|

CHAPTER 5. THE WORSHIP OF OSIRIS (Sections 26-35; figs. 3-7).

26. Legend of Osiris

(p.25). — From the Greek authors we are able to get a fairly connected

account of Osiris. They agree that he came from the north, Plutarch

saying that he was born on the right side of the world, which he

explains as the north; but Diodorus mentions the town from which he

came, namely, Nysa in Arabia Felix, on the borders of Egypt. The Book

of the Dead gives his birthplace as Deddu (Busiris), and this statement

is given by Plutarch on the authority of Eudoxus.

Plutarch gives the

legend of his birth on the first of the intercalary days (see Nut,

sect. 13, No. 13) as the firstborn of the deities Geb and Nut, and says

that on his entrance into the world a voice was heard saying, "The Lord

of all the earth is born," but Diodorus speaks of him as a human king.

The two Greek authors, Plutarch and Diodorus, go on to tell us that on

coming to the throne Osiris proceeded to teach his subjects the arts of

civilization, introducing corn and the vine, and reclaiming the

Egyptians from cannibalism and barbarism. Having reduced his own

kingdom to civilization and order, he gave the government into the

hands of his wife Isis, and travelled southwards up the Nile, teaching

the people as he went. The army that accompanied him was divided into

companies, to each of whom he gave a standard. He was accompanied also

by musicians and dancers, and he introduced the art of music, as well

as the knowledge of agriculture into all the countries through which he

passed. He built Thebes of the hundred Gates, and at Aswan he made a

dam to regulate the inundation of the Nile. He travelled through the

then known world, which included India and Asia Minor, and ended his

peaceful mission by returning happily and in triumph to Egypt.

There he

found everything in order, but his brother Set, consumed with jealousy

and longing to usurp the kingdom, determined on his death. To this end.

Set, with his fellow-conspirators, invited Osiris, under pretence of

friendship, to a banquet, and there exhibited a wooden coffer,

beautifully decorated, which he promised to give to any one whose body

it fitted. All the conspirators in turn lay down in it, but it fitted

none of them, for the measurements had been carefully taken from Osiris

himself without his knowledge. Osiris unsuspectingly entered the coffer

and lay down, whereupon Set and his companions hastily clapped on the

cover, nailed it down, and poured molten lead over it. They then

carried the coffer down to the Nile and threw it into the water.

Here

there comes a discrepancy in the narrative. According to the Metternich

stele, one of the few Egyptian authorities extant, Isis fled to Buto,

in the marshes of the Delta, to escape from Set, and there she brought

forth her son Horus, and remained in that place till he was old enough

to do battle with his father's murderer. Plutarch, however, makes no

mention of this, but says that Isis was at Koptos when she heard of the

death of Osiris, that she cut off a lock of her hair and put on

mourning apparel, and at once instituted a search for her husband's

body.

After many wanderings she arrived at Byblos, and found that the

coffer had lodged in the branches of a tamarisk tree. The tree had grown

round it and had become so large and luxuriant as to attract the notice

and admiration of the king of Byblos, who had it cut down and made it

into a pillar to support the roof of his palace. Isis became nurse to

the infant prince and in reward for her services was permitted to open

the pillar and remove the coffer. She took it away into the desert and

there opened it, and throwing herself on the corpse wept and lamented.

Afterwards she hid away the chest with the body still inside it, and

went to Buto, where her son Horus resided, presumably meaning to return

and bury the dead Osiris. Meanwhile, however, Set, hunting wild boars

by moonlight, came across the coffer and recognized it. In his fury he

flung it open, tore the body to pieces, and scattered the fragments far

and wide. Isis, on her return, found what had occurred. Mourning and

lamenting she searched through the length and breadth of Egypt, burying

each piece of the body in the place where she found it, and raising to

its memory a temple or a shrine.

This is the legend of Osiris

as it was known in Greek times. From what Herodotus says, and from

other indications in mythological texts, it would seem that the

Egyptians, like the Jews and Hindus, had a Supreme Deity whose name it

was not lawful to mention, and who manifested himself, as in Hinduism,

under many forms and names. It appears evident that this Supreme God

was known commonly among the Egyptians by the name of Osiris, but his

true name was hidden from all except those initiated into the

mysteries. In the pyramid texts, Unas says, "O great god, whose name is

unknown," On the stele of Re-ma there is the same expression, "His name

is not known."

(p.26) An observation of Herodotus proves that

Osiris was the chief deity, in Greek times at least, for he says that

though the Egyptians were not agreed upon the worship of their

different gods they were united in the cult of Osiris.

It is

this confusion of names and forms that makes the study of Osiris so

difficult, and I have endeavoured to point out only a few of his many

manifestations.

27. Osiris as a Sun-god.—

Egyptologists have generally looked upon Osiris as a form of the

Sungod, and, indeed, it is usually said that Ra is the living or

day-sun and Osiris the dead or night-sun. This view, however, is not

altogether borne out by the mythology of the Egyptians themselves,

except in so far as that almost every deity of any note was, at some

period of his career, identified with the sun by the worshippers of Ra.

Even in the Book of Am Duat and the Book of Gates, which are entirely

concerned with the journey of the sun during the hours of the night, it

is Ra who passes by in his boat, whose devoted followers gather round

to protect him from danger, to whom the gates, which divide the hours,

are flung open. Osiris, on the contrary, is not the hero of this

nocturnal journey- In the Book of Gates he appears only once, and then

at the entrance of the Sun into the Duat or other world. There he is

seen (Pl.13.) encircling the Duat and supporting Nut, who receives

Ra in her arms (fig.3). It is quite evident here that Osiris and the sun are

two distinct personalities.

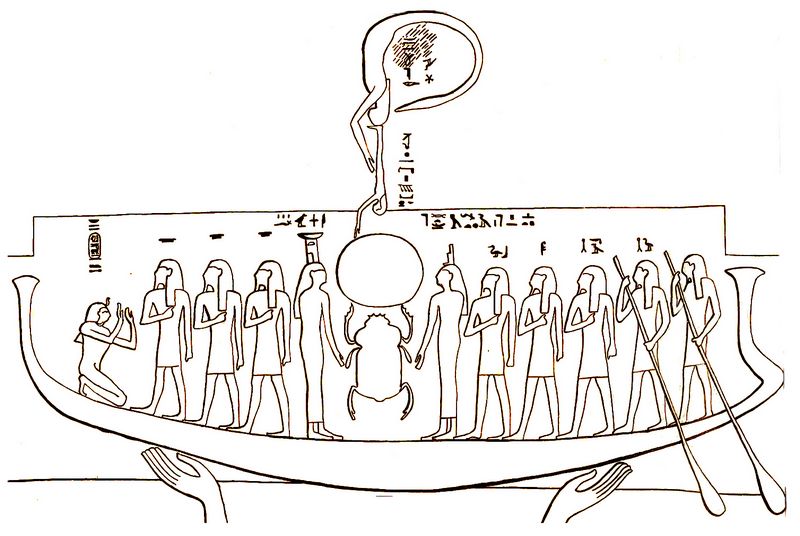

Fig.3:

Detail of inscriptions at the Osireion at Abydos portraying the Book of Gates,

showing Osiris in circular form at top around the inscription of the

Duat, holding the upside-down figure of Nut. (Source: Plate 13, this volume).

In chap. 17 of the Book of the Dead Ra is

identified with Osiris, but the original text and the glosses are so

obscure that it is not possible to make out the true meaning. In the

hvmn to Ra, which comes between chaps.15 and 16, there is a very

definite statement about the night sun, showing that it is Ra himself

and not Osiris. "Thou (Ra) completest the hours of the Night, according

as thou hast measured them out. And when thou hast completed them

according to thy rule, day dawneth." All through the Book of the Dead,

though it is implied that Osiris and Ra are the same, yet there is no

definite statement of the fact. M. Jequier thinks that the whole of the

Book of Am Duat, and particularly the Book of Gates, is an attempt of

the theologians of the XVIIIth and XlXth Dynasties to reconcile the

solar with the Osirian worship.

28. Osiris as the Moon-god.—

Osiris is identified with the moon quite as readily as with the sun.

Chap.65 of the Book of the Dead gives prayers to the moon couched in

precisely the same terms as the petitions to Osiris. "O thou who

shinest forth from the Moon, thou who givest light from the Moon, let

me come forth at large amid thy train .... let the Duat be opened for

me ... let me come forth upon this day." In the Lamentations of Isis

and Nephthys, Osiris is actually identified with the moon. " Thoth ....

placeth thy soul in the barque Maat, in that name which is thine of

God Moon .... Thou comest to us as a child each month" (de Horrack,

Rec. of Past, ii). Again, in the Book of the Dead, chap.8, "I am

the same Osiris, the dweller in Amentet I am the Moon-god who dwelleth

among the gods." Plutarch says that upon the new moon of Phamenoth,

which falls in the beginning of spring, a festival was celebrated which

was called The entrance of Osiris into the Moon.

Another proof

of the connection of Osiris with the moon is that the lunar festivals

of the Month and the Half-month, i.e. the New Moon and the Full Moon,

are specially dedicated to him from very early times; he is also Lord

of the Sixth-day festival (the first quarter of the moon), and the

Tenait (the last quarter) is one of his sacred days, and one specially

observed at Abydos.

The

two ceremonies recorded by Plutarch may

also have a connection with the worship of Osiris Lunus, as the

principal object was made in the form of a crescent. At the funeral of

Osiris, a tree was cut down and the trunk formed into the shape of a

crescent. The other ceremony was more elaborate. "On the 19th of

Pachons they march in procession to the sea-side, whither likewise the

priests and other proper officers carry the sacred chest, wherein is

enclosed a small boat or vessel of gold. Into this they first pour some

fresh water, and then all that are present cry out with a loud voice,

'Osiris is found.' As soon as this ceremony is finished, they throw a

little fresh mould, together with some rich odours and spices, into

this water, mixing the whole mass together and working it up into a

little image in the shape of a crescent, which image they afterwards

dress up and adorn with a proper habit."

Herodotus says that

"pigs were sacrificed to Bacchus, and to the moon when completely full.

When they offer this sacrifice to the moon, and have killed the victim,

they put the end of his tail, with the (p.27) spleen and the fat, into

a caul found in the body of the animal, all of which they burn on the

sacred fire, and eat the rest of the flesh on the day of the full moon.

Those who, on account of their poverty, cannot bear the expense of this

sacrifice, mould a paste into the form of a hog and make their

offering. In the evening of the festival of Bacchus, though everyone be

obliged to kill a swine before the door of his house, yet he

immediately restores the carcase to the hog-herd that sold it to him.

The rest of this festival is celebrated in Egypt to the honour of

Bacchus with the same ceremonies as in Greece." The Grecian ceremonies

being phallic, it is evident that Osiris Lunus was the same deity as

Osiris Generator, and it is this idea that Hermes Trismegistos

expresses when he calls the moon the instrument of birth. Though we

only hear of the sacrifice of pigs to Osiris and the moon in Greek

times, yet we have an evident allusion to it as early as the XIXth

Dynasty. On the sarcophagus of Seti I, and in the tomb of Rameses V,

there are representations of Osiris enthroned, and before him is a boat

in which stands a pig being beaten by an ape. The ape is the emblem of

Thoth, who is one of the chief lunar deities. So in this scene we have

the combination of Osiris and the moon in connection with the pig.

Bronze

figures of Osiris-Lunus are not uncommon. In this form he is never

represented as a mummy, but wears the short kilt, and on his head the

disk of the moon, and sometimes the horns of the crescent. The Sacred

Eye is either in his hand or engraved on the disk, and his name,

Osiris-Aah, is on the pedestal.

29. Osiris as a god of vegetation.

One of the principal forms under which Osiris is worshipped is as a god

of vegetation and generation. Hymns addressed to him are full of

allusions to his generative power. "Nothing is made living without him,

the Lord of Life" (Stele of Re-ma). "Through thee the world waxeth

green in triumph before the might of Neb-er-Zer" (Pap. of Ani).

And, in a hymn of the time of Rameses IX, Osiris is worshipped as the god from whom all life comes:

"Thou

art praised, thou who stretchest out thine arms, who sleepest on thy

side, who liest on the sand, the Lord of the ground, thou mummy with

the long phallus . . . . . . The earth lies on thine arm and its corners upon

thee from here to the four supports of heaven. Shouldst thou move, then

trembles the earth . . . . . [The Nile] comes forth from the sweat of thy

hands. Thou spuest out the air that is in thy throat into the nostrils

of mankind. Divine is that on which one lives. It . . . . . . in thy

nostrils, the tree and its leafage, the reeds and the . . . . . . barley,

wheat, and fruit trees . . . . . . Thou art the father and mother of mankind,

they live on thy breath, they subsist on the flesh of thy body" (Erman,

A.Z., 1900, 30-33). Mr. Fraser (Golden Bough, i, 304) suggests that the

Dad-pillar, the well-known emblem often called the Backbone of Osiris,

" might very well be a conventional representation of a tree stripped

of its leaves, and, if Osiris was a tree-spirit, the bare trunk and

branches of a tree might naturally be described as his backbone."

Osiris,

as the begetter of mankind, is identified with the god Min of Koptos,

the god of generation, and the Phallic festivals celebrated in honour

of Osiris are said by Plutarch to be precisely the same as those in

honour of Bacchus, the similarity of worship being so great that the

two Greek authors who have left us the most detailed account of the

Egyptian religion do not hesitate to speak of Osiris as Bacchus.

The

ritual of the worship of Osiris as a god of vegetation is preserved in

a Ptolemaic inscription at Dendereh. There we have the exact details of

the celebration of the Ploughing Festival to which allusions are made in

texts relating to Osiris. The ritual of Abydos is followed by Koptos,

Elephantine, Kusae, Diospolis of Lower Egypt, Hermopolis, Athribis, and

Schedia; but in Busiris, Heracleopolis Magna, Sais, and Netert it

differed in several particulars.

To take Abydos first, as the chief

place of worship in Upper Egypt, the ceremony was performed in the

presence of the cow-goddess Shenty. In the temple of Seti at Abydos

there is a coloured bas-relief of the goddess in the inner chamber at

the back, and it is probable that this chamber is the Per- Shenty

(House or Chamber of Shenty) where some of the mysteries of the death

and resurrection of Osiris were celebrated. A hollow statuette of pure

gold was made in the likeness of the god—that is to say, of a man

bandaged like a mummy—with the high crown of Upper Egypt. It was to be

a cubit long, including the crown, and two palms wide. Then the

reliquary was of black copper, and its length two palms and three

fingers, its breadth three palms and three fingers, and its height one

palm. On the twelfth of Khoiak four hin of sand and one hin of barley

were put into the statuette, which was then laid in the " garden " with

rushes over and under it.

(p.28) The " garden " was in the Per-Shenty,

and was made of stone, four-square and resting on four pillars. It was

a cubit and two palms in length and breadth, and three palms three

fingers deep inside. The statuette was wrapped in a shet-garment and

decorated with a necklace and a blue flower laid beside it. On the 21st

of Khoiak, nine days after, all the sand and barley was taken out of

the statuette, and dry incense put in its place. The statuette was then

bandaged with four strips of fine linen, and was laid daily in the sun

until the " day of resting in the chamber of Sokar."

On the 25th of

Khoiak the statuette which had been made the previous year was brought

out and laid on a bier, and was buried the same day in the

burial-place called the Arq-heh. This Arq-heh was probably a small

shrine; as Pef-tot-nit (Louvre, A 93) , in describing what he had done

for the temple of Osiris at Abydos, says, "The Arq-heh was of a single

block of syenite."

There was, besides, another mystic ceremony, the

making of what Brugsch, in his translation, calls, "Kiigelchen," but

which should more properly be called cylinders. This mystical ceremony

was, apparently, not performed at Abydos. The cylinders were to be made

of barley, date-meal, dried balsam, fresh resin, fourteen kinds of

sweet-smelling spices, and fourteen kinds of precious stones (according

to the number of the relics of the god) mixed together with water from

the holy lake, and made in the form of little balls, which were wrapped

in sycamore leaves.

At Busiris the ritual was rather

different, as might be expected from the different character of the

god. The festival did not begin till the 20th of Khoiak, when the

barley and sand were put into the "gardens" in the Per-Shenty. Then

fresh inundation water was poured out of a golden vase over both the

goddess and the "garden," and the barley was allowed to grow as the

emblem of the resurrection of the god after his burial in the earth,

"for the growth of the garden is the growth of the divine substance."

The later date is owing to the later harvest of the north.

At Philae

there is a representation of the god lying on his bier, a priest

pouring water over him, and plants growing out of his body (M.A.F.,

tome xiii, pl.40). On the sarcophagus of Ankhrui found at Hawara there

is a similar picture (fig.4) (Petrie, Hawara, pl.2).

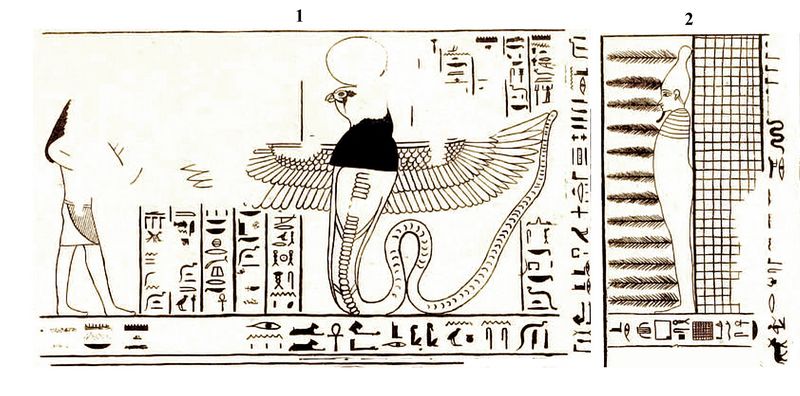

Fig.4:

Tomb of Ankhrui (30th Dyn.) at Hawara, showing (1) top of sarcophagus

lid, with the deceased paying tribute to Horus the hawk; 2) side of

lid, showing mummified Osiris with plants growing out, representing generation (source: Petrie 1889, Hawara, pl.2.)

In the Museum at

Marseilles there is a basalt sarcophagus of the Saite period, on which

is engraved a scene described thus by M. Maspero: "A hillock, rounded

at the top and crowned with four cone-shaped trees; the inscription

tells us that it is Osiris who rests here." This is the same scene as

those already cited, of plants growing from the body of Osiris, though

here the grave only, and not the body, are shown.

Representations

of the resurrection of Osiris are seen at Dendereh, more literally and

not so poetically expressed as at Philae. At Dendereh the god leaps

alive from his bier with the mummy wrappings still upon him (Mar.

Dendereh iv, pls. 72, 90). The little cylinders were to be finished on

the 14th, and placed inside the statuette on the 16th. The linen in

which the statuette was wrapped had to be made in one day, and the

wrapping took place on the 24th. But the 30th of Khoiak was the great

day at Busiris, for then was performed the great ceremony of the

Uplifting of the Dad-pillar. The statuette was buried in a grave called

(by Brugsch) "The Depth above Earth." The Dadpillar was to remain

standing for ten days. This raising of the Dad is a very curious

ceremony, but no satisfactory explanation of it has yet been made. One

of the best-known representations of it is at Abydos in the Hall of the

Osirian mysteries, where Isis and the king, Seti I, are raising the

pillar between them, and there is also a picture of the Dad firmly set

up and swathed with cloth. Still earlier is a scene in the tomb of

Kheru-ef at Assassif, copied by Prof. Erman, where Amenhotep III,

attended by his queen and the royal daughters, is setting up the

Dad-pillar "on the morning of the Sed-festivals," while the sacred

cattle "go round the walls four times" (Brugsch, Thes., 1190).

As

the god of vegetation certain trees and plants must of necessity be

under his special protection; and this we find to be the case. To him

were sacred the tamarisk and the sont-acacia; and at Busiris the

necropolis, in which his effigy was annually buried, was called

Aat-en-beh, Place of Palm-branches. Amt, the Town of the Acacia-trees,

was so completely identified with him in his bull form that it was

called Apis by the Greeks. Diodorus remarks that the ivy was sacred to

Osiris as to Bacchus, and Plutarch says that a fig-leaf was the emblem

of the god, and that his votaries were forbidden to cut down any

fruit-trees or to mar any springs of water.

The ritual of

Dendereh continued in practice until Roman times, for figures of Osiris

made of barley and sand were found by Drs. Grenfell and Hunt at Sheikh

Fadl, the ancient Kynopolis. These figures were roughly modelled to the

desired shape, and were then bandaged after the fashion of a mummy

(p.29) with patches of gilding here and there, to represent the golden

statuette enjoined by the priests of Dendereh. The little cylinders,

which contained sand and barley, but no precious stones, were found

with the figures. The coffin which contained the figure has the hawk

head of Horus, and across the breast is the winged scarab, emblem of

the resurrection. Some were found in a little chamber built of stones,

which seems to correspond with the Arq-heh of Abydos. Two dedicatory

tablets were with the figures, on one of which was the date of the

twelfth year of Trajan. This shows that the ceremony did not die out

till the introduction of Christianity. The ritual was certainly of much

earlier date than the inscription of Dendereh, and a modification of

the ceremony was used in the XVIIIth Dynasty at the burial of a king.

In Ma-her-pra's tomb at Thebes "there was found a symbolic bier with a

mattress, &c., and on the top a figure of Osiris painted on linen.

Earth had been placed on this figure and grains of corn sown and

watered there so that they sprouted " (Arch. Rep. of the E.E.F., 1898-99, p.25).

30. Osiris as god of the Nile.

As the creator of all things living, Osiris is also god of the Nile,

for it is to the river that Egypt owes her fertility. Plutarch, who as

a careful folk-lorist noted all details of ritual, observes that the

Greeks allegorise Saturn into Time and Juno into Air, and in the same

way by Osiris the Egyptians mean the Nile. But he goes on to say that

there are other philosophers who think that by Osiris is not meant the

Nile only but the principle and power of moisture in general, looking

upon this as the cause of generation and what gives being to the

seminal substance. They imagine, he continues, that Osiris is of a

black colour because water gives a black cast to everything with which

it is mixed.

This gives a very curious derivation for the name Kem-ur,

The great black One, under which name Osiris is mentioned several times

in the Book of the Dead. "I flood the land with water, and Kem-ur is my

name" (chap.65). When he is set as Judge of the Dead, his throne

stands upon water, out of which grows the lotus that supports the four

Children of Horus. Offerings almost invariably include the lotus, the

most striking of the water-plants of Egypt. In the Sed-festival of

Osorkon II, the Osirified king, wearing the white crown, stands with a

stream of water pouring from his hands. This is evidently the scene to

which the hymn already quoted (sect. 29) refers, "The Nile comes forth

from the sweat of thy hands." The king as Osiris personifies the Nile,

and wears the crown of Upper Egypt as the country from which the Nile

comes.

31. Osiris as god and judge of the Dead.—

It is in this capacity that Osiris is best known, for everyone is

familiar with the scene of the Weighing of the Heart, where the feather

of Maat and the heart of the deceased are weighed in the scales against

each other. Anubis watches the pointer of the balance, Maat or the ape

of Thoth sits on the upright support, Thoth enters the record on his

tablet; the deceased recites the Negative Confession, and watches the

proceedings anxiously, for near the balance crouches the horrible

animal, Amemt, the Eater of Hearts, ready to devour any heart which

fails to balance the feather exactly. At a little distance the

impartial judge, Osiris, sits enthroned, surrounded by all the

splendour that the artist could contrive. Sometimes another scene is

shown, where the deceased, after passing the ordeal of the Scales in

safety, is led by Thoth to the foot of the throne and there presented

to Osiris. The speech of Thoth and the prayer of the deceased are

given, but the reply of Osiris is never found.

As god of the

dead, there are several points of great interest. According to the

inscription, Horus buried his father with great pomp, and all the

funeral ceremonies in Egypt were supposed to be an exact imitation of

those used for the burial of Osiris. The paintings and sculptures in

the tombs of the kings are distinctly said to be a copy of those with

which Horus decorated the tomb of his father. It is therefore evident

that in the funeral ceremonies used at the entombment of a king or a

high official we shall find some at least of the ritual of the worship

of Osiris as god of the dead.

32. Sacrifices.

One custom which was never omitted at a great funeral was the

sacrificing, and this brings us to one of the most interesting points

of the ritual. That it was to Osiris that the sacrifices were made is

shown by a passage in the Book of the Dead, "Oh Terrible One, who art

over the Two Lands, Red God who orderest the block of execution, to

whom is given the Double [Urert] Crown and Enjoyment as Prince of

Henen-seten" (chap.17). The dead being identified with Osiris would

require sacrifices as gods, and the scene of the slaughter and

dismemberment ofcattle is very common in tombs and temples.

The

question now arises as to whether (p.30) animals were merely

substitutes for human victims. Porphyry says that, according to

Manetho, Amasis abolished human sacrifice at Heliopolis. Diodorus

reports that in ancient times the kings sacrificed red-haired men at

the sepulchre of Osiris, by which may be meant either the traditional

sepulchre of the god, or more probably the tomb of a predecessor of the

royal sacrificer. Plutarch is even more explicit; he quotes Manetho to

the effect that in the city of Eilitheiya it was the custom to

sacrifice men annually and in public, by burning them alive, their

ashes being afterwards scattered. The human victim was called Typho.

Turning to the evidence of the monuments, we find in the temple of

Dendereh a human figure with a hare's head and pierced with knives,

tied to a stake before Osiris Khenti-Amentiu (Mar. Dend. iv, pl.Ivi),

and Horus is shown in a Ptolemaic sculpture at Karnak killing a bound

hareheaded figure before the bier of Osiris, who is represented in the

form of Harpocrates. That these figures are really human beings with

the head of an animal fastened on is proved by another sculpture at

Dendereh (id. ib. pl.Ixxxi), where a kneeling man has the hawk's head

and wings over his head and shoulders, and in another place, a priest

has the jackal's head on his shoulders, his own head appearing through

the disguise (id. ib. pl.xxxi). Besides, Diodorus tells us that the

Egyptian kings in former times had worn on their heads the fore-part of

a lion, or of a bull, or of a dragon, showing that this method of

disguise or transformation was a well-known custom.

In the Book of the Dead,

sacrifices of human beings, or of animals in the place of human

victims, are alluded to frequently, sometimes in set terms. "The Great

Circle of gods at the Great Hoeing in Deddu, when the associates of Set

arrive and take the form of goats, slay them in the presence of the

gods there, while their blood runneth down" (chap.18). "Horus

cutteth off their heads in heaven when in the forms of winged fowl,

their hinder parts on earth when in the forms of quadrupeds or in water

as fishes. All fiends, male or female, the Osiris N. destroyeth them"

(chap.134). "I have come, and I have slain for thee him that

attacked thee. I have come, and I have brought unto thee the fiends of

Set with their fetters upon them. I have come, and I have made

sacrificial victims of those who were hostile to thee. I have come, and

I have made sacrifices unto thee of thine animals and victims for

slaughter" (chap.173).

Plutarch, when describing the

animals reserved for sacrifice, observes that no bullock may be offered

to the gods which has not the seal of the priests first stamped upon

it. He then quotes Castor to the effect that this seal has on it the

impress of a man kneeling with his hands tied behind him and a sword

pointed at his throat.

When we remember what Plutarch says

also about the human victim being called Set, and that according to

Diodorus the victim was red-haired, red being the colour of Set, it is

evident that in the sacrificial animals we have the substitutes for the

human victim, and we may expect to find at the funerals of kings and

great officials that the human sacrifice is continued to a

comparatively late date.

In the sculptures of the XVIIIth

Dynasty tombs of Sennefer, Paheri, Rekh-ma-Ra, Renni, and

Mentu-her-khepesh-ef, a human figure is depicted which has been

recognized by M. Lefebure and others as the sacrificial victim. He is

called the Teknu, and in the tombs of Rekh-ma-Ra and Sennefer he is

wrapped in an ox-skin with only his head visible. In the other tombs

the Teknu crouches down on the sledge on which he is being drawn to the

place of sacrifice. In the sculptures of Mentu-her-khepesh-ef, it

appears that the ritual enforced the strangling of the victim and the

destruction of the body by fire, which supports Plutarch's statement of

the human sacrifice by fire.

In the tomb of Renni (pl.xii) at

El Kab, the victim, here called Kenu, is kneeling upright on a small

sledge, so swathed in cloth that only the outline of the figure is

visible. The sledge is drawn by several men, and the inscription reads

" Bringing the Kenu to this Underworld."

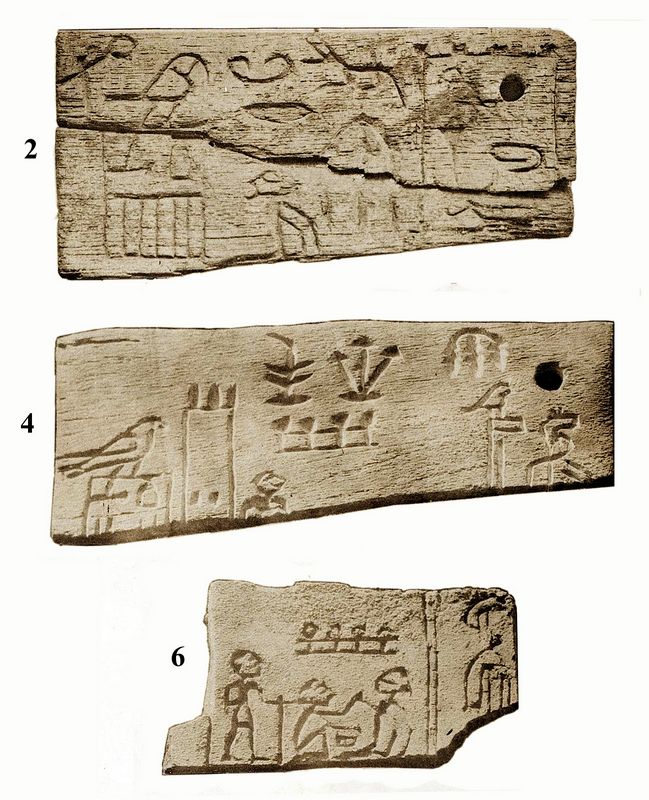

The ebony tablets of

Mena (Petrie, Royal Tombs II, pl.3, Nos. 2, 4, 6) give a sacrificial

scene, in which the victim is a human being (fig.5). Tablet No. 2 gives a bound

captive kneeling before the ka-name of the king; this is probably the

first scene of the sacrificial ceremony of which we get the principal

scene in the other tablets. No. 6 shows a kneeling captive whose arms

are bound behind him; before him sits a man who strikes him to the

heart with a small weapon. Behind the sacrificial priest is a standing

figure holding a staff; and behind the victim are a long pole, and the

hide of an animal, which is in later times the symbol of Ami-Ut, a god

of the dead. Above the scene is the hieroglyph Shesep. No. 4, though

greatly broken, gives many details which have been destroyed in No. 6.

The (p.31) sacrifice has completely disappeared, only the head of the

standing figure remains. Behind him, however, is the sign for a palace

or fortress, and behind that is the ka-name, Aha, of King Mena. We can

also see that the long pole behind the victim is one of the sacred

standards surmounted by a hawk. The sign Mes (Born of, or Child) is

above the hawk, and the sign Shesep occurs again with the hieroglyphs

for South and North above it. It is evident that Shesep, which means "

to receive," has here some special technical meaning.

Fig.5: Ebony tablets of king Mena at Abydos, showing sacrifices (source: Petrie, 1901, pl.3)

There is

also the legend, given by Herodotus, of Hercules being led before

Jupiter to be sacrificed. Herodotus treats the legend with scorn, the

custom being so totally at variance with the mild and gentle character

of the Egyptians of his day. But the truth of the story is at once

apparent when taken in connection with other instances of human

sacrifices. The name Busiris, which Diodorus mentions as a fabulous

king who sacrificed his guests, points to the place where the victims

were immolated; and seeing that the raising of the Dad-pillar was the

chief religious event of the year, it was probably before that object

of worship that the sacrifices were performed.

In the tomb of

Amenhotep II, three human bodies were found, but though there is no

actual proof that these were the victims of sacrifice yet from their

position it seems likely that they had been immolated in honour of the

dead king.

33. In

considering Osiris as god of the dead, it is necessary to remember that

every dead person in later times was identified with him and was called

by his name. In the early dynasties this was not the custom, only kings

being honoured in this manner. Men-kau-Ra is the first of whom we have

any record who bears the name of Osiris, though we shall see further on

(Osiris in the Sed-festival) that the king in his life-time was

identified with the god. In the Xllth Dynasty the custom became

general, and in the XVIIIth it was universal, every dead person being

called Osiris. The complete identification of the king with Osiris is

shown in a sculpture in the tomb of Horemheb (L. D.

iii, 78, a and b),

where Thothmes III is enthroned as Osiris in a shrine, before him are

four human figures called respectively Amset, Hapi, Duamutef, and

Qebhsennuf, with the cartouches of Neb-maat-Ra, Men-kheperu- Ra,

Aa-kheperu-Ra, and Menkheper-Ra. The Weighing of the Heart takes place

in the presence of these royal personages in exactly the same manner as

though they were the gods themselves.

The kingdom of Osiris

was called by the Egyptians the Fields of Aalu. Here the dead lived

again a similar life to that which they had passed upon earth. It was a

land of agriculture and of simple country pleasures. There the wheat

grew to the height of five cubits, the ears being two cubits long,

while the ears of barley were even larger. The South part contained the

Lake of the Kharu fowl, in the North was the lake of the Re fowl. The

whole territory was surrounded by an iron wall (chaps.109 and 149).

The pictures represent a country intersected by canals which form

islands. Here the deceased carries on his agricultural pursuits, he

ploughs with a yoke of oxen, he drives the oxen over the ploughed field

to tread in the seed, and he reaps the corn, which is as tall as

himself. In another part he is paddling in a canoe on one of the

canals, probably for pleasure as he carries his provisions with him

(Papyrus of Nebseni).

This existence, though ideal in some ways, was

not altogether attractive to the ease-loving Egyptian. The hard manual

work, to which the educated classes were unaccustomed, was distasteful,

and yet the Fields of Peace, of which the Fields of Aalu were a part,

were places of happiness and enjoyment. It was to remedy this one

defect, that the models of servants were placed in the graves.

Originally these were servants of all kinds, but they became

stereotyped in the Middle Kingdom, after which time only the farm

labourers, carrying hoe, pick, and basket, are found. These are known

as ushahti figures. The inscription on them is an address from the

deceased, in which he adjures them to take upon themselves the tasks

which Osiris, ruler of the land to which he was going, might command

him to perform.

I cannot refrain from quoting Plutarch on

Osiris as god of the dead. "As to that circumstance of their

mythology, which the priests of the present age seem to have in so much

abhorrence, and of which they never speak but with the utmost caution

and reserve, that Osiris rules over the Dead, and is in reality none

other than the Hades or Pluto of the Greeks—'tis the not rightly

apprehending in what manner this is true, which has given occasion to

all the disturbance which has been raised upon this point; filling the

minds of the vulgar with doubts and suspicions, unable as they are to

conceive, how the most pure and truly holy Osiris should have his

(p.32) dwelling under the earth, amongst the bodies of those who appear

to be dead. And, indeed, this God is removed as far as possible from

the earth, being not susceptible of the least stain or pollution

whatever, and pure from all communication with such Beings as are

liable to corruption and death. As therefore the souls of men are not

able to participate of the divine nature, whilst they are thus

encompassed about with bodies and passions, any farther than by those

obscure glimmerings, which they may be able to attain unto, as it were

in a confused dream, through means of philosophy—so when they are

freed from these impediments, and remove into those purer and unseen

regions, which are neither discernible by our present senses nor liable

to accidents of any kind, 'tis then that this God becomes their leader

and their king; upon him they wholly depend, still beholding without

satiety, and still ardently longing after that beauty, which 'tis not

possible for man to express or think." [Squire's translation.)

34. Osiris in the Sed-festival. It has been observed by Herr Moller (A.Z.

1901, p. 71) that Osiris plays a large part in the ceremonies of the

Sed festival, and it is remarkable that the King himself represents the

god. Of the kings thus depicted we have fourteen, though it is

uncertain whether the sculptures of Seti I as Osiris are intended to

represent the Sed-festival.

King

Dynasty Location

Sources [1]

1. Narmer

Prehistoric El-Kab

Hierakonpolis, Pl.26.

2. Zer

Ist Dyn. Abydos

Royal Tombs.

3. Den

Ist Dyn.

Abydos

Royal Tombs.

4.

Ra-en-user Vth Dyn.

Abusir

A.Z. 1899, Taf.I

5.

Pepy-Mery-Ra Vlth Dyn.

Hammamat L.D. II, 115a.

6. Usertsen III (not contemporary).

Xllth Dyn. Semneh

L.D. Ill, 48,49, 51

7. Amenhotep I XVIIIth Dyn. Karnak

8.

Thothmes III "

" Thebes. Semneh

L.D. 111,36.

" "

" " Abydos Abydos II, Pl.33.

9. Amenhotep III " " Thebes. Soleb L.D. Ill, 74.

10.

Akhenaten " " El Amarna

L.D. Ill, 100.

11.

Rameses I XlXth Dyn. Qurna

L.D. Ill, 131.

12. Seti I " " . Qurna Champollion II, 149

Rossellini III, 57

13.

Rameses II " " El Kab

L.D. Ill, 174.

" " " " Ehnasya

14.

Osorkon II XXIInd Dyn. Bubastis

Festival Hall Osorkon II.

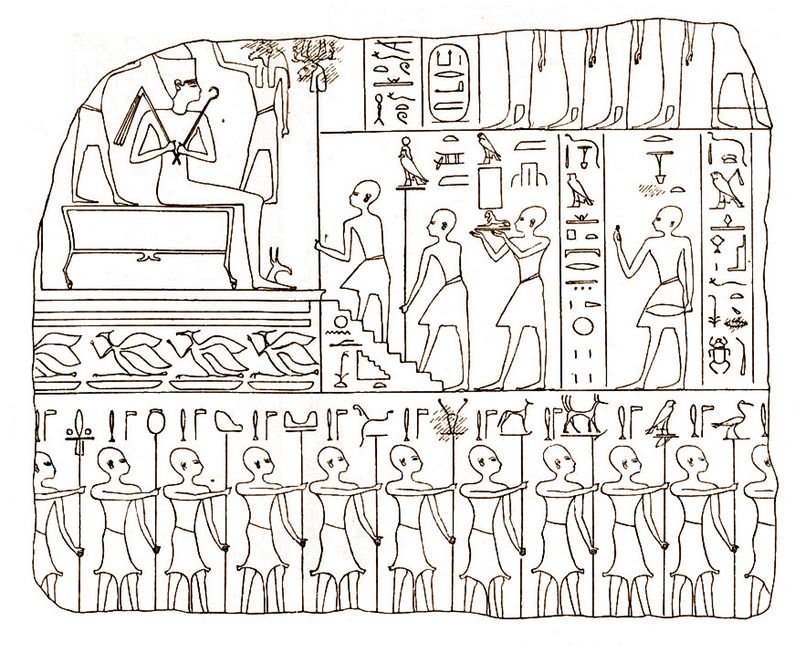

The latest representation, that of Osorkon,

is the best preserved, and gives the ceremony in most detail (fig.6). The King,

robed as Osiris, and holding the crook and scourge, emblems of the god

of the dead. sometimes marches, sometimes is carried, in procession

through the temple. He wears either the white crown or the red crown

according to the part he has to play. During a portion of the ceremony

he is accompanied by the queen and the princesses. The King however is

the chief personage, and to him worship appears to be paid as to a god.

Next in importance to him is the great figure of Upuaut of the South,

which is carried by six priests immediately in front of the living

representative of Osiris. The procession is headed by the Mut neter en

Siuti. The Divine Mother of Him of Siut. "He of Siut" is a title of

Upuaut as god of that city. Following the figure of Upuaut are two

priests carrying small standards, one of Upuaut of the North, and one

of the Joint of Meat which in Ptolemaic times is called Khonsu. This

festival took place on the first day of Khoiak.

Of Rameses II,

whose festivals exceeded in number those of any other king, I know only

two representations. He is enthroned in a shrine and wears the white

crown; his son Kha-em-uast, who stands before him, "satisfies the heart

of the Lord of the Two Lands at the Sed-festival." The date of this at

El Kab is the forty-first year of the king's reign. Another instance of

the Osiride king enthroned is found at Ehnasya.

Seti I is

shown as an Osiride figure in a tomb at Thebes, but it is not certain

that he is celebrating the Sed-festival, as he wears the Atef crown and

not one of the crowns of Egypt. There is also a representation of him

as Osiris in a shrine, with Ptah and Sekhet on one side, Amen-Ra and

Mut on the other; but again there is nothing to show that it is the

Sed-festival.

Rameses I appears in the double shrine which

forms the hieroglyph for the Sed-festival. The shrine is surmounted by

the crouching hawk, and the king wears the white crown.

Akhenaten's

Sed-festival is figured in the style peculiar to that king. He wears

the red crown, and is borne on a litter by priests, while the sun's

disk stretches down innumerable hands to bless him as he passes on his

way. Here again there is a date: the 12th year, the second month of

Pert (Mechir), the eighth day.

Amenhotep III has left two

records of his Sed festival, one at Thebes and one at Soleb. At Thebes

he is enthroned in the two shrines, and wears in one case the white

crown, in the other the red crown. Before him is the emblem of the Ka,

a staff with (p.33) two human arms, surmounted by a hawk, which

presents the notched palm-branch, emblem of millions of years, to the

deified king. Over the arms of the Ka hangs the sign of Life attached

to the signs of the Sed-festival. At Soleb he is seen standing, wearing

the red crown, and accompanied by Queen Thyi and the Seten Mesu, Royal

Children, i.e. the princesses. The standards carried in procession are

five in number, that of Upuaut being foremost. He is also represented

enthroned and wearing the red crown. The date of the festival appears

to be in the month Khoiak.

Thothmes III recorded his

Sed-festival at two places, Semneh and Abydos, or possibly they are the

records of two separate festivals. At Abydos very little remains, only

the figure of the enthroned king with his name, and in front of him the

hide on a pole; some other fragments show that a priest in a

panther-skin stood before him (Petrie, Abydos II,

pl.33). At Semneh he is enthroned in a shrine, and wears the white

crown, and before him are standards, the foremost one being that of

"Upuaut, Leader of the South and the Two Lands," a title of Upuaut of

the South. This is the only standard named. Behind the shrine the

Osirified Thothmes appears again, standing and wearing the red crown;

and in another place he is again standing, wearing the red crown and

attended by the Anmutef priest.

The Sed-festival of Amenhotep

I is sculptured on a slab found at Karnak by M. Legrain. The king is

enthroned, wearing the dress, and bearing the emblems, of Osiris.

At

Semneh we have the Sed-festival of Usertsen III celebrated by Thothmes

III, with, apparently, the same ritual as that of a living king.

Usertsen is enthroned in a shrine which is carried in a boat. He wears

the white crown, and before him are the standards of Upuaut, Neith, the

Joint of Meat, and the Ibis, carried by emblems of Life and Strength.

The standard of Neith is actually foremost, but it appears to take that

place to fill the gap below the standard of Upuaut, which projects very

far forward.

Pepy I has left many records of his

Sed-festivals, but as far as I know there is only one representation,

which is cut on the rocks at Hammamat. He is figured in the double

shrine, on one side wearing the white crown, on the other side with the

red crown. Below is an inscription, "The first time of the

Sed-festival." Another graffito tells us that the festival took place

in his 18th year, on the 27th day of the 3rd month of Shemu (Epiphi).

Of

Ra-en-user's Sed-festival only fragments of the sculpture remain. The

king wears the white crown, but of the standards carried before him all

are destroyed, except one, the Joint of Meat. In another fragment are

the Seten Mesut, Royal Daughters, carried in litters which resemble

sedan-chairs.

King Den's Sed-festival is recorded on a small

ebony tablet found at Abydos. He is enthroned in a shrine, and wears

the double crown. The dancing figure in front I take to be another

scene in the same ceremony; as in the case of Thothmes III, where the

king, vested as Osiris, stands immediately behind the figure of himself

enthroned.

King Zer appears twice enthroned, once with the

white crown, once with the red crown. In each case the standard of

Upuaut precedes him.

The earliest representation of this

festival, where the king appears as Osiris, is on the great mace-head

of Narmer (fig.7). The king is enthroned in a shrine raised on a flight of nine

steps, and wears the red crown. The scene before him is divided into

three registers; in the first are the four sacred standards, that of

Upuaut being foremost; in the second and principal register are three

dancers, and a litter like a sedan-chair, containing a figure closely

wrapped up, which we know from the sculptures of Ra-enuser to be the

Seten Mest, Royal Daughter. Below there are cattle and numerals. In

these scenes we get the earliest representation of this ceremony, and

we can see that the principal points are preserved down to the last

occasion of which we have any record, viz. Osorkon II, a period

extending over four thousand years. The points are three in number:—

1. The king in the robe, and with the emblems, of Osiris, evidently representing the god.

2. The importance of the sacred standards, and the prominent position of the standard of Upuaut.

3. The presence of the Royal Daughters as an integral part of the ceremony.

As

to the second point, some explanation may be found when we turn to the

name of the festival, of which there has as yet been no satisfactory

derivation. On the Palermo Stone there is a record, in the eleventh

year of an unnamed king (called Konig V by Dr. Schafer), of the birth

of the god Sed, the name being determined by the figure which, in later

times, is called Upuaut, a jackal on a (p.34) pedestal, and in front of

him the ostrich feather, emblem of space and lightness, on which,

according to Professor Sethe, the king ascended into heaven at his

death. In the tomb of Kaa (Mar. Mast.

D. 19), and also in another tomb found at Sakkara by Mariette, hitherto

unpublished, the deceased is said to have been "the divine servant of

the god Sed," with the same determinative as on the Palermo Stone. If

the Sed-festival were in honour of the jackal-god Sed, it would be

natural that the figure of the jackal should take a prominent place in

the ceremonies. It is remarkable that in the later sculptures of this

scene, the jackal standard is often carried by an emblematic figure, an

ankh or an uas-sceptre with arms.

Herr Moller has published some curious scenes from a coffin found at Deir el Bahri (A.Z.

1901, p. 71), in which the Sed-festival is depicted, but without any

royal name. The Royal Daughters and the standards of Upuaut are

represented as in the cases already cited; Upuaut is called Lord of

Siut and Leader of the South, and the ostrich feather in front of the

stand has been metamorphosed into a lotus. The closely wrapped figures

in litters have the names Amset, Hapi, and Duamutef, there is nothing

but their likeness to similar figures at Abusir and on the mace-head of

Narmer, to show that they are intended for the princesses; further on,

however, there are other figures in the same attitude and attire,

though not in litters, who are labelled Seten Mesut. The scene of

driving four calves is not known elsewhere in the Sed-festival, though

it is not uncommon in other representations of the worship of the gods.

35. The Da-seten-hetep formula.—

There is one curious point to be noticed in the very common funerary

formula Da-seten-hetep; we find that in the Old Kingdom Osiris is

seldom mentioned. I give a table made up from Lepsius' Denkmaler, Mariette's Mastabas, Davis' Mastaba of Akhethetep, and Rock Tombs of Sheikh Said.

Dynasties:

IVth Vth VIth Total

Anubis alone .

.

15 23 23

61

Anubis and Osiris

1

8 13 22

Osiris

alone . .

1 2

1 4

Anubis with other gods 1 1 1 3

Formula

without a god 1 3

1 5

Total:

19

37 39 95

By Anubis I mean the couchant jackal-god, who appears without name, and with the title Khenti-Neter-seh.

It

is evident from this table that it is not to Osiris that the prayer is

addressed, and I think that the reason is as follows:—

I have

shown that the king, when living, is identified with Osiris in the

Sed-festival, that he was identified after death with the same god is

proved by the coffin of Men-kau-Ra, where the dead king is called "the

Osiris Men-kau-Ra;" and also by the pyramid texts. There is a litany in

the Pyramid of Unas (1. 209, et seq.), which apostrophizes Osiris by

various epithets, and continues, "If he lives, Unas lives; if he does

not die, neither does Unas die; if he is not destroyed, Unas is not

destroyed; if he begets not, Unas begets not; if he begets, then Unas

begets." And it closes with the words, "Thy body is the body of Unas;

thy flesh is the flesh of Unas; thy bones the bones of Unas; as thou

art, so is Unas; as is Unas, so art thou." In the Pyramid of Teta (1.

256) there is the very definite statement that " this Teta is Osiris."

Here,

then, we see that, alive or dead, the King is Osiris and Osiris is the

King. He is the incarnate god upon earth to whom all prayers are

addressed, and who, in connection with Anubis and other gods of the

dead, looks after the welfare of those who have passed out of life.

Therefore it would be mere vain repetition and tautology to introduce

the name of Osiris in the funerary prayers when he has already been

addressed under the title of Seten (king). As time advanced this

appears to be forgotten, and gradually the name of Osiris is inserted,

and that of Anubis ousted, till finally the King and Osiris, one and

the same person, are mentioned together, often to the exclusion of any

other god, in the prayers for the dead.

There is one example

which goes to prove my argument, and which shows that even as late as

the XVIIIth Dynasty the origin of the formula was not completely

forgotten. The inscription is on a wooden statue (Champ. Not.

ii, pp. 719, 720), and runs thus: "May the king grant an offering,"

then come the titles and name of Queen Aahmes-Nefertari, "may she give

life, strength, and health, for the ka of," and then follow the titles

and name of the deceased. Here, then, are the incarnate god and the

deified queen named together as the givers of what is necessary in the

next world.

36. Ceremonies in honour of Osiris.—There are (p.35) several other ceremonies in honour of Osiris, which cannot be classified under any of the foregoing heads.

Plutarch

mentions two which are very similar and may possibly be the same

ceremony as practised in different parts of the country. At the one

which takes place at the winter solstice, "they lead the sacred cow in

procession seven times round her temple, which procession they call in

express terms "The Searching after Osiris." The other "doleful rite"

was to expose to public view "a gilded Ox covered with a pall of the

finest black linen (for this animal is regarded as the living image of

Osiris), and this ceremony they perform four days successively,

beginning on the seventeenth of the abovementioned month (Athyr)."

The

festival of lights is mentioned in the Ritual of Dendereh, and is

described by Herodotus. "There shall be celebrated a voyage on the 22nd

of Khoiak in the 8th hour of the day, when many lamps shall be lighted

near them (the relics) and the gods belonging to them, the list of

whose names runs thus, Horus, Thoth, Anubis, Isis, Nephthys, and the

nineteen Children of Horus. These shall be put into 34 boats.

Furthermore these gods shall be bandaged with the four webs from the

South Town and the North Town (Sais)" (Brugsch). Herodotus describes

the festival as he saw it at Sais. "When they meet to sacrifice in the

city of Sais, they hang up by night a great number of lamps, filled

with oil and a mixture of salt, round every house, the tow swimming on

the surface. These burn the whole night, and the Festival is thence

named The Lighting of Lamps. The Egyptians, who are not present at this

solemnity observe the same ceremonies wherever they be, and lamps are

lighted that night, not only in Sais, but throughout all Egypt.

Nevertheless, the reasons for using these illuminations and paying so

great respect to this night are kept secret."

There are many

allusions to this custom scattered through the religious texts, and all

show that it was a ceremony in honour of Osiris. "O, Osiris, I kindle

the flame for thee on the day of the shrouding of thy mummified body." [Stela of Rameses IV, Piehl, A.Z.,

1885, 16). "The flame for thy ka, O Osiris Khenti- Amentiu, the flame

for thy ka, O chief Kheri-heb Petamenap . . . . . . It protects thee and shines

about thy head . . . . . . . it makes all thine enemies to fall down before thee,

thine enemies are overthrown" (Dumichen, A.Z., 1883, 14-15). At Soleb during the Sed-festival of Amenhotep III, the lighting of a lamp forms part of the function (L. D.

iii, 84); and at an earlier period still, in the Xllth Dynasty, the

kindling of a spark or lamp was evidently one of the chief rites at the

commemorative ceremonies for the dead (Griffith, Siut, pl.viii).

Herodotus

mentions a ceremony which he describes partly from observation and

partly from hearsay, but which seems to be a confused account of some

Osirian rite. "The Egyptians celebrate a certain festival from the day

of Rampsinitus' descent (into Hades) to that of his re-ascension . . .

. . . . The priests every year at that time, clothing one of their

order in a

cloak woven the same day, and covering his eyes with a mitre, guide him

into the way that leads towards the Temple of Ceres [Isis], and then

return, upon which, they say, two wolves come and conduct him to the

Temple, twenty stades distant from the city, and afterwards accompany

him back to the place from whence he came." The garment woven in one

day is probably the same that is ordered in the Ritual of Dendereh,

"the 19th of Khoiak, on which day shall be made the linen for wrapping

the body." The two wolves stand for Upuaut of the South and Upuaut of

the North coming from the temple of Isis to meet the incarnate Osiris.

They conduct him as the "openers of roads."

Firmicus Maternus

gives a description of a ceremony which apparently represents the

burial rites of Osiris. A pine tree was cut down, and the heart of the

tree removed. From this was made an image of Osiris, which was replaced

in the hollow tree as in a tomb, where it remained till the following

year, when it was burned.

[Continue to Chapter 6]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |