| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Travels in Tartary, Thibet, and China

During the years 1844-5-6. Volume 1Evariste Regis Huc

| | | | |

|

Chapter 1 (part 2)

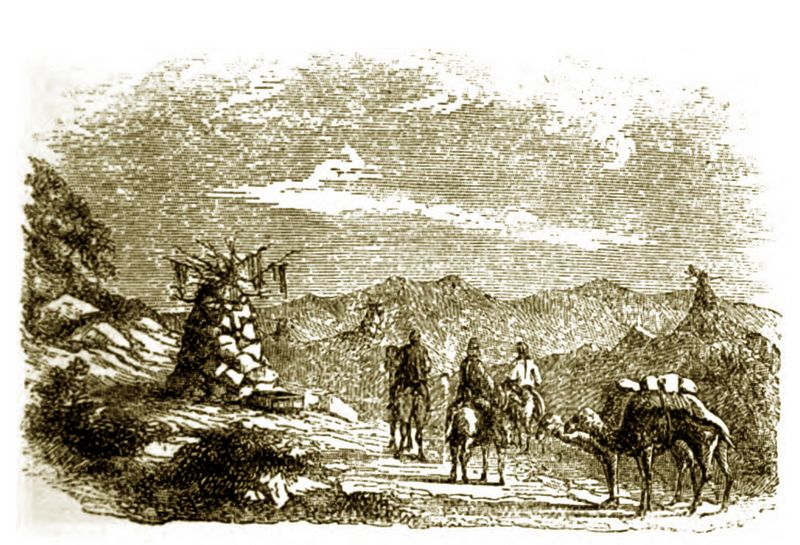

Fig.7: Mountain of Sain-Oula

The

mountain in question is called Sain-Oula (Good Mountain), doubtless ut

lucus a non lucendo, since it is notorious for the dismal accidents and

tragical adventures of which it is the theatre. The ascent is by

a rough, steep path, half-choked up with fallen rocks. (p.22)

Mid-way up is a small temple, dedicated to the divinity of the

mountain, Sain-Nai, (the good old Woman;) the occupant is a priest,

whose business it is, from time to time, to fill up the cavities in the

road, occasioned by the previous rains, in consideration of which

service he receives from each passenger a small gratuity, constituting

his revenue. After a toilsome journey of nearly three hours we

found ourselves at the summit of the mountain, upon an immense plateau,

extending from east to west a long day’s journey, and from north to

south still more widely. From this summit you discern, afar off

in the plains of Tartary, the tents of the Mongols, ranged

semi-circularly on the slopes of the hills, and looking in the distance

like so many bee-hives. Several rivers derive their source from

the sides of this mountain. Chief among these is the Chara-Mouren

(Yellow River—distinct, of course, from the great Yellow River of

China, the Hoang-Ho)—the capricious, course of which the eye can follow

on through the kingdom of Gechekten, after traversing which, and then

the district of Naiman, it passes the stake-boundary into Mantchouria,

and flowing from north to south, falls into the sea, approaching which

it assumes the name Léao-Ho.

The Good Mountain is noted for its

intense frosts. There is not a winter passes in which the cold

there does not kill many travellers. Frequently whole caravans,

not arriving at their destination on the other side of the mountain,

are sought and found on its bleak road, man and beast frozen to

death. Nor is the danger less from the robbers and the wild

beasts with whom the mountain is a favourite haunt, or rather a

permanent station. Assailed by the brigands, the unlucky

traveller is stripped, not merely of horse and money, and baggage, but

absolutely of the clothes he wears, and then left to perish from cold

and hunger.

Not but that the brigands of these parts are

extremely polite all the while; they do not rudely clap a pistol to

your ear, and bawl at you: “Your money or your life!” No; they

mildly advance with a courteous salutation: “Venerable elder brother, I

am on foot; pray lend me your horse—I’ve got no money, be good enough

to lend me your purse—It’s quite cold to-day, oblige me with the loan

of your coat.” If the venerable elder brother charitably

complies, the matter ends with, “Thanks, brother;” but otherwise, the

request is forthwith emphasized with the arguments of a cudgel; and if

these do not convince, recourse is had to the sabre.

Fig.8: First Encampment

Being novices

in travelling, the idea of robbers haunted us incessantly, and we took

everybody we saw to be a suspicious character, against whom we must be

on our guard. A grassy nook, surrounded by tall trees,

appertaining to the Imperial Forest, fulfilled our requisites.

Unlading our dromedaries, we raised, with no slight labour, our tent

beneath the foliage, and at its entrance installed our faithful porter,

Arsalan, a dog whose size, strength, and courage well entitled him to

his appellation, which, in the Tartar-Mongol dialect, means

“Lion.” Collecting some argols (p.23) and dry branches of trees,

our kettle was soon in agitation, and we threw into the boiling water

some Kouamien, prepared paste, something like Vermicelli, which,

seasoned with some parings of bacon, given us by our friends at

Yan-Pa-Eul, we hoped would furnish satisfaction for the hunger that

began to gnaw us. No sooner was the repast ready, than each of

us, drawing forth from his girdle his wooden cup, filled it with

Kouamien, and raised it to his lips. The preparation was

detestable—uneatable. The manufacturers of Kouamien always salt

it for its longer preservation; but this paste of ours had been salted

beyond all endurance. Even Arsalan would not eat the

composition. Soaking it p. 24for a while in cold water, we once

more boiled it up, but in vain; the dish remained nearly as salt as

ever: so, abandoning it to Arsalan and to Samdadchiemba, whose stomach

by long use was capable of anything, we were fain to content ourselves

with the dry-cold, as the Chinese say; and, taking with us a couple of

small loaves, walked into the Imperial Forest, in order at least to

season our repast with an agreeable walk. Our first nomade

supper, however, turned out better than we had expected, Providence

placing in our path numerous Ngao-la-Eul and Chan-ly-Houng trees, the

former, a shrub about five inches high, which bears a pleasant wild

cherry; the other, also a low but very bushy shrub, producing a small

scarlet apple, of a sharp agreeable flavour, of which a very succulent

jelly is made.

The Imperial Forest extends more than a hundred

leagues from north to south, and nearly eighty from east to west.

The Emperor Khang-Hi, in one of his expeditions into Mongolia, adopted

it as a hunting ground. He repaired thither every year, and his

successors regularly followed his example, down to Kia-King, who, upon

a hunting excursion, was killed by lightning at Ge-ho-Eul. There

has been no imperial hunting there since that time—now twenty-seven

years ago. Tao-Kouang, son and successor of Kia-King, being

persuaded that a fatality impends over the exercise of the chase, since

his accession to the throne has never set foot in Ge-ho-Eul, which may

be regarded as the Versailles of the Chinese potentates. The

forest, however, and the animals which inhabit it, have been no gainers

by the circumstance. Despite the penalty of perpetual exile

decreed against all who shall be found, with arms in their hands, in

the forest, it is always half full of poachers and woodcutters.

Gamekeepers, indeed, are stationed at intervals throughout the forest;

but they seem there merely for the purpose of enjoying a monopoly of

the sale of game and wood. They let any one steal either,

provided they themselves get the larger share of the booty. The

poachers are in especial force from the fourth to the seventh

moon. At this period, the antlers of the stags send forth new

shoots, which contain a sort of half-coagulated blood, called

Lou-joung, which plays a distinguished part in the Chinese Materia

Medica, for its supposed chemical qualities, and fetches accordingly an

exorbitant price. A Lou-joung sometimes sells for as much as a

hundred and fifty ounces of silver.

Deer of all kinds abound in

the forest; and tigers, bears, wild boars, panthers, and wolves are

scarcely less numerous. Woe to the hunters and wood-cutters who

venture otherwise than in large parties into the recesses of the

forest; they disappear, leaving no vestige behind.

p. 25The fear

of encountering one of these wild beasts kept us from prolonging our

walk. Besides, night was setting in, and we hastened back to our

tent. Our first slumber in the desert was peaceful, and next

morning early, after a breakfast of oatmeal steeped in tea, we resumed

our march along the great Plateau. We soon reached the great Obo,

whither the Tartars resort to worship the Spirit of the Mountain.

The monument is simply an enormous pile of stones, heaped up without

any order, and surmounted with dried branches of trees, from which hang

bones and strips of cloth, on which are inscribed verses in the Thibet

and Mongol languages.

At its base is a

large granite urn in which the devotees burn incense. They offer,

besides, pieces of money, which the next Chinese passenger, after

sundry ceremonious genuflexions before the Obo, carefully collects and

pockets for his own particular benefit.

These Obos, which occur

so frequently throughout Tartary, and which are the objects of constant

pilgrimages on the part of the Mongols, remind one of the loca excelsa

denounced by the Jewish prophets.

It was near noon before the

ground, beginning to slope, intimated that we approached the

termination of the plateau. We then descended rapidly into a deep

valley, where we found a small Mongolian encampment, which we passed

without pausing, and set up our tent for the night on the margin of a

pool further on. We p. 26were now in the kingdom of Gechekten, an

undulating country, well watered, with abundance of fuel and pasturage,

but desolated by bands of robbers. The Chinese, who have long

since taken possession of it, have rendered it a sort of general refuge

for malefactors; so that “man of Gechekten” has become a synonyme for a

person without fear of God or man, who will commit any murder, and

shrink from no crime. It would seem as though, in this country,

nature resented the encroachments of man upon her rights.

Wherever the plough has passed, the soil has become poor, arid, and

sandy, producing nothing but oats, which constitute the food of the

people. In the whole district there is but one trading town,

which the Mongols call Altan-Somé, (Temple of Gold). This was at

first a great Lamasery, containing nearly 2000 Lamas. By degrees

Chinese have settled there, in order to traffic with the Tartars.

In 1843, when we had occasion to visit this place, it had already

acquired the importance of a town. A highway, commencing at

Altan-Somé, proceeds towards the north, and after traversing the

country of the Khalkhas, the river Keroulan, and the Khinggan

mountains, reaches Nertechink, a town of Siberia.

The sun had

just set, and we were occupied inside the tent boiling our tea, when

Arsalan warned us, by his barking, of the approach of some

stranger. We soon heard the trot of a horse, and presently a

mounted Tartar appeared at the door. “Mendou,” he exclaimed, by

way of respectful salutation to the supposed Lamas, raising his joined

hands at the same time to his forehead. When we invited him to

drink a cup of tea with us, he fastened his horse to one of the

tent-pegs, and seated himself by the hearth. “Sirs Lamas,” said

he, “under what quarter of the heavens were you born?” “We are

from the western heaven; and you, whence come you?” “My poor

abode is towards the north, at the end of the valley you see there on

our right.” “Your country is a fine country.” The Mongol

shook his head sadly, and made no reply. “Brother,” we proceeded,

after a moment’s silence, “the Land of Grass is still very extensive in

the kingdom of Gechekten. Would it not be better to cultivate

your plains? What good are these bare lands to you? Would

not fine crops of corn be preferable to mere grass?” He replied,

with a tone of deep and settled conviction, “We Mongols are formed for

living in tents, and pasturing cattle. So long as we kept to that

in the kingdom of Gechekten, we were rich and happy. Now, ever

since the Mongols have set themselves to cultivating the land, and

building houses, they have become poor. The Kitats (Chinese) have

taken possession of the country; flocks, herds, lands, houses, all have

passed into their hands. There remain to us only a few prairies,

on which still live, under their tents, such of the (p.27) Mongols as

have not been forced by utter destitution to emigrate to other

lands.” “But if the Chinese are so baneful to you, why did you

let them penetrate into your country?” “Your words are the words

of truth, Sirs Lamas; but you are aware that the Mongols are men of

simple hearts. We took pity on these wicked Kitats, who came to

us weeping, to solicit our charity. We allowed them, through pure

compassion, to cultivate a few patches of land. The Mongols

insensibly followed their example, and abandoned the nomadic

life. They drank the wine of the Kitats, and smoked their

tobacco, on credit; they bought their manufactures on credit at double

the real value. When the day of payment came there was no money

ready, and the Mongols had to yield, to the violence of their

creditors, houses, lands, flocks, everything.” “But could you not

seek justice from the tribunals?” “Justice from the

tribunals! Oh, that is out of the question. The Kitats are

skilful to talk and to lie. It is impossible for a Mongol to gain

a suit against a Kitat. Sirs Lamas, the kingdom of Gechekten is

undone!” So saying, the poor Mongol rose, bowed, mounted his

horse, and rapidly disappeared in the desert.

We travelled two

more days through this kingdom, and everywhere witnessed the poverty

and wretchedness of its scattered inhabitants. Yet the country is

naturally endowed with astonishing wealth, especially in gold and

silver mines, which of themselves have occasioned many of its worst

calamities. Notwithstanding the rigorous prohibition to work

these mines, it sometimes happens that large bands of Chinese outlaws

assemble together, and march, sword in hand, to dig into them.

These are men professing to be endowed with a peculiar capacity for

discovering the precious metals, guided, according to their own

account, by the conformation of mountains, and the sorts of plants they

produce. One single man, possessed of this fatal gift, will

suffice to spread desolation over a whole district. He speedily

finds himself at the head of thousands and thousands of outcasts, who

overspread the country, and render it the theatre of every crime.

While some are occupied in working the mines others pillage the

surrounding districts, sparing neither persons nor property, and

committing excesses which the imagination could not conceive, and which

continue until some mandarin, powerful and courageous enough to

suppress them, is brought within their operation, and takes measures

against them accordingly.

Fig.10: Military Mandarin

One day, however, the

Queen of Ouniot, repairing on a pilgrimage to the tomb of her

ancestors, had to pass the valley in which the army of miners was

assembled. Her car was surrounded; she was rudely compelled to

alight, and it was only upon the sacrifice p. 29of her jewels that she

was permitted to proceed. Upon her return home, she reproached

the King bitterly for his cowardice. At length, stung by her

words, he assembled the troops of his two banners, and marched against

the miners. The engagement which ensued was for a while doubtful;

but at length the miners were driven in by the Tartar cavalry, who

massacred them without mercy. The bulk of the survivors took

refuge in the mine. The Mongols blocked up the apertures with

huge stones. The cries of the despairing wretches within were

heard for a few days, and then ceased for ever. Those of the

miners who were taken alive had their eyes put out, and were then

dismissed.

We had just quitted the kingdom of Gechekten, and

entered that of Thakar, when we came to a military encampment, where

were stationed a party of Chinese soldiers charged with the

preservation of the public safety. The hour of repose had

arrived; but these soldiers, instead of giving us confidence by their

presence, increased, on the contrary, our fears; for we knew that they

were themselves the most daring robbers in the whole district. We

turned aside, therefore, and ensconced ourselves between two rocks,

where we found just space enough for our tent. We had scarcely

set up our temporary abode, when we observed, in the distance, on the

slope of the mountains, a numerous body of horsemen at full

gallop. Their rapid but irregular evolutions seemed to indicate

that they were pursuing something which constantly evaded them.

By-and-by, two of the horsemen, perceiving us, dashed up to our tent,

dismounted, and threw themselves on the ground at the door. They

were Tartar-Mongols. “Men of prayer,” said they, with voices full

of emotion, “we come to ask you to draw our horoscope. We have

this day had two horses stolen from us. We have fruitlessly

sought traces of the robbers, and we therefore come to you, men whose

power and learning is beyond all limit, to tell us where we shall find

our property.” “Brothers,” said we, “we are not Lamas of Buddha;

we do not believe in horoscopes. For a man to say that he can, by

any such means, discover that which is stolen, is for them to put forth

the words of falsehood and deception.” The poor Tartars redoubled

their solicitations; but when they found that we were inflexible in our

resolution, they remounted their horses, in order to return to the

mountains.

Samdadchiemba, meanwhile, had been silent, apparently

paying no attention to the incident, but fixed at the fire-place, with

his bowl of tea to his lips. All of a sudden he knitted his

brows, rose, and came to the door. The horsemen were at some

distance; but the Dchiahour, by an exertion of his strong lungs,

induced them to turn round in their saddles. He motioned to them,

and they, supposing p. 30we had relented, and were willing to draw the

desired horoscope, galloped once more towards us. When they had

come within speaking distance:—“My Mongol brothers,” cried

Samdadchiemba, “in future be more careful; watch your herds well, and

you won’t be robbed. Retain these words of mine on your memory:

they are worth all the horoscopes in the world.” After this

friendly address, he gravely re-entered the tent, and seating himself

at the hearth, resumed his tea.

We were at first somewhat

disconcerted by this singular proceeding; but as the horsemen

themselves did not take the matter in ill part, but quietly rode off,

we burst into a laugh. “Stupid Mongols!” grumbled Samdadchiemba;

“they don’t give themselves the trouble to watch their animals, and

then, when they are stolen from them, they run about wanting people to

draw horoscopes for them. After all, perhaps, it’s no wonder, for

nobody but ourselves tells them the truth. The Lamas encourage

them in their credulity; for they turn it into a source of

income. It is difficult to deal with such people. If you

tell them you can’t draw a horoscope, they don’t believe you, and

merely suppose you don’t choose to oblige them. To get rid of

them, the best way is to give them an answer haphazard.” And here

Samdadchiemba laughed with such expansion, that his little eyes were

completely buried. “Did you ever draw a horoscope?” asked

we. “Yes,” replied he still laughing. “I was very young at

the time, not more than fifteen. I was travelling through the Red

Banner of Thakar, when I was addressed by some Mongols who led me into

their tent. There they entreated me to tell them, by means of

divination, where a bull had strayed, which had been missing three

days. It was to no purpose that I protested to them I could not

perform divination, that I could not even read. ‘You deceive us,’

said they; ‘you are a Dchiahour, and we know that the Western Lamas can

all divine more or less.’ As the only way of extricating myself

from the dilemma, I resolved to imitate what I had seen the Lamas do in

their divinations. I directed one person to collect eleven

sheep’s droppings, the dryest he could find. They were

immediately brought. I then seated myself very gravely; I counted

the droppings over and over; I arranged them in rows, and then counted

them again; I rolled them up and down in threes; and then appeared to

meditate. At last I said to the Mongols, who were impatiently

awaiting the result of the horoscope: ‘If you would find your bull, go

seek him towards the north.’ Before the words were well out of my

mouth, four men were on horseback, galloping off towards the

north. By the most curious chance in the world, they had not

proceeded far, before the missing animal made its appearance, quietly

browzing. I at once got the character (p.31) of a diviner of the

first class, was entertained in the most liberal manner for a week, and

when I departed had a stock of butter and tea given me enough for

another week. Now that I belong to Holy Church, I know that these

things are wicked and prohibited; otherwise I would have given these

horsemen a word or two of horoscope, which perhaps would have procured

for us, in return, a good cup of tea with butter.”

The stolen

horses confirmed in our minds the ill reputation of the country in

which we were now encamped; and we felt ourselves necessitated to take

additional precaution. Before night-fall we brought in the horse

and the mule, and fastened them by cords to pins at the door of our

tent, and made the camels kneel by their side, so as to close up the

entrance. By this arrangement no one could get near us without

our having full warning given us by the camels, which, at the least

noise, always make an outcry loud enough to awaken the deepest

sleeper. Finally, having suspended from one of the tent-poles our

travelling lantern, which we kept burning all the night, we endeavoured

to obtain a little repose, but in vain; the night passed away, without

our getting a wink of sleep. As to the Dchiahour, whom nothing

ever troubled, we heard him snoring with all the might of his lungs

until daybreak.

We made our preparations for departure very

early, for we were eager to quit this ill-famed place, and to reach

Tolon-Noor, which was now distant only a few leagues.

On our way

thither, a horseman stopped his galloping steed, and, after looking at

us for a moment, addressed us: “You are the chiefs of the Christians of

the Contiguous Defiles?” Upon our replying in the affirmative, he

dashed off again; but turned his head once or twice, to have another

look at us. He was a Mongol, who had charge of some herds at the

Contiguous Defiles. He had often seen us there; but the novelty

of our present costume at first prevented his recognising us. We

met also the Tartars who, the day before, had asked us to draw a

horoscope for them. They had repaired by daybreak, to the

horse-fair at Tolon-Noor, in the hope of finding their stolen animals;

but their search had been unsuccessful.

With the exception of these few esculents, the

environs of Tolon-Noor produce absolutely nothing whatever. The

soil is dry and sandy, and water terribly scarce. It is only here

and there that a few limited springs are found, and these are dried up

in the hot season.

Footnotes:

[Continue to Chapter 2]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|