| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

The Royal Tombs of the First Dynasty (Abydos), Part I W.E. Flinders Petrie | | | | |

|

THE ROYAL TOMBS OF THE FIRST DYNASTY, PART I.

(Report published in 1900 by the Egypt Exploration Fund).

Chapter I

INTRODUCTION.

1. Details of publication. 1

2. Previous wreck of tombs. 1

CHAPTER I. The Site of the Royal Tombs

3. The views of the site. 3

4. The group of tombs. 4

5. The order of the tombs 5

6. Appearance of the tombs 6

7. Later history of the tombs 6

Fig.1: Map of Egyptian sites, showing location of Abydos.

KINGS MENTIONED IN THIS VOLUME.

Inscriptions.

ZESER

Order unknown;

NARMER

probably before Mena

1st Dyn.

Manetho[1] Sety List. Tombs.

1.

Menes

Mena = AHA —

MEN

Probable order

2. Athothis Teta =

ZER

Probable order

3. Kenkenes Ateth =

ZET

Probable order

4. Uenefes Ata =

MERNEIT

Probable order

5.

Usafais

Hesepti = EN —SETUI

Order

certain.

6.

Miebis Merbap

= AZAB — MERPABA Order certain.

7. Semempses Semenptah= MERSEKHA - SAMENPTAH Order certain.

8.

Bieneklies

Kebh = QA — SEN (p.

23) Order certain.

2nd

Dyn.

PERABSEN

KHASEKHEMUI

THE ROYAL TOMBS OF THE 1st DYNASTY

INTRODUCTION

1.

The work described in this volume is but a portion of that carried out

during the past winter, 1899-1900. In most places it is essential to

finish the work in one season, and therefore to include everything in

one volume. But as Abydos is a subject for several years' work, there

is no need to delay the issue of the most important results while the

lesser but more tedious matters are being prepared. Hence this volume

does not profess to be complete, but is only some advance sheets of a

longer publication which will be completed next year. Large quantities

of the more bulky materials, such as jar searings and pottery, have

been left undrawn, to await issue in future; and the whole of the

results of the periods of the XVIII Dynasty and onward will appear in a

later volume. The present plates are but a portion of the material from

the 1st Dynasty, with a brief account of the subjects, but so important

a portion that we do not wish to keep it back for a year or two, or

even a month. This has led to reversing the order, and issuing it

before last year's results from Diospolis Parva, but the relative

importance of the two is sufficient reason for this course.

The

materials here published were prepared in Egypt during the excavating

season, and some two hundred photographs and the drawings for over

forty plates were brought home ready to use. My wife dreAv the tomb

plans and all the marks on pottery, and I have to thank Miss Orme for

inking the drawings of jar sealings. Thus I have been able to put

everything in the printers' hands within eighteen weeks from the

beginning of the excavations. I need not refer to our party at Abydos

in detail, as, excepting a little occasional help, the work on the

royal tombs, and the photographing and drawing, was my own share of the

season's work. Mr. MacIver worked on the prehistoric age and a temple

of the XII Dynasty; Mr. Mace on the cemetery of the XVIII to XXV

Dynasty; I worked some cemetery of the prehistoric and of the XXX

Dynasty; and for the Egyptian Research Account Mr. Garstang worked a

cemetery of the XII and XVIII Dynasties. All this material, of much

interest historically, will be published after it has been properly

worked up. Some of the photographs need apology; my plates were soon

exhausted by the great number of objects, a further batch from England

did not arrive, and I had to fall back on very unsatisfactory plates,

which were the best to be got in Cairo. Messrs. Waterlow's phototypes

are better than I could have expected from such negatives.

2.

It might have seemed a fruitless and (p.2) thankless task to work at

Abydos after it had been ransacked by Mariette, and been for the last

four years in the hands of the Mission Amelineau. It might seem a

superfluous and invidious labour to follow such prolonged work. My only

reason was that the extreme importance of results from there led to a

wish to ascertain everything possible about the early royal tombs after

they were done with by others, and to search for even fragments of the

pottery. To work at Abydos had been my aim for years past; but it was

only after it was abandoned by the Mission Amelineau that at last, on

my fourth application for it, I was permitted to rescue for historical

study the results that are here shown.

Nothing is more

disheartening than being obliged to gather results out of the fraction

left behind by past plunderers. In these royal tombs there had been not

only the plundering of the precious metals and the larger valuables by

the wreckers of early ages; there was after that the systematic

destruction of monuments by the vile fanaticism of the Copts, which

crushed everything beautiful and everything noble that mere greed had

spared; and worst of all, for history, came the active search in the

last four years for everything that could have a value in the eyes of

purchasers, or be sold for profit regardless of its source; a search in

which whatever was not removed was deliberately and avowedly destroyed

in order to enhance the intended profits of European speculators; a

search after which M. Amelineau wrote of this necropolis: "tous les

fellahs savent quelle est epuisee." The results in this present volume

are therefore only the remains which have escaped the lust of gold, the

fury of fanaticism, and the greed of speculators, in this ransacked

spot. These sixty-eight plates are my justification for a fourth

clearance of the royal tombs of Abydos.

PUBLICATIONS REFERRING TO THE ROYAL TOMBS.

J. de Morgan. Recherches sur les Origines de I'Egypte, ii., 1897. (Account by G. Jequier.)

E. Amelineau. Lcs nouvelles Fouilles d'Abydos. Compte rendu, 1895-6.

1896-7.1897-8.

E. Amelineau. Lcs nouvelles Fouilles d'Abydos, in extenso, 1896-7.

E. Amelineau. Le Tombeau d'Osiris (monographic), 1899.

G. Maspero. Reviews in Revue Critique (Jan. 4, 1897; Dec. 15, 1897).

K. Sethe. Aeltcstcn geschichtichcn Denkmaeler, in Zeitschrift f. A. S., xxxv. 1.

W. Spiegelberg. Ein neues Denkmal, in Zeitschrift f. A. S., xxxv. 7.

A. Erman. Bemerkung, in Zeitschrift f. A. S., xxxv, 11.

CHAPTER I.

THE SITE OF THE ROYAL TOMBS.

3.

Abydos is by its situation one of the remarkable sites of Egypt. At few

places docs the cultivation come so near to the edge of the mountain

plateau; the great headland of Assiut, the cliffs of Thebes, or the

crags of Assuan, rival it, but elsewhere there lie generally several

miles of low desert between the green and the mountain. At Abydos the

cliffs, about 800 feet high, come forward and form a bay about four

miles across, which is nowhere more than a couple of miles deep from

the cultivation (see pl.3.). Along the edge of this bay stand the

temples and the cemeteries of Abydos; while back in the circle of the

hills lies the great cemetery of the founders of Egyptian history, the

kings of the 1st Dynasty.

The site selected for the royal

tombs was on a low spur from the hills, slightly raised above the

plain, and with a deep drainage ravine on the west of it, so that it

never could be flooded. Strictly speaking, the river valley, the hill

line, and the tomb orientation, are all diagonal to the compass, the

sides of the tombs being N.E., S.E., S.W., and N.W. But for facility of

description it is assumed here that the river runs north and south, as

it usually does in Egypt, and that the tombs lie correspondingly. That

the ancient Egyptians recognized the diagonal direction is seen by the

corner of the wood-paving of Mersekha being marked "north." In all

those descriptions “north" means more exactly 44° W. of N. magnetic.

Plate 1:

1 (top). View from Kom es sultan. Royal cemetery in far distance.

2 (bottom). View from Fort (Shumeh). Royal cemetery in distance.

Advancing

up to the old fort our next view (pl,1, fig.2) is taken at the side of the

little signal heap seen on the further corner of the fort in view 1;

marked phi 2 in the plan.

From that we still have a stretch of the historic cemetery before us.

But the distant royal cemetery is clearer, below the mouth of the

valley; and the mounds are seen to be one long uniform mass, with a

short ridge nearer and a little to the left. The long mass covers the

royal cemetery; and the heap to the left is the rise marked as Heqreshu

on the plan (pl.3). This rise is so called as the ushabtis of a

noble of the XVIII Dynasty, named Heqreshu, were found here. This

ground was a favourite place for high people of that age to have their

ushabtis buried in, so as to be near Osiris, and ready to work in his

kingdom. No human burials were found; but ushabtis of some half dozen

persons were found here, and about the same number were found by the

Mission Amelineau.

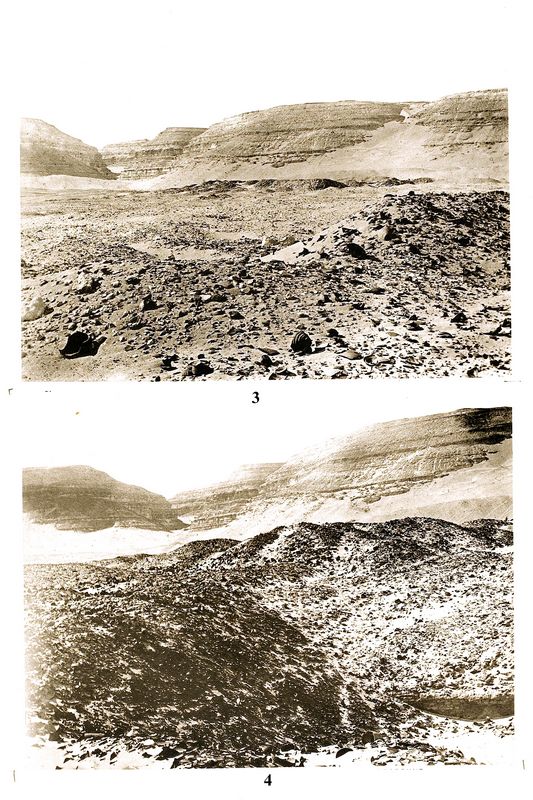

We next, in the view (pl.2, fig.3), have gone forward to this hillock of Heqreshu, to the point phi

3 in the plan. The foreground is strewn with broken pottery, of

offerings made there in the XVIIIth Dynasty and onward. The mounds over

the royal tombs now separate into the (p.4) heaps of Mersekha on the

left, the great banks of pottery of the Osiris shrine in the middle,

and the heaps over Perabsen on the right.

The situation is wild and silent; close

round it the hills rise high on two sides, a ravine running up into the

plateau from the corner where the lines meet. Far away, and below us,

stretches the long green valley of the Nile, beyond which for dozens of

miles the eastern cliffs recede far into the dim distance.

Plate 2: 1: Royal cemetery from Hegreshu Hill. 2: Royal cemetery. Wall of Tomb of Zer in foreground.

4.

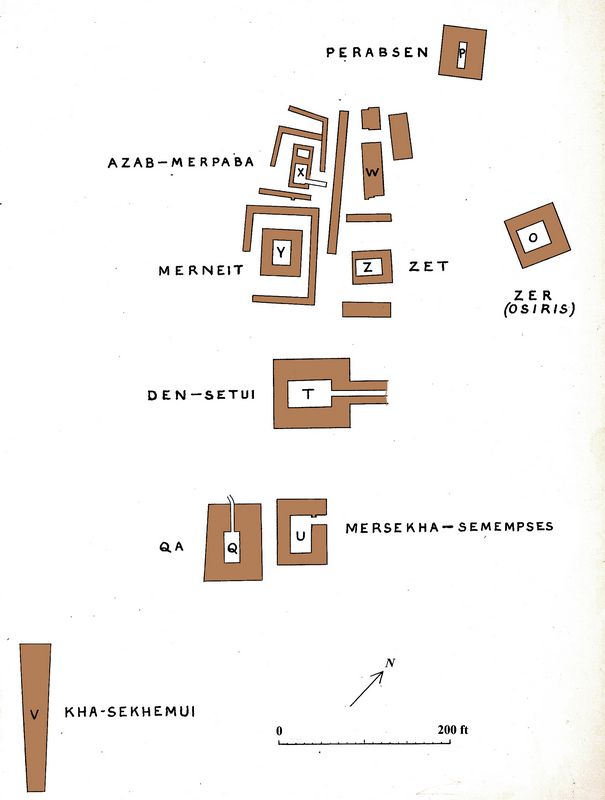

Looking at the group of tombs, as shown on pl.3, 3b, and pl.59., it is

seen that they lie closely together. Each royal tomb is a large square

pit, lined with brickwork. Close around it, on its own level, or higher

up, are small chambers in rows, in which were buried the domestics of

the king. Each reign adopted some variety in the mode of burial, but

they all follow the type of the prehistoric burials, more or less

developed. The plain square pit, like those in which the predynastic

people were buried, is here the essential of the tomb. It is surrounded

in the earlier examples of Zer or Zet by small chambers opening from

it. By Merneit these chambers were built separately around it. By Den

an entrance passage was added, and by Qa the entrance was turned to

the north. At this stage we are left within reach of the early

passage-mastabas and pyramids. Substituting a stone lining and roof for

bricks and wood, and placing the small tombs of domestics further away,

we reach the type of the mastaba-pyramid of Seneferu, and so lead on to

the pyramid series of the Old Kingdom.

Plate 3:

Sketch map of the plain at Abydos, showing main

structures, location of royal cemetery, and places of the

photographs in plates 1 and 2.

The plan at pl.59 is

left intentionally in outline as the survey is not completed, and until

we have accurate plans of the tombs that I have not yet opened, it is

impossible to finish it uniformly. It might be supposed that the plans

already published wvould suffice, and that I might incorporate those.

But the uncertainties which surround them are so great that it is

impossible to rely on them. M. Jequier, in the Recherches sur les Origines de Egypte,

ii, on p. 232 has given a plan called the “tombeau du roi Ka," but the

form is that of the central chamber of Mersekha, and the scale shows it

to be 328 inches long, while that of Qa is 428, and that of Mersekha

523 inches; its proportion of length to breadth is as 1: 2.28, that of

Qa is 1: 1.90, and that of Mersekha 1: 1.80; it has no entrance, and

both Qa and Mersekha have wide doorways. Thus neither in size,

proportion, nor detail can it be followed.

Plate 59: Outlines of the Royal Tombs at Abydos.

The next plan, that of the “tombeau du roi Ti" (p. 242)

— or as he should be called, Khasekhemui—is by scale 2068 inches long,

by measure of the breadth 2810 long, and is stated in the text to be 83

metres or 3260 inches long: probably the text is corrupt and should

read 53. The details of the tomb I cannot verify until it is cleared.

Turning now to M. Amelineau's plans ("Nouvelles Fouilles, 1897-8"), the

"tombeau d'Osiris," that is (p.5) of King Zer,[2] is shown (p.

39) with the shortest dimension N. to S., in the text the shortest is

E. to W.; the detail I have not yet verified. In the plan of the tomb

of Perabsen, north and south are interchanged, and the scale is about

1:170 or 180, instead of 1: 200 stated; the contraction to the N. end

is unnoticed, but details I have not yet verified. It will thus be seen

that there was room for some fresh plans to be made of these tombs.

5.

The sequence of the tombs is to be carefully studied. As will be seen

on pls.11, No.14, and 15, No.16, the king whose ka name is Den is also known as

the suten biti setui, a name which Dr. Sethe has correctly suggested to

be that misfigured in the table of Abydos as Hesepti, the fifth of the

Dynasty. Further, by the sealings shown on pl.26, No. -57, the king

with Jca name Azab is also known as Merpab, doubtless King Merbap, the

sixth Dynasty. Further, by the sealing of the on pl.28, No. 72,

the king with the Jca name Mersekha is the seventh of the Dynasty,

figured in the Abydos table much like a statue of Ptah, and called

Semempses by Manetho. That this is to be read Sem-en-ptah is very

doubtful in view of the original form of the figure, which is best

seen on the tablet pl.17, No. 26; it seems more likely to be a

follower, shemsu, or possibly a "priest of Ptah." Beside the absolute

identification of three of the kings with those in the list of Abydos,

we can add several proofs of relative order from the inscriptions on

vases found appropriated by later kings. In this way a vase of Narmer

(pl.4, No. 2) is found in the tomb of Zet, and another erased in the

tomb of Den. A vase of Den-Setui (pl.5, No. 11) is found re-engraved

by Azab. Many vases of Azab arc found erased and re-used by Mersekha,

pl.6, Nos 9-11.

Therefore we may, from the evidence of the tomb inscriptions alone, restore the order of the kings as:—

Narmer

Zet

Den = Sctui

Azab = Merpaba

Mersekha = Semempses.

Hence the order of Manetho is confirmed for the three kings who are identified.

We

may now turn to the plan, as we can be certain that the order of

building is Den, Azab, Mersekha. It needs little notice to see that Qa

naturally follows this group. Of the earlier tombs it seems probable

that Merneit is before Den, Zet earlier still, and Zer (or Khent)

before these; the gradual pushing back of the tomb sites being pretty

clear. We therefore must look on the most eastern tombs as the

earliest, and this is confirmed by private tombs to the east of Zer,

which contain a jar sealing and a shell bracelet of King Aha. That Aha

must come very early in the 1st Dynasty is already clear; the style of

his work is certainly ruder than anything else in the Dynasty, and the

form of the hawk on his vases is closely like that of Narmer, who comes

before Zet and Den. Thus Aha must, from evidence of style, and position

of his objects, come within a reign of Mena; and there is no reason

for not accepting the identification of him with Mena; especially now

that it is shown to be usual for the king's name to be simply written

below the vulture and uraeus group.

Thus we are led to the following order of kings:—

By

tombs.

Table of Abydos. Manetho.

Aha

Mena

Menes

Zer

Teta

Athothis.

Zet

Atet

Kenkenes

Merneit

Ata

Uenenfes .

Den—Setui

Hesepti

Usafais

Azab—Merpaba

Merbap

Miebis

Mersekha

...ptah

?

Semempses

Qa—Sen

Qebh

Bienekhes

(p.6)

and we have left yet unplaced King Narmer, who must be before Zet; King

Zeser (pl.4, No.3), and King D (pl.32, No. 32); these two last

seem connected by the title being only two neb signs, without the

vulture and uraeus. Zeser is before Den, as the piece was found re-used

in Den's tomb. King D I found on a piece of vase in the Cairo Museum,

where it had lain unobserved. If Narmer came after Mena there would be

a difficulty, as there would be four names between Aha and Den, and

only three between Mena and Hesepti; but there is no proof but what

Narmer may be before Mena, as Zeser and D may be. The position of a

king who seems to be named Ket (pl 11, No.12; pl.17, No. 28)

is also uncertain; the piece was found by the offering-place of Qa.

6. We may now

notice the appearance and history of the royal cemetery in later times.

The tombs as they were left by the kings seem to have been but slightly

heaped up. The roofs of the great tombs were about six or eight feet

below the surface, an amount of sand which would be easily carried by

the massive beams that were used. The lesser tombs had about five feet

of sand over them. But there does not seem to have been any piling up

of a mound; not only is there no such excess of material remaining, but

the condition of the steles, as we shall next describe, shows that the

level of the soil remained uniform for a long time, whereas a mound

would have been continually degrading and accumulating blown sand.

Plate 00 (frontispiece): Stele of King Merneit at Abydos.

On

the flat, or almost flat, ground of the cemetery the graves were marked

by stone steles set upright in the open air. The great stele of Merneit

(plate 00) shows clearly the level to which it was buried; below

that point the stone is quite fresh, above that the exfoliations are

due to moisture soaked up from the earth, and the upper part is

sand-worn. Other small steles show very plainly the lower part

absolutely fresh and unaltered, and the upper part deeply sand-worn;

the division between the two being within a, quarter of an inch.

Each

royal grave seems to have had two great steles. I found two of Merneit,

one almost perished; there were two of Qa, one found by the Mission

Amelineau, one by myself; and though only one has been found of Zet and

Mersekha, yet one such might well be lost, as none have survived of

Zer, Den, or Azab. The steles seem to have been placed on the east side

of the tombs, and on the ground level. Those of Merneit had fallen into

the tomb on the east side, the fragments of steles of Mersekha lay on

the cast side, the stele of Qa lay on the ground level at the east

side, and close by it were many stone bowls, one inscribed for "the

priest of the temple of Qa."

Hence we must figure to ourselves

two great steles standing up, side by side, on the east of the tomb:

and this is exactly in accord with the next period that we know, in

which, at Medum, Seneferu had two great steles and an altar between

them on the east of his tomb; and Rahotep had two great steles, one on

either side of the offering-niche east of his tomb. Probably the pair

of obelisks of the tomb of Antef V at Thebes were a later form of this

system. Around the royal tomb stood the little private steles of the

domestics (pls.31 - 36) placed in rows, thus forming an enclosure

about the king.

7. The royal cemetery seems to have gradually

fallen into decay; the steles were blown over or upset wantonly, and

the whole site was neglected and forgotten in the later ages. There are

no offering vases there of the pyramid age, nor of the Middle Kingdom.

But the revived grandeurs of the XVIII Dynasty awakened (p.7) some

interest in the tracing of the history. Tahutmes III had a roll of

ancestors compiled, which though very erratic, yet showed an interest

in the past; and Sety I succeeded in having a fairly correct list made,

in which a few blunders occurred in the early names, as we see by the

differences between the inscriptions of the 1st Dynasty and the Table

of Abydos, but which seems to have been historically in order.

This

revived the interest in the cemetery which tradition had known as that

of the early kings. Offerings began to be made to the kings at their

tombs; but very blindly, as several places which did not contain any

royal tomb were heaped up with potsherds, while some of the royal tombs

(as Merneit and Azab) had scarcely anything placed on them. Tn this

uncertainty the rise marked "Heqreshu," pl.3 was evidently

supposed to be important, though there was nothing older there than a V

or VI Dynasty tomb of an official named Emzaza.

A great impetus

to offerings was given by the adoption of one of the royal tombs, that

of king Zer, as a cenotaph of Osiris. The granite bier of Osiris placed

in it was probably of the XXVI or a later Dynasty; but in the XVIII

Dynasty the site had been adopted as the focus of Osiris worship, the

earliest of the pottery heaped over it being the blue painted jars

which came in under Amenhotep II or III. The later offerings were

mainly of the XXII to XXV Dynasty, during which an enormous pile of

broken jars accumulated over the tomb.

In the XXVI Dynasty a

chapel was built here by Haabra, of which part of a door-jamb was found

thrown into the tomb of Merneit (pl.38); scattered like the

fragments of the bier of Osiris, which we found, one by Azab and the

other a furlong away on the south. Further building was done here by

the Prince Pefzaauneit under Aahmes; but the interest in the site faded

under the Persians, and beyond a few stray scraps of Roman pottery and

glass there is nothing later found here.

At what time the

burning of the woodwork took place is not fixed. It was certainly long

after the original burial, as the wooden floors mostly remain quite

uncharred, and the walls seldom show anv burning toward the bottom. The

only tombs with burnt floor arc that of Merneit and part of Mersekha.

In the tomb of Azab it is clear that the roof had let in sand at the

south end until the chamber was nearly full, and only the corners of

the upper part were exposed to the burning of the roof. Probably,

therefore, the burning was due to accident. The tombs were deserted,

the roofs broken in, the chambers almost full of sand. Runaway slaves

and vagabonds taking refuge here would light fires and use the wood,

and thus by accident the great beams would catch fire and be destroyed.

Such seems to have been the source of the burning here; certainly it

had nothing to do with the funeral, as scarcely any of the objects of

wood, ivory, or stone, show any traces of it.

footnote:

1.

[Editor's note: Manetho was a 3rd century BC historian from Ptolemaic

Egypt who wrote several volumes on on history and religion in Greek.

One of his works, Aegyptiaca,

on the history of Egypt, contained a sequence of Egyptian kings which,

while at times erroneous, served as a primary source of ancient

Egyptian chronology until the advent of Egyptology and archaeology in

the 19th century.]

2. For this reading Zer (the bundle of reeds) I am indebted

to Mr. Quibell's study of the sealings from here. M. Amelineau reads

this sign, however, as khent (the group of vases), and always calls

this tomb that of Osiris.

[Continue to chapter 2]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|