| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

The Royal Tombs of the First Dynasty (Abydos), Part I W.E. Flinders Petrie | | | | |

|

THE ROYAL TOMBS OF THE FIRST DYNASTY, PART I.

Chapter 2

DESCRIPTION OF THE TOMBS (Sections 8-19; Plates 60-67).

8.

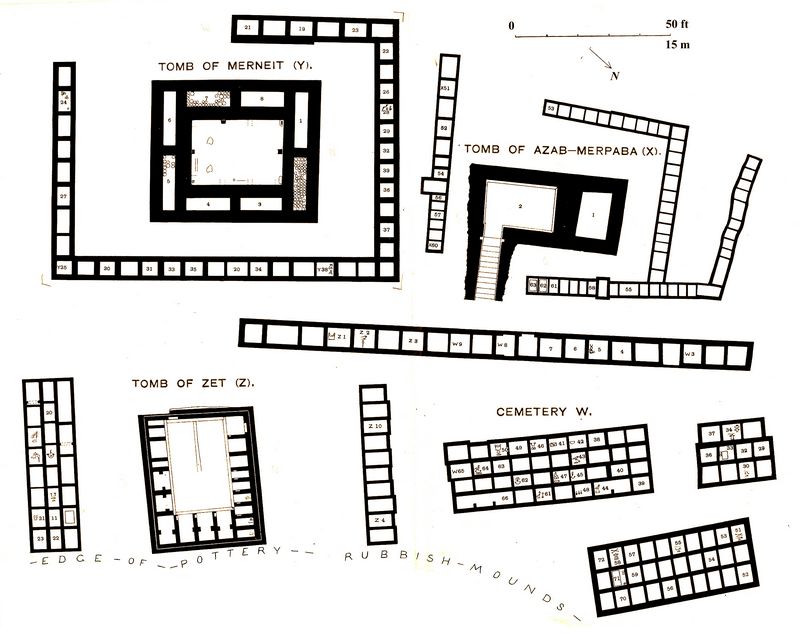

The Tomb of Zet, pl.61. This tomb consists of a large chamber twenty

feet wide and thirty feet long, with smaller chambers around it at its

level, the whole bounded by a thick brick wall, which rises seven and a

half feet to the roof, and then three and a half feet more to the top

of the retaining wall. The exact dimensions of these tombs are all

given together in sect.19. Outside of this on the north is a line of

small tombs about five feet deep, and on the south a triple line of

tombs of the same depth. And apparently of the same system and same age

is the mass of tombs marked as “Cemetery W," which are parallel to the

tomb of Zet. Later there appears to have been built the long line of

tombs which arc marked partly Z, partly W, placed askew in order not to

interfere with those which have been mentioned. And then this skew line

gave the direction to the next tomb, that of Merneit, and later on that

of Azab. Such seems to have been the order of construction; but as the

great mounds of rubbish, which I have not yet moved, stand close to the

east of Zet and Cemetery W, there may be other features beneath them

which will further explain the arrangement.

Plate 61: Plans of tombs of Merneit, Azab, and Zet, and Cemetery W.

The private graves around the royal tomb are all

built of mud brick, with a coat of mud plaster over it, and the floor

is of sand, usually also coated with mud. The steles found in the

graves around Zet are shown in pls.33, 34, and the copies pl.31, Nos.

1-16. The places of such as could be at all identified with the graves,

are shown on pl.61 by the name from each being written on the chamber

plan. Beside these steles there were often the names inscribed in red

paint on the walls; these names are drawn in pl.63, and are written

close to the south wails of the plans. These painted names are always

on the south wall of the chamber, close to the top of it. A patch of

whitewash about eight or ten inches square was roughly brushed on the

mud plaster of the wall; on that the hieroglyphs were painted with a

broad brush. Some lines are pink, owing to the whitewash working up

with the red in the brush. On a few are traces of black also. The form

of inscription is much simpler than that of the steles; the ka akh,

"glorified ka," only once appears, and there are no titles or offices,

only the name. The ka arms often appear; but whether this refers to the

ka of Du, A, Si, etc., or is really a compound name, Ka-du, A-kat,

Si-ka, is not clear. Probably the latter is true, as the feminine t is

added to the ha in two cases, which points to its being in a name. Many

of these names were illegible, only fragments of the plaster remaining.

Three I succeeded in removing. The few contents of these graves, left

behind accidentally by previous diggers, will be fully catalogued in

the next Volume; a few jars and beads, and two or three pieces of

inscribed stone bowls (each marked with their source in pls.4 and 6),

are all that we found.

Plate 62: Section and detailed plan of the west end of the Tomb of King Zet.

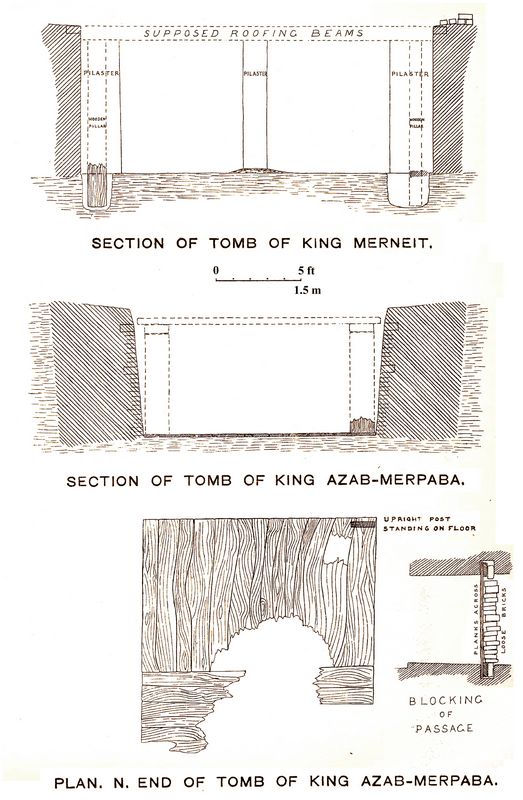

9. Tomb of Zet, interior, pls.61, 62, 63. The first

question about these great tombs is how they were covered over. Some

have said that such spaces could not be roofed, (p.9) and at first

sight it would seem almost impossible. But the actual beams found yet

remaining in the tombs are as long as the widths of the tombs, and

therefore timber of such sizes could be procured. In the tomb of Qa the

holes for the beams yet remain in the wails, and even the cast of the

end of a beam. And in the tombs of Merneit, Azab, and Mersekha are

posts and pilasters to help in supporting a roof.

We must

therefore see how far such a roof would be practicable. The clear span

of the chamber of Zet is 240 inches, or 220 if the beams were carried

on a wooden lining, as seems likely. Taking, however, 240 inches

length, and a depth and breadth of 10 inches like the breadths of the

floor beams, such a beam of a conifer, supported at both ends and

uniformly loaded, would carry about 51,000 lbs., or 2900 lbs. on each

foot of roof area. This is equal to 33 feet depth of dry sand. Hence,

even if the great beams were spaced apart with three times their

breadth between each, they would carry eight feet depth of sand on

them; but as the height of the retaining wail is 3 1/2 feet, the strain

would be only half of the full load.

It is therefore quite practicable to roof over these

great chambers up to spans of twenty feet. The wood of such lengths was

actually used, and if spaced out over only a quarter of the area, the

beams would carry their load with full safety. Any boarding, mats,

straw etc. laid over the beams would not increase the load, as they

would be lighter than the same bulk of sand. That there was a mass of

sand laid over the tomb is strongly shown by the retaining wail (see

pl.62) around the top. This wall is roughly built, not intended to be a

visible feature. The outside is daubed with mud plaster, and has a

considerable slope; the inside is left quite rough, with bricks in and

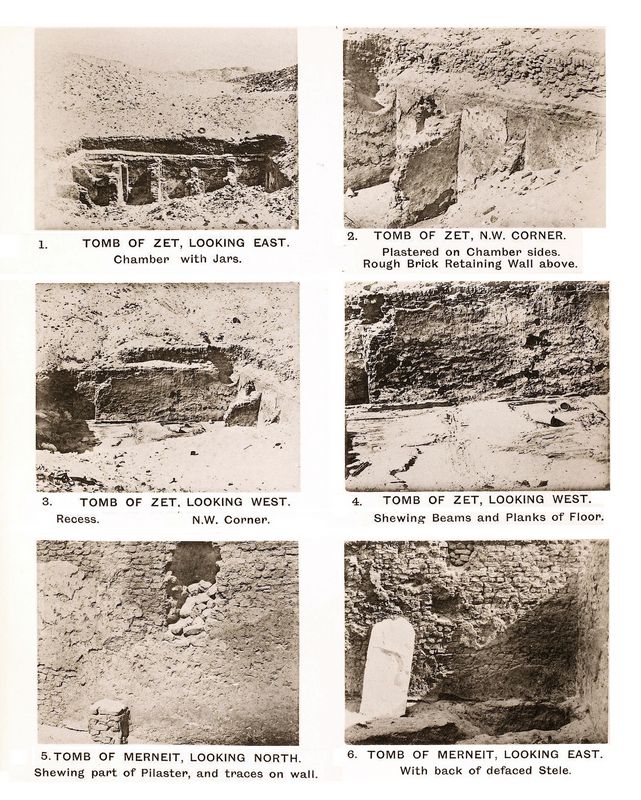

out (see photographs on pl.64, Nos. 1, 2, 3). Such a construction shows

that it was backed against loose material inside it. The top of it is

finished off with a rough rounding. At the S.W. corner this retaining

wail ceases, and it seems as if this were left thus in order to gain

access to the tomb for the funeral. The full thickness of the tomb wail

stretches out several feet beyond even the outside of the upper

retaining wall.

Plate 64: Views of the Tombs of Kings Zet and Merneit.

Turning now to the floor, the section is

given in pl.62, and the view of it in photographs pl.64, nos. 3, 4. The

basis of it is mud plastering, which was whitewashed. On that were laid

beams around the sides, and one down the middle: these beams were

between 9 and 10.8 inches wide, and 7 to 7 1/2 inches deep. They

were placed before the mud floor was hard, and have sunk about

1/4 inch into it. On the beams a ledge was recessed 6.5 to

7.7 wide, and 4.7 to 6.0 deep. On this ledge the edges of the

flooring planks rested, 2 to 2.4 thick. Such planks would not

bend 1/4 inch in the middle by a man standing on them, and

therefore made a sound floor. Over the planks was laid a coat of mud

plaster .5 to .7 inch thick. This construction doubtless shows what was

the mode of flooring the palaces and large houses of the early

Egyptians, in order to keep off the damp of the ground in the Nile

valley. For common houses a basis of pottery jars turned mouth

down was used for the same purpose, as I found at Koptos.

The sides of the great central chamber are not clear in

arrangement. The brick cross walls which subdivide them into

separate cells have no finished faces on their ends. All the wall faces

are plastered and whitewashed; but the ends of the cross wails are

rough bricks, all irregularly in and out. Moreover, the bricks project

forward irregularly over the beam line, as outlined in the plan, pl.62.

This projection is 4 inches on the north, 4 on the east, and 2 1/2 on

the south; and on the east, one of the overhanging bricks had mud on

the end of it, with a cast of upright timber on it. It seems then

that there was an upright timber lining to the chamber, against which

the cross walls were (p.10) built, the walls thus having rough ends

projecting over the beams. The footing of this upright plank

lining is indicated by a groove left along the western floor beam, 3.7

wide between the ledge on the beam and the side of the flooring planks

(see plan pl.62). Thus we reach the view of a wooden chamber, lined

with upright planks 3 1/2 inches thick, which stood 3 to 4 inches out

from the wall, or from the backs of the beams. How the side chambers

were entered is not shown; whether there was a door to each or no. But

as they were intended to be forever closed, and as the chambers in two

corners were shut off by brickwork all round, it seems likely that all

the side chambers were equally closed. And thus, after the slain

domestics (p. 1.4) and offerings were deposited in them, and the king

in the centre hall, the roof would be permanently placed over the

whole.

The height of the chamber is proved by the cast of

straw which formed part of the roofing, and which comes at the

top of the course of headers on edge which copes the wall all

round the chamber. Over this straw there was laid one course of

bricks a little recessed, and beyond that is the wide ledge all round

before reaching the retaining wall. The height up to the top of this

course of headers is 89.6 in N.W. chamber, = 90.6 in main chamber, as

the floor is 1 inch higher; 93.2 in second chamber N., = 94.2 in main;

90.0 in third chamber S., = 91.0 in main; and 95.3 on mid W. So it

varies from 90.6 to 95.3 over the main mud floor. This implies about

92, less 4 for flooring, less probably 12 for roofing, or clear 76

inches height in the chamber. The retaining wall is 38 inches high

inside, and 47 high outside.

Having thus cleared

up the central chamber, we should notice those at the sides. The cross

walls were built after the main brick outside was finished and

plastered. The deep recesses coloured red, on the north side (see

pl.63), were built in the construction; where the top is preserved

entire, as in a side chamber on the north, it is seen that the roofing

of the recess was upheld by building in a board about an inch

thick. The shallow recesses along the south side were merely made in

the plastering, and even in the secondary plastering after the

cross walls were built. All of these recesses, except that at the S.W.,

were coloured pink red, due to mixing burnt ochre with the white. In

the outlines of pl.63 the condition of the walls does not profess to be

exactly as at present, but more or less broken down, so as to show the

plan and detail more clearly. The purport of these recesses is quite

unknown; but they can hardly be separated from the red recesses on the

walls of the central halls of houses at Tell el Amarna, of the XVIII

Dynasty. There was also a red recess, with a scene of worship of the

tree goddess painted over it, in a gallery of the Hamesseum. It seemed

from that as if these red recesses were false doorways for the worship

of domestic spirits. Possibly this may be connected with the red

recesses of this tomb. The supposition that these recesses were to hold

steles is impossible, in view of the sizes of the steles, and the

finishing and colouring of the recesses.

10.

The Tomb of Merneit, pls.61,64,65. This tomb was not at first

suspected, as it had no accumulation of pottery over it; and the whole

ground had been pitted all over by the Mission Amelineau making

“quelques sondages," without revealing the chambers or the plan.

As soon, however, as we began to systematically clear the ground the

scheme of a large central chamber with eight long chambers for

offerings around it, and a line of private tombs enclosing it, stood

apparent. The central chamber is very accurately built, with vertical

sides parallel to less than an inch. It is about 21 feet wide and 30

feet long, or practically the same as the chamber of Zet (exactly 250 X

354 inches to the brick walls, the plaster varying from ¼ to 1 inch).

Around the chamber are walls 48 to 52 inches thick, and beyond (p.11)

them a girdle of long narrow chambers, 48 wide and 160 to 215 inches

long. These chambers are about 6 1/2 feet deep, but the central chamber

is nearly 9 feet. Of these chambers for offerings Nos. 1, 2, 5, 7 still

contained pottery in place, and No.3 contained many jar stealings. The

great stele of Merneit (pl.00) was found lying near the east side of

the central chamber; and near it was the back of a similar stele (see

photograph, pl.64, No.6), on which the bottom of the neit and r signs

remained, and from which a piece of the top with the top of the

neit on it was found lying over chamber 5.

At a few

yards distance from the chambers full of offerings is a line of private

graves almost surrounding the royal tomb. This line is interrupted at

the S. end of the W. side, similar to the interruption of the retaining

wall of the tomb of Zet at that quarter. It seems therefore that the

funeral approached it from that direction. In the small graves there

are no red inscriptions, as in those belonging to Zet; but steles were

found, the names of two of which are entered on the plan, and the

figures are given in pls.31 and 34 Nos.17-19. A feature which

could not well be shown in the plan is the ledge which runs along

the side of these tombs. The black wall here figured is the width of

the level edge of the pit, but beyond this a slight edging of brick

rises a few inches higher.

11. The Tomb of

Merneit, interior, pls.64 and 65. The chamber shows signs of burning,

on both the walls and the floor. A small piece of wood yet remaining on

the floor indicates that it also had a wooden floor, like the other

tombs. Against the walls stand pilasters of brick (see plan 61,

photograph 64, No.5); and though these are not at present more

than a quarter of the whole height of the wall, they

originally reached to the top, as is shown by the smoking of the wall

on each side, even visible in the photograph. These pilasters are

entirely additions to the first building; they stand against the

plastering, and upon a loose layer of sand and pebbles about 4 inches

thick. Thus it is clear that they belong to the subsequent stage

of the fitting of a roof to the chamber. Such a roof would not need to

be as strong as that of Zet, as there was much less depth of sand over

it; so that beams only at the pilasters would serve to carry enough

boards to cover it. The pilasters, however, seem to have been

altogether an afterthought, as within two of the corner ones there

remain the ends of upright posts, around which the brickwork was

built. The holes that are shown in the floor are apparently not

connected with the construction, as they are not in the mid-line where

pillars are likely. The height of the chamber is 105 inches, at both E.

and S.W., up to the top of a course of headers on edge around it.

At the edge of chamber 2 is the cast of plaited palm-leaf matting on

the mud mortar above this level, and the bricks are set back

irregularly; this shows the mode of finishing off the roof of this

tomb.

12. The Tomb of Den-Setui, pl.59. From the

position of this tomb it is seen to naturally follow the building of

the tombs of Zet and Merneit. It is surrounded by rows of small

chambers, for offerings, and for burial of domestics; but as I have

only partially examined these as yet, no plan in detail is here given.

The king's tomb appears to have contained a great number of tablets of

ivory and ebony, fragments of eighteen having been found by

us in the rubbish thrown out by the Mission Amelineau, beside one

perfect tablet stolen from that work (now in the MacGregor collection),

and a piece picked up (now in Cairo Museum); thus twenty tablets are

known from this tomb. The inscriptions on stone vases (pl.5) are,

however, not more frequent than in previous reigns. This tomb appears

to be one of the most costly and sumptuous, with its pavement of red

granite; the details of it I hope to publish after its clearance next

season.

Plate 65: Tombs of King Merneit and Azab-Merpaba.

Around this tomb is a circuit of small private tombs,

leaving a gap on the S.W. like that of Merneit, and an additional

branch line has been added on at the north. All of these tombs are very

irregularly built; the sides are wavy in direction, and the divisions

of the long trench are slightly piled up, of bricks laid lengthways,

and easily overthrown. This agrees with the rough and irregular

construction of the central tomb and offering chamber. The funeral of

Azab seems to have been more carelessly conducted than that of any of

the other kings here; only one piece of inscribed vase was in his tomb,

as against eight of his found in his successor's tomb, and many

other vases of his erased by his successor. Thus his palace property

seems to have been kept back for his successor's use, and not buried

with Azab himself. In the chambers 58, 61, 62, 63 much ivory inlaying

was found, figured in pl.37, Nos.47—60. All the tomb contents will be

fully described in a future volume.

14. The Tomb of Azab, interior, pls.65 and 66. The

entrance to the tomb was by a stairway descending from the east, thus

according with the system begun by the previous king, Den. Each step is

about twenty inches wide and eight inches high; and thus descending ten

steps we reach the blocking of the doorway. On these steps, just

outside of the door, were dozens of small pots, loosely piled together,

of the forms marked Y in pls.42 and 43. These must have contained

offerings made after the completion of the burial. The blocking is made

by planks and bricks (sec pl.65, lower right hand). Two grooves were

left in the brickwork of the passage sides, plastered over like the

passage. Across the passage stretched planks of wood about two inches

thick, with ends lodging in the grooves. To retain them in place on

each other another upright plank was placed against them in the groove,

and jammed tight by bricks wedged in. Then the whole outside of

the planking was covered by bricks loosely stacked as headers; these

can be seen in the photograph (pl.66, No.2), the planking having

decayed away from before them.

The chamber was floored

with planks of wood laid flat on the sand, without any supporting beams

as in other tombs. These planks are 2.0 inches thick where best

preserved. They were cut to order before fitting into the tomb,

and hence in several places they were slightly too long. This has been

roughly remedied by chopping away the mud wall near the bottom so as to

let in the ends (see pl.66, No.1), or scraping down so as to jam the

board down into place.

The support of the roof was by wooden

posts, as in the tomb of Merneit; but here they were not cased round or

supplemented by brick piers. The base of one post remained in place at

the N.E. corner (see pl.65): it was 4 X 17 inches, and stood free on

the floor, not let in at all, 3 inches from the N. and 1 inch from the

E. sides. That this was not accidental in place is shown at the N.W.

corner, where the N. wall has been much chopped away in order to let

back an irregularly bent post. Beyond this there are no traces, either

from attachment or from burning, of uprights or divisions, or of

pilasters on the walls.

(p.13) The roof must have been about six

feet over the floor, as the walls are finished up to 78 inches high,

and then are rougher and more sloping above that. The plastering went

on simultaneously with the building: this is shown by a course of

headers on edge at 48 inches, up to which the plastering has been

done at once, while above that the plastering was separate. The

highest part of the wail is 89 inches high, the ground at the top step

being 97 inches. The roof broke in at the middle of the south end, and

let sand run in enough to fill the chamber at that end. Thus only the

two corners were left exposed to the fire in the burning of the

roof.

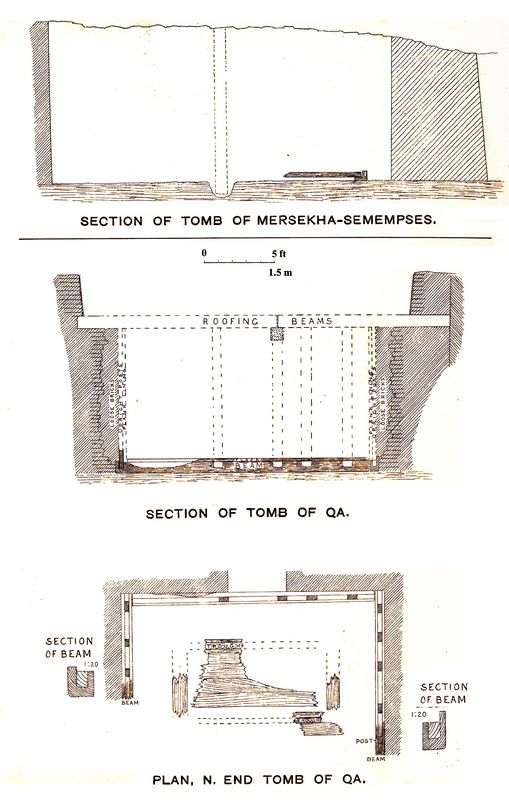

15. The Tomb of Mersekha-Semempses, pl.60. This

tomb is 44 feet long and 25 feet wide, a pit surrounded by a wall over

five feet thick. The surrounding small chambers are only three to four

feet deep, where perfect; while the central pit is still 11 1/2 feet

deep, though broken away at the top.

Few of the small

chambers still contained anything. Seven steles were found, the

inscriptions of which are marked in the chambers of the plan: the

photographs, pls.35 and 36, show these in Nos. 29, 30, 31, 32, 35, 36,

46; and other steles on these plates were also found here, scattered so

that they could not be identified with the tombs. The most interesting

are two steles of dwarfs, 36, 37, which show the dwarf type clearly;

with one (chamber M) were found bones of a dwarf. Another skeleton of a

dwarf was in chamber L; probably the other stele had belonged to this.

In a chamber on the east was a jar and a copper bowl (pl.12, No.11);

this last is the only large piece of metalwork that we found; it

shows the hammer marks, and is roughly finished, with the

edge turned over to leave it smooth. We here have a good example

of the rude state of metal-work at that time. The ivory leg of a casket

(pl.12, No.9) was found loose in the rubbish before the door-way of the

tomb, and had doubtless been part of the royal furniture. The small

compartments in the south-eastern chambers were probably intended to

hold the offerings placed in the graves: the dividing walls are only

about half the depth of the grave.

Plate 60: Plans of the Tombs of King Qa and Mersekha-Semempses.

16. The Tomb of Mersekha, exterior, pls.60, 61, and 62.

The structure of the interior is at present uncertain. Only in the

corner by the entrance (pl.66, No.4) was the wooden flooring preserved:

several beams (one now in Cairo Museum) and much broken wood was

found loose in the rubbish. M. Amelineau states that the tomb was

entirely burnt, and the floor carbonized, but there are few traces of

fire about the wails. The floor, where it yet remains, is made like

others; beams, 8 inches wide and 10 high, form the frame on which the

planks of the floor rest on recessed ledges (see pls.60 and 67). There

has been a wider and shallower cutting also at each side of the corner,

as if some skin of finer wood had been laid over it. The corner plank

has two holes through it, and the sign meht, "north" cut on it. This

shows that the woodwork was prepared else-where, and brought here

ready; and this was also seen in the tomb of Azab, by the chopping of

the walls to fit the wood. This piece of floor is not symmetrically

placed, being 50 inches from the N. end, and so agreeing nearly

to the 56 inches projection of the pilaster at the S. end (see

pl.66, No.3), whereas it is only 19 inches from the entrance

wall. At about a third of the length from the S. end was a soft hole in

the sand floor, which may be the place of a pillar. The span of 24 feet

is too great to suppose it roofed with single beams across, and the

pilaster at the S. end suggests that the beams were supported or

divided in the middle. Hence it seems likely that the places of

the main beams were about the lines dotted in the plan, pl.60. There is

no sign of holes for the beams, and no evidence as to the roofing

level.

The entrance is 9 feet wide, and was blocked by

loose bricks, flush with wall face, as seen in (p.14) the photograph of

pl.64, No.4. Another looser walling further out, also seen in the

photograph, is probably that of plunderers to hold back the sand. The

section of the side wall of the entrance is given on pl.67.

On

clearing the entrance, the native hard sand was found to slope down to

about four feet above the floor, and then to drop to floor level

at about two and a half feet outside of the outer wall of the

tomb. Here the space was filled to three feet deep with sand saturated

with ointment. The fatty matter was that so common in the prehistoric

times, in this 1st Dynasty, and onward in the XVIII Dynasty;

hundredweights of it must have been poured out here, and the scent was

so strong when cutting away this sand that it could be smelt over the

whole tomb. In clearing this entrance was found the perfect ivory

tablet of king Semempses (pl.12, No.1 and pl.17, No.26); and his

identity with the king Mersekha of this tomb was proved by the sealing

No.72, pl.28.

17. The Tomb of King Qa, pls.60, 66, 67.

This tomb, which is the last of the Dynasty, shows a more developed

stage than the others. Chambers for offerings are built on each side of

the entrance passage, and this passage is turned to the north, as in

the mastabas of the III Dynasty, and in the pyramids. The

whole of the building is hasty and defective. The bricks were

mostly used too new, probably less than a week after being made. Hence

the walls have seriously collapsed in most of the lesser chambers; only

the one great chamber was built of firm and well-dried bricks. In the

four chambers along the passage, l6, 18, 23, 24, the walls have had to

be strengthened by thickening them, so as to leave wide ledges near the

top, shown by the outlines in the plan: in chamber 23 the south side

had crushed forward with its weight, and so taken a slice off the

chamber width. And the wall had slipped away sideways into chamber 12,

and was thus left ruined. In the small chambers along the east side the

long wall between chambers 10 and 5 has crushed out at the base, and

spread against the pottery in the grave 5, and against the

wooden box in grave 2. Hence the objects must have been placed in those

graves within a few days of the building of the wall, before the mud

bricks were hard enough to carry even four feet height of wall. The

burials of the domestics must therefore have taken place all at once,

immediately the king's tomb was built; and hence they must have been

sacrificed at the funeral.

The graves still contained

several burials, and these are all figured in position on the plan;

five have the head to the north, and only one to the south; all

are contracted. Thus the attitude was that of the prehistoric burials,

also found in the III Dynasty at Medum, and in the V Dynasty at

Deshasheh. But the direction is that of the historic burials. Hence the

customs have a greater break between the prehistoric and the 1st than

between the 1st and the V Dynasty. The boxes in which the bodies were

placed vary from 36 to 45 inches long, and 18 to 27 inches wide; the

average is 38 x 22. The height is usually 16 or 17 inches, in one case

only 9 inches. The boards are 1.2 inches thick. The sides appeared to

have been slightly pegged together, and they were found as merely

loose boards much decayed. The interior and space around the coffin

were filled with perfectly clean white sand, which must have been

intentionally filled in. But the coffins can hardly have been

made separately to fit the bodies; in grave 8 the body is bent

back-outward, naturally, but the head has been twisted round so as to

bring the face to the back; perhaps it was actually cut off, as

the atlas was an inch beyond the foramen.

There

were no personal ornaments or armlets found in any grave, though I

carefully cleared every coffin myself. The pottery placed in the

chambers is all figured in position in the plan; and the forms will be

seen, with the references to (p.15) the chambers, in pls.40 to 43. In

the S.E corner of chamber 9 were some baskets, of which one and part of

another could be removed.

Few steles were found, only

three in all, but these were larger than those of the earlier graves.

One is hardly legible (pl.31 and 36, No.47), being faintly hammered on

the stone face; it shows the hare un, and nothing else is

certain. The other stele, No. 48, is the longest and most

important inscription known of this age; it is carefully reproduced on

pl.30. The general surface is hammered out, but has never been finished

by graving; the full lines are the traces of the black ink drawing, and

the red lines show the first sketch. The description of it is given

more fully in dealing with the private steles, sect. 20. The stele of

the king Qa was found lying over chamber 3; it is like that found by M.

Amelineau, carved in black quartzose stone. Photographs have not yet

been taken of it, so it will be reproduced in the following volume.

Near it, on the south, were dozens of large pieces of fine alabaster

bowls, and one of diorite with the inscription for the "Priest of the

temple of King Qa" (ix. 12), showing that the shrine of offerings for

Qa was probably on this side.

Among various objects found

in these chambers should be noted the fine ivory carving from chamber

23, showing a bound captive (pl.12, Nos.12,13; pl.17, No.30), described

on p.23; the large stock of painted model vases in limestone in a box

in chamber 20 (pl.38, Nos.5,6); the set of perfect vases found in

chamber 21 (pl.38. No.8); the fine piece of ribbed ivory (pl.37,

No.79); a piece of thick gold foil covering of a hotep table, patterned

as a mat, found in the long chamber west of the tomb; the deep mass of

brown vegetable matter in the N.E. chamber; the large stock of corn

between chambers 8 and 11; and the bed of currants, ten inches thick

though dried, which underlay the pottery in chamber 11. In chamber 16

were large dome-shaped jar sealings with the name of Azab, and on one

of them the ink-written signs of the “king's ka" (pl.32, No.35).

The

entrance passage has been closed with rough brick walling at the top.

It is curiously turned askew, as if to avoid some obstacle, but the

chambers of the tomb of Den do not come near its direction. After nine

steps the straight passage is reached, and then a limestone portcullis

slab bars the way, let into grooves on either side; it was moreover

backed up by a buttress of brickwork in five steps behind it. All

this shows that the rest of the passage must have been roofed in so

deeply that entry from above was not the obvious course. The inner

passage descends by steps, each about five inches high, partly in the

slope, partly in the rise of the step. The side chambers open off this

stairway by side passages a little above the level of the stairs.

Plate 67: Section of the tomb of King Mersekha-Sempempses, and section and plan of the tomb of King Qa.

Some

detail yet remains of the wooden floor (p.16) planned on the lower part

of pl.67. There were two grooves or troughs across it, and two planks

running at right angles to the others. There seems no reason to assume

that the chamber was all one, without subdivision; probably these

grooves are the places for fittings or panels.

The roofing is

distinct in this tomb. Large holes for the beams remain in the walls,

with red burning round each, and in one a mud cast of the rough hewn

end of the beam. These beam holes are marked on the plan (pl.60), and

are not opposite to one another. This implies that there was an axial

beam, and that the side beams only went half across the chamber. A hole

in the floor still retained part of an upright post; this was not in

the true axis, but as much to one side as the post at the side of the

doorway. Probably therefore the axial beam ran rather to one side of

the chamber, as dotted on the plan. The greater depth of the beam holes

on the east side would imply that about an equal length of beam was

used on either side. As this is the only tomb with the awkward feature

of an axial doorway, it is interesting to note how the beam was placed

out of the axis to accommodate it. There is no evidence that the axial

beam was a ridge beam, on the contrary the holes seem to show that the

side beams were horizontal. Above the side beams is a plastered

wall with a moderate batter, probably to retain the coat of

sand over the roof, as in the tomb of Zet. The thin white lines

left in the brickwork of the plan show the place of finished faces in

the brickwork.

The interior of the chamber is 208.8 and

209 inches across between the floor beams, 410 and 412 in length

between beams. This was doubtless the size of the wooden chamber, as

the posts are set back 2.0 to 2.4 from the beam face, and that is about

the usual thickness of planks in these tombs. The height from the top

of the floor planks to the base of the beam holes, where is a row of

headers on edge, 101 1/2 inches; the foot of the plastered upper

wall is 115 1/2, and the top of that wall 162 inches. So the

chamber was intended to be 10 x 20 cubits, and 5 cubits high.

19. For convenience of reference the principal measurements of the tombs (in inches) are here placed together.

Tomb of Zet; see sect. 9:

Length inside extreme . N. 470.0 S. 481.5

Breadth inside extreme E. 369.5 W. 309.0

Length inside over beams mid. 360.2

Breadth inside over beams E. 241.7 W. 240.5

Chambers. Walls.

Along N. side, from W. 70.5 15.5

50.5 15.5

43.0 16.5

26.0 17.0

28.5 17.5

31.0 15.5

31.5 16.0

27.5 17.0

31.0

Along E. side, from N. 68. 16.5

56.5 16.5

59.5 17.

57. 16.

62.5

Along S. side, from E 39.5 17.

53.0 17.5

65.5 16.9

73.2 18.0

21.0 14.7

64.7 15.9

33.4 11.2

20.0

Height 89.6 to 95.3.

Deducting

2 x 6.8 from the dimensions over beams in order to find actual

dimensions in wooden chamber, we have 352.6 X 228.l or 226.9 for the

chamber; or 17 cubits of 20.74 and 11 cubits of 20.73 to 20.63.

(p.17) Tomb of Merneit; see sect.11:

Inner chamber, E. and W. 354; N. and S. 250.

Inner chamber high, 105.

Offering chambers, over all, W. 557; N. 454; S. 457.

Offering chambers, lengths, 160 to 215.

Cubit, 20,63 to 20.83; average, 20-75.

Tomb of Azab; see sect.14:

Length at base E. 258 W. 257.2

Breadth at base N. 165 S. 163.5

At top these dimensions are 7 1/2 to 20 larger.

Offering chamber:

Length at base N. 161 S. 161

Breadth at base E. 97 W. 98

At top these dimensions are 13 to 23 larger.

Stairway width 63 wide below to 76 above.

By tomb chamber cubit 20.44 to 20.64, mean 20-57.

Tomb of Mersekha; see sect. 16:

Length inside E. 656 W. 651

Breadth N. 291-4 S. 293-1

at 60 up 295-2 mid. 296-0

Along S. side E. 130-4 31-5 pil. 131-2 W.

Along E. side S. 523-0 107 door 26 N.

Wall. Chamber. Wall. Chamber. Wall

On

N. side 59

71 10 60

E.

“

67 50

16 64 16

S.

„

60 94

0 0 0

W

62 46

16 42 10

Greatest height 139, but incomplete.

Tomb of Qa; see sect. 18:

Length inside of beams E. 410, W. 412-5.

Breadth inside of beams N. 208-8, S. 208, mid. 209-2.

Depth from sand 110 under beams, 124 slope to 170.

Depth from floor lOl 1/2 under beams, 115^ slope to 161 ½.

Wall. Door. Wall. Door. Wall.

Along E. side passage 76 26 109 28 8

Cubit 20.5 to 20.88, mean 20.72.

Every

chamber was measured, and the details of positions of objects drawn at

the time of clearing; but it seems needless to state all the figures,

as they are plotted in the plans. The above dimensions are the only

ones from which any deductions are likely to be required. The mean

values of the cubit are 20.70, 20.75, 20.57, 20.72 inches. Probably

20.72 was the standard cubit of that age.

[Continue to chapter 3]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|