|

Introduction.

THE

present book is a sort of Diary of my excavations at Troy, for all the

memoirs of which it consists were, as the vividness of the descriptions

will prove, written down by me on the spot while proceeding with my

works.[32]

Plate 1: View of Hissarlik from the north, after the excavations.

If my memoirs now and then contain contradictions, I

hope that these may be pardoned when it is considered that I have here

revealed a new world for archćology, that the objects which I have

brought to light by thousands are of a kind hitherto never or but very

rarely found, and that consequently everything appeared strange and

mysterious to me. Hence I frequently ventured upon conjectures which I

was obliged to give up on mature consideration, till I at last acquired

a thorough insight, and could draw well-founded conclusions from many

actual proofs.

One of my greatest difficulties has been to make

the enormous accumulation of débris at Troy agree with chronology; and

in this—in spite of long-searching and pondering—I have only partially

succeeded. According to Herodotus (VII. 43): “Xerxes in his march

through the Troad, before invading Greece (B.C. 480) arrived at the

Scamander and went up to Priam’s Pergamus, as he wished to see that

citadel; and, after having seen it, and inquired into its past

fortunes, he sacrificed 1000 oxen to the Ilian Athena, and the Magi

poured libations to the manes of the heroes.”

This passage

tacitly implies that at that time a Greek colony had long since held

possession of the town, and, according to Strabo’s testimony (XIII. i.

42), such a colony{13} built Ilium during the dominion of the Lydians.

Now, as the commencement of the Lydian dominion dates from the year 797

B.C., and as the Ilians seem to have been completely established there

long before the arrival of Xerxes in 480 B.C., we may fairly assume

that their first settlement in Troy took place about 700 B.C. The

house-walls of Hellenic architecture, consisting of large stones

without cement, as well as the remains of Greek household utensils, do

not, however, extend in any case to a depth of more than two meters (6˝

feet) in the excavations on the flat surface of the hill.

As I

find in Ilium no inscriptions later than those belonging to the second

century after Christ, and no coins of a later date than Constans II.

and Constantine II., but very many belonging to these two emperors, as

well as to Constantine the Great, it may be regarded as certain that

the town began to decay even before the time of Constantine the Great,

who, as is well known, at first intended to build Constantinople on

that site; but that it remained an inhabited place till about the end

of the reign of Constans II., that is till about A.D. 361.

But the

accumulation of débris during this long period of 1061 years amounts

only to two meters or 6˝ feet, whereas we have still to dig to a depth

of 12 meters or 40 feet, and in many places even to 14 meters or 46˝

feet, below this, before reaching the native ground which consists of

shelly limestone (Muschelkalk). This immense layer of débris from 40 to

46˝ feet thick, which has been left by the four different nations that

successively inhabited the hill before the arrival of the Greek colony,

that is before 700 B.C., is an immensely rich cornucopia of the most

remarkable terra-cottas, such as have never been seen before, and of

other objects which have not the most distant resemblance to the

productions of Hellenic art.

The question now forces itself upon

us:—Whether this enormous mass of ruins may not have been brought from

another place to increase the height of the hill? Such an hypothesis,

as every{14} visitor to my excavations may convince himself at the

first glance, is perfectly impossible; because in all the strata of

débris, from the native rock, at a depth of from 14 to 16 meters (46 to

52˝ feet) up to 4 meters (13 feet) below the surface, we continually

see remains of masonry, which rest upon strong foundations, and are the

ruins of real houses; and, moreover, because all the numerous large

wine, water, and funereal urns that are met with are found in an

upright position.

The next question is:—But how many centuries have

been required to form a layer of débris, 40 and even 46˝ feet thick,

from the ruins of pre-Hellenic houses, if the formation of the

uppermost one, the Greek layer of 6˝ feet thick, required 1061 years?

During my three years’ excavations in the depths of Troy, I have had

daily and hourly opportunities of convincing myself that, from the

standard of our own or of the ancient Greek mode of life, we can form

no idea of the life and doings of the four nations which successively

inhabited this hill before the time of the Greek settlement. They must

have had a terrible time of it, otherwise we should not find the walls

of one house upon the ruined remains of another, in continuous but

irregular succession; and it is just because we can form no idea of the

way in which these nations lived and what calamities they had to

endure, that it is impossible to calculate the duration of their

existence, even approximately, from the thickness of their ruins. It is

extremely remarkable, but perfectly intelligible from the continual

calamities which befel the town, that the civilization of all the four

nations constantly declined; the terra-cottas, which show continuous

décadence, leave no doubt of this.

{15}The first settlement on

this hill of Hissarlik seems, however, to have been of the longest

duration, for its ruins cover the rock to a height of from 4 to 6

meters (13 to 20 feet). Its houses and walls of fortification were

built of stones, large and small, joined with earth, and manifold

remains of these may be seen in my excavations. I thought last year

that these settlers were identical with the Trojans of whom Homer

sings, because I imagined that I had found among their ruins fragments

of the double cup, the Homeric “d?pa? ?µf???pe????.” From closer

examination, however, it has become evident that these fragments were

the remains of simple cups with a hollow stem, which can never have

been used as a second cup. Moreover, I believe that in my memoirs of

this year (1873) I have sufficiently proved that Aristotle (Hist.

Anim., IX. 40) is wrong in assigning to the Homeric “d?pa?

?µf???pe????” the form of a bee’s cell, whence this cup has ever since

been erroneously interpreted as a double cup, and that it can mean

nothing but a cup with a handle on either side. Cups of such a form are

never met with in the débris of the first settlement of this hill; but

they frequently occur, and in great quantities, among those of thesucceeding people, and also among those of the two later nations which

preceded the Greek colony on the spot. The large golden cup with two

handles, weighing 600 grammes (a pound and a half), which I found in

the royal treasure at the depth of 28 feet in the débris of the second

people, leaves no doubt of this fact.[33]

The

terra-cottas which I found on the native rock, at a depth of 14 meters

(46 feet), are all of a more excellent quality than any met with in the

upper strata. They are of a brilliant black, red, or brown colour,

ornamented with patterns cut and filled with a white substance; the

flat cups have horizontal rings on two sides, the vases have generally

two perpendicular rings on each side for hanging them up with cords. Of

painted terra-cottas I found only one fragment (fig.1).[34]

Fig.1: Fragment of painted pottery from the lowest stratum (16m depth.)

{16}All

that can be said of the first settlers is that they belonged to the

Aryan race, as is sufficiently proved by the Aryan religious symbols

met with in the strata of their ruins (among which we find the Suastika

?), both upon the pieces of pottery and upon the small curious

terra-cottas with a hole in the centre, which have the form of the

crater of a volcano or of a carrousel (i.e. a top).[35]

The

excavations made this year (1873) have sufficiently proved that the

second nation which built a town on this hill, upon the débris of the

first settlers (which is from 13 to 20 feet deep), are the Trojans o

whom Homer sings. Their débris lies from 7 to 10 meters, or 23 to 33

feet, below the surface. This Trojan stratum, which, without exception,

bears marks of great heat, consists mainly of red ashes of wood, which

rise from 5 to 10 feet above the Great Tower of Ilium, the double Scćan

Gate, and the great enclosing Wall, the construction of which Homer

ascribes to Poseidon and Apollo; and they show that the town was

destroyed by a fearful conflagration. How great the heat must have been

is clear also from the large slabs of stone upon the road leading from

the double Scćan Gate down to the Plain: for when I laid this road open

a few months ago, all the slabs appeared as uninjured as if they had

been put down quite recently; but after they had been exposed to the

air for a few days, the slabs of the upper part of the road, to the

extent of some{17} 10 feet, which had been exposed to the heat, began

to crumble away, and they have now almost disappeared, while those of

the lower portion of the road, which had not been touched by the fire,

have remained uninjured, and seem to be indestructible.

A further proof

of the terrible catastrophe is furnished by a stratum of scorić of

melted lead and copper, from 1/5 to 1-1/5 of an inch thick, which

extends nearly through the whole hill at a depth of from 28 to 29˝

feet. That Troy was destroyed by enemies after a bloody war is further

attested by the many human bones which I found in these heaps of

débris, and above all by the skeletons with helmets, found in the

depths of the temple of Athena;[36] for, as we know from Homer, all

corpses were burnt and the ashes were preserved in urns. Of such urns I

have found an immense number in all the pre-Hellenic strata on the

hill. Lastly, the Treasure, which some member of the royal family had

probably endeavoured to save during the destruction of the city, but

was forced to abandon, leaves no doubt that the city was destroyed by

the hands of enemies. I found this Treasure on the large enclosing wall

by the side of the royal palace, at a depth of 27˝ feet, and covered

with red Trojan ashes from 5 to 6˝ feet in depth, above which was a

post-Trojan wall of fortification 19˝ feet high.

Trusting to the

data of the Iliad, the exactness of which I used to believe in as in

the Gospel itself, I imagined that Hissarlik, the hill which I have

ransacked for three years, was the Pergamus of the city, that Troy must

have had 50,000 inhabitants, and that its area must have extended over

the whole space occupied by the Greek colony of Ilium.[37]

Notwithstanding

this, I was determined to investigate the matter accurately, and I

thought that I could not do so in any better way than by making

borings. I accordingly began cautiously to dig at the extreme ends of

the{18} Greek Ilium; but these borings down to the native rock brought

to light only walls of houses, and fragments of pottery belonging to

the Greek period,—not a trace of the remains of the preceding

occupants. In making these borings, therefore, I gradually came nearer

to the fancied Pergamus, but without any better success; till at last

as many as seven shafts, which I dug at the very foot of the hill down

to the rock, produced only Greek masonry and fragments of Greek

pottery. I now therefore assert most positively that Troy was limited

to the small surface of this hill; that its area is accurately marked

by its great surrounding wall, laid open by me in many places; that the

city had no Acropolis, and that the Pergamus is a pure invention of

Homer; and further that the area of Troy in post-Trojan times down to

the Greek settlement was only increased so far as the hill was enlarged

by the débris that was thrown down, but that the Ilium of the Greek

colony had a much larger extent at the time of its foundation.[38]

Though,

however, we find on the one hand that we have been deceived in regard

to the size of Troy, yet on the other we must feel great satisfaction

in the certainty, now at length ascertained, that Troy really existed,

that the greater portion of this Troy has been brought to light by me,

and that the Iliad—although on an exaggerated scale—sings of this city

and of the fact of its tragic end. Homer, however, is no historian, but

an epic poet, and hence we must excuse his exaggerations.

As

Homer is so well informed about the topography and the climatic

conditions of the Troad, there can surely be no doubt that he had

himself visited Troy. But, as he was there long after its destruction,

and its site had moreover been buried deep in the débris of the ruined

town, and had for centuries been built over by a new town, Homer

could{19} neither have seen the Great Tower of Ilium nor the Scćan

Gate, nor the great enclosing Wall, nor the palace of Priam; for, as

every visitor to the Troad may convince himself by my excavations, the

ruins and red ashes of Troy alone—forming a layer of from five to ten

feet thick—covered all these remains of immortal fame; and this

accumulation of débris must have been much more considerable at the

time of Homer’s visit.

Homer made no excavations so as to bring those

remains to light, but he knew of them from tradition; for the tragic

fate of Troy had for centuries been in the mouths of all minstrels, and

the interest attached to it was so great that, as my excavations have

proved, tradition itself gave the exact truth in many details. Such,

for instance, is the memory of the Scćan Gate in the Great Tower of

Ilium, and the constant use of the name Scćan Gate in the plural,

because it had to be described as double,[39] and in fact it has been

proved to be a double gate. According to the lines in the Iliad (XX.

307, 308), it now seems to me extremely probable that, at the time of

Homer’s visit, the King of Troy declared that his race was descended in

a direct line from Ćneas.[40]

Now as Homer never saw Ilium’s

Great Tower, nor the Scćan Gate, and could not imagine that these

buildings lay buried deep beneath his feet, and as he probably imagined

Troy to have been very large—according to the then existing poetical

legends—and perhaps wished to{20} describe it as still larger, we

cannot be surprised that he makes Hector descend from the palace in the

Pergamus and hurry through the town in order to arrive at the Scćan

Gate; whereas that gate and Ilium’s Great Tower, in which it stands,

are in reality directly in front of the royal house. That this house is

really the king’s palace seems evident from its size, from the

thickness of its stone walls, in contrast to those of the other houses

of the town, which are built almost exclusively of unburnt bricks, and

from its imposing situation upon an artificial hill directly in front

of or beside the Scćan Gate, the Great Tower, and the great surrounding

Wall.

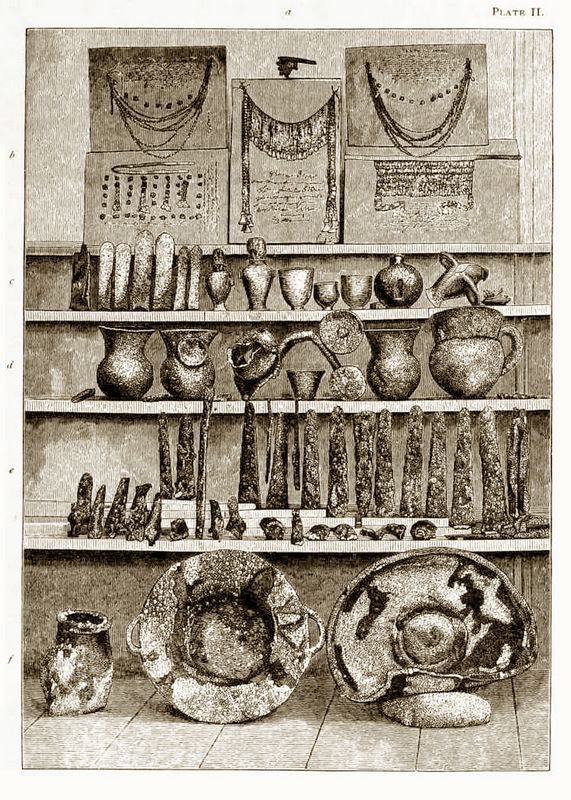

This is confirmed by the many splendid objects found in its

ruins, especially the enormous royally ornamented vase with the picture

of the owl-headed goddess Athena, the tutelary divinity of Ilium (see

No. 219, p. 307); and lastly, above all other things, by the rich

Treasure found close by it (Plate II.). I cannot, of course, prove that

the name of this king, the owner of this treasure, was really PRIAM;

but I give him this name because he is so called by Homer and in all

the traditions. All that I can prove is, that the palace of the owner

of this treasure, this last Trojan king, perished in the great

catastrophe, which destroyed the Scćan Gate, the great surrounding

Wall, and the Great Tower, and which desolated the whole city.

I can

prove, by the enormous quantities of red and yellow calcined Trojan

ruins, from five to ten feet in height, which covered and enveloped

these edifices, and by the many post-Trojan buildings, which were again

erected upon these calcined heaps of ruins, that neither the palace of

the owner of the Treasure, nor the Scćan Gate, nor the great

surrounding Wall, nor Ilium’s Great Tower, were ever again brought to

light. A city, whose king possessed such a treasure, was immensely

wealthy, considering the circumstances of those times; and because Troy

was rich, it was powerful, had many subjects, and obtained auxiliaries

from all quarters.

Troy had therefore no separate Acropolis; but

as one was necessary for the great deeds of the Iliad, it was added by

the poetical invention of Homer, and called by him Pergamus, a word of

quite unknown derivation.

Last year I ascribed the building of

the Great Tower of{21} Ilium to the first occupants of the hill; but I

have long since come to the firm conviction that it is the work of the

second people, the Trojans, because it is upon the north side only,

within the Trojan stratum of ruins, and from 16 to 19˝ feet above the

native soil, that it is made of actual masonry. I have, in my letters,

repeatedly drawn attention to the fact, that the terra-cottas which I

found upon the Tower can only be compared with those found at a depth

of from 36 to 46 feet. This, however, applies only to the beauty of the

clay and the elegance of the vessels, but in no way to their types,

which, as the reader may convince himself from the illustrations to

this work, are utterly different from the pottery of the first settlers.

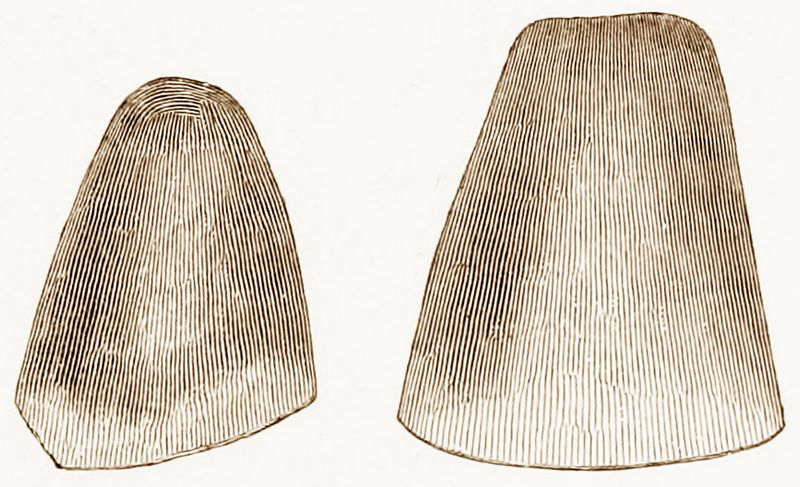

Fig.2: Small Trojan Axes of Diorite (8m depth).

Those, however, in

the Trojan stratum, from 23 to 33 feet below the surface, are in

general of much better workmanship than those above. I wish to draw

attention to the fact that unfortunately, when writing the present

book, I made the mistake, which is now inconceivable to me, of applying

the name of wedges to those splendidly-cut weapons and implements, the

greater part of which are made of diorite, but frequently also of very

hard and transparent green stone, such as are given here and in several

later illustrations. They are, however, as anyone can convince himself,

not wedges but{22} axes, and the majority of them must have been used

as battle-axes. Many, to judge from their form, seem to be excellently

fitted to be employed as lances, and may have been used as such.

I have

collected many hundreds of them. But, together with the thousands of

stone implements, I found also many of copper; and the frequently

discovered moulds of mica-schist for casting copper weapons and

implements, as well as the many small crucibles, and small roughly made

bowls, spoons, and funnels for filling the moulds, prove that this

metal was much used. The strata of copper and lead scorić, met with at

a depth of from 28 to 29˝ feet, leave no doubt that this was the case.

It must be observed that all the copper articles met with are of pure

copper, without the admixture of any other metal.[41] Even the king’s

Treasure contained, besides other articles made of this metal, a shield

with a large boss in the centre; a great caldron; a kettle or vase; a

long slab with a silver vase welded on to it by the conflagration; and

many fragments of other vases.[42]

Plate II: General view of the Treasure of Priam (Depth 8˝ m.)

This treasure

further leaves no doubt that Homer must have actually seen gold and

silver articles, such as he continually describes; it is, in every

respect, of{23} inestimable value to science, and will for centuries

remain the object of careful investigation.

Unfortunately upon

none of the articles of the Treasure do I find an inscription, or any

other religious symbols, except the 100 idols of the Homeric “?e?

??a???p?? ?????,” which glitter upon the two diadems and the four

ear-rings. These are, however, an irrefragable proof that the Treasure

belongs to the city and to the age of which Homer sings.

Fig.3: Inscribed Terra-cotta Vase from the Palace (8m depth.). Below: The Inscription thereon.

Yet a written language was not wanting at that time. For instance, I found

at a depth of 26 feet, in the royal palace, the vase with an

inscription, of which a drawing is here given (fig.3); and I wish to call

especial attention to the fact, that of the characters occurring in it,

the letter like the Greek P occurs also in the inscription on a seal,

found at the depth of 23 feet (fig.4); the second and third letter to the left

of this upon a whorl of terra-cotta,[43]{24} likewise found at a depth

of 23 feet; and the third letter also upon two small funnels of

terra-cotta, from a depth of 10 feet (see p. 191).

I further found in

the royal palace the excellent engraved inscription on a piece of red

slate (fig.5); but I see here only one character resembling one of the letters

of the inscription on the above-mentioned seal. My friend the great

Indian scholar, Émile Burnouf, conjectures that all these characters

belong to a very ancient Grćco-Asiatic local alphabet.

Fig.4: Inscribed Terra-cotta Seal (7m depth.).

Professor H.

Brunn, of Munich, writes to me that he has shown these inscriptions to

Professor Haug, and that he has pointed out their relationship and

connection with the Phœnician alphabet (from which the Greek alphabet

is however derived), and has found certain analogies between them and

the inscription on the bronze table which was found at Idalium in

Cyprus, and is now in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris. Professor

Brunn adds that the connection of things found at Troy with those found

in Cyprus is in no way surprising, but may be very well reconciled with

Homer, and that at all events particular attention should be paid to

this connection, for, in his opinion, Cyprus is the{25} cradle of Greek

art, or, so to speak, the caldron in which Asiatic, Egyptian, and Greek

ingredients were brewed together, and out of which, at a later period,

Greek art came forth as the clear product.

Fig.5: Piece of Red Slate, perhaps a Whetstone, with an Inscription (7m depth).

Footnotes:

[32] Each of these Memoirs forms a chapter of the Translation.

[33] For this remarkable vessel see Chapter XXIII. and Plate XVII.

[34] But a second was found in the stratum above (see the Illustration, No. 35, at the end of the Introduction).

[35] The word by which Dr. Schliemann usually denotes these curious objects is carrousels, as a translation of fusaioli,

the term applied by the Italian antiquaries to the similar objects

found in the marshes about Modena. It is difficult to choose an English

word, without assuming their use on the one hand, or not being specific

enough on the other. Top and teetotum are objectionable on the former

grounds, and wheel is objectionable on both. On the whole, whorl seems

most convenient, and Dr. Schliemann gives his approval to this term.

Their various shapes are shown in the Plates at the end of the volume.

Those in the form of single cones, with flat bases, seem to be what Dr.

Schliemann calls volcanoes (Vulkans), the hole representing the

crater.—[Ed.]

[36] See p. 280.

[37] See the Plan of Greek Ilium (Plan I.).

[38] See the Plan of Dr. Schliemann’s Researches. (Plan II.).

[39]

The double form of an outer and inner gate, and the use of πύλαι in the

plural for a city gate, are both far too frequent to justify our

founding an argument merely on the plural form of the Σκαίαι

πύλαι.—[Ed.]

[40]

Νῦν δὲ δὴ Αἰνείαο βίη Τρώεσσιν ἀνάξει,

Καὶ παίδων παῖδες, τοί κεν μετόπισθε γένωνται.

“But o’er the Trojans shall Ćneas reign,

And his sons’ sons, through ages yet unborn.”

This

is the declaration of Poseidon to the gods, when Ćneas was in peril of

his life by the sword of Achilles. (But compare p. 182).—[Ed.]

[41] To this statement there are at least some exceptions. See the Analysis by M. Damour, of Lyon, at the end of the book.—[Ed.]

[42]

We omit here the Author’s further enumeration of the objects composing

the “King’s Treasure,” as they are fully described on the occasion of

their wonderful discovery (Chapter XXIII.). Meanwhile the Plate

opposite gives a general view of the whole.—[Ed.]

[43] Engraved

among the lithographic plates at the end of the volume, Pl. LI., No.

496. Since the publication of Dr. Schliemann’s work, many of these

Trojan inscriptions have been more certainly determined to be real

inscriptions have been more certainly determined to be real

inscriptions in the Cyprian syllabic character, through the researches

of Dr. Martin Haug and Professor Gomperz of Vienna. (See the

Appendix.)—[Ed.]

[Continue to part B of Introduction]

|

|