|

Chapter 7:

On the Hill of Hissarlik, April 25th, 1872.

SINCE

my report of the 5th of this month I have continued the excavations

most industriously with an average of 120 workmen. Unfortunately,

however, seven of these twenty days were lost through rainy weather and

festivals, one day also by a mutiny among my men. I had observed that

the smoking of cigarettes interrupted the work, and I therefore forbad

smoking during working hours, but I did not gain my point immediately,

for I found that the men smoked in secret. I was, however, determined

to carry my point, and caused it to be proclaimed that transgressors

would be forthwith dismissed and never taken on again. Enraged at this,

the workmen from the village of Renkoï—about 70 in number—declared that

they would not work, if everyone were not allowed to smoke as much as

he pleased; they left the platform, and deterred the men from the other

villages from working by throwing stones.

The good people had

imagined that I would give in to them at once, as I could not do

without them, and that{108} now I could not obtain workmen enough; that

moreover during the beautiful weather it was not likely that I would

sit still a whole day. But they found themselves mistaken, for I

immediately sent my foreman to the other neighbouring villages and

succeeded (to the horror of the 70 Renkoïts, who had waited the whole

night at my door) in collecting 120 workmen for the next morning

without requiring their services. My energetic measures have at last

completely humbled the Renkoïts, from whose impudence I had very much

to put up with during my last year’s excavations, and have also had a

beneficial effect upon all of my present men. Since the mutiny I have

not only been able to prohibit smoking, but even to lengthen the day’s

work by one hour; for, instead of working as formerly from half-past

five in the morning to half-past five in the evening, I now always

commence at five and continue till six in the evening. But, as before,

I allow half an hour at nine and an hour and a half in the afternoon

for eating and smoking.

According to an exact calculation of the

engineer, M. A. Laurent, in the seventeen days since the 1st of the

month I have removed about 8500 cubic meters (11,000 cubic yards) of

débris; this is about 666 cubic yards each day, and somewhat above

5-1/3 cubic yards each workman.

We have already advanced the

platform 49 feet into the hill, but to my extreme surprise I have not

yet reached the primary soil. The opinion I expressed in my report of

the 24th of November of last year, that the thickness of the hill on

the north side had not increased since the remotest times, I find

confirmed as regards the whole western end of my platform, to a breadth

of 45 meters (147½ feet); for it is only upon the eastern portion of

it, to a breadth of 82 feet, that I found 6½ and even 10 feet of soil;

below and behind it, as far as 16½ feet above the platform, there is

débris as hard as stone, which appears to consist only of ashes of wood

and animals,{109} the remains of the offerings presented to the Ilian

Athena. I therefore feel perfectly convinced that by penetrating

further into this part I shall come upon the site of the very ancient

temple of the goddess.

The ashes of this stratum have such a

clayey appearance, that I should believe it to be the pure earth, were

it not that I find it frequently to contain bones, charcoal, and small

shells, occasionally also small pieces of brick. The shells are

uninjured, which sufficiently proves that they cannot have been exposed

to heat. In this very hard stratum of ash, at 11 feet above the

platform, and 46 feet from its edge, I found a channel made of green

sandstone nearly 8 inches broad and above 7 inches high, which probably

once served for carrying away the blood of the animals sacrificed, and

must necessarily at one time have discharged its contents down the

declivity of the hill. It therefore proves that the thickness of the

hill at this point has increased fully 46 feet since the destruction of

the temple to which it belonged.

Fig.71: A Mould of Mica-schist for casting Ornaments (14m depth).

Upon

the other 147½ feet of the platform I find everywhere, as far as to

about 16½ feet high, colossal masses of large blocks of shelly

limestone, often more or less hewn, but generally unhewn, which

frequently lie so close one upon another that they have the appearance

of actual walls. But I soon found that all of these masses of stone

must of necessity belong to grand buildings which once have stood there

and were destroyed by a fearful catastrophe. The buildings cannot

possibly have been built of these stones without some uniting

substance, and I presume that this was done with mere earth, for I find

no trace of lime or cement. Between the immense masses of stone there

are intermediate spaces, more or less large, consisting of very firm

débris, often as hard as stone, in which we meet with very many bones,

shells, and quantities of other remains of habitation. No traces of any

kind of interesting articles were found in the whole length of the wall

of débris, 229½ feet in length{110} and 16¼ feet in height, except a

small splendidly worked hair-or dress-pin of silver, but destroyed by

rust.

To-day, however, at a perpendicular depth of 14 meters (46 feet)

I found a beautiful polished piece of mica-schist, with moulds for

casting two breast-pins (fig.71), and two other ornaments which are quite

unknown to me—all of the most fanciful description.

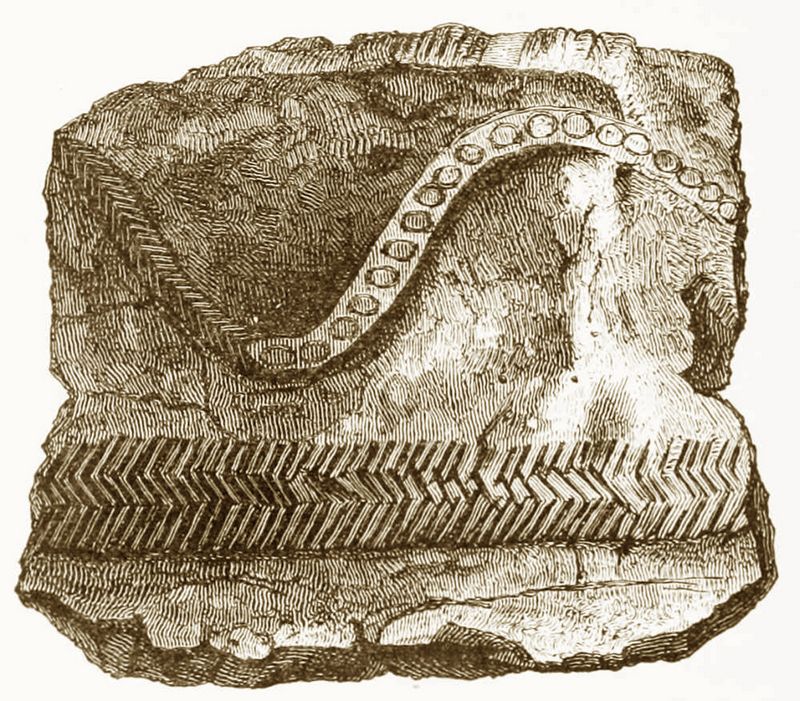

Fig.72: Fragment of a large Urn of Terra-cotta with Assyrian (?) Decorations, from the Lowest Stratum (14m depth).

The

fragments of this vase {111} show a thickness of about ¾ of an inch. Two

other enormous urns, but completely broken, either for water, wine, or

funereal ashes, with decorations in the form of several wreaths,

forming perfect circles, were found on the 22nd and 23rd of this month,

at from 19½ to 23 feet above the platform, and therefore, at a

perpendicular depth of from 26 to 33 feet. Both must have been more

than 6½ feet high, and more than 3¼ feet in diameter, for the fragments

show a thickness of nearly 2 inches. The wreaths are likewise in

bas-relief, and show either double triangles fitting into one another

with circles, or flowers, or three rows or sometimes one row of

circles. The last decoration was also found upon the frieze of green

stone which Lord Elgin discovered in the year 1810 in the treasury of

Agamemnon in Mycenæ, and which is now in the British Museum. Both this

frieze, and the above-mentioned urns discovered by me in the depths of

Ilium, distinctly point to Assyrian art, and I cannot look at them

without a feeling of sadness when I think with what tears of joy and

with what delight the ever-memorable German scholar, Julius Braun, who

unfortunately succumbed three years ago to his excessive exertions,

would have welcomed their discovery; for he was not only the great

advocate of the theory that the Homeric Troy must be only looked for

below the ruins of Ilium, but he was also the able defender of the

doctrine, that the plastic arts and a portion of the Egyptian and

Assyrian mythology had migrated to Asia Minor and Greece, and he has

shown this by thousands of irrefutable proofs in his profound and

excellent work, Geschichte der Kunst in ihrem Entwickelungsgange, which

I most urgently recommend to all who are interested in art and

archæology.

Both the urns found at a depth of 46 feet and those

at from 26 to 33 feet, as well as all the funereal urns and large wine

or water vessels which I formerly discovered, were standing upright,

which sufficiently proves that the colossal masses of débris and ruins

were gradually formed on the{112} spot, and could not have been brought

there from another place in order to increase the height of the hill.

This is, moreover, a pure impossibility in regard to the immense

numbers of gigantic blocks of stone, hewn and unhewn, which frequently

weigh from 1 to 2 tons.

In the strata at a depth of from 7 to 10

meters (23 to 33 feet), I found two lumps of lead of a round and

concave form, each weighing about two pounds; a great number of rusted

copper nails, also some knives and a copper lance; further very many

smaller and larger knives of white and brown silex in the form of

single and double-edged saws; a number of whet-stones of green and

black slate with a hole at one end, as well as various small objects of

ivory.[109] In all the strata from 4 to 10 meters (13 to 33 feet) deep

I found a number of hammers, axes and wedges of diorite, which,

however, are decidedly of much better workmanship in the strata below

the depth of 7 meters (23 feet) than in the upper ones. Likewise at all

depths from 3 meters (10 feet) below the surface we find a number of

flat idols of very fine marble; upon many of them is the owl’s face and

a female girdle with dots; upon one there are in addition two female

breasts.[110] The striking resemblance of these owls’ faces to those

upon many of the vases and covers, with a kind of helmet on the owl’s

head, makes me firmly convinced that all of the idols, and all of the

helmeted owls’ heads represent a goddess, and indeed must represent one

and the same goddess, all the more so as, in fact, all the owl-faced

vases with female breasts and a navel have also generally two upraised

arms: in one case the navel is represented by a cross with four

nails.[111] The cups (covers) with owls’ heads, on the other{113} hand,

never have breasts or a navel, yet upon some of them I find long female

hair represented at the back.[112]

The important question now

presents itself:—What goddess is it who is here found so repeatedly,

and is, moreover, the only one to be found, upon the idols,

drinking-cups and vases? The answer is:—She must necessarily be the

tutelary goddess of Troy, she must be the Ilian Athena, and this indeed

perfectly agrees with the statement of Homer, who continually calls her

?e? ??a???p?? ?????, “the goddess Athena with the owl’s face.” For the

epithet “??a???p??” has been wrongly translated by the scholars of all

ages, because they could not imagine that Athena should have been

represented with an owl’s face. The epithet, however, consists of the

two words ??a?? and ?p?, and, as I can show by an immense number of

proofs, the only possible literal translation is “with an owl’s face”;

and the usual translation “with blue, fiery or sparkling eyes” is

utterly wrong. The natural conclusion is that owing to progressive

civilization Athena received a human face, and her former owl’s head

was transformed into her favourite bird, the owl, which as such is

unknown to Homer. The next conclusion is that the worship of Athena as

the tutelary goddess of Troy was well known to Homer; hence that a Troy

existed, and that it was situated on the sacred spot, the depths of

which I am investigating.

In like manner, when excavations shall

be made in the Heræum between Argos and Mycenæ, and on the site of the

very ancient temple of Hera on the island of Samos, the image of this

goddess with a cow’s head will doubtless be found upon idols, cups and

vases; for “ß??p??” the usual epithet of Hera in Homer, can originally

have{114} signified nothing else than “with the face of an ox.” But as

Homer also sometimes applies the epithet ß??p?? to mortal women, it is

probable that even at his time it was considered to be bad taste to

represent Hera, the wife of the mightiest of all the gods, with the

face of an ox, and that therefore men even at that time began to

represent her with a woman’s face, but with the eyes of an ox, that is,

with very large eyes; consequently the common epithet of ß??p??, which

had formerly been only applied to Hera with the meaning of “with the

face of an ox,” now merely signified with large eyes.

Of

pottery we have found a great deal during the last weeks, but

unfortunately more than half of it in a broken condition. Of painting

upon terra-cotta there is still no trace; most of the vessels are of a

simple brilliant black, yellow, or brown colour; the very large vases

on the other hand are generally colourless. Plates of ordinary

manufacture I have as yet found only at a depth of from 8 to 10 meters

(26 to 33 feet), and, as can be distinctly seen (fig.73), they have been turned

upon a potter’s wheel (fig.73).

All the other vessels hitherto found seem,

however, to have been formed by the hand alone; yet they possess a

certain elegance, and excite the admiration of beholders by their

strange and very curious forms. The vases with a long neck bent back, a

beak-shaped mouth turned upwards, and a round protruding body[113]—two

of which are in the British{115} Museum, several of those found in

Cyprus in the Museum in Constantinople, and several of those discovered

beneath three layers of volcanic ashes in Thera and Therassia in the

French school in Athens—are almost certainly intended to represent

women, for I find the same here at a depth of from 26 to 33 feet, with

two or even with three breasts, and hence I believe that those found

here represent the tutelary goddess of Ilium.

We also find some vases

and covers with men’s faces (fig.74), which, however, are never without some

indications of the owl; moreover, the vases with such faces always have

two female breasts and a navel. I must draw especial attention to the

fact that almost all of the vases with owls’ faces, or with human faces

and the indications of the owl, have two uplifted arms, which serve as

handles, and this leads me to conjecture that they are imitations of

the large idol which was placed in the very ancient temple of the Ilian

divinity, which therefore must have had an owl’s face, but a female

figure, and two arms beside the head. It is very remarkable that most

of the vessels which I find have been suspended by cords, as is proved

by the two holes in the mouth, and the two little tubes, or holes in

the handles, at the side of the vessels.

Unfortunately,

many of the terra-cottas get broken when the débris is being loosened

and falls down, for there is only one way in which I can save my men

and myself from being crushed and maimed by the falling stones: this

is, by keeping the lowest part of the mighty earthen wall on the

perpendicular up to 16 feet (not 7 feet, as on the first five days),

and the whole of the upper part at an angle of 50 degrees, by always

loosening the perpendicular portion, by making shafts, and working with

large iron levers in pieces of from 15 to 30 cubic metres (20 to 40

cubic{116} yards).

By thus causing the débris and the stones of the

upper portion to be loosened with the pickaxe, the stones fall in

almost a direct line over the lower perpendicular wall of 16 feet;

therefore they roll at most a few paces, and there is less danger that

anyone will be hurt. By this means I also have the advantage that the

greatest portion of the débris falls down of its own accord, and what

remains can be shovelled down with little trouble, whereas at first I

spent half of my time in getting it down.

As, however, in making shafts

and in bringing down the colossal lumps of earth a certain amount of

skill and caution is necessary, I have engaged a third foreman at 7

francs a day, Georgios Photidos, of Paxos, who has for seven years

worked as a miner in Australia, and was there occupied principally in

making tunnels. Home-sickness led him back to his native country,

where, without having sufficient means of earning his daily bread, he,

in youthful thoughtlessness and out of patriotism, married a poor girl

of his own people who was but fifteen years old. It was only after his

marriage, and in consequence of domestic cares, that he recovered his

senses. He heard that I was making excavations here, and came on

speculation to offer me his services. As he had assured me, when I

first saw him, that my accepting his services was a question of life

and death to him and his wife, I engaged him at once, the more so

because I was very much in want of a miner, tunnel-maker, and pitman,

such as he is. Besides acting in these capacities, he is of great use

to me on Sundays and on other festivals, for he can write Greek, and he

is thus able to copy my Greek reports for the newspapers and learned

societies in the East; for I had hitherto found nothing more

intolerable than to have to write out in Greek three times over my long

reports about one and the same subject, especially as I had to take the

time from my sleep. To my great regret, the excellent engineer Adolphe

Laurent leaves me to-morrow, for his month is up, and he has now{117}

to commence the construction of the railroad from the Piræus to Lamia.

He has, however, made me a good plan of this hill.

I must add that the

Pergamus of Priam cannot have been limited to this hill, which is, for

the most part, artificial; but that, as I endeavoured to explain four

years ago,[114] it must necessarily have extended a good way further

south, beyond the high plateau. But even if the Pergamus should have

been confined to this hill, it was, nevertheless, larger than the

Acropolis of Athens; for the latter covers only 50,126 square meters

(about 60,000 square yards), whereas the plateau of this hill amounts

to 64,500 square meters (about 77,400 square yards). I must further

mention that, according to Laurent’s calculation, the plateau rises 46

feet above my platform, and that his measurements of its height (about

38 feet on the north and 39 feet on the south) applies to those points

where the steep precipice commences. I have just built a house with

three rooms, as well as a magazine and kitchen, which altogether cost

only 1000 francs (40l.), including the covering of waterproof felt; for

wood is cheap here, and a plank of about 10 feet in length, 10 inches

in breadth, and 1 inch thick, may be got for 2 piasters, or 40

centimes. (These houses are seen in Plates X. and XI.)

We still

find poisonous snakes among the stones as far down as from 33 to 36

feet, and I had hitherto been astonished to see my workmen take hold of

the reptiles with their hands and play with them; nay, yesterday I saw

one of the men bitten twice by a viper, without seeming to trouble

himself about it. When I expressed my horror, he laughed, and said that

he and all his comrades knew that there were a great many snakes in

this hill, and they had therefore all drunk a decoction of the

snake-weed which{118} grows in the district, and which renders the bite

harmless. Of course I ordered a decoction to be brought to me, so that

I also may be safe from their bites. I should, however, like to know

whether this decoction would be a safeguard against the fatal effects

of the bite of the hooded cobra, of which in India I have seen a man

die within half an hour; if it were so, it would be a good speculation

to cultivate snake-weed in India.

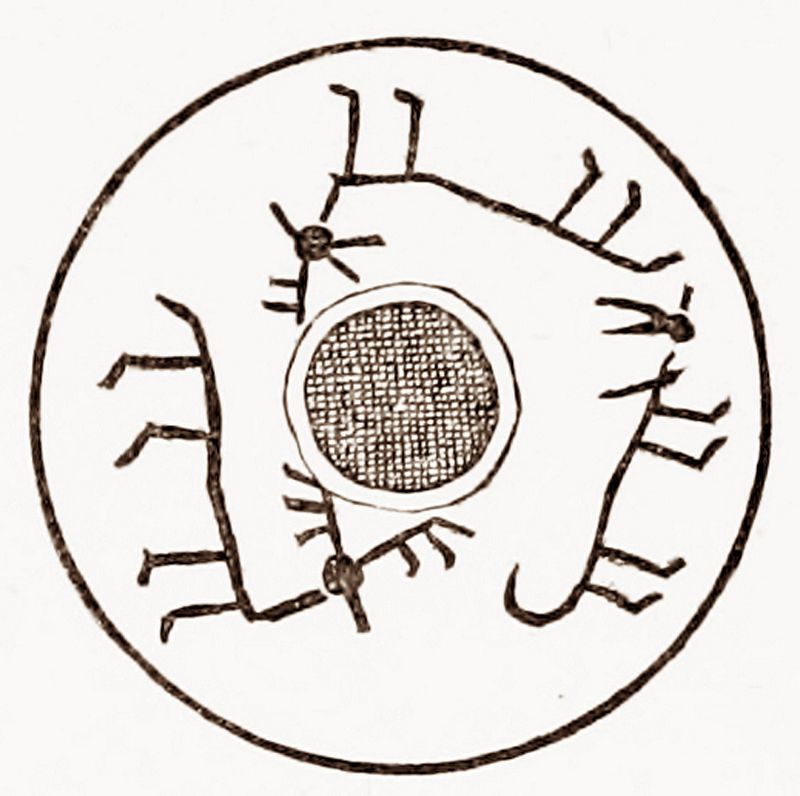

The frequently-discussed

terra-cottas in the form of the volcano and top (carrousel) are

continually found in immense numbers, as far as a depth of from 33 to

36 feet, and most of them have decorations, of which I always make an

accurate drawing.[115] On comparing these drawings, I now find that

all, without exception, represent the sun in the centre, and that

almost the half of the other carvings show either only simple rays or

rays with stars between, or round the edge; or again, three, four, six,

or eight simple, double, treble, and quadruple rising suns in a circle

round the edge.[116]

Sometimes the sun is in the centre of the cross

with four nails, which, according to the explanations in my sixth

memoir, can evidently, and in all cases, represent only the instrument

which our Aryan forefathers used for producing the holy fire (Agni),

and which some Sanscrit scholars call “Arani” and others “Suastika.”

The rising sun must have been the most sacred object to our Aryan

ancestors; for, according to Max Müller (Essays), out of it—that is,

out of its struggle with the clouds—arose a very large portion of the

gods who afterwards peopled Olympus. Upon some pieces the sun is

surrounded by 40 or 50 little stars.

I also found one upon which it is

represented{119} in the centre, surrounded by 32 little stars and three

?; another where one entire half of the circle is filled by the rays of

the sun, which, as in all cases, occupies the central point; on the

other half are two ? and 18 little stars, of which twice three (like

the sword of Orion) stand in a row; and another where even four are

seen in a row. As M. Émile Burnouf tells me, three dots in a row, in

the Persian cuneiform inscriptions, denote “royal majesty.”

I do not

venture to decide whether the three dots here admit of a similar

interpretation. Perhaps they point to the majesty of the sun-god and of

Agni, who was produced out of the ?. Upon some of these terra-cottas

the sun is even surrounded by four ?, which again form a cross by their

position round it. Upon others, again, I find the sun in the centre of

a cross formed by four trees, and each one of these trees has three or

four large leaves.[117] Indian scholars will, perhaps, find these

tree-crosses to represent the framework upon which our ancestors used

to produce the holy fire, and the repeatedly-recurring fifth tree to be

the “Pramantha.”

I find representations of this same tree several

times, either surrounded by circles or standing alone, upon small

terra-cotta cones of from 1½ to 2-1/3 inches in diameter, which, in

addition, have the most various kinds of symbols and a number of suns

and stars. Upon a ball, found at the depth of 8 meters (26 feet), there

is a tree of this kind, surrounded by stars, opposite a ?, beside which

there is a group of nine little stars.[118] I therefore venture to

express the conjecture that this tree is the tree of life, which is so

frequently met with in the Assyrian sculptures, and that it is

identical with the holy Sôma-tree, which, according to the Vêdas (see

Émile Burnouf, Max Müller, Adalbert Kuhn, and Fr. Windischmann), grows

in{120} heaven, and is there guarded by the Gandharvas, who belong to

the primeval Aryan period, and subsequently became the Centaurs of the

Greeks.

Indra, the sun-god, in the form of a falcon,[119] stole from

heaven this Sôma-tree, from which trickled the Amrita (ambrosia) which

conferred immortality. Fr. Windischmann[120] has pointed out the

existence of the Sôma-tree worship as common to the tribes of Aryans

before their separation, and he therefore justly designates it an

inheritance from their most ancient traditions.[121]

Julius Braun[122]

says, in regard to this Sôma-tree: “Hermes, the rare visitor, is

regaled with nectar and ambrosia. This is the food which the gods

require in order to preserve their immortality. It has come to the West

from Central Asia, with the whole company of the Olympian gods; for the

root of this conception is the tree of life in the ancient system of

Zoroaster. The fruit and sap of this tree of life bestows immortality,

and the future Messiah (Sosiosh, in the Zend writings) will give some

of it to all the faithful and make them all immortal. This hope we have

seen fully expressed in the Assyrian sculptures, where the winged genii

stand before the holy tree with a vessel containing the juice and

fruit.”

Just now two of those curious little terra-cottas, in

the form of a volcano, were brought to me, upon one of which three

animals with antlers are engraved in a circle round the sun;[123] upon

another there are four signs (which I have hitherto not met with) in

the shape of large combs with{121} long teeth, forming a cross round

the sun.[124] I conjecture that these extremely remarkable

hieroglyphics, which at first sight might be imagined to be actual

letters, can by no means represent anything else than the sacrificial

altar with the flames blazing upon it. I do not doubt moreover, that in

the continuation of the excavations I shall find this comb-shaped sign

together with other symbols, which will confirm my conjectures.

Fig.75: A Whorl, with three animals (3m depth).

I

must also add that the good old Trojans may perhaps have brought with

them from Bactria the name of Ida, which they gave to the mountain

which I see before me to the south-east, covered with snow, upon which

Jove and Hera held dalliance,[125] and from which Jove looked down upon

Ilium and upon the battles in the Plain of Troy, for, according to Max

Müller,[126] Ida was the wife of Dyaus (Zeus), and their son was Eros.

The parents whom Sappho ascribes to Eros—Heaven and Earth—are identical

with his Vedic parents. Heracles is called ?da???, from his being

identical with the Sun, and he has this name in common with Apollo and

Jove.

Fig.75b: Two Whorls,

To-morrow the Greek Easter festival commences, during

which unfortunately there are six days on which no work is done. Thus I

shall not be able to continue the excavations until the 1st of May.{122}

Footnotes:

[109]

See an illustration to Chapter X. for similar ivories, still more

interesting, from their greater depth, than those mentioned in the

text, which are very imperfectly shown on the original photograph.

[110] See the Plate of Idols, p. 36.

[111] See Cut, No. 13, p. 35.

[112]

Dr. Schliemann is here speaking of the “cups” which he afterwards

decided to be covers, which of course represent only the head, the body

being on the vase.—[Ed.]

[113] See Cut, No. 54, p. 86.

[114]

Ithaque, le Péloponnèse et Troie. Dr. Schliemann’s subsequent change of

opinion on this point is explained in subsequent chapters, and in the

Introduction.

[115] The various types of whorls spoken of here

and throughout the work are delineated in the lithographic Plates at

the end of the volume, and are described in the List of Illustrations.

[116]

These “rising suns” are the arcs with their ends resting on the

circumference of the whorl, as in Nos. 321-28, and many others on the

Plates. M. Burnouf describes them as “stations of the sun.”

[117]

For the type of whorls with “sôma-trees” or “trees of life” (four, or

more, or fewer), see Nos. 398, 400, 401, 404, &c. In No. 410 the

four trees form a cross.

[118] Plate LII., No. 498.

[119]

This falcon seems to be represented by rude two-legged figures on some

of the whorls:—e. g. on Plate XLV., No. 468 (comp. p. 135).

[120] Abhandlungen der K. bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1846, S. 127.

[121] A. Kuhn, ‘Herabkunft des Feuers.'

[122] Geschichte der Kunst.

[123]

See the cut No. 75 and also on Plate XXX., No. 382. M. Burnouf

describes the animal to the right as a hare, the symbol of the Moon,

and the other two as the antelopes, which denote the prevailing of the

two halves of the month (quinzaines).

[124] See Plate XXXV., No. 414. The same symbol is seen on several other examples.

[125]

Iliad, XIV. 346-351. An English writer ought surely to use our

old-fashioned form Jove, which is also even philologically preferable

as the stem common to Ζεύς and Ju-piter (Διο = Ζεϝ = Jov), rather than

the somewhat pedantically sounding Ζεύς.—[Ed.]

[126] Essays, II. 93.

[Continue to Chapter 8]

|

|