|

Introduction (part C).

The town of Ilium, upon

whose site I have been digging for more than three years, boasted

itself to be the successor of Troy; and as throughout antiquity the

belief in the identity of its site with that of the ancient city of

Priam was firmly established and not doubted by anyone, it is clear

that the whole course of tradition confirms this identity. At last

Strabo lifted up his voice against it; though, as he himself admits, he

had never visited the Plain of Troy, and he trusted to the accounts of

Demetrius of Scepsis, which were suggested by vanity. According to

Strabo,[61] this Demetrius maintained that his native town of Scepsis

had been the residence of Æneas, and he envied Ilium the honour of

having been the{42} metropolis of the Trojan kingdom.

Table 1: Diagram showing the successive strata of remains on the hill of Hissarlik.

He therefore put

forward the following view of the case:—that Ilium and its environs did

not contain space enough for the great deeds of the Iliad; that the

whole plain which separated the city from the sea was alluvial land,

and that it was not formed until after the time of the Trojan war. As

another proof that the locality of the two cities could not be the

same, he adds that Achilles and Hector ran three times round Troy,

whereas one could not run round Ilium on account of the continuous

mountain ridge (d?? t?? s??e?? ?????). For all of these reasons he says

that ancient Troy must be placed on the site of the “Village of the

Ilians” (?????? ??µ?), 30 stadia or 3 geographical miles from Ilium and

42 stadia from the coast, although he is obliged to admit that not the

faintest trace of the city has been preserved.[62]

Fig.31b: Three Tablets of terracotta, from the ruins of Greek Ilium (1-2m. depth).

Strabo, with

his peculiarly correct judgment, would assuredly have rejected all

these erroneous assertions of Demetrius of Scepsis, had he himself

visited the Plain of Troy, for they can easily be refuted.

I

have to remark that it is quite easy to run round the site of Troy;

further, that the distance from Ilium to the coast, in a straight line,

is about 4 miles, while the distance in a straight line north-west to

the promontory of Sigeum (and at this place tradition, as late as

Strabo’s time, fixed the site of the Greek encampment) amounts to about

4½ miles. For Strabo says:[63] “Next to Rhœteum may be seen the ruined

town of Sigeum, the port of the Achæans, the Achæan camp, and the marsh

or lake called Stomalimne, and the mouth of the Scamander.”

In

November, 1871, I made excavations upon the site of the “?????? ??µ?,”

the results of which completely refute the theory of Demetrius of

Scepsis; for I found everywhere{43} the primary soil at a depth of less

than a foot and a half; and the continuous ridge on the one side of the

site, which appeared to contain the ruins of a large town-wall,

consisted of nothing but pure granulated earth, without any admixture

of ruins.

In the year 1788, Lechevalier visited the plain of

Troy, and was so enthusiastically in favour of the theory that the site

of Homer’s Troy was to be found at the village of Bunarbashi and the

heights behind it, that he disdained to investigate the site of Ilium:

this is evident from his work ‘Voyage de la Troade’ (3e éd., Paris,

1802) and from the accompanying map, in which he most absurdly calls

this very ancient town “Ilium Novum,” and transposes it to the other

side of the Scamander, beside Kumkaleh, close to the sea and about 4

miles from its true position. This theory, that the site of Troy can

only be looked for in the village of Bunarbashi and upon the heights

behind it, was likewise maintained by the following scholars: by

Rennell, ‘Observations on the Topography of the Plain of Troy’ (London,

1814); by P. W. Forchhammer in the ‘Journal of the Royal Geographical

Society,’ vol. xii., 1842; by Mauduit, ‘Découvertes dans la Troade’

(Paris et Londres, 1840); by Welcker, ‘Kleine Schriften;’ by Texier; by

Choiseul-Gouffrier, ‘Voyage Pittoresque de la Grèce’ (1820); by M. G.

Nikolaïdes (Paris, 1867); and by Ernst Curtius in his lecture delivered

at Berlin in November, 1871, after his journey to the Troad and

Ephesus, whither he was accompanied by Professors Adler and Müllenhof,

and by Dr. Hirschfeldt.

But, as I have explained in detail in my work,

‘Ithaque, le Péloponnèse et Troie’ (Paris, 1869), this theory is in

every respect in direct opposition to all the statements of the Iliad.

My excavations at Bunarbashi prove, moreover, that no town can ever

have stood there; for I find everywhere the pure virgin soil at a depth

of less than 5 feet, and generally immediately below the surface. I

have likewise proved, by my excavations on{44} the heights behind this

village, that human dwellings can never have existed there; for I found

the native rock nowhere at a greater depth than a foot and a half. This

is further confirmed by the sometimes pointed, sometimes abrupt, and

always anomalous form of the rocks which are seen wherever they are not

covered with earth.

At half-an-hour’s distance behind Bunarbashi there

is, it is true, the site of quite a small town, encircled on two sides

by precipices and on the other by the ruins of a surrounding wall,

which town I formerly considered to be Scamandria; but one of the

inscriptions found in the ruins of the temple of Athena in the Ilium of

the Greek colony makes me now believe with certainty that the spot

above Bunarbashi is not the site of Scamandria, but of Gergis.

Moreover, the accumulation of débris there is extremely insignificant,

and the naked rock protrudes not only in the small Acropolis, but also

in very many places of the site of the little town. Further, in all

cases where there is an accumulation of débris, I found fragments of

Hellenic pottery, and of Hellenic pottery only, down to the primary

soil. As archæology cannot allow the most ancient of these fragments to

be any older than from 500 to 600 years before Christ, the walls of the

small town—which used to be regarded as of the same age as those of

Mycenæ—can certainly be no older than 500 to 600 B.C. at most.

Immediately

below this little town there are three tombs of heroes, one of which

has been assigned to Priam, another to Hector, because it was built

entirely of small stones. The latter grave was laid open in October

1872, by Sir John Lubbock, who found it to contain nothing but painted

fragments of Hellenic pottery to which the highest date that can be

assigned is 300 B.C.; and these fragments tell us the age of the tomb

likewise.

The late Consul J. G. von Hahn, who in May 1864, in

his extensive excavations of the acropolis of Gergis{45} down to the

primary soil, only discovered the same, and nothing but exactly the

same, fragments of Hellenic pottery as I found there in my small

excavations, writes in his pamphlet, ‘Die Ausgrabungen des Homerischen

Pergamos:’ “In spite of the diligent search which my companions and I

made on the extensive northern slope of the Balidagh, from the foot of

the acropolis (of Gergis) to the springs of Bunarbashi, we could not

discover any indication beyond the three heroic tombs, that might have

pointed to a former human settlement, not even antique fragments of

pottery and pieces of brick,—those never-failing, and consequently

imperishable, proofs of an ancient settlement. No pillars or other

masonry, no ancient square stones, no quarry in the natural rock, no

artificial levelling of the rock; on all sides the earth was in its

natural state and had not been touched by human hands.”

The

erroneous theory which assigns Troy to the heights of Bunarbashi could,

in fact, never have gained ground, had its above-named advocates

employed the few hours which they spent on the heights, and in

Bunarbashi itself, in making small holes, with the aid of even a single

workman.

Clarke and Barker Webb (Paris, 1844) maintained that

Troy was situated on the hills of Chiplak. But unfortunately they also

had not given themselves the trouble to make excavations there;

otherwise they would have convinced themselves, with but very little

trouble, that all the hills in and around Chiplak, as far as the

surrounding Wall of Ilium, contain only the pure native soil.

H.

N. Ulrichs[64] maintains that Troy was situated on the hills of

Atzik-Kioï, which in my map I have called Eski Akshi köi. But I have

examined these hills also, and found that they consist of the pure

native soil. I used a spade in making these excavations, but a

pocket-knife would have answered the purpose.{46}

I cannot

conceive how it is possible that the solution of the great problem,

“ubi Troja fuit”—which is surely one of the greatest interest to the

whole civilized world—should have been treated so superficially that,

after a few hours’ visit to the Plain of Troy, men have sat down at

home and written voluminous works to defend a theory, the worthlessness

of which they would have perceived had they but made excavations for a

single hour.

I am rejoiced that I can mention with praise Dr.

Wilhelm Buchner,[65] Dr. G. von Eckenbrecher,[66] and C. MacLaren,[67]

who, although they made no excavations, have nevertheless in their

excellent treatises proved by many irrefutable arguments that the site

of Ilium, where I have been digging for more than three years,

corresponds with all the statements of the Iliad in regard to the site

of Troy, and that the ancient city must be looked for there and nowhere

else.

It is also with gratitude that I think of the great German

scholar, who unfortunately succumbed five years ago to his unwearied

exertions, Julius Braun, the advocate of the theory that Homer’s Troy

was to be found only on the site of Ilium, in the depths of the hill of

HISSARLIK. I most strongly recommend his excellent work, ‘Die

Geschichte der Kunst in ihrem Entwickelungsgang,’ to all those who are

interested in whatever is true, beautiful and sublime.

Neither

can I do otherwise than gratefully mention my honoured friend, the

celebrated Sanscrit scholar and unwearied investigator Émile Burnouf,

the Director of the{47} French school in Athens, who personally, and

through his many excellent works, especially the one published last

year, ‘La Science des Religions,’ has given me several suggestions,

which have enabled me to decipher many of the Trojan symbols.[68]

It

is also with a feeling of gratitude that I think of my honoured friend,

the most learned Greek whom I have ever had the pleasure of knowing,

Professor Stephanos Kommanoudes, in Athens, who has supported me with

his most valuable advice whenever I was in need of it. In like manner I

here tender my cordial thanks to my honoured friend the Greek Consul of

the Dardanelles, G. Dokos, who showed me many kindnesses during my long

excavations.

I beg to draw especial attention to the fact that,

in the neighbourhood of Troy, several types of very ancient

pottery—like those found in my excavations at a depth of from 10 to 33

feet—have been preserved down to the present day. For instance, in the

crockery-shops on the shores of the Dardanelles there are immense

numbers of earthen vessels with long upright necks and the breasts of a

woman, and others

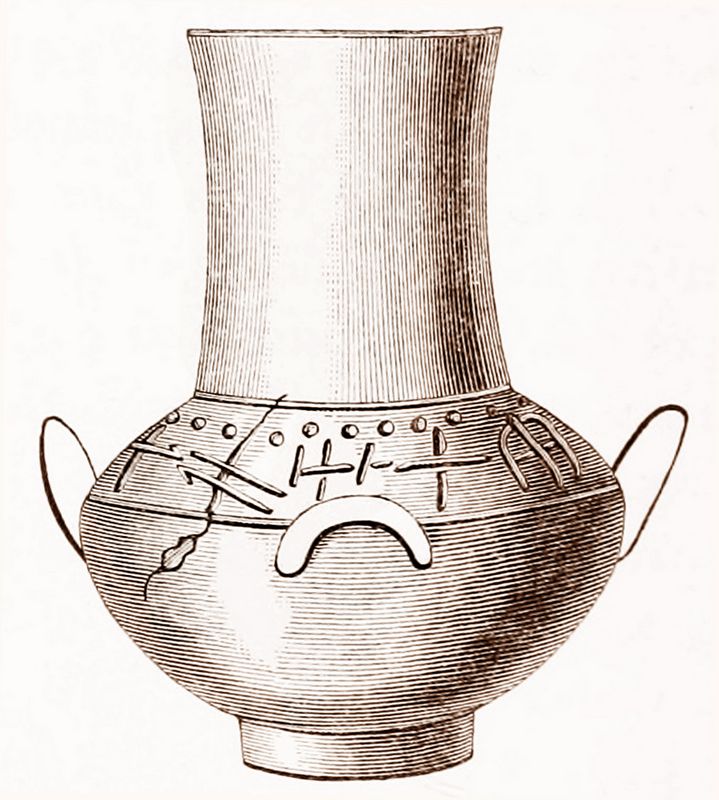

Fig.32: The largest of the Terra-cotta Vases found in the Royal Palace of Troy. Height 20 inches. The Cover was found near it.

After

long and mature deliberation, I have arrived at the firm conviction

that all of those vessels—met with here in great numbers at a depth of

from 10 to 33 feet, and{48} more especially in the Trojan layer of

débris, at a depth of from 23 to 33 feet—which have the exact shape of

a bell and a coronet beneath, so that they can only stand upon their

mouth, and which I have hitherto described as cups, must necessarily,

and perhaps even exclusively, have been used as lids to the numerous

terra-cotta vases with a smooth neck and on either side two ear-shaped

decorations, between which are two mighty wings, which, as they are

hollowed and taper away to a point, can never have served as handles,

the more so as between the ear-shaped decorations there is a small

handle on either side. Now, as the latter resembles an owl’s beak, and

especially as this is seen between the ear-shaped ornaments, it was

doubtless intended to represent the image of the owl with upraised

wings on each side of the vases, which image received a noble

appearance from the splendid lid with a coronet. I give a drawing of

the largest vase of this type (fig.32), which{49} was found a few days ago in

the royal palace at a depth of from 28 to 29½ feet; on the top of it I

have placed the bell-shaped lid with a coronet, which was discovered

close by and appears to have belonged to it.

My friend M.

Landerer, Professor of Chemistry in Athens, who has carefully examined

the colours of the Trojan antiquities, writes to me as follows:—“In the

first place, as to the vessels themselves, some have been turned upon a

potter’s wheel, some have been moulded by the hand. Their ground-colour

varies according to the nature of the clay. I find some of them made of

black, deep-brown, red, yellowish, and ashy-grey clay. All of these

kinds of clay, which the Trojan potters used for their ware, consist of

clay containing oxide of iron and silica (argile silicieuse

ferrugineuse), and, according to the stronger or weaker mode of

burning, the oxide of iron in the clay became more or less oxidised:

thus the black, brown, red, yellow, or grey colour is explained by the

oxidation of the iron. The beautiful black gloss of the vessels found

upon the native soil, at a depth of 46 feet, does not contain any oxide

of lead, but consists of coal-black (Kohlenschwarz),[69] which was

melted together with the clay and penetrated into its pores. This can

be explained by the clay vessels having been placed in slow furnaces in

which resino

Fig.33: Inscribed Trojan Vase of Terra-cotta (8½ m depth).

“The

white colour with which the engraved decorations of the Trojan

terra-cottas were filled, by means of a pointed instrument, is nothing

but pure white clay. In like manner, the painting on the potsherd given

above (figs.33,34) ,[70] is made with white clay, and with black clay containing

coal. The brilliant red colour of the large two-handled vessels (d?pa

?µf???pe??a)[71] is no peculiar colour, but merely oxide of iron, which

is a component part of the clay of which the cups were made. Many of

the brilliant yellow Trojan vessels, I find, are made of grey clay, and

painted over with a mass of yellow clay containing oxide of iron; they

were then polished with one of those sharp pieces of diorite which are

so frequently met with in Troy, and afterwards burnt.{51}

Fig.34: Inscription on the Vase in fig.33.

The

large marshes lying before the site of ?????? ??µ?, and discussed in my

second memoir, have long since been drained, and thus the estate of

Thymbria (formerly Batak) has acquired 240 acres of rich land. As might

have been expected, they were not found to contain any hot springs, but

only three springs of cold water.

n my twenty-second memoir I

have mentioned a Trojan vase, with a row of signs running round it,

which I considered to be symbolical, and therefore did not have them

specially reproduced by photography. However, as my learned friend

Émile Burnouf is of opinion that they form a real inscription in

Chinese letters,[72] I give them here according to his drawing.

M. Burnouf explains them as follows:—

and

adds: “Les caractères du petit vase ne sont ni grecs ni sanscrits, ni

phéniciens, ni, ni, ni—ils sont parfaitement lisibles en chinois!!! Ce

vase peut être venu en Troade de l’Asie septentrional, dont tout le

Nord était touranien.” Characters similar to those given above

frequently occur, more especially upon the perforated terra-cottas in

the form of volcanoes and tops.{52}

As the Turkish papers have

charged me in a shameful manner with having acted against the letter of

the firman granted to me, in having kept the Treasure for myself

instead of sharing it with the Turkish Government, I find myself

obliged to explain here, in a few words, how it is that I have the most

perfect right to that treasure. It was only in order to spare Safvet

Pacha, the late Minister of Public Instruction, that I stated in my

first memoir, that at my request, and in the interest of science, he

had arranged for the portion of Hissarlik, which belonged to the two

Turks in Kum-Kaleh, to be bought by the Government. But the true state

of the case is this. Since my excavations here in the beginning of

April 1870, I had made unceasing endeavours to buy this field, and at

last, after having travelled three times to Kum-Kaleh simply with this

object, I succeeded in beating the two proprietors down to the sum of

1000 francs (40l.) Then, in December 1870, I went to Safvet Pacha at

Constantinople, and told him that, after eight months’ vain endeavours,

I had at last succeeded in arranging for the purchase of the principal

site of Troy for 1000 francs, and that I should conclude the bargain as

soon as he would grant me permission to excavate the field. He knew

nothing about Troy or Homer; but I explained the matter to him briefly,

and said that I hoped to find there antiquities of immense value to

science. He, however, thought that I should find a great deal of gold,

and therefore wished me to give him all the details I could, and then

requested me to call again in eight days. When I returned to him, I

heard to my horror that he had already compelled the two proprietors to

sell him the field for 600 francs (24l.), and that I might make

excavations there if I wished, but that everything I found must be

given up to him. I told him in the plainest language what I thought of

his odious and contemptible conduct, and declared that I would have

nothing more to do with him, and that I should make no excavations.{53}

But

through Mr. Wyne McVeagh, at that time the American Consul, he

repeatedly offered to let me make excavations, on condition that I

should give him only one-half of the things found. At the persuasion of

that gentleman I accepted the offer, on condition that I should have

the right to carry away my half out of Turkey. But the right thus

conceded to me was revoked in April 1872, by a ministerial decree, in

which it was said that I was not to export any part of my share of the

discovered antiquities, but that I had the right to sell them in

Turkey. The Turkish Government, by this new decree, broke our written

contract in the fullest sense of the word, and I was released from

every obligation. Hence I no longer troubled myself in the slightest

degree about the contract which was broken without any fault on my

part. I kept everything valuable that I found for myself, and thus

saved it for science; and I feel sure that the whole civilized world

will approve of my having done so. The new-discovered Trojan

antiquities, and especially the Treasure, far surpass my most sanguine

expectations, and fully repay me for the contemptible trick which

Safvet Pacha played me, as well as for the continual and unpleasant

presence of a Turkish official during my excavations, to whom I was

forced to pay 4¾ francs a day.

It was by no means because I

considered it to be my duty, but simply to show my friendly intentions,

that I presented the Museum in Constantinople with seven large vases,

from 5 to 6½ feet in height, and with four sacks of stone implements. I

have thus become the only benefactor the Museum has ever had; for,

although all firmans are granted upon the express condition that

one-half of the discovered antiquities shall be given to the Museum,

yet it has hitherto never received an article from anyone. The reason

is that the Museum is anything but open to the public, and the sentry

frequently refuses admittance even to its Director, so everyone

knows{54} that the antiquities sent there would be for ever lost to

science.

The great Indian scholar, Max Müller of Oxford, has

just written to me in regard to the owl-headed tutelary divinity of

Troy. “Under all circumstances, the owl-headed idol cannot be made to

explain the idea of the goddess. The ideal conception and the naming of

the goddess came first; and in that name the owl’s head, whatever it

may mean, is figurative or ideal. In the idol the figurative intention

is forgotten, just as the sun is represented with a golden hand,

whereas the ideal conception of ‘golden-handed’ was ‘spreading his

golden rays.’ An owl-headed deity was most likely intended for a deity

of the morning or the dawn, the owl-light; to change it into a human

figure with an owl’s head was the work of a later and more

materializing age.”

I completely agree with this. But it is

evident from this that the Trojans, or at least the first settlers on

the hill, spoke Greek, for if they took the epithet of their goddess,

“??a???p??,” from the ideal conception which they formed of her and in

later times changed it into an owl-headed female figure, they must

necessarily have known that ??a?? meant owl, and ?p? face. That the

transformation took place many centuries, and probably more than 1000

years, before Homer’s time, is moreover proved by owls’ heads occurring

on the vases and even in the monograms in the lowest strata of the

predecessors of the Trojans, even at a depth of 46 feet.

I have

still to draw attention to the fact, that in looking over my Trojan

collection from a depth of 2 meters (6½ feet), I find 70 very pretty

brilliant black or red terra-cottas, with or without engraved

decorations, which, both in quality and form, have not the slightest

resemblance either to the Greek or to the pre-historic earthenware.

Thus it seems that just before the arrival of the Greek colony yet

another tribe inhabited this hill{55} for a short time.[73] These

pieces of earthenware may be recognised by the two long-pointed handles

of the large channelled cups, which also generally possess three or

four small horns.

Dr. Heinrich Schliemann.

Footnotes:

[61] XIII. i., p. 122, Tauchnitz edition.

[62] Strabo, XIII. i., p. 99. See the Map of the Plain of Troy.

[63] XIII. i., p. 103.

[64] ‘Rheinisches Museum,’ Neue Folge, III., s. 573-608.

[65] ‘Jahresbericht über das Gymnasium Fridericianum,’ Schwerin, 1871 und 1872.

[66] ‘Rheinisches Museum,’ Neue Folge, 2. Jahrg., s. 1 fg.

[67]

‘Dissertation on the Topography of the Trojan War.’ Edinburgh, 1822.

Second Edition. ‘The Plain of Troy described,’ &c. 1863. Dr.

Schliemann might have added the weighty authority of Mr. Grote,

‘History of Greece,’ vol. i., chap. xv.—[Ed.]

[68] Dr. Émile

Burnouf has published a very clear and interesting account of Dr.

Schliemann’s discoveries, in the ‘Revue des Deux Mondes’ for Jan. 1,

1874.—[Ed.]

[69] As we call it, lamp-black, that is, tolerably pure carbon.—[Ed.]

[70] See the Cut No. 1 on p. 15.

[71]

These are the vases so often mentioned as having the form of great

champagne glasses (see the Cuts on see p. 85, 158, 166, 171). Dr.

Schliemann also applies the name to the unique boat-shaped vessel of

pure gold found in the Treasure.—[Ed.]

[72] If M. Burnouf meant

this seriously at the time, it can now only stand as a curious

coincidence, interesting as one example of the tentative process of

this new enquiry. (See the Appendix.)—[Ed.]

[73] These

indications of a fifth pre-Hellenic settlement, if confirmed by further

investigation, would seem to point to the spread of the Lydians over

western Asia Minor.—Ed..

.

Continue to Chapter 1.

|

|