|

Chapter 1: Work at Hissarlik in 1871.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, in the Plain of Troy, October 18th, 1871.

IN my work Ithaca, the Peloponnesus, and Troy,

published in 1869, I endeavoured to prove, both by the result of my own

excavations and by the statements of the Iliad, that the Homeric Troy

cannot possibly have been situated on the heights of Bunarbashi, to

which place most archæologists assign it. At the same time I

endeavoured to explain that the site of Troy must necessarily be

identical with the site of that town which, throughout all antiquity

and down to its complete destruction at the end of the eighth or the

beginning of the ninth century A.D.,[74] was called Ilium, and not

until 1000 years after its disappearance—that is 1788 A.D.—was

christened Ilium Novum by Lechevalier,{58}[75] who, as his work proves,

can never have visited his Ilium Novum; for in his map he places it on

the other side of the Scamander, close to Kum-kaleh, and therefore 4

miles from its true position.

The site of Ilium is upon a

plateau lying on an average about 80 feet above the Plain, and

descending very abruptly on the north side. Its north-western corner is

formed by a hill about 26 feet higher still, which is about 705 feet in

breadth and 984 in length,[76] and from its imposing situation and

natural fortifications this hill of Hissarlik seems specially suited to

be the Acropolis of the town.[77] Ever since my first visit, I never

doubted that I should find the Pergamus of Priam in the depths of this

hill. In an excavation which I made on its north-western corner in

April 1870,[78] I found among other things, at a depth of 16 feet,

walls about 6½ feet thick, which, as has now been proved, belong to a

bastion of the time of Lysimachus.

Unfortunately I could not continue

those excavations at the time, because the proprietors of the field,

two Turks in Kum-Kaleh, who had their sheepfolds on the site, would

only grant me permission to dig further on condition that I would at

once pay them 12,000 piasters for damages,[79] and in addition they

wished to bind me, after the conclusion of my excavations, to put the

field in order again. As this did not suit my convenience, and the two

proprietors would not sell me the field at any price, I applied to his

Excellency Safvet Pacha, the Minister of Public Instruction, who at my

request, and in the interest of science, managed that Achmed Pacha, the

Governor of the Dardanelles and the Archipelago, should receive orders

from the Ministry of the Interior to have the field valued{59} by

competent persons, and to force the proprietors to sell it to the

Government at the price at which it had been valued: it was thus

obtained for 3000 piasters.

In trying to obtain the necessary

firman for continuing my excavations, I met with new and great

difficulties, for the Turkish Government are collecting ancient works

of art for their recently established Museum in Constantinople, in

consequence of which the Sultan no longer grants permission for making

excavations. But what I could not obtain in spite of three journeys to

Constantinople, I got at last through the intercession of my valued

friend, the temporary chargé d’affaires of the United States to the

Sublime Porte—Mr. John P. Brown, the author of the excellent work

‘Ancient and Modern Constantinople’ (London, 1868).

So on the

27th of September I arrived at the Dardanelles with my firman. But here

again I met with difficulties, this time on the part of the before

named Achmed Pacha, who imagined that the position of the field which I

was to excavate was not accurately enough indicated in the document,

and therefore would not give me his permission for the excavations

until he should receive a more definite explanation from the Grand

Vizier. Owing to the change of ministry which had occurred, a long time

would no doubt have elapsed before the matter was settled, had it not

occurred to Mr. Brown to apply to his Excellency Kiamil-Pacha, the new

Minister of Public Instruction, who takes a lively interest in science,

and at whose intercession the Grand Vizier immediately gave Achmed

Pacha the desired explanation. This, however, again occupied 13 days,

and it was only on the evening of the 10th of October that I started

with my wife from the Dardanelles for the Plain of Troy, a journey of

eight hours. As, according to the firman, I was to be watched by a

Turkish official, whose salary I have to pay during the time of my

excavations, Achmed Pacha assigned to me{60} the second secretary of

his chancellary of justice, an Armenian, by name Georgios Sarkis, whom

I pay 23 piasters daily.

At last, on Wednesday, the 11th of this

month, I again commenced my excavations with 8 workmen, but on the

following morning I was enabled to increase their number to 35, and on

the 13th to 74, each of whom receives 9 piasters daily (1 franc 80

centimes). As, unfortunately, I only brought 8 wheelbarrows from

France, and they cannot be obtained here, and cannot even be made in

all the country round, I have to use 52 baskets for carrying away the

rubbish. This work, however, proceeds but slowly and is very tiring, as

the rubbish has to be carried a long way off. I therefore employ also

four carts drawn by oxen, each of which again costs me 20 piasters a

day. I work with great energy and spare no cost, in order, if possible,

to reach the native soil before the winter rains set in, which may

happen at any moment. Thus I hope finally to solve the great problem as

to whether the hill of Hissarlik is—as I firmly believe—the citadel of

Troy.

As it is an established fact that hills which consist of

pure earth and are brought under the plough gradually disappear—that

for instance, the Wartsberg, near the village of Ackershagen in

Mecklenburg, which I once, as a child, considered to be the highest

mountain in the world, has quite vanished in 40 years—so it is equally

a fact, that hills on which, in the course of thousands of years, new

buildings have been continually erected upon the ruins of former

buildings, gain very considerably in circumference and height. The hill

of Hissarlik furnishes the most striking proof of this. As already

mentioned, it lies at the north-western end of the site of Ilium, which

is distinctly indicated by the surrounding walls built by Lysimachus.

In

addition to the imposing situation of this hill within the circuit of

the town, its present Turkish name of Hissarlik, “fortress” or

“acropolis”—from{61} the word ??????? root ??????, to enclose, which

has passed from the Arabic into the Turkish—seems also to prove that

this is the Pergamus of Ilium; that here Xerxes (in 480 B.C.) offered

up 1000 oxen to the Ilian Athena;[80] that here Alexander the Great

hung up his armour in the temple of the goddess, and took away in its

stead some of the weapons dedicated therein belonging to the time of

the Trojan war, and likewise sacrificed to the Ilian Athena.[81] I

conjectured that this temple, the pride of the Ilians, must have stood

on the highest point of the hill, and I therefore decided to excavate

this locality down to the native soil.

But in order, at the

same time, to bring to light the most ancient of the fortifying walls

of the Pergamus, and to decide accurately how much the hill had

increased in breadth by the débris which had been thrown down since the

erection of those walls, I made an immense cutting on the face of the

steep northern slope, about 66 feet from my last year’s work.[82] This

cutting was made in a direction due south, and extended across the

highest plateau, and was so broad that it embraced the whole building,

the foundations of which, consisting of large hewn stones, I had

already laid open last year to a depth of from only 1 to 3 feet below

the surface. According to an exact measurement, this building, which

appears to belong to the first century after Christ, is about 59 feet

in length, and 43 feet in breadth. I have of course had all these

foundations removed as, being within my excavation, they were of no use

and would only have been in the way.

The difficulty of making

excavations in a wilderness like this, where everything is wanting, are

immense and they increase day by day; for, on account of the steep{62}

slope of the hill, the cutting becomes longer the deeper I dig, and so

the difficulty of removing the rubbish is always increasing. This,

moreover, cannot be thrown directly down the slope, for it would of

course only have to be carried away again; so it has to be thrown down

on the steep side of the hill at some distance to the right and left of

the mouth of the cutting. The numbers of immense blocks of stone also,

which we continually come upon, cause great trouble and have to be got

out and removed, which takes up a great deal of time, for at the moment

when a large block of this kind is rolled to the edge of the slope, all

of my workmen leave their own work and hurry off to see the enormous

weight roll down its steep path with a thundering noise and settle

itself at some distance in the Plain. It is, moreover, an absolute

impossibility for me, who am the only one to preside over all, to give

each workman his right occupation, and to watch that each does his

duty. Then, for the purpose of carrying away the rubbish, the side

passages have to be kept in order, which likewise runs away with a

great deal of time, for their inclinations have to be considerably

modified at each step that we go further down.

Notwithstanding

all these difficulties the work advances rapidly, and if I could only

work on uninterruptedly for a month, I should certainly reach a depth

of more than 32 feet, in spite of the immense breadth of the cutting.

The

medals hitherto discovered are all of copper, and belong for the most

part to Alexandria Troas; some also are of Ilium, and of the first

centuries before and after Christ.

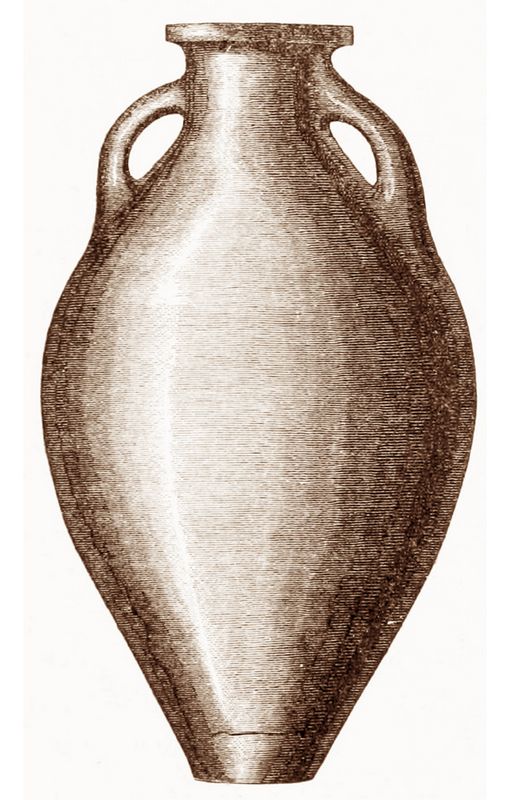

Fig.36: A large Trojan Amphora of Terra-cotta (8m depth).

I

naturally have no leisure here, and I have only been able to write the

above because it is raining heavily, and therefore no work can be done.

On the next rainy day I shall report further on the progress of my

excavations. {64}

Footnotes:

[74]

This date refers to Dr. Schliemann’s former opinion, that there were

Byzantine remains at Hissarlik. He now places the final destruction of

Ilium in the fourth century, on the evidence of the latest coins found

there. See see p. 318, 319.—Ed.

[75] Voyage de la Troade (3e éd. Paris, 1802).

[76] See Plan I., of Greek Ilium, at the end of the volume.

[77] See the Frontispiece.

[78] See Plan II., of the Excavations, at the end of the volume.

[79] The Turkish piaster is somewhat over twopence English.

[80] Herod. VII. 43.

[81] Strabo, XIII. 1. 8; Arrian, I. 11.; Plutarch, Life of Alexander the Great, viii.

[82] See Plan II., of the Excavations.

Continue to Chapter 2.

|

|