wishes, were already regarded, thousands of years

before{102} Christ, as religious symbols of the very greatest

importance among the early progenitors of the Aryan races in Bactria

and in the villages of the Oxus, at a time when Germans, Indians,

Pelasgians, Celts, Persians, Slavonians and Iranians still formed one

nation and spoke one language.

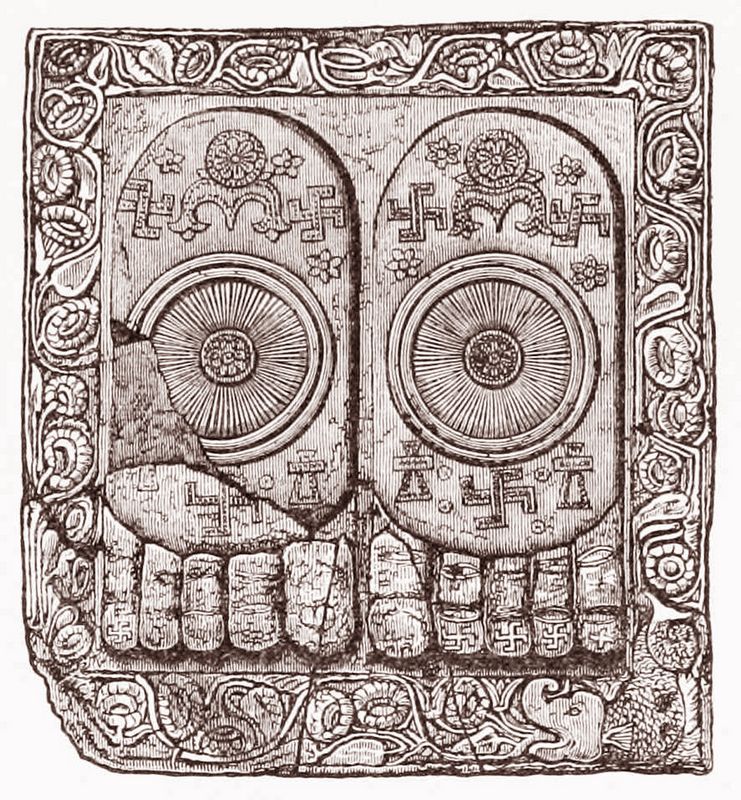

For I recognise at the first

glance the “suastika” upon one of those three pot bottoms,[105] which

were discovered on Bishop’s Island near Königswalde on the right bank

of the Oder, and have given rise to very many learned discussions,

while no one recognised the mark as that exceedingly significant

religious symbol of our remote ancestors. I find a whole row of these

“suastikas” all round the famous pulpit of Saint Ambrose in Milan; I

find it occurring a thousand times in the catacombs of Rome.[106] I

find it in three rows, and thus repeated sixty times, upon an ancient

Celtic funereal urn discovered in Shropham in the county of Norfolk,

and now in the British Museum.[107] I find it also upon several

Corinthian vases in my own collection, as well as upon two very ancient

Attic vases in the possession of Professor Kusopulos at Athens, which

are assigned to a date as early, at least, as 1000 years before Christ.

I likewise find it upon several ancient coins of Leucas, and in the

large mosaic in the royal palace garden in Athens.

An English

clergyman, the Rev. W. Brown Keer, who visited me here, assures me that

he has seen the ? innumerable times in the most ancient Hindu temples,

and especially in those of Gaïna.[108] I find in the Ramayana that the

ships of king{103} Rama—in which he carried his troops across the

Ganges on his expedition of conquest to India and Ceylon—bore the ? on

their prows. Sanscrit scholars believe that this heroic epic (the

Ramayana) was composed at the latest 800 years before Christ, and they

assign the campaign of Rama at the latest to the thirteenth or

fourteenth century B.C., for, as Kiepert points out in his very

interesting article in the National-Zeitung, the names of the products

mentioned in the 2nd Book of Kings, in the reign of King Solomon, as

brought by Phœnician ships from Ophir, as for example, ivory, peacocks,

apes and spices, are Sanscrit words with scarcely any alteration.

Fig.69: The Foot-print of Buddha (carved on the Amraverti Tope, near the river Kistna; cf. footnote 8).

Émile

Burnouf, in his excellent work La Science des Religions, just

published, says, “The ? represents the two pieces of wood which were

laid cross-wise upon one{104} another before the sacrificial altars in

order to produce the holy fire (Agni), and whose ends were bent round

at right angles and fastened by means of four nails, suastika with

dots, so that this wooden scaffolding might not be moved. At the point

where the two pieces of wood were joined, there was a small hole, in

which a third piece of wood, in the form of a lance (called Pramantha)

was rotated by means of a cord made of cow’s hair and hemp, till the

fire was generated by friction.

The father of the holy fire

(Agni) is Twastri, i.e. the divine carpenter, who made the ? and the

Pramantha, by the friction of which the divine child was produced. The

Pramantha was afterwards transformed by the Greeks into Prometheus,

who, they imagined, stole fire from heaven, so as to instil into

earth-born man the bright spark of the soul. The mother of the holy

fire is the divine Mâjâ, who represents the productive force in the

form of a woman; every divine being has his Mâjâ. Scarcely has the weak

spark escaped from its mother’s lap, that is from the ?, which is

likewise called mother, and is the place where the divine Mâjâ

principally dwells—when it (Agni) receives the name of child.

In

the Rigvêda we find hymns of heavenly beauty in praise of this new-born

weak divine creature. The little child is laid upon straw; beside it is

the mystic cow, that is, the milk and butter destined as the offering;

before it is the holy priest of the divine Vâju, who waves the small

oriental fan in the form of a flag, so as to kindle life in the little

child, which is close upon expiring. Then the little child is placed

upon the altar, where, through the holy “sôma” (the juice of the tree

of life) poured over it, and through the purified butter, it receives a

mysterious power, surpassing all comprehension of the worshippers. The

child’s glory shines upon all around it; angels (dêvâs) and men shout

for joy, sing hymns in its praise, and throw themselves on their faces

before it. On its left is the rising sun, on its right the full moon on

the horizon, and both appear to grow{105} pale in the glory of the

new-born god (Agni) and to worship him.

But how did this

transfiguration of Agni take place? At the moment when one priest laid

the young god upon the altar, another poured the holy draught, the

spiritual “sôma” upon its head, and then immediately anointed it by

spreading over it the butter of the holy sacrifice. By being thus

anointed Agni receives the name of the Anointed (akta); he has,

however, grown enormously through the combustible substances; rich in

glory he sends forth his blazing flames; he shines in a cloud of smoke

which rises to heaven like a pillar, and his light unites with the

light of the heavenly orbs. The god Agni, in his splendour and glory,

reveals to man the secret things; he teaches the Doctors; he is the

Master of the masters, and receives the name of Jâtavêdas, that is, he

in whom wisdom is in-born.

Upon my writing to M. É. Burnouf to

enquire about the other symbol, the cross in the form block-style

cross, which occurs hundreds of times upon the Trojan terra-cottas, he

replied, that he knows with certainty from the ancient scholiasts on

the Rigvêda, from comparative philology, and from the Monuments

figurés, that Suastikas, in this form also, were employed in the very

remotest times for producing the holy fire. He adds that the Greeks for

a long time generated fire by friction, and that the two lower pieces

of wood that lay at right angles across one another were called

“sta????,” which word is either derived from the root “stri,” which

signifies lying upon the earth, and is then identical with the Latin

“sternere,” or it is derived from the Sanscrit word “stâvara,” which

means firm, solid, immovable. Since the Greeks had other means of

producing fire, the word sta???? passed into simply in the sense of

“cross.”

Other passages might be quoted from Indian scholars to

prove that from the very remotest times the ? and the block-style cross

were the most sacred symbols of our Aryan forefathers.{106}

In my present excavations I shall probably find a

definite explanation as to the purpose for which the articles

ornamented with such significant symbols were used; till then I shall

maintain my former opinion, that they either served as Ex votos or as

actual idols of Hephæstus.

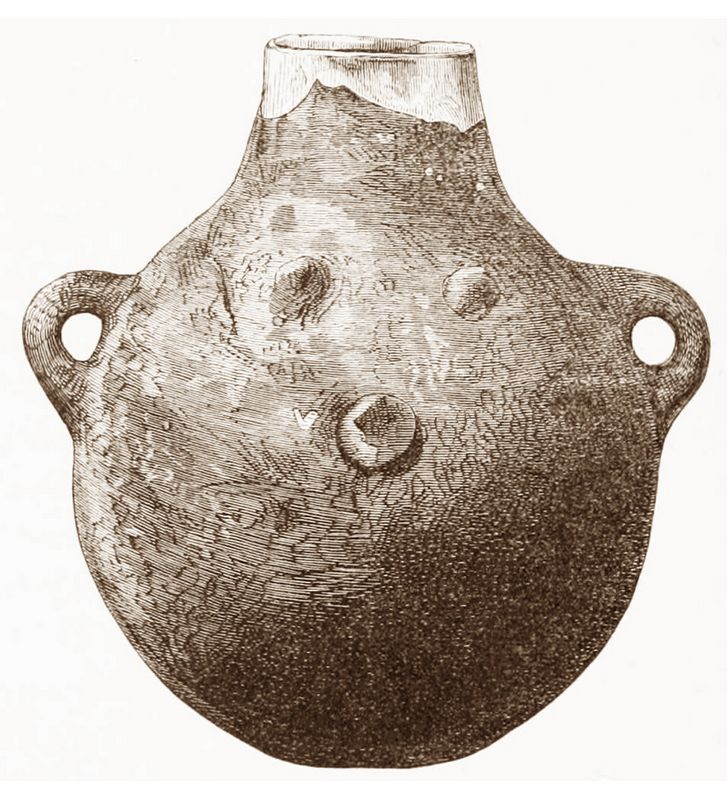

Fig.70: Large Terra-cotta Vase, with the Symbols of the Ilian Goddess (4m depth).

Footnotes:

[102] See the Frontispiece and Plan II.

[103] Gabriel de Mortillet, Le Signe de la Croix avant le Christianisme.

[104] Plates XXI. to LII. at the end of the volume.

[105] Copied in the Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, Organ der Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie und Urgeschichte, 1871, Heft III.

[106] Émile Burnouf, La Science des Religions.

[107] A. W. Franks, Horæ ferales, pl. 30, fig. 19.

[108]

The cut, for which we are indebted to Mr. Fergusson, represents the

foot-print of Buddha, as carved on the Amraverti Tope, near the river

Kistna. Besides the suastika, repeated again and again on the heels,

the cushions, and the toes, it bears the emblem of the mystic rose,

likewise frequently repeated (comp. the lithographed whorls, Nos. 330,

339, &c.), and the central circles show a close resemblance to some

of the Trojan whorls.—[Ed.]

[Continue to Chapter 7]

|

|