|

INTRODUCTORY

(p.1).

The traveller who visits Athens for the first time will

naturally, if he be a classical scholar, devote himself at the outset

to the realization of the city of Perikles. His task will here be beset

by no serious difficulties. The Acropolis, as Perikles left it, is,

both from literary and monumental evidence, adequately known to us.

Archaeological investigation has now but little to add to the familiar

picture, and that little in matters of quite subordinate detail. The

Parthenon, the Propylaea, the temple of Nike Apteros, the Erechtheion

(this last probably planned, though certainly not executed by Perikles)

still remain to us; their ground-plans and their restorations are for

the most part architectural certainties.

Moreover, even outside the

Acropolis, the situation and limits of the city of Perikles are fairly

well ascer-tained. The Acropolis itself was, we know, a fortified

sanctuary within a larger walled city. This city lay, as the oracle in

Herodotus [1] said, ‘wheel-shaped’ about the axle of the sacred hill.

Portions of this outside wall have come to light here and there, and

the foundations of the great Dipylon Gate are clearly made out, and are

marked in every guide-book.

Inside the circuit of these walls, in the

inner Kerameikos, whose boundary-stone still remains, lay the agora.

Outside is still to be seen, with its street of tombs, the ancient

cemetery. Should the sympathies of the scholar extend to Roman times,

he has still, for the making of his mental picture, all the help

imagination needs. Through the twisted streets of modern Athens the

beautiful Tower of the Winds is his constant land-mark; Hadrian, with

his Olympieion, with his triumphal Arch, with his Library, confronts

him at every turn; when he goes to the great (p.2) Stadion to see ‘Olympian’ games or a revived ‘Antigone,’

when he looks down from the Acropolis into the vast Odeion, Herodes

Atticus cannot well be forgotten. Moreover, if he really cares to know

what Athens was in Roman days, the scholar can leave behind him his

Murray and his Baedeker and take for his only guide the contemporary of

Hadrian, Pausanias.

But returning, as he inevitably will, again and

again to the Acropolis, the scholar will gradually become conscious, if

dimly, of another and an earlier Athens. On his plan of the Acropolis

he will find marked certain fragments of very early masonry, which, he

is told, are ‘Pelasgian. As he passes to the south of the Parthenon he

comes upon deep-sunk pits railed in, and within them he can see traces

of these ‘Pelasgian’ walls and other masonry about which his guide-book

is not over-explicit.

To the south of the Propylaea, to his

considerable satisfaction, he comes on a solid piece of this

‘Pelasgian’ wall, still above ground. East of the Erechtheion he will

see a rock-hewn stair-way which once, he learns, led down from the

palace of the ancient prehistoric kings, the ‘strong house of

Erechtheus.’ South of the Erechtheion he can make out with some effort

the ground plan of an early temple ; he is told that there exist bases

of columns belonging to a yet earlier structure, and these he probably

fails to find.

With all his efforts he can frame but a hazy picture of

this earlier Acropolis, this citadel before the Persian wars. Probably

he might drop the whole question as of merely antiquarian interest—a

matter to be noted rather than realized—but that his next experience

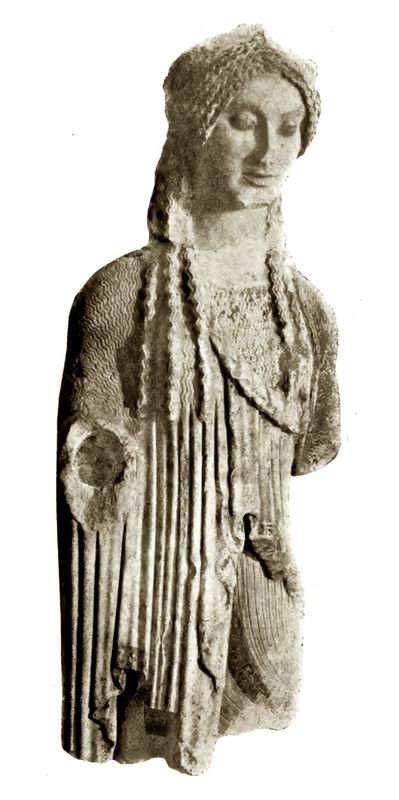

brings sudden revelation. Skilfully sunk out of sight—to avoid

interfering with his realization of Periklean Athens—is the small

Acropolis Museum. Entering it, he finds himself in a moment actually

within that other and earlier Athens dimly discerned, and instantly he

knows it, not as a world of ground-plans and fragmentary Pelasgic

fortifications, but as a kingdom of art and of humanity vivid with

colour and beauty.

The Persian harried them, Perikles left them

to lie beneath his feet, yet their antique loveliness is untouched and

still sovran. They are alive, waiting still, in hushed, intent

expectancy—but not for us. We go out from their presence as from a

sanctuary, and henceforth every stone of the Pelasgian fortress where

they dwelt is, for us, sacred.

Plate 1: Statue of "Maiden" from the Acropolis.

But if he leave that museum aglow with a

new enthusiasm, determined to know what is to be known of that antique

world, the scholar will assuredly be met on the threshold of his

enquiry by difficulties and disillusionment. By difficulties, because

the information he seeks is scattered through a mass of foreign

periodical literature, German and Greek; by disillusionment, because

to the simple questions he wants to ask he can get no clear,

straightforward answer. He wants to know what was the nature and extent

of the ancient city, did it spread beyond the Acropolis, if so in what

direction and how far? what were the primitive sanctuaries inside the

Pelasgic walls, what, if any, lay outside and where? Where was the

ancient city well (Kallirrhoe), where the agora, where that primitive

orchestra on which, before the great theatre was built, dramatic

contests took place?

Straightway he finds himself plunged into a very

cauldron of controversy. The ancient agora is placed by some to the

north, by others to the south, by others again to the west. The

question of its position is inextricably bound up, he finds to his

surprise, with the question as to where lay the Enneakrounos, a

fountain with which hitherto he has had no excessive familiarity ; the

mere mention of the Enneakrounos brings either a heated discussion or,

worse, a chilling silence. This atmosphere of controversy, electric

with personal prejudice, exhilarating as it is to the professed

archaeologist, plunges the scholar in a profound dejection. His concern

is not jurare in verba magistri—he wants to know not who but what is

right.

Two questions only he asks. First, and perhaps to him unduly

foremost, What, as to the primitive city, is the literary testimony of

the ancients themselves, and preferably the testimony not of (p.4) scholiasts and second-hand lexicographers, but of

classical writers who knew and lived in Athens, of Thucydides, of

Pausanias? Second, To that literary testimony, what of monumental

evidence has been added by excavation ?

It is to answer these two

questions that the following pages are written. It is the present

writer’s conviction that controversy as to the main outlines of the

picture, though perhaps at-the outset inevitable, is, with the material

now accessible, an anachronism ; that the facts stand out plain and

clear and that between the literary and monumental evidence there is no

discrepancy. The plan adopted will therefore be to state as simply as

may be what seems the ascertained truth about the ancient city, and to

state that truth unencumbered by controversy. Then, and not till then,

it may be profitable to mention other current opinions, and to examine

briefly what seem to be the errors in method which have led to their

acceptance.

CHAPTER I

The Ancient City, its Character and Limits (p.5)

By a rare good fortune we have from Thucydides

himself an account of the nature and extent of the city of Athens in

the time of the kingship. This account is not indeed as explicit in

detail as we could wish, but in general outline it is clear and vivid.

To the scholar the remembrance of this account comes as a ray of light

in his darkness. If he cannot find his way in the mazes of

archaeological controversy, it is at least his business to read

Thucydides and his hope to understand him.

The account of primitive

Athens is incidental. Thucydides is telling how, during the

Peloponnesian War, when the enemy was mustering on the Isthmus and

attack on Attica seemed imminent, Perikles advised the Athenians to

desert their country homes and take refuge in the city. The Athenians

were convinced by his arguments. They sent their sheep and cattle to

Euboea and the islands; they pulled down even the wood-work of their

houses, and themselves, with their wives, their children, and all their

moveable property, migrated to Athens.

But, says Thucydides [2], this

‘flitting’ went hard with them; and why? Because ‘they had always, most

of them, been used to a country life.’ This habit of ‘living in the

fields, this country life was, Thucydides goes on to explain, no affair

of yesterday; it had been so from the earliest times. All through the

days of the kingship from Kekrops to Theseus the people had lived

scattered about in small communities—‘ village communities’ we expect

to hear him say, for he is insisting on the habit of country life; but,

though he knows the word ‘village’ (κώμη) and employs it in discussing (p.6) Laconia

elsewhere [3], he does not use it here. He says the in-habitants of Athens

lived ‘in towns’ (κατὰ πόλεις), or, as it would be safer to translate

it, ‘in burghs.’

It is necessary at the outset to understand clearly

what the word polis here means. We use the word ‘town’ in

contra-distinction to country, but from the account of Thucydides it is

clear that people could live in a polis and yet lead a country life.

Our word city is still less appropriate; ‘city’ to us means a very

large town, a place where people live crowded together. A polis, as

Thucydides here uses the word, was a community of people living on and

immediately about a fortified hill or citadel— a citadel-community. The

life lived in such a community was essentially a country life. A polis

was a citadel, only that our word ‘citadel’ is over-weighted with

military association.

Athens then, in the days of Kekrops and the other

kings down to Theseus, was one among many other citadel-communities or

burghs. Like the other scattered burghs, like Aphidna, like Thoricus,

like Eleusis, it had its own local government, its own council-house,

its own magistrates. So independent were these citadel-communities

that, Thucydides tells us, on one occasion Eleusis under Eumolpos

actually made war on Athens under Erechtheus.

So things went on till

the reign of Theseus and his famous Synoikismos, the

Dwelling-together or Unification. Theseus, Thucydides says, was a man

of ideas and of the force of character necessary to carry them out. He

substituted the one for the many; he put an end to the little local

councils and council-houses and centralized the government of Attica in

Athens. Where the government is, thither naturally population will

flock. People began to gather into Athens, and for a certain percentage

of the population town-life became fashionable. Then, and not till

then, did the city become ‘great, and that ‘great’ city Theseus handed

down to posterity. ‘And from that time down to the present day the

Athenians celebrate to the Goddess at the public expense a festival

called the Dwelling-together [4].’

One unified city and one goddess, the

goddess who needs no [p.7] name.

Their unity and their greatness the Athenians are not likely to forget,

but will they remember the time before the union, when Athens was but

Kekropia, but one among the many scattered citadel-communities? Will

they remember how small was their own beginning, how limited their

burgh, how impossible—for that is the immediate point—that it should

have contained in its narrow circuit a large town population?

Thucydides clearly is afraid they will not. There was much to prevent

accurate realization. The walls of Themistocles, when Thucydides wrote,

enclosed a polis that was not very much smaller than the modern town;

the walls of the earlier community, the old small burgh, were in part

ruined. It was necessary therefore, if the historian would make clear

his point, namely, the smallness of the ancient burgh and its

inadequacy for town-life, that he should define its limits. This

straightway he proceeds to do. Our whole discussion will centre round

his definition and description, and at the outset the passage must be

given in full. Immediately after his notice of the festival of the ‘

Dwelling-together, celebrated to ‘the Goddess, Thucydides [5] writes as

follows:

" Before this, what is now the citadel was the city, together

with what is below it towards about south. The evidence is this. The

sanctuaries are in the citadel itself, those of other deities as well [6]

(as the Goddess). And those that are outside are placed towards this

part of the city more (than elsewhere). Such are the sanctuary of Zeus

Olympios, and the Pythion, and the sanctuary of Ge, and that of

Dionysos-in-the-Marshes (to whom is celebrated the more ancient

Dionysiac Festival on the 12th day in the month Anthesterion, as us

also the custom down to the present day with the Ionian descendants of

the Athenians); and other ancient sanctuaries also are placed here. And

the spring which is now called Nine-Spouts,

(p.8) from the form given it by the

despots, but which formerly, when the sources were open, was named

Fair-Fount—this spring (I say), being near, they used for the most

important purposes, and even now it is still the custom derived from

the ancient (habit) to use the water before weddings and for other

sacred purposes. Because of the ancient settlement here, the citadel

(as well as the present city) is still to this day called by the

Athenians the City."

In spite of certain obscurities, which are mainly

due to a characteristically Thucydidean over-condensation of style, the

main purport of the argument is clear. Thucydides, it will be

remembered, wants to prove that the city before Theseus was, because of

its small size, incapable of holding a large town population. This

small size not being evident to the contemporaries of Thucydides, he

proceeds to define the limits of the ancient city. He makes a statement

and supports it by fourfold evidence.

The statement that he makes is

that the ancient city comprised the present citadel together with what

is below τέ towards about south. The fourfold evidence is as follows :

1. The sanctuaries are in the citadel itself, those of other deities as

well as the Goddess.

2. Those ancient sanctuaries that are outside are

placed towards this part of the present city more than elsewhere. Four

instances of such outside shrines are adduced.

3. There is a spring

near at hand used from of old for the most important purposes, and

still so used on sacred occasions.

4. The citadel, as well as the

present city, was still in the time of Thucydides called the ‘city.'

We

begin with the statement as to the limits of the city. Not till we

clearly understand exactly what Thucydides states, how much and how

little, can we properly weigh the fourfold evidence he offers in

support of his statement.

"Before this what is now the citadel was the

city, together with what is below it towards about south." The city

before Theseus was the citadel or acropolis of the days of Thucydides,

plus something else. The citadel or acropolis needed then, and needs

now, no further definition. By it is clearly meant not the whole hill

to the base, but the plateau on the summit enclosed by the walls of

Themistocles and Kimon together with the fortification outworks (p.9) on

the west slope still extant in the days of Thucydides. But the second

and secondary part of the statement is less clearly defined. The words

neither give nor suggest, to us at least, any circumscribing line;

only a direction, and that vague enough, ‘ towards about south.’ It is

a point at which the scholar naturally asks, whether archaeology has

anything to say?

But before that question is asked and answered, it

should be noted that from the shape of the sentence alone something may

be inferred. That the present citadel is coextensive with the old city

is the main contention. We feel that Thucydides might have stopped

there and yet made his point, namely, the smallness of that ancient

city. But Thucydides is a careful man, he remembers that the two were

not quite coextensive. To the old city must be reckoned an additional

portion below the citadel (τὸ ὑπ᾽ αὐτήν), a portion that, as will later

be seen, his readers might be peculiarly apt to forget; so he adds it

to his statement. But, by the way it is hung on, we should naturally

figure that portion as ‘not only subordinate to the acropolis, but in

some way closely incorporated with it. In relation to the acropolis,

this additional area, to justify the arrangement of the words of

Thucydides, should be a part neither large nor independent. [7]

Thus

much can be gathered from the text; it is time to see what additional

evidence is brought by archaeology.

Thucydides was, according to his

lights, scrupulously exact. It happens, however, that in the nature of

things he could not, as regards the limits of the ancient city, be

strictly precise. The necessary monuments were by his time hidden deep

below the ground. His first and main statement, that one portion of the

old city was coextensive with the citadel of his day, is not quite

true. This upper portion of the old burgh was a good deal smaller; all

the better for his argument, had he known it!

Thanks to systematic

excavation we know more about the limits of the old city than

Thucydides himself, and it happens curiously enough that this more

exact and very recent knowledge, while it leads us to convict

Thucydides of a real and unavoidable inexactness, gives us also the

reason for his caution. It explains (p.10).

to us why, appended to his statement about the city and the citadel, he

is careful to put in the somewhat vague addendum, ‘together with what

is below it towards about south.’

To us to-day the top of the Acropolis

appears as a smooth plateau sloping gently westwards towards the

Propylaea, and this plateau is surrounded by fortification walls, whose

clean, straight lines show them to be artificial. Very similar in all

essentials was the appearance presented by the hill to the

contemporaries of Thucydides, but such was not the ancient Acropolis.

What manner of thing the primitive hill was has been shown by the

excavations carried on by the Greek Government from 1885-1889. The

excavators, save when they were prevented by the foundations of

buildings, have everywhere dug down to the living rock, every handful

of the débris exposed has been carefully examined, and nothing more now

remains for discovery.

When the traveller first reaches Athens he is so

impressed by the unexpected height and dominant situation of

Lycabettus, that he wonders why it plays so small a part in classical

record. Plato [8] seems to have felt that it was hard for Lycabettus to be

left out. In his description of primitive Athens he says, ‘in old days

the hill of the Acropolis extended to the Eridanus and Tlissus, and

included the Pnyx on one side and Lycabettus as a boundary on the

opposite side of the hill, and there is a certain rough geological

justice about Plato’s description. All these hills are spurs of that

last offshoot of Pentelicus, known in modern times as Turkovouni. Yet

to the wise Athena, Lycabettus was but building material; she was

carrying the hill through the air to fortify her Acropolis, when she

met the crow [9] who told her that the disobedient sisters had opened the

chest, and then and there she dropped Lycabettus and left it...to the

crows.

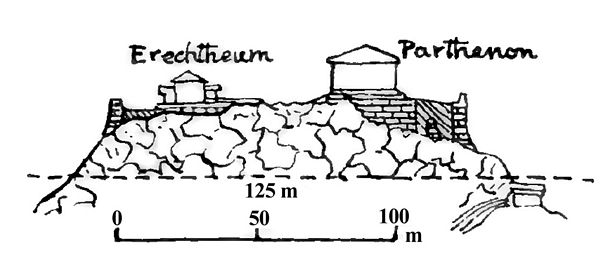

A moment’s reflection will show why the Acropolis was chosen and

Lycabettus left. Lycabettus is a good hill to climb and see a sunset

from. It has not level space enough for a settlement. The Acropolis has

the two desiderata of an ancient burgh, space on which to settle, and

easy defensibility. The Acropolis, as in neolithic days the first

settlers found it, (p.11) was,

it will be seen in fig.1, a long, rocky ridge, broken at intervals [10]. It

could only be climbed with ease on the west and south-west sides, the

remaining sides being everywhere precipitous, though in places not

absolutely imaccessible.

Fig.1: Section drawing of the Acropolis.

Kleidemos [11], writing in the fifth century BC,

says, ‘they levelled the Acropolis and made the Pelasgicon, which they

built round it nine-gated.’ They levelled the surface, they built a

wall round it, they furnished the fortification wall with gates.

We

begin for convenience sake with the wall.’ In tracing its course the

process of levelling is most plainly seen. The question of the gates

will be taken last.

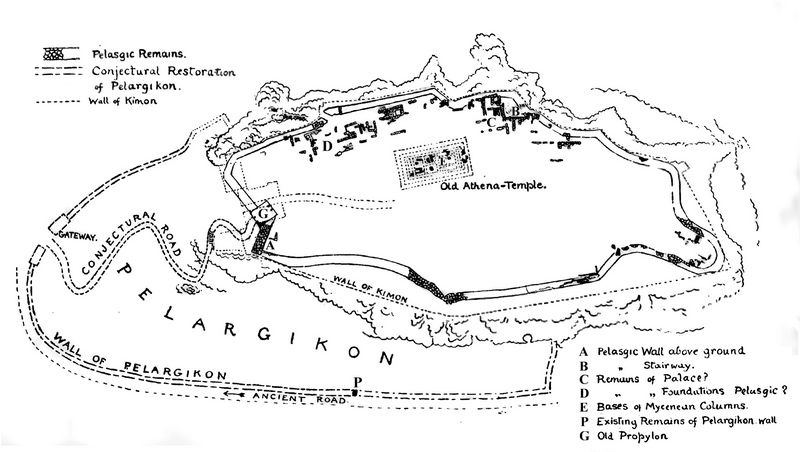

In the plan in fig.2 is shown what excavations

have laid bare of the ancient Pelasgic fortress. We see instantly the

inexactness of the main statement of Thucydides. It is not ‘what is

now the Citadel’ that was the main part of the old burgh, but something

substantially smaller, smaller by about one-fifth of the total area. We

see also that this Thucydides could not know. The Pelasgic wall

following the broken outline of the natural rock was in his days

covered over by the artificial platform reaching everywhere to the wall

of Kimon. At one place, and one only, in the days of (p.13) Thucydides, did the

Pelasgic wall come into sight, and there it still remains above ground,

as it has always been, save when temporarily covered by Turkish

out-works. This visible piece is the large fragment (A), 6 metres

broad, to the south of the present Propylaea and close to the earlier

gateway (G).

In the days of Thucydides it stood several metres high. Of

this we have definite monumental evidence. The south-east corner of the

wall of the south-west wing of the present Propylaea is bevelled

away[12] so as to fit against this Pelasgic wall, and the bevelling can be

seen to-day. This portion of the Pelasgic wall is of exceptional

strength and thickness, doubtless because it was part of the gate-way

fortifications, the natural point of attack.

Save for this one

exception, the Pelasgic walls lie now, as they did in the day of

Thucydides, below the level of the present hill, and their existence

was, until the excavations began, only dimly suspected. Literary

tradition said there was a circuit wall, but where this circuit wall

ran was matter of conjecture; bygone scholars even placed it below the

Acropolis. Now the outline, though far from complete, is clear enough.

To the south and south-west of the Parthenon there are, as seen on the

plan, substantial remains and what is gone can be easily supplied. On

the north side the remains are scanty. The reason is obvious; the line

of the Pelasgic fortification on the south lies well within the line of

Kimon’s wall; the Pelasgic wall was covered in, but not intentionally

broken down. To the north it coincided with Themistocles’ wall, and was

therefore, for the most part, pulled down or used as foundation.

But

none the less is it clear that the centre of gravity of the ancient

settlement lay to the north of the plateau. Although the north wall was

broken away, it is on this north side that the remains which may belong

to a royal palace have come to light. The plan of these remains cannot

in detail be made out, but the general analogy of the masonry to that

of Tiryns and Mycenae leave no doubt that here we have remains of

‘Mycenaean’ date. North-east of the Erechtheion is a rock-cut stairway

(B) leading down through a natural cleft in the rock to the plain

below. As at Tiryns and Mycenae, the settlement on the Acropolis had

not (p.14)

only its great entrance-gates, but a second smaller approach,

accessible only to passengers on foot, and possibly reserved for the

rulers only.

Incomplete though the remains of this settlement

are, the certain fact of its existence, and its close analogy to the

palaces of Tiryns and Mycenae are of priceless value. Ancient Athens is

now no longer a thing by itself; it falls into line with all the other

ancient ‘Mycenaean’ fortified hills, with Thoricus, Acharnae, Aphidna,

Eleusis. The citadel of Kekrops is henceforth as the citadel of

Agamemnon and as the citadel of Priam. The ‘strong house’ of Erechtheus

is not a temple, but what the words plainly mean, the dwelling of a

king. Moreover we are

dealing not with a city, in the modern sense, of vague dimensions, but with a compact fortified burgh.

Thucydides,

though certainly convicted of some inexactness as to detail, is in his

main contention seen to be strictly true— ‘what is now the citadel was

the city. Grasping this firmly in our minds we may return to note his

inexactness as to detail.

By examining certain portions of the

Pelasgic wall more closely, we shall realize how much smaller was the

space it enclosed than the Acropolis as known to Thucydides.

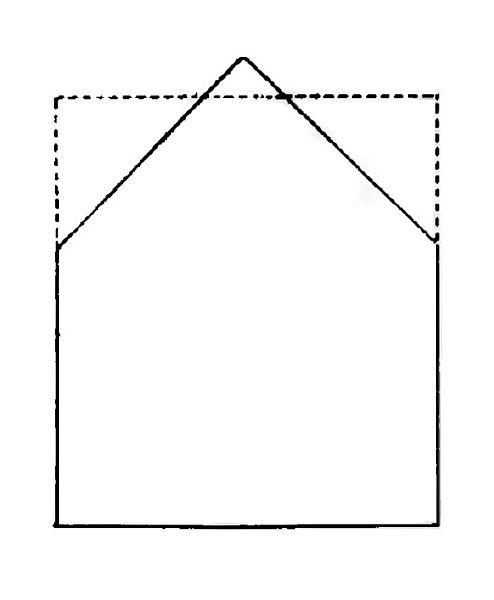

Fig.3: schematic section drawing of shape of Acropolis.

Suppose the sides of the house produced upwards to the height

of the roof-ridge,

and

the triangular space so formed filled in, we have the state of the

Acropolis when Kimon’s walls were completed. The filling in of

those spaces is the history of the gradual ‘levelling of the surface of

the hill, the work of many successive generations. The section in fig.4

will show that this levelling up had to be done chiefly (p.15) on

the north and south sides; to the east and west the living rock is near

the surface. It has already been noted that on the north side of the

Acropolis the actual remains of the Pelasgian wall are few and slight;

but as the wall of Themistocles which superseded it follows the

contours of the rock, we may be sure that here the two were nearly

coincident.

The wall of Themistocles remains to this day a perpetual

monument of the disaster wrought by the Persians. Built into it

opposite the Erechtheum, not by accident, but for express memorial, are

fragments of the architrave, triglyphs and cornice of poros stone, and

the marble metopes, from the old temple of Athena which the Persians

had burnt.

Fig.4: Section drawing of Acropolis showing levelling on north and south sides.

The deposit, it is here clearly seen,

was in three strata. Each stratum consisted of statues and fragments of

statues, inscribed bases, potsherds, charred wood, stones, and earth.

Each stratum, and this is the significant fact, is separated from the

one above it by a thin layer of rubble, the refuse of material used in

the wall (p.16) of Themistocles. The

conclusion to the architect is manifest. In building the wall, perhaps

to save expense, no scaffolding was used; but, after a few courses were

laid, the ground inside way was levelled up, and for this purpose what could be better than the

statues knocked down by the Persians? Headless, armless, their sanctity

was gone, their beauty uncared for.

Fig.5: Section of excavated area northeast of Propylea.

The excavations on the south side of the Acropolis have

yielded much that is of great value for art and for science, for our

knowledge of the extent of the Pelasgian fortification, results of the

first importance. The section in Fig. 7, taken at the (p.17) south-east

corner of the Parthenon, shows the state of things revealed. The

section should be compared with the view in Fig, 6.

The masonry

marked 2 is the foundation, deep and massive beyond all expectation,

laid, not for the Parthenon as we know it, (p.18) but

for that earlier Parthenon begun before the Persian War, and fated

never to be completed. At 4 we see the great Kimonian wall as it exists

to-day, though obscured by its mediaeval casing. All this, if we want

to realize primitive Athens, we must think away. The date of Kimon’s

wall is of course roughly fixed as shortly after 469 B.c., the

foundations of the early Parthenon are certainly before the Persian

War, probably after the date of Peisistratos. We may probably, though

not quite certainly, attribute them to the time of the first democracy,

the activity of Kleisthenes [19], a period that saw the building of the

theatre-shaped Pnyx, the establishment of the new agora in the

Kerameikos, and the Stoa of the Athenians at Delphi.

Fig. 6: Photo of excavation at southeast corner of Parthenon.

Laurium had just

begun to yield silver from her mines. Themistocles, before and after

the war, was all for fortification; the Alkmaeonid Kleisthenes may well

have indulged an hereditary tendency to temple building.

Save for the

clearing of our minds, the date of the early temple-foundations does

not immediately concern us. Their importance is that, but for the

building of the Parthenon, early and late, we should never apparently

have had the great alteration and addition to the south side of the

hill and the ancient Pelasgian wall would never have been covered in.

Let us see how this happened.[20]

We start with nothing but the natural

rock, and on it the Pelasgian wall (1). Over the natural rock is a

layer of earth, marked I. Whatever objects have been found in that

layer date before the laying of the great foundations; these objects

are chiefly fragments of pottery, many of them of Mycenean’

character, and some ordinary black-figured vases.

It is decided to

build a great temple, and the foundations are to be laid. The ground

slopes away somewhat rapidly, so the southern side of the temple is to

be founded on an artificial platform. The trench (b) is dug in the

layer of earth; then, just as on the north side of the hill, no

scaffolding is used, but as: the foundations are laid course by course,

the débris is used as a platform for the workmen. A supporting wall

(2) is required and built of polygonal masonry; it rises course by

course, corresponding (p.19) with

the platform of débris. And then, what might have been expected but was

apparently not foreseen, happens. The slender wall can be raised no

higher and at about the second course the débris unsupported pours over

it, as seen at III. Fig.7: Section of south supporting platform and wall of Parthenon.

The débris, unchecked, fell over as far as the old

Pelasgian wall, How high this originally stood it is not possible now

to say; but, from the fact that outside the supporting wall the layers

of débris again lie horizontally, and from the analogy of another

section taken further west, which need not be discussed here, it is

probable that the old wall was raised by several new courses, and that

the higher ones were of quadrangular blocks, as restored in fig.7.

So

far all that has been accomplished is the raising of the old Pelasgian

wall and a levelling up of the terrace to its new height. That these

terraces were raised step by step with the foundations of the Parthenon

is clear. Between each layer of earth and poros fragments—just as we

have seen in the similar circumstances of the north wall (p.15)—is

interposed a layer of splinters and fragments of the stones used in the

building of the foundations. This can clearly be seen at II. in the

section in fig.7.

Footnotes:

1. Herod, viz. 140.

2. Thucyd. 1. 14 χαλεπῶς δὲ αὐτοῖς, διὰ τὸ ἀεὶ εἰωθέναι τοὺς πολλοὺς ἐν τοῖς ἀγροῖς διαιτᾶσθαι, ἡ ἀνάστασις ἐγίγνετο.

3. Thucyd. 1. 5, 10.

4. Thueyd. τι. 15 καὶ ξυνοίκια ἐξ ἐκείνου ᾿Αθηναῖοι ἔτι καὶ viv τῇ θεῷ ἑορτὴν δημοτελῆ ποιοῦσι.

5. Thucyd.

1. 15 τὸ δὲ πρὸ τούτου ἡ ἀκρόπολις ἡ viv οὖσα πόλις ἦν καὶ τὸ ὑπ᾽ αὐτὴν

πρὸς νότον μάλιστα τετραμμένον" τεκμήριον δέ. τὰ γὰρ ἱερὰ ἐν αὐτῇ τῇ

ἀκροπόλει καὶ ἄλλων θεῶν ἐστί, καὶ τὰ ἔξω πρὸς τοῦτο τὸ μέρος τῆς

πόλεως μᾶλλον ἵδρυται, τό τε τοῦ Διὸς τοῦ Ἰοχυλλ δου καὶ τὸ Πύθιον καὶ

τὸ τῆς Τῆς καὶ τὸ ἐν Λίμναις Διονύσου (ᾧ τὰ ἀρχαιότερα Διονύσια τῇ

δωδεκάτῃ ποιεῖται ἐν μηνὶ ᾿Ανθεστηριῶνι) ὥσπερ καὶ οἱ ἀπ᾿ ᾿Αθηναίων"

Iwves ἔτι καὶ νῦν νομίζουσιν, ἵδρυται δὲ καὶ ἄλλα ἱερὰ ταύτῃ ἀρχαῖα. .

καὶ τῇ κρήνῃ τῇ νῦν μὲν τῶν τυράννων οὕτω σκευασάντων ᾿Εννεακρούνῳ

καλουμένῃ, τὸ δὲ πάλαι φανερῶν τῶν πηγῶν οὐσῶν Καλλιῤῥόῃ

ὠνομασμένῃ---ἐκείνῃ τε ἐγγὺς οὔσῃ τὰ πλείστου ἄξια ἐχρῶντο, καὶ νῦν ἔτι

ἀπὸ τοῦ ἀρχαίου πρό TE γαμικῶν καὶ ἐς ἄλλα τῶν ἱερῶν νομίζεται τῷ ὕδατι

χρῆσθαι. καλεῖται δὲ διὰ τὴν παλαιὰν ταύτῃ κατοίκησιν καὶ ἡ ἀκρόπολις

μέχρι τοῦδε ἔτι ὑπ᾽ ᾿Αθηναίων πόλις.

6. I keep the ms. reading; see

Critical Note.

7. See Dr A. W.

Verrall, The Site of Primitive Athens. Thucydides τι. 15 and recent

explorations, Class. Rev. June 1900, p. 274. In the discussion of the

actual text, I have throughout followed Dr Verrall.

8. Plato Kritias 112.

9. Antigonos, Hist. Mirab. 12.

10. W.

Dorpfeld, ‘‘Ueber die Ausgrabungen auf der Akropolis,” Athen. Mitt. x1.

1886, p. 162.

11. ap. Suidam, s.v. ΓΛπεδα el. ᾿Ηπέδιζον : ἄπεδα, τὰ

ἰσόπεδα. Knreldnuos “ καὶ ἠπέ- διζον τὴν ἀκρόπολιν, περιέβαλλον δὲ

ἐννεάπυλον τὸ Πελασγικόν.

12. Dorpfeld, ‘Die Propylaeen,” A. Mitt. x. 1885, p. 189 and

see the plan of the Propylaea in my Myth. and Mon. Anc. Athens, p. 352.

13. Dorpfeld, ‘Ausgrabungen auf der Akropolis,’ A. Mitt, xr. 1896, p. 167.

14. Dr Kabbadias, Fouilles de lV’Acropole, 1886, Pl. 1. and descriptive text

15. The discussion and interpretation of these figures is reserved for p. 51.

16. 'Ἐφήμερις ᾿Αρχαιολογική, 1866, p. 78.

17. Eph. Arch. 1887, pl. 4.

18. Eph. Arch. 1887, pl. 8.

19. Dorpfeld, ‘Die Zeit des iilteren Parthenon,’ A. Mitt. 1902, p. 410.

20. A. Mitt. 1892, p. 158, pl. viii. and ix.

[Continue to Part 2 of Chapter 1]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|