| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

The Royal Tombs of the First Dynasty (Abydos), Part I W.E. Flinders Petrie | | | | |

|

THE ROYAL TOMBS OF THE FIRST DYNASTY, PART I.

Chapter 3

THE OBJECTS DISCOVERED. (part 1; sections 20-22; plates 4-17)

20. The Stone Vases, pls.4.-10.

The

enormous mass of fragments of stone vases, mainly bowls and cups, found

in the tombs has not yet been fully worked over. Roughly speaking,

between 10,000 and 20,000 pieces of vases of the more valuable stones

were found; and a much larger quantity of slate and alabaster. The

latter it was impossible to deal with, beyond selecting such pieces as

showed the forms. In many cases a large group of fragments which were

found together was kept apart, and sorted in hopes of finding that they

would fit; but it was seldom that more than a very few could be joined.

The scattering of pieces has been so thorough during the various

plundering^ of the ground, that pieces of the same bowl are found on

the opposite sides of a tomb, or even in different tombs. To sort over

and reunite the fragments of individual bowls out of 50,000 or 100,000

pieces among stones with so little variety as slate and alabaster, and

after a great part had already been carried away by previous diggers,

was beyond the time and attention that our party could give. My

experience in dealing with the far more promising material of the

valuable stones shows how hopeless it would be to get results from the

others.

The less common stones were, however, thoroughly dealt

with. Every fragment was kept, the pieces from each tomb separately.

Those from one tomb were then sorted into about fifteen or twenty

classes of materials. Next all the pieces of one material were sorted

over, placing all brims together, all middle pieces with the axis

upright, and all bases together. Then every possible trial of fitting

was exhaustively gone through. In result a group of say 200 fragments

of one material, from one tomb, would be mainly united into perhaps 20

or 30 lots, each the pieces of one vessel, and lew ing less than half

over as irreducible residue. In this way, out of the tombs of Azab,

Mersekha, and Qa, I have put together parts of about 200 vases;

these are in most cases about a quarter to a half of the vase, enough

to draw the whole outline. These outlines remain yet to be copied. And

all the fragments from Zet, Merneit, and Den have yet to be sorted.

The

materials I avoid specifying at present, as many of them need careful

study to define them properly. The names of materials here used on the

plates are therefore intentionally vague. The frequent metamorphic

limestones and breccias are here only named "metamorphic"; the

saccharine marbles with grey and green bands are named “grey

marble": the frequent opaque white, with grey veins (geobertite

?) is named “white marble“; and "volcanic ash“ covers everything

between slate and breccia. To attempt precision before a full study of

the stones would only lead to errors.

21. The Inscriptions, pls.4—10.

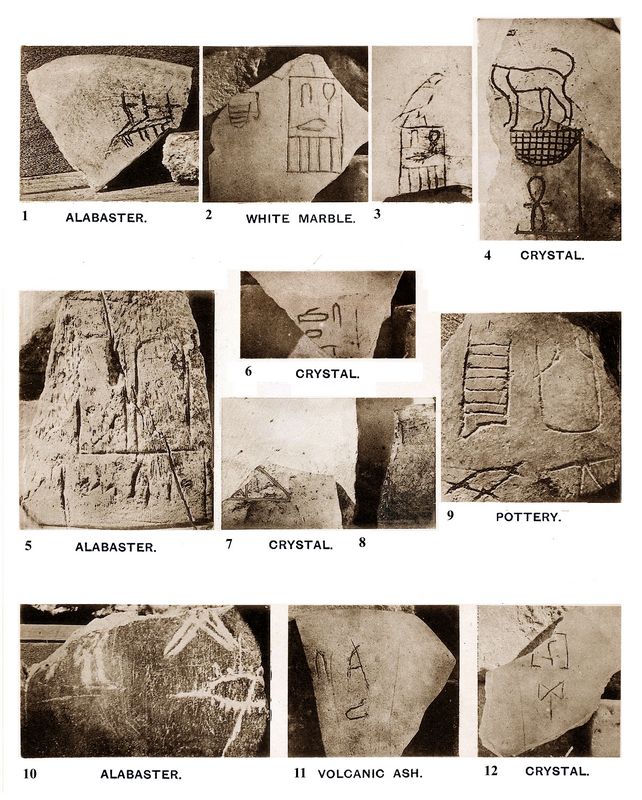

Plate 4: Inscriptions on stone vases from Kings Mena to Merneit.

We now turn to some individual notes.

Pl.4,1.

This piece of Aha was bought from the son of M. Amelineau's reis, who

had a great supply of fragments. We found a seal of Aha, and a shell

bracelet with apparently Aha on it, in the ground east of Zer, so no

doubt this piece came thence.

2. The piece of Narmer

is part of a great alabaster cylinder; in the rubbish of Den was found

a similar jar with a relief inscription (p.19) ground away, the traces

of which well agree to this name. The style of the hawk is the same as

on the work of Aha, and very different from that of any other king in

this Dynasty, pointing to Narmer hw ing reigned just before or after

Mena.

3. This is the only piece of Zeser, and being

found in an early tomb here it cannot be connected with Zeser the third

king of the III Dynasty. Rather is it like a piece of bowl of an

unknown king D, which I found lying at the Cairo Museum

(pl.32,32); both have the nebti without the vulture and uraeus,

apparently an earlier form. Even Aha-Mena used the animal figures over

the nebti; and these two names being superfluous to the 1st Dynasty,

suggests that they belong, with Narmer, to the Dynasty of ten kings who

are said to have reigned 350 years before Menes. Further excavation may

clear this matter. The fragment of ivory of Den appears in its proper

place in pl.11.

4. This finely cut group is unfortunately

imperfect; several more pieces of the bowl were found with it, but none

to complete the inscription.

5. This group is the same as

found scratched on pottery at the tomb of Zer, according to M.

Ainelineau, who reads it (Osiris, p.43) as ap khet (horns and

staircase).

6. This seems to be a name, Hotep-her,

apparently repeated as Her-hotep on a stele published by De Morgan, No.

808; see copy, pl.32.

7. This fragment was found

in the tomb of Merneit, and very unluckily has just lost the name. It

is deeply cut on a piece of a large crystal bowl.

8 seems to be a private name, Sunaukh.

9,10. Fragments of brown slate, the second with three jars.

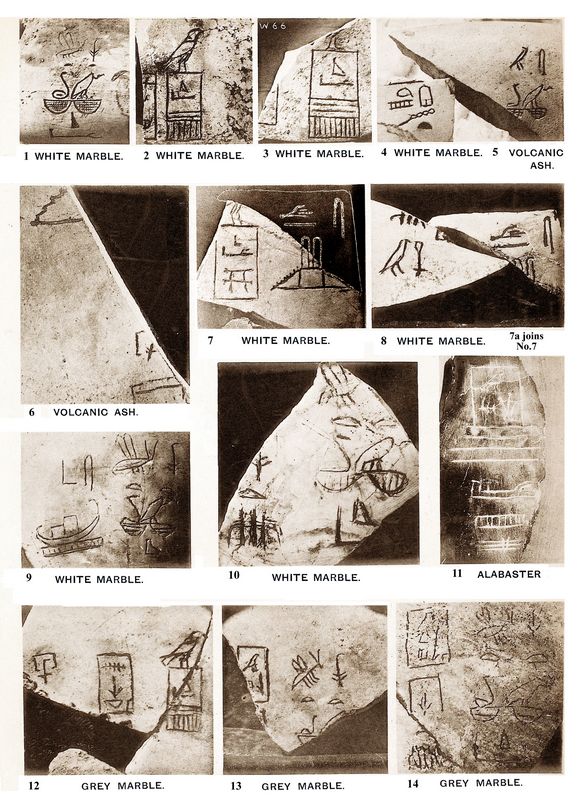

Plate 5: Inscriptions on stone vases of Kings Merneit and Den.

PL.5,1.

This piece of a thin delicate bowl is the only one with the full

drawing of the hieroglyph of Neit, as on the great stele (pl.1a); all

the other bowls have merely crossed arrows. Beyond on the left are

apparently the same signs as on No.3.

2,3,4,6,7. All these

are of burnt slate, of a bright brown. At first I supposed such slate

to have been accidentally burnt in the burning of the tomb; but a

bowl, found in a private grave, W 33, which had no trace of burning,

showed that this brown slate had been altered naturally by an eruption.

No. 2 has the per hez, or “white house," while 4 and 6 both name the

hat-s as the palace name, adding hez above it in 7. The khent sign in

No. 2, of vases set in a stand, should be noted. The 5 pieces were

found scattered in the tomb of Mersekha; they belong to an erased

inscription, and after finding the Merneit vases we can easily see the

crossed arrows of Neit on the left; on the right are traces of

rectangular signs. This is the only piece of Merneit identified as

being re-used; there may have been others now completely erased. But it

is noticeable that eight out of nine inscriptions of his are on slate.

No. 3 is kept at Cairo.

8, 9, are well-cut pieces of crystal

cups of Setui; the latter with an added inscription of Azab-Merpaba.

There is a fine style about all the carving of Setui, both in stone and

ivory, which is more dignified than that of any of the other kings.

10 is a fragment of slate found in the tomb of Setui; but the work looks rougher, and it may well belong to some earlier king.

11

is a beautiful piece of calcite with green patches. It was usurped by

Azab, and is the only piece of his that we found in his tomb.

12,

a fine piece of red limestone, has a boldly cut name of Setui, followed

by a rougher cutting of Merpaba. The latter shows that the signs which

have been read as neter below the hawks on the inscriptions of

Khasekhemui are the usual standards, as they also appear on pl.6,4, and

on the palette of Narmer. This piece is kept at Cairo.

Plate 6: Inscriptions on stone vases of King Azab-Merpaba.

PL.6,1.

(p.20) This slate bowl was found scattered on different sides of the

tomb, as were also the two pieces reunited in No. 3.

2 is a piece of a large alabaster cylinder jar, with coarse cutting.

5,6 are two fragments of a crystal cup with the name Merpaba, but one narrow slip between these pieces is lost.

8

is part of a very fine bowl in pink gneiss, the only example of such;

it was found with two other tine bowls in the grave W 33. The

inscription gives the name of the palace of Azab, Qed-hotep. One piece

of crystal cup of Azab, not figured here, was kept at Cairo.

9-11: Many

alabaster cylinder jars in the tomb of Mersekha had roughened places on

them, and at first it seemed as if they were merely unfinished; but

some traces of signs were found nearly erased, and this led to

searching them all carefully. Every piece of alabaster and slate that

was found was therefore closely looked at, usually in slanting

sunlight, to find erased inscriptions. Three are shown here: on 9

the traces of the door frame and of the heart sign are seen; on 10 is

part of a large hawk, and on 11 nearly the whole ka name is clearly

seen.

Plate 7: Inscriptions on stone vases of King Mersekha-Semempses.

Pl.7,1 is the only instance here of the three birds

group so usual on vases of Aha. The birds of Aha look most like

ostriches (see De Morgan, Nos. 558, 662), while these are more like

plovers; neither would be taken for the ba bird of later times,

and probably these are intended for rekhyt.

2, 3. Only two

names of Mersekha were found on vases, and most of the stonework in his

tomb seems to have belonged to Azab, as every piece on pl.vi. (except

No. 8) came from the tomb of Mersekha. The last sign on No. 3 scarcely

looks like kha, more resembling a fish; but the well-cut cylinder

impressions (pl.28, 73, 76, 77) leave no doubt that the sign is kha.

It is to be noted that the s sign always has the short side forward in

this name, on these two vases, and on all the seals on pl.28,

beside Nos. 17, 20, 34, and 41. This was not universal then, as the s

is the usual way of later times on seals, 5, 6, 7, 24, 25, 30, 32,

33, 40, 40, (i |., and 65; so it seems that there was no fixed rule as

in later ages.

4. This fine piece of crystal cup is united

from two widely scattered fragments. The lower part is a hat sign, as

the line on the left is too near the middle to be the side of the

square, and it must be the corner enclosure of the hat. So this reads

Neb hat ankh. There is also a scrap of a sign above the animal, which

seems to be probably a large hunting dog.

5

is a piece of

a large alabaster cylinder jar, with the festival sign on it, raised on

a platform which has steps at the end. This figure is best seen on pl.

8, 7, pl.11, 5, and pl.14,. 12. On the basis are three signs (?)

SN. On

No. 7 is N, and on No. 8 is SN .... All of these refer to the Sed

festival.

6 is a palimpsest crystal bowl; of the earlier

inscription traces remain in spite of the scraping and re-polishing of

it, and the sign su was brought up clearly by careful wiping over with

ink. The later inscription is Sed heb, the “Sed festival."

9

is a piece of black pottery placed here on account of its inscription.

The signs ka, a door (?), and mer, are clear. The unknown sign is like

one in an ink-written inscription on slate from Abydos, now at Cairo

(pl.32,38).

10 is on a coarse piece of an alabaster

cylinder jar; it is the name of Azab's city or palace, Hor-dua-kh, as

on the seal pl.26, 03.

11, 12 are two inscriptions which

cannot be explained yet. The double-headed axe, after the “royal house“

on 12, also appears in the hands of the warriors on a slate palette.

Plate 8: Inscriptions on stone vases of King Qa.

Pl.8,1

is on a piece of a large white bowl, and is better cut than any of the

others of this reign. It is now in the Cairo Museum.

5 shows that it belonged to the priest of the shrine of Qa, like the bowl in pl.19, 12.

6,7,

both refer to the Sed festival; the upper (p.21) part of 7 was not

fitted on before photographing, but is given separately as 7a, and is

outlined in place above 7.

9 has a boat on it somewhat like the prehistoric boats, high at both ends, and having

two cabins.

11,12,13,14, and pl.9, 1,2,3, all refer to the two buildings named Sa-ha-neb and Hor-pa-ua.

Plate 9: Inscriptions on stone vases of King Qa.

No.1,

pl.9, clears up the difference between these; at the right are

parts of an inscription like that on No.3, showing that the building

Hor-pa-ua was first inscribed along with the king's name; and then

later the building Sa-neb-ha was inscribed on the bowl. Thus the "house

of the sole Horus" — Hor-pa-ua — was the name of the palace; and the

“house of all fortune" — Sa-ha-neb — was the name of the tomb, where

the bowl was later deposited. A variant is seen on the piece of a great

alabaster cylinder jar “Hor-ha-sa." The details of these inscriptions

are considered by Mr. Griffith in his account.

Pl.10,

1 to 7. These are some of the pieces of stone bowls inscribed with ink.

1 and 2 are very illegible, owing to being faintly marked on dark

slate; but on 1 is the name of Setui, though found in the tomb of

Mersekha. These will be drawn and published on their reaching England.

4 has the name of the crocodile hems.

22. Ivory Tablets, pls.10 to 17.

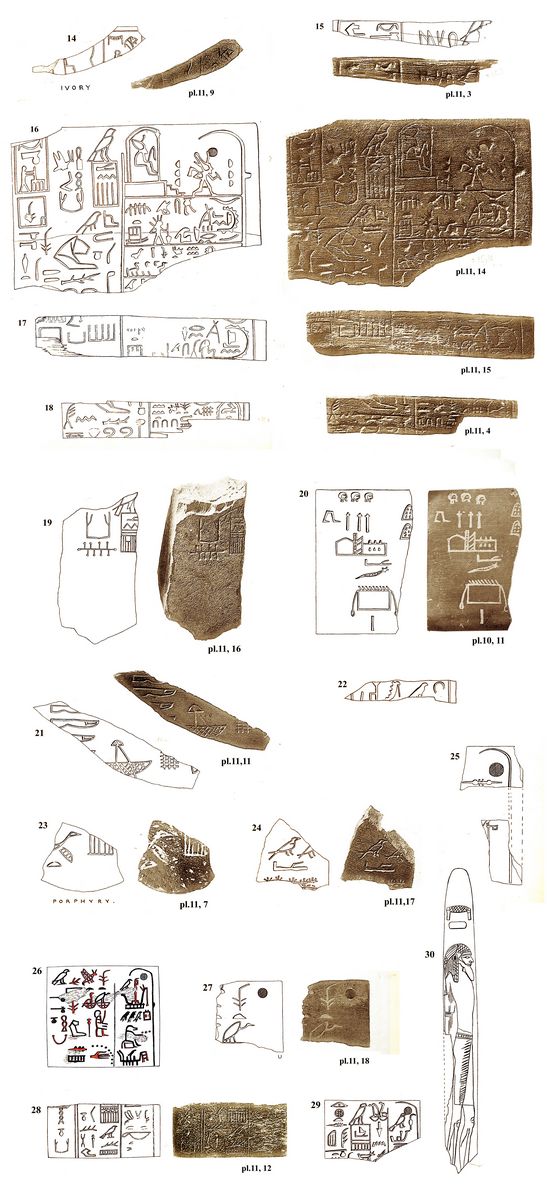

Plates 13 (Nos.1-6) and 14 (Nos. 7-12) : Ivory tablets of Kings Zet and Den- Setui. Photographs of tablets from plates 10 and 11 are added.

We

shall here follow the order of the drawings (pls.13 to 17), as the

photographs (pls.10 to 12) are somewhat out of order owing to only part

of the objects having been photographed in Egypt and the remainder in

England.

Pl.13, 1 This slip of blackened ivory, and the triangular piece pl.11, 2, were

both from the inlaying of a box or furniture. For a photograph see pl.10, 8 which is now kept at

Cairo.

Pl.13,

2 is the end of

a small casket, with grooves and holes on the back for joining it

to the sides (see photograph in table 10. 9). Unfortunately it was

broken in finding, and [in the horus sign, the hawk seated on

a rectangular palace] the serpent was lost; but the tail of the serpent

is still visible, and it was found in the tomb of Zet, so there

can be no doubt of its source. The last sign is like the prehistoric

amulet often found. (Naqada, lviii. Q 709.5; Lxi., 4.)

Pl.13, 3, part of an ivory tablet of Zet (see pl.11,1) found in his tomb.

Pl.13, 4 a fragment of ivory, for inlaying like 1; from tomb of Zet.

Pl.13, 5

is part of an ivory tablet (pl.10,10) from a private grave Z 3. The

figure of a man pounding enters into the name of the palace of Setui

(pl.15,16).

Pl.13, 6 is part of an ivory boat, apparently. The

position is shown by the flat base; the surface of the sides is mostly

flaked away, so that the form is uncertain. On the top is a flight of

steps leading up. The name of Zet is on the side, and it was found in

his tomb.

Pl.14, 7 and 7a, a piece of an ivory tablet, gives

a portrait of Den-Setui (see also pl.10, 13). It shows the double crown

fully developed, and the traces of colour are red for the Lower crown,

white for the Upper, as later on. This piece is kept in Cairo. The ankh

on the reverse has the divided tails as on the vase at pl.7, 4.

Pl.14, 8

is a fragment (see pl.11, 8) with Den in the attitude shown on the

sealing drawn in pl.32, 39. A part of a sign on the reverse is placed

beside it.

Pl.14, 9 shows Setui standing with staff and mace, preceded by standards (see also pl.10, 14).

Pl.14, 10 is a fragment of ivory (see photograph, pl.11,10) with numerals “1200," as on the ebony tablets pl.15, 16,18.

Pl.14, 11 is a piece of a thick tablet with apparently the same numerals (see pl.11,6).

Pl.14, 12

is a piece of ivory, with signs also on the back, pl.14, 12a (see pl.11,5).

This is one more mention of the Sed festival, so often found on the

stone vase inscriptions. These festivals have been discussed, as to

whether they were every 30 years of a reign, or at fixed intervals of

30 years. The latter is the only use which (p.22) would agree with

their undoubtedly astronomical origin, by the shift of the moveable

calendar one week every 30 years, and one month every 120 years at the

Great Sed festival. I have also already shown (History, ii. 32) how

these festivals do not fall on the 30th year of the reigns, and often

were in reigns of less than 30 years. Now we have this again

illustrated. Those festivals are named on the tablet of Setui

(pl.14,12), on vases of Mersekha (pl.7, 5,6,7,8), and on vases of Qa

(pl.8, 6,7), but never by Azab.

Now in Manetho the

reigns of these kings are 20, 18, and 26 years, not one reaching 30

years. Moreover, we can test whether a series of 30- year intervals

will fall in these reigns. Taking approximately the dates given in my

History, I. 27*, we have:

BC

30-year intervals.

4604

Hesepti = Setui 4588-4

4584

Merpaba

.

4558

Semenptah.

4558-4

4540

Kebh

= Qa

4528-4

4514

So

there is only a range of 4 years left possible for the 30-year cycle to

fall upon within these reigns; and if Merpaba had a Sed festival, it

would have upset the series. As it is—crediting Manetho's reigns—we

have the Sed cycle fixed to within 4 years in the 1st Dynasty. We see

then that all the evidence from these inscriptions is in fw our of a

fixed cycle of 30 years, quite independent of the kings' reigns. This

cycle implies the loss of the day in leap years, which causes the shift

of the calendar; and hence implies the calendar of 365 days being in

use as early as the middle of the 1st Dynasty, and the known loss of a

day in four years.

Plates 15 (Nos.14-18 ), 16 (Nos.19-25) and 17 (Nos. 26-30) : Ebony and ivory tablets of Kings Den-Setui, Mersetha, and Ka. Photographs of tablets from plates 10 and 11 are added.

Pl.15, 14 is a piece of a finely cut

ivory tablet (see photograph in pl.11, 9), which shows part of the palace name, nub

hat and the man pounding, as in No.16.

Pl.15, 15 is a chip of an ebony tablet, with part of the palace name, and the hawk and sahu biti (see pl.11, 3).

Pl.15, 16

is the most important tablet, though the lower edge has not been found

(see photograph in pl.11,14). The scene of the king dancing before Osiris seated in

his shrine is the earliest example of a ceremony which is shown on the

monuments down to Roman times; he bears the hap and a short stick

instead of the oar; the three semicircles on each side are, even

at this early stage, unintelligible. The inscriptions below, referring

to the festival, will be dealt with by Mr. Griffith; but we should note

that the royal name Setui occurs in the lower register, so this tablet

is good evidence for that king being Den, besides the clay sealings not

yet published.

Beyond there is the name of Den, and that of

the royal seal-bearer Hemaka, which occurs so often on the jar

sealings. The palace name is written with nub, apparently a hatchet,

and the man pounding, for which see Nos. 5 and 14. The two signs after

suten look like different forms of hatchet, see also Nos. 15, 26, 29.

For the numerals “1200“ at the bottom edge compare also Nos. 10, 11,

18. This tablet was crusted with melted resin, harder than the wood;

and the only way to clean it was by powdering the resin with a needle,

while watching it with a magnifier: so it is possible that some point

may not have been fully cleaned out.

Pl.15, 17 is a piece of

another ebony tablet, a duplicate of the previous one (see pl.11, 15);

but it is useful as showing a different grouping of the signs, which

helps the explanation of them.

Pl.15, 18 is another ebony piece,

somewhat like the previous pieces (see pl.11, 4); but it shows a

place name beginning Unt . . . , and also the royal name of King Setui.

Pl.16, 19. A piece of a very thick ivory tablet, much burnt: see pl.11, 16.

Pl.16, 20.

Part of a well-cut ivory tablet (p.23), finely polished, blackened with

burning: see pl.10, 11. The inscription seems to refer to the great

chiefs coming to the tomb of Setui; and the figure of the tomb is the

oldest architectural drawing known. It appears to show the tomb chamber

at the left, with a slight mound over it. The tall upright may perhaps

show the steles at the tomb, standing up like the poles in front of the

shrine at Medum (Medum, ix.); see also poles at the side of a shrine of

Tahutmes II. (L.D.), in.15). Next is apparently a slope descending to

the tomb, the stairway of the tomb; while at the right is a diagram of

the cemetery of graves in rows around the tomb, with the small steles

standing up over the graves. The square enclosure of the graves, as in

pl.lxi., each with a small stele over it, must have been a marked

feature in the appearance of this cemetery.

Pl.16, 21-24. Fragments photographed: 21 in pl.11, 11; 23 in pl.11, 7; 24 in pl.11, 17.

Pl.16, 25. Two pieces of apparently the same tablet, judging by thickness, work, and colour.

Another piece of Setui is shown in pl.10, 12, but not drawn. It is the edge of a thick piece from some furniture.

Pl.17, 26.

This ivory tablet of Mersekha was found in the doorway of his

tomb: see pl.12,1. It is deeply cut, and coloured with red and

black as shown in the drawing. The formula is much like that on the

Palermo Stone, and without going into the interpretation of it we may

note the remarkable reading of Horus as Heru, written with three hawks,

like Khnumu written with three rams (Season in Egypt, xii., 312); the

figure of Tahuti seated accords with the early worship of the baboon,

for which see the diorite baboons in the granite Temple of Khafra. The

figure which is placed for the king's name is like that on the sealing

(pl.28,72), but differs from the figure of Ptah in the Table of Abydos.

This figure can hardly be intended for Ptah: and it seems as if it

might be a shemsu, and so give the Greek form Semempses, or else a sam

priest of Ptah. The group of suten and two axes occurs also on the

Setui tablet, pl.11, 14. And the name Henuka is seen on the tablet

No.28.

Pl.17, 27. This fragment of royal titles was found in the tomb of Mersekha: see pl.11, 18.

Pl.17, 28.

This half tablet of ivory was found by the offering place of Qa, on the

east of the tomb. The ka name appears to end with the arm, and hence it

might be supposed to be of Qa; but the signs after the suten biti

cannot be so read, and look much more like ket, with the small bird

determinative: see pl.11, 12.

Pl.17, 29. Part of a thin ivory

tablet, see pl.12,2: found on the east of the tomb of Qa. It seems to

give an unknown royal name Sen . . . below the vulture and uraeus. As

Qa succeeded Mersekha, we should expect to find the name of Kebh. It

seems possible that a sen sign with very tall base (as on a stele,

pl.34, 13) was mistaken by a later scribe for the vase kebh, and the n

below for a determinative of water. After seeing Setui made into

Hesepti, Merpaba into Merbap, and the figure on pl.17, 26 turned into a

statue of Ptah, we can well believe in a possible confusion of the

early form of sen and kebh.

Pl.17, 30. This ivory carving is the

most important artistic piece that was found. It is carved on the back

with the knots and bracts of a reed, and imitates one of the strips of

reed used for casting lots or gaming. In the present time Egyptians

throw half a dozen slips of reed on the ground, and count how many fall

with outside upward, to give a number as with dice. The inner side of

this slip, which was probably one of a set, is carved with a bound

captive. The work is excellent, as may be seen in the photographs

pl.12, 12,13. The plaited lock hanging down, the form of the beard, and

the face, all agree to this being a western man or Libyan. But the long

waist-cloth seems hardly to be expected at a time when, as the slates

and ivory carvings of Hierakonpolis show (p.24) clothing was not

much developed. This is good evidence for the usual waist-cloth of the

Old Kingdom being Libyan in origin.

[Continue to chapter 3, part 2]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|