| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Travels in Tartary, Thibet, and China

During the years 1844-5-6. Volume 1Evariste Regis Huc

| | | | |

|

Chapter 1

French

Mission of Peking—Glance at the Kingdom of Ouniot — Preparations for

Departure — Tartar-Chinese Inn—Change of Costume—Portrait and Character

of Samdadchiemba—Sain-Oula (the Good Mountain)—The Frosts on Sain-Oula,

and its Robbers—First Encampment in the Desert—Great Imperial

Forest—Buddhist monuments on the summit of the mountains —Topography of

the Kingdom of Gechekten—Character of its Inhabitants—Tragical working

of a Mine—Two Mongols desire to have their horoscope taken —Adventure of

Samdadchiemba —Environs of the town of Tolon-Noor.

Fig.1: xxxx

The French mission of Peking, once so flourishing under the

early emperors of the Tartar-Mantchou dynasty, was almost extirpated by

the constant persecutions of Kia-King, the fifth monarch of that

dynasty, who ascended the throne in 1799. The missionaries were

dispersed or put to death, and at that time Europe was herself too

deeply agitated to enable her to send succour to this distant

Christendom, which remained for a time abandoned. Accordingly,

when the French Lazarists re-appeared at Peking, they found there

scarce a vestige of the true faith. A great number of Christians,

to avoid (p.10) the persecutions of the Chinese authorities, had passed

the Great Wall, and sought peace and liberty in the deserts of Tartary,

where they lived dispersed upon small patches of land which the Mongols

permitted them to cultivate. By dint of perseverance the

missionaries collected together these dispersed Christians, placed

themselves at their head, and hence superintended the mission of

Peking, the immediate administration of which was in the hands of a few

Chinese Lazarists. The French missionaries could not, with any

prudence, have resumed their former position in the capital of the

empire. Their presence would have compromised the prospects of

the scarcely reviving mission.

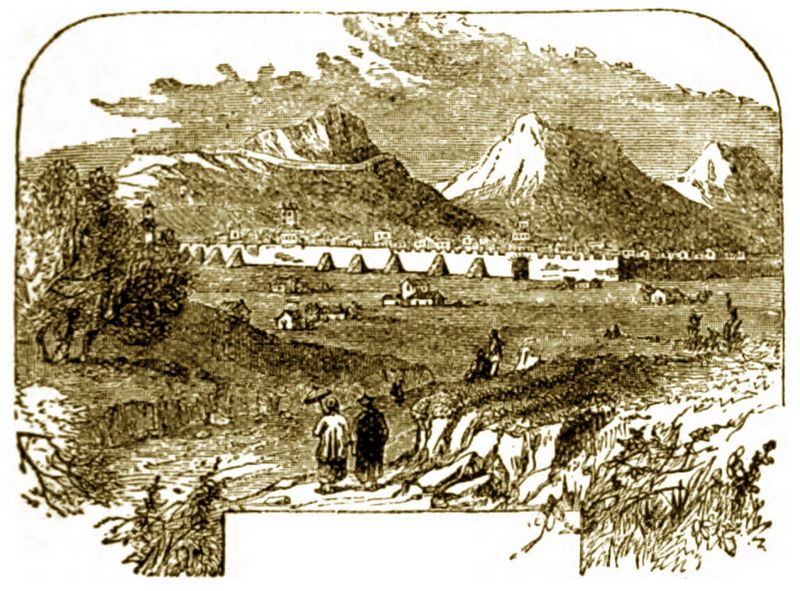

Fig.2: View of Peking.

In visiting the Chinese

Christians of Mongolia, we more than once had occasion to make

excursions into the Land of Grass, (Isao-Ti), as the uncultivated

portions of Tartary are designated, and to take up our temporary abode

beneath the tents of the Mongols. We were no sooner acquainted

with this nomadic people, than we loved them, and our hearts were

filled with a passionate desire to announce the gospel to them.

Our whole leisure was therefore devoted to acquiring the Tartar

dialects, and in 1842, the Holy See at length fulfilled our desires, by

erecting Mongolia into an Apostolical Vicariat.

Towards the

commencement of the year 1844, couriers arrived at Si-wang, a small

Christian community, where the vicar apostolic of Mongolia had fixed

his episcopal residence. Si-wang itself is a village, north of

the Great Wall, one day’s journey from Suen-hoa-Fou. The prelate

sent us instructions for an extended voyage we were to undertake for

the purpose of studying the character and manners of the Tartars, and

of ascertaining as nearly as possible the extent and limits of the

Vicariat. This journey, then, which we had so long meditated, was

now determined upon; and we sent a young Lama convert in search of some

camels which we had put to pasture in the kingdom of Naiman.

Pending his absence, we hastened the completion of several Mongol

works, the translation of which had occupied us for a considerable

time. Our little books of prayer and doctrine were ready, still

our young Lama had not returned; but thinking he could not delay much

longer, we quitted the valley of Black Waters (Hé-Chuy), and proceeded

on to await his arrival at the Contiguous Defiles (Pié-lié-Keou) which

seemed more favourable for the completion of our preparations.

The days passed away in futile expectation; the coolness of the autumn

was becoming somewhat biting, and we feared that we should have to

begin our journey across the deserts of Tartary during the frosts of

winter. We determined, therefore, to dispatch some one in quest

of our camels and our Lama. A friendly (p.11) catechist, a good

walker and a man of expedition, proceeded on this mission. On the

day fixed for that purpose he returned; his researches had been wholly

without result. All he had ascertained at the place which he had

visited was, that our Lama had started several days before with our

camels. The surprise of our courier was extreme when he found

that the Lama had not reached us before himself. “What!”

exclaimed he, “are my legs quicker than a camel’s! They left

Naiman before me, and here I am arrived before them! My spiritual

fathers, have patience for another day. I’ll answer that both

Lama and camels will be here in that time.” Several days,

however, passed away, and we were still in the same position. We

once more dispatched the courier in search of the Lama, enjoining him

to proceed to the very place where the camels had been put to pasture,

to examine things with his own eyes, and not to trust to any statement

that other people might make.

During this interval of painful

suspense, we continued to inhabit the Contiguous Defiles, a Tartar

district dependent on the kingdom of Ouniot. [11] These regions

appear to have been affected by great revolutions. The present

inhabitants state that, in the olden time, the country was occupied by

Corean tribes, who, expelled thence in the course of various wars, took

refuge in the peninsula which they still possess, between the Yellow

Sea and the sea of Japan. You often, in these parts of Tartary,

meet with the remains of great towns, and the ruins of fortresses, very

nearly resembling those of the middle ages in Europe, and, upon turning

up the soil in these places, it is not unusual to find lances, arrows,

portions of farming implements, and urns filled with Corean money.

Towards

the middle of the 17th century, the Chinese began to penetrate into

this district. At that period, the whole landscape was still one

of rude grandeur; the mountains were covered with fine forests, and the

Mongol tents whitened the valleys, amid rich pasturages. For a

very moderate sum the Chinese obtained permission to cultivate the

desert, and as cultivation advanced, the Mongols were obliged to

retreat, conducting their flocks and herds elsewhere.

From that

time forth, the aspect of the country became entirely changed.

All the trees were grubbed up, the forests disappeared from the hills,

the prairies were cleared by means of fire, and the new cultivators set

busily to work in exhausting the fecundity of the soil. Almost

the entire region is now in the hands of the Chinese, and it is

probably to their system of devastation that we must (p.12) attribute the

extreme irregularity of the seasons which now desolate this unhappy

land. Droughts are of almost annual occurrence; the spring winds

setting in, dry up the soil; the heavens assume a sinister aspect, and

the unfortunate population await, in utter terror, the manifestation of

some terrible calamity; the winds by degrees redouble their violence,

and sometimes continue to blow far into the summer months. Then

the dust rises in clouds, the atmosphere becomes thick and dark; and

often, at mid-day, you are environed with the terrors of night, or

rather, with an intense and almost palpable blackness, a thousand times

more fearful than the most sombre night. Next after these

hurricanes comes the rain: but so comes, that instead of being an

object of desire, it is an object of dread, for it pours down in

furious raging torrents. Sometimes the heavens suddenly opening,

pour forth in, as it were, an immense cascade, all the water with which

they are charged in that quarter; and immediately the fields and their

crops disappear under a sea of mud, whose enormous waves follow the

course of the valleys, and carry everything before them. The

torrent rushes on, and in a few hours the earth reappears; but the

crops are gone, and worse even than that, the arable soil also has gone

with them. Nothing remains but a ramification of deep ruts,

filled with gravel, and thenceforth incapable of being ploughed.

Hail

is of frequent occurrence in these unhappy districts, and the

dimensions of the hailstones are generally enormous. We have

ourselves seen some that weighed twelve pounds. One moment

sometimes suffices to exterminate whole flocks. In 1843, during

one of these storms, there was heard in the air a sound as of a rushing

wind, and therewith fell, in a field near a house, a mass of ice larger

than an ordinary millstone. It was broken to pieces with

hatchets, yet, though the sun burned fiercely, three days elapsed

before these pieces entirely melted.

The droughts and the

inundations together, sometimes occasion famines which well nigh

exterminate the inhabitants. That of 1832, in the twelfth year of

the reign of Tao-Kouang, [12] is the most terrible of these on

record. The Chinese report that it was everywhere announced by a

general presentiment, the exact nature of which no one could explain or

comprehend. During the winter of 1831, a dark rumour grew into

circulation. Next year, it was said, there will be neither rich

nor poor; blood will cover the mountains; bones will fill the valleys

(Ou fou, ou kioung; hue man chan, kou man tchouan.) These words

were in every one’s mouth; the children repeated them in their sports;

all were under the p. 13domination of these sinister apprehensions when

the year 1832 commenced. Spring and summer passed away without

rain, and the frosts of autumn set in while the crops were yet green;

these crops of course perished, and there was absolutely no

harvest. The population was soon reduced to the most entire

destitution. Houses, fields, cattle, everything was exchanged for

grain, the price of which attained its weight in gold. When the

grass on the mountain sides was devoured by the starving creatures, the

depths of the earth were dug into for roots. The fearful

prognostic, that had been so often repeated, became accomplished.

Thousands died upon the hills, whither they had crawled in search of

grass; dead bodies filled the roads and houses; whole villages were

depopulated to the last man. There was, indeed, neither rich nor

poor; pitiless famine had levelled all alike.

It was in this

dismal region that we awaited with impatience the courier, whom, for a

second time, we had dispatched into the kingdom of Naiman. The

day fixed for his return came and passed, and several others followed,

but brought no camels, nor Lama, nor courier, which seemed to us most

astonishing of all. We became desperate; we could not longer

endure this painful and futile suspense. We devised other means

of proceeding, since those we had arranged appeared to be

frustrated. The day of our departure was fixed; it was settled,

further, that one of our Christians should convey us in his car to

Tolon-Noor, distant from the Contiguous Defiles about fifty

leagues. At Tolon-Noor we were to dismiss our temporary

conveyance, proceed alone into the desert, and thus start on our

pilgrimage as well as we could. This project absolutely stupified

our Christian friends; they could not comprehend how two Europeans

should undertake by themselves a long journey through an unknown and

inimical country: but we had reasons for abiding by our

resolution. We did not desire that any Chinese should accompany

us. It appeared to us absolutely necessary to throw aside the

fetters with which the authorities had hitherto contrived to shackle

missionaries in China. The excessive caution, or rather the

imbecile pusillanimity of a Chinese catechist, was calculated rather to

impede than to facilitate our progress in Tartary.

On

the

Sunday, the day preceding our arranged departure, every thing was

ready; our small trunks were packed and padlocked, and the Christians

had assembled to bid us adieu. On this very evening, to the

infinite surprise of all of us, our courier arrived. As he

advanced his mournful countenance told us before he spoke, that his

intelligence was unfavourable. “My spiritual fathers,” said he,

“all is lost; you have nothing to hope; in the kingdom of Naiman there

no longer exists any camels of the Holy Church. The Lama (p.14)

doubtless has been killed; and I have no doubt the devil has had a

direct hand in the matter.”

Doubts and fears are often harder to

bear than the certainty of evil. The intelligence thus received,

though lamentable in itself, relieved us from our perplexity as to the

past, without in any way altering our plan for the future. After

having received the condolences of our Christians, we retired to rest,

convinced that this night would certainly be that preceding our nomadic

life.

The night was far advanced, when suddenly numerous voices

were heard outside our abode, and the door was shaken with loud and

repeated knocks. We rose at once; the Lama, the camels, all had

arrived; there was quite a little revolution. The order of the

day was instantly changed. We resolved to depart, not on the

Monday, but on the Tuesday; not in a car, but on camels, in true Tartar

fashion. We returned to our beds perfectly delighted; but we

could not sleep, each of us occupying the remainder of the night with

plans for effecting the equipment of the caravan in the most

expeditious manner possible.

Next day, while we were making our

preparations for departure, our Lama explained his extraordinary

delay. First, he had undergone a long illness; then he had been

occupied a considerable time in pursuing a camel which had escaped into

the desert; and finally, he had to go before some tribunal, in order to

procure the restitution of a mule which had been stolen from him.

A law-suit, an illness, and a camel hunt were amply sufficient reasons

for excusing the delay which had occurred. Our courier was the

only person who did not participate in the general joy; he saw it must

be evident to every one that he had not fulfilled his mission with any

sort of skill.

All Monday was occupied in the equipment of our

caravan. Every person gave his assistance to this object.

Some repaired our travelling-house, that is to say, mended or patched a

great blue linen tent; others cut for us a supply of wooden tent pins;

others mended the holes in our copper kettle, and renovated the broken

leg of a joint stool; others prepared cords, and put together the

thousand and one pieces of a camel’s pack. Tailors, carpenters,

braziers, rope-makers, saddle-makers, people of all trades assembled in

active co-operation in the court-yard of our humble abode. For

all, great and small, among our Christians, were resolved that their

spiritual fathers should proceed on their journey as comfortably as

possible.

On Tuesday morning, there remained nothing to be done

but to perforate the nostrils of the camels, and to insert in the

aperture a wooden peg, to use as a sort of bit. The arrangement

of this was [p 15] left to our Lama. The wild piercing cries of the

poor animals pending the painful operation, soon collected together all

the Christians of the village. At this moment, our Lama became

exclusively the hero of the expedition. The crowd ranged

themselves in a circle around him; every one was curious to see how, by

gently pulling the cord attached to the peg in its nose, our Lama could

make the animal obey him, and kneel at his pleasure. Then, again,

it was an interesting thing for the Chinese to watch our Lama packing

on the camels’ backs the baggage of the two missionary

travellers. When the arrangements were completed, we drank a cup

of tea, and proceeded to the chapel; the Christians recited prayers for

our safe journey; we received their farewell, interrupted with tears,

and proceeded on our way. Samdadchiemba, our Lama cameleer,

gravely mounted on a black, stunted, meagre mule, opened the march,

leading two camels laden with our baggage; then came the two

missionaries, MM. Gabet and Huc, the former mounted on a tall camel,

the latter on a white horse.

Upon our departure we were resolved to lay aside our accustomed

usages, and to become regular Tartars. Yet we did not at the

outset, and all at once, become exempt from the Chinese system.

Besides that, for the first mile or two of our journey, we were

escorted by our Chinese Christians, some on foot, and some on

horseback; our first stage was to be an inn kept by the Grand Catechist

of the Contiguous Defiles.

(p.16) The progress of our little

caravan was not at first wholly successful. We were quite novices

in the art of saddling and girdling camels, so that every five minutes

we had to halt, either to rearrange some cord or piece of wood that

hurt and irritated the camels, or to consolidate upon their backs, as

well as we could, the ill-packed baggage that threatened, ever and

anon, to fall to the ground. We advanced, indeed, despite all

these delays, but still very slowly. After journeying about

thirty-five lis, [16] we quitted the cultivated district and entered

upon the Land of Grass. There we got on much better; the camels

were more at their ease in the desert, and their pace became more rapid.

We

ascended a high mountain, where the camels evinced a decided tendency

to compensate themselves for their trouble, by browzing, on either

side, upon the tender stems of the elder tree or the green leaves of

the wild rose. The shouts we were obliged to keep up, in order to

urge forward the indolent beasts, alarmed infinite foxes, who issued

from their holes and rushed off in all directions. On attaining

the summit of the rugged hill we saw in the hollow beneath the

Christian inn of Yan-Pa-Eul. We proceeded towards it, our road

constantly crossed by fresh and limpid streams, which, issuing from the

sides of the mountain, reunite at its foot and form a rivulet which

encircles the inn. We were received by the landlord, or, as the

Chinese call him, the Comptroller of the Chest.

Fig.4: Kang of a Tartar-Chinese Inn (p.17)

Inns of this

description occur at intervals in the deserts of Tartary, along the

confines of China. They consist almost universally of a large

square enclosure, formed by high poles interlaced with brushwood.

In the centre of this enclosure is a mud house, never more than ten

feet high. With the exception of a few wretched rooms at each

extremity, the entire structure consists of one large apartment,

serving at once for cooking, eating, and sleeping; thoroughly dirty,

and full of smoke and intolerable stench. Into this pleasant

place all travellers, without distinction, are ushered, the portion of

space applied to their accommodation being a long, wide Kang, as it is

called, a sort of furnace, occupying more than three-fourths of the

apartment, about four feet high, and the flat, smooth surface of which

is covered with a reed mat, which the richer guests cover again with a

travelling carpet of felt, or with furs. In front of it, three

immense coppers, set in glazed earth, serve for the preparation of the

traveller’s milk-broth. The apertures by which these monster

boilers are heated communicate with the interior of the Kang, so that

its temperature is constantly maintained at a high elevation, even in

the terrible cold of winter.

Upon

the arrival of guests, the Comptroller of the Chest invites them to

ascend the Kang, where they seat themselves, their legs crossed

tailor-fashion, round a large table, not more than six inches

high. The lower part of the room is reserved for the people of

the inn, who there busy themselves in keeping up the fire under the

cauldrons, boiling tea, and pounding oats and buckwheat into flour for

the repast of the travellers. The Kang of these Tartar-Chinese

inns is, till evening, a stage full of animation, where the guests eat,

drink, smoke, gamble, dispute, and fight: with night-fall, the

refectory, tavern, and gambling-house of the day is suddenly converted

into a dormitory. The travellers who have any bed-clothes unroll

and arrange them; those who have none, settle themselves as best they

may in their personal attire, and lie down, side by side, round the

table. When the guests are very numerous they arrange themselves

in two circles, feet to feet. Thus reclined, those so disposed,

sleep; others, awaiting sleep, smoke, drink tea, and gossip. The

effect of the scene, dimly exhibited by an imperfect wick floating amid

thick, dirty, stinking oil, whose receptacle is ordinarily a broken

tea-cup, is fantastic, and to the stranger, fearful.

(p.18) The

Comptroller of the Chest had prepared his own room for our

accommodation. We washed, but would not sleep there; being now

Tartar travellers, and in possession of a good tent, we determined to

try our apprentice hand at setting it up. This resolution

offended no one, it was quite understood we adopted this course, not

out of contempt towards the inn, but out of love for a patriarchal

life. When we had set up our tent, and unrolled on the ground our

goat-skin beds, we lighted a pile of brushwood, for the nights were

already growing cold. Just as we were closing our eyes, the

Inspector of Darkness startled us with beating the official night

alarum, upon his brazen tam-tam, the sonorous sound of which,

reverberating through the adjacent valleys struck with terror the

tigers and wolves frequenting them, and drove them off.

We were

on foot before daylight. Previous to our departure we had to

perform an operation of considerable importance—no other than an entire

change of costume, a complete metamorphosis. The missionaries who

reside in China, all, without exception, wear the secular dress of the

people, and are in no way distinguishable from them; they bear no

outward sign of their religious character. It is a great pity

that they should be thus obliged to wear the secular costume, for it is

an obstacle in the way of their preaching the gospel. Among the

Tartars, a black man—so they discriminate the laity, as wearing their

hair, from the clergy, who have their heads close shaved—who should

talk about religion would be laughed at, as impertinently meddling with

things, the special province of the Lamas, and in no way concerning

him. The reasons which appear to have introduced and maintained

the custom of wearing the secular habit on the part of the missionaries

in China, no longer applying to us, we resolved at length to appear in

an ecclesiastical exterior becoming our sacred mission. The views

of our vicar apostolic on the subject, as explained in his written

instructions, being conformable with our wish, we did not

hesitate. We resolved to adopt the secular dress of the Thibetian

Lamas; that is to say, the dress which they wear when not actually

performing their idolatrous ministry in the Pagodas. The costume

of the Thibetian Lamas suggested itself to our preference as being in

unison with that worn by our young neophyte, Samdadchiemba.

Fig.5: Missionaries in Lamanesque Costume

Breakfast followed this

decisive operation, but it was silent and sad. When the

Comptroller of the Chest brought in some glasses and an urn, wherein

smoked the hot wine drunk by the Chinese, we told him that having

changed our habit of dress, we should change also our habit of

living. “Take away,” said we, “that wine and that chafing dish;

henceforth we renounce drinking and smoking. You know,” added we,

laughing, “that good Lamas abstain from wine and tobacco.” The

Chinese Christians who surrounded us did not join in the laugh; they

looked at us without speaking and with deep commiseration, fully

persuaded that we should inevitably perish of privation and misery in

the deserts of Tartary. Breakfast finished, while the people of

the inn were packing up our tent, saddling the camels, and preparing

for our departure, we took a couple of rolls, baked in the steam of the

furnace, and walked out to complete our meal with some wild currants

growing on the bank of the adjacent rivulet. It was soon

announced to us that everything was ready—so, mounting our respective

animals, we proceeded on the road to Tolon-Noor, accompanied by

Samdadchiemba.

Fig.6: Samdadchiemba

As we have just observed, Samdadchiemba was our only travelling

companion. This young man was neither Chinese, nor Tartar, nor

Thibetian. Yet, at the first glance, it was easy to recognise in

him the features characterizing that which naturalists call the Mongol

race. A great flat nose, insolently turned up; a large mouth,

slit in a perfectly straight line, thick, projecting lips, a deep

bronze complexion, every feature contributed to give to his physiognomy

a wild and scornful aspect.

When his little eyes seemed starting

out of his head from under their lids, wholly destitute of eyelash, and

he looked at you wrinkling his brow, he inspired you at once with

feelings of dread and yet of confidence. The face was without any

decisive character: it exhibited neither the mischievous knavery of the

Chinese, nor the frank good-nature of the Tartar, nor the courageous

energy of the Thibetian; but was made up of a mixture of all

three. Samdadchiemba was a Dchiahour. We shall hereafter

have occasion to speak more in detail of the native country of our

young cameleer.

At the age of eleven, Samdadchiemba had escaped

from his Lamasery, in order to avoid the too frequent and too severe

corrections of the master under whom he was more immediately

placed. He afterwards passed the greater portion of his vagabond

youth, sometimes in the Chinese towns, sometimes in the deserts of

Tartary. It is easy to comprehend that this independent course of

life had not tended to modify the natural asperity of his character;

his intellect was entirely uncultivated; but, on the other hand, his

muscular power was enormous, and he was not a little vain of this

quality, which he took great pleasure in parading. After having

p. 21been instructed and baptized by M. Gabet, he had attached himself

to the service of the missionaries. The journey we were now

undertaking was perfectly in harmony with his erratic and adventurous

taste. He was, however, of no mortal service to us as a guide

across the deserts of Tartary, for he knew no more of the country than

we knew ourselves. Our only informants were a compass, and the

excellent map of the Chinese empire by Andriveau-Goujon.

The

first portion of our journey, after leaving Yan-Pa-Eul, was

accomplished without interruption, sundry anathemas excepted, which

were hurled against us as we ascended a mountain, by a party of Chinese

merchants, whose mules, upon sight of our camels and our own yellow

attire, became frightened, and took to their heels at full speed,

dragging after them, and in one or two instances, overturning the

waggons to which they were harnessed.

Footnotes:

[Continue to Chapter 1, part 2]

|

|

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|