|

Chapter 1 (part 2) (p.19)

It may seem strange that Kleisthenes, or whoever

built the earlier Parthenon, did not at once utilize the Pelasgian wall

and boldly pile up his terrace against its support. But it must be

remembered that the space between the Parthenon and the Pelasgian wall

was very great; an immense amount of débris would be required for the

filling up of such a space, and it was probably more economical to

build the polygonal supporting-wall nearer to the Parthenon. Anyhow

it

is quite clear that the polygonal wall was no provisional structure.

Its facade shows it was meant to be seen, and that the terrace was

meant for permanent use is clear from the fact that it is connected by

a flight of steps with the lower terrace under the Pelasgian wall

(fig.8). It is clear that whoever planned these steps never thought

that the

lower terrace would be levelled up.

Doubtless whoever filled in the

terrace to the height of the raised Pelasgian wall believed in like

manner that his work was complete. But Kimon thought otherwise. We know

for certain . that it was he who built the great final wall, the

structure that re-mains to-day, though partly concealed by mediaeval

casing (fig.7).

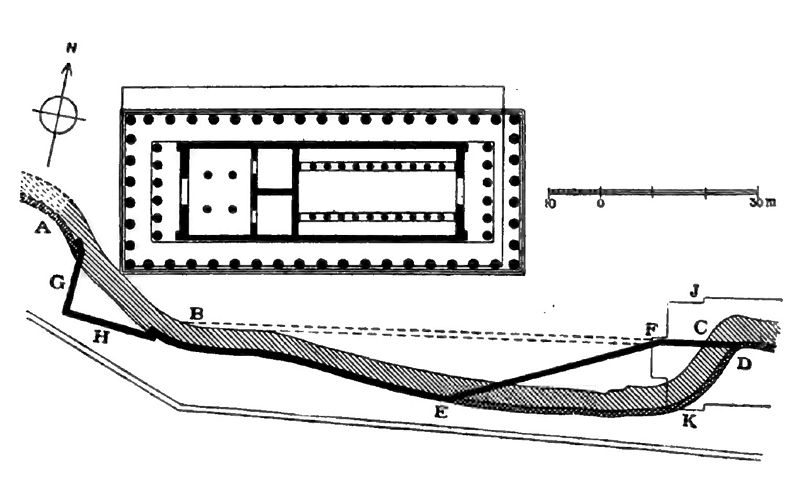

Fig.8: Pelasgian wall with flight of steps.

The fragments of sculpture and architecture that bear traces

of fire are found in the strata marked IV, and there only, for it is

these strata only that were laid down after the Persian War [22].The last

courses of ‘Kimon’s wall’ (5) were laid by Perikles, and he it was who

finally filled in the terrace to its present level (V).

The relation of

the successive walls and terraces is shown by (p.21) the ground-plan in fig.9 [23].

The double shaded lines from A to E and D show the irregular course of

the old Pelasgic wall. The dotted lines

from B to F show the polygonal supporting wall of the first terrace. It

ran, as is seen, nearly parallel to the Parthenon. Its course is lost

to sight after it passes under the new museum, but originally it

certainly joined the Pelasgic wall at C. At B was the stairway joining

the two terraces.

Fig.9: Ground plan of Parthenon and old Pelasgic wall.

At GH there jutted out an independent angular outpost,

and again at EF the new wall is separate from the old; at FD it

coincided with the earlier polygonal terrace wall. Kimon’s wall is

indicated by the outside double lines, and in the space between these

lines and the wall HEK lay the débris of the Persian War. Above that

débris lay a still later stratum, deposited during the building

operations of Perikles.

The various terraces and walls have been

examined somewhat in detail, because their examination helps us to

realize as nothing else could how artificial a structure is the south

side of the Acropolis,

(p.22) and also—a point, to us, of paramount importance—how different was the

early condition of the hill from its later appearance.

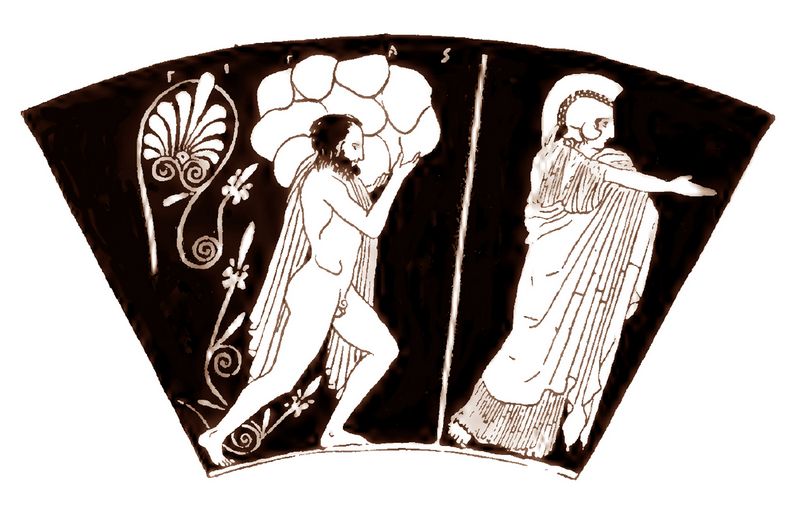

Fig.10: Red-figured vase painting on skyphos showing Athena with giant workman carrying rocks (5th c. BC).

A red-figured vase painter of the fifth century BC.

gives us what would have seemed to a contemporary Athenian a safe and

satisfactory answer—‘There were giants in those days.’ The design in fig.10 is from a skyphos [24] in the Louvre Museum. Athena is about to

fortify her chosen hill. She wears no aegis, for her work is peaceful;

she has planted her spear in the ground perhaps as a measuring rod, and

she has chosen her workman, A great giant, his name Gigas, inscribed

over him, toils after her, bearing a huge ‘Cyclopean’ rock, She points

with her hand where he is to lay it.

Fig.11: Red-figured vase painting on reverse side of skyphos, showing Phlegyas and younger man with staphyle or measuring line (5th c. BC).

On the obverse of the same vase

(fig.11) we have a scene of similar significance. To either side of a

small tree, which marks the background as woodland, stands a man of

rather wild and (p.23) uncouth

appearance. The man to the left is bearded and his name is inscribed,

Phlegyas. The right-hand man is younger, and obviously resembles the

giant of the obverse. He is showing to Phlegyas an object, which they

both inspect with an intent, puzzled air. And well they may. It is a

builder’s staphyle [25], or measuring line, weighted with knobs of lead

like a cluster of grapes; hence its name. Phlegyas [26] and his giant

Thessalian folk were the typical lawless bandits of antiquity; they

plundered Delphi, they attacked Thebes after it had been fortified by

Amphion and Zethus. But Athena has them at her hest for

master-builders. All glory to Athena!

It is not only at Athens that

legends of giant, fabulous work-men cluster about ‘Mycenean’ remains.

Phlegyas and his giants toil for Athena, and at Tiryns too, according

to tradition, the Kyklopes work for King Proetus [27], and they too built

the walls and Lion-Gate of Mycenae [28], At Thebes the Kadmeia [29] is the work

of Amphion and Zethus, sons of the gods, and the fashion in which art

represents Zethus as toiling is just that of our giant on the vase. The

mantle that Jason wore was embroidered, Apollonius of Rhodes [30] tells us,

with the building of Thebes, (p.24)

" Of

river-born Antiope therein

The sons were woven; Zethus and his twin

Amphion, and all Thebes unlifted yet

Around them lay. They sought but

now to set

The stones of her first building. Like one sore

In labour,

Zethus on great shoulders bore

A stone-clad mountain’s crest; and there

hard by

Amphion went his way with minstrelsy

Clanging a golden lyre,

and twice as vast

The dumb rock rose and sought him as he passed. "

Sisyphos, ancient king of Corinth, built on the acropolis of Corinth

his great palace, the Sisypheion. He is the Corinthian double of

Erechtheus with his Erechtheion. Strabo [31] was in doubt whether to call

the Sisypheion palace or temple. Like the old Erechtheion, it was both

fortress and sanctuary. In Hades for eternal remembrance, not, as men

later thought, of his sin, but of his craft as master-builder,

Sisyphos [32], like Zethus, like our giant, still rolls a huge stone up

the slope. Everywhere it is the same tale. All definite record or

remembrance of the building of ‘Cyclopean’ walls is lost; some

hero-king built them, some god, some demi-god, some giant. Just so did

the devil in ancient days build his Bridges all over England.

Tradition

loves to embroider a story with names and definite details. The prudent

Attic vase-painter gives us only a nameless ‘Giant.’ Others knew more.

Pausanias [33] had heard the builders’ actual names and tried to fix their

race. He tells us—just as he leaves the Acropolis -"Save for the portion

built by Kimon, son of Miltiades, the whole circuit of the Acropolis

fortification was, they say, built by the Pelasgians, who once dwelt

below the Acropolis. It is said that Agrolas and Hyperbios...and on

asking who they were, I could only learn that in origin they were

Sikelians and that they migrated to Acarnania."

Spite of the lacuna, it

is clear that Agrolas and Hyperbios are the reputed builders. The

reference to Sicily dates probably from a time when the Kyklopes had

taken up their abode in the island. The two builder-brothers remind us

of Amphion and Zethus, and of their prototypes the Dioscuri [34]. Pliny [35]

tells of a similar pair, (p.25) though he gives to one of them another name. "The

brothers Euryalos and Hyperbios were the first to make brick-kilns and

houses at Athens; before this they used caves in the ground for

houses."

The names of the two ‘Pelasgian’ brothers are, as we know from

the evidence of vase-paintings [36], ‘giant’ names, and Hyperbios is

obviously appropriate. The names leave us in the region of myth, but

the tradition that the brothers were ‘Pelasgian’ deserves closer

attention.

In describing the old wall we have spoken of it as ‘

Pelasgian,’ and in this we follow classical tradition. Quoting from

Hecataeus (circ. 500 BC), Herodotus [37] speaks of land under Hymettus as

given to the Pelasgians "in payment for the fortification wall which

they had formerly built round the Acropolis." Again, Herodotus [38] tells

how when Kleomenes King of Sparta reached Athens, he, together with

those of the citizens who desired to be free, "besieged the despots who

were shut up in the Pelasgian fortification."

A Pelasgian

fortification, a constant tradition that Athens was inhabited by

Pelasgians—we seem to be on solid ground. Yet on a closer examination

the evidence for connecting the name of the fortification with the name

‘Pelasgian’ crumbles. In the one official [39] inscription that we possess

the word is written, not Pelasgikon, but Pelargikon. In like manner, in

Thucydides [40], where the word occurs twice, it is written with an "r".

Pelargikon is "stork-fort," not Pelasgian fort. The confusion probably

began with Herodotus, who was specially interested in the Pelasgians.

Why the old citadel was called "stork-fort" we cannot say— there are no

storks there now—but we have one delightful piece of evidence that, to

the Athenian of the sixth century BC, "stork-fort" was a reality.

Immediately to the south of the present Erechtheion lie the foundations

of the ancient Doric temple [41], currently known by a (p.26) pardonable

Germanism as the "old Athena-temple." For its date we have a certain

terminus ante quem. The colonnade was of the time of Peisistratos; it

was a later addition; the cella of the temple existed before—how much

before we do not know. The zeal and skill of Prof. Dorpfeld for

architecture, of Drs. Wiegand and Schrader for sculpture, have restored

to us a picture of that ancient Doric temple all aglow with life and

colour and in essentials complete [42].

Fig.12: Drawing of sculptures of west pediment of the Old Athena temple.

It is

tempting to turn aside and discuss in detail the whole pediment

composition to which he belongs. It will, however, shortly be seen (p.

37) that our argument (p.27) forbids

all detailed discussion of the sanctuaries of Athena, and the pediments

of her earliest temple have therefore, for us at the moment, an

interest merely incidental.

Thus much, however, for clearness sake may

and must be said. The design of the western pediment fell into two

parts. In one angle, that to the left of the spectator, Herakles is

wrestling with Triton; the right-hand portion, not figured here, is

occupied by the triple figure of "Blue-beard", whose correct

mythological name is probably Typhon [43]. He is no protagonist, only a

splendid smiling spectator. The centre of the pediment, where, in the

art of Pheidias, we should expect the interest to culminate, was

occupied by accessories, the stem of a tree on which hung, as in

vase-paintings, the bow and arrows and superfluous raiment of Herakles.

It is a point of no small mythological interest that in this and two

other primitive pediments the protagonist is not, as we should expect,

the indigenous hero Theseus, but the semi-Oriental Herakles; but this

question also we must set aside; our immediate interest is not in the

sculptured figures of the pediment, but in the richly painted

decoration on the pediment roof above their heads.

The recent

excavations on the Acropolis yielded a large number of painted

architectural fragments, the place and significance of which was at

first far from clear. Of these fragments forty were adorned with two

forms of lotus-flower; twenty had upon them figures of birds of two

sorts. Fragmentary though the birds mostly are, the two kinds (storks

and sea-eagles) are, by realism as to feathers, beak, legs, and claws,

carefully distinguished. The stork (πελαργός) in the Pelargikon is a

surprise and a delight. Was Aristophanes [44] thinking of this Pelargikon

when to the building of his Nephelokokkygia he brought "For brickmakers

a myriad flight of storks."(p.28) One

of the storks is given in fig.13. The birds in the original fragments

are brilliantly and delicately coloured. Their vivid red legs take us to Delphi. We remember Ion [45] with his

laurel crown, his bow and arrows, his warning song to swan and eagle.

"There see! the birds are up: they fly

Their nests upon Parnassus high

And hither tend. I warn you all

To golden house and marble wall

Approach not. Once again my bow

Zeus’ herald-bird, will lay thee low;

Of all that fly the mightiest thou

In talon! Lo another now

Sails

hitherward—a swan!

Away Away, thou red-foot!"

Fig.13: Stork on painted architectural fragments found on Acropolis.

(p.29) In

days when on open-air altars sacrifice smoked, and there was abundance

of sacred cakes, birds were real and very frequent presences. To the

heads of numbers of statues found on the Acropolis is fixed a sharp

spike to prevent the birds perching [46]. They were sacred yet profane.

The

lotus-flowers carry us back to Egypt. The rich blending of motives from

the animal and vegetable kingdom is altogether ‘Mycenaean. Man in art,

as in life, is still at home with his brothers the fish, the bird, and

the flower. After this ancient fulness and warmth of life a pediment by

Pheidias strikes a chill. Its sheer humanity is cold and lonely. Man

has forgotten that "Earth is a covering to hide thee, the garment of

thee."

There are two sorts of birds, two sorts of lotus-flowers, and

there are two pediments. It is natural to suppose, with Dr Wiegand,

that the eagles belonged to the east, the principal pediment. There, it

will later be seen (p. 47), were seated the divinities of the place.

Our pediment decorated the west end, the humbler seat of heroes rather

than gods. There Herakles wrestled with the Triton; there old

Blue-beard—surely a monster of the earlier slime—kept his watch; and

over that ancient struggle of hero and monster brooded the stork.

The

storks themselves are there to remind us that the old name of the

citadel was Pelargikon, and that Pelargikon meant "stork fort"; by an

easy shift it became Pelasgikon [47], and had henceforth an etymologically

false association with the Pelasgoi. Etymologically false, but perhaps

in fact true, for happily the analogy between the Pelargic walls and

those of Mycenae is beyond dispute, and if the ‘Mycenaeans’ were

Pelasgian, the walls are, after all, Pelasgic.

We have seen that both

Thucydides and the official inscription write Pelargikon; their

statements will repay examination. Thucydides, after his account of the

narrow limits of the city before Theseus, returns to the main burden of

his narrative, the crowding of the inhabitants of Attica within the

city walls.

(p.30) "Some few," [48] he says, "indeed

had dwelling places, and took refuge with some of their friends or

relations, but the most part of them took up their abode on the waste

places of the city and in the sanctuaries and hero-shrines, with the

exception of the Acropolis and the Eleusinion, and any other that might

be definitely closed. And what is called the Pelargikon beneath the

Acropolis, to dwell in which was accursed, and was forbidden in the fag

end of an actual Pythian oracle on this wise, 'The Pelargikon better

unused,' was, notwithstanding, in consequence of the immediate pressure

thickly populated."

The passage comes for a moment as something of a

shock. We have been thinking of the Pelargikon as the Acropolis, we

have traced its circuit of walls on the Acropolis, and now suddenly we

find the two sharply distinguished. The Acropolis, though closed, is

surely not cursed. The Acropolis is one of the definitely closed

places, to which the refugees cannot get access; the Pelargikon,

though accursed, is open to them, and they take possession of it; the

two manifestly cannot be coincident. But happily the words "below the

Acropolis" bring recollection, and with it illumination. What is called

the Pelargikon below the Acropolis is surely that appanage of the

citadel which Thucydides in his second clause mentions so vaguely. The

ancient polis comprised not only "what is now the citadel," but also

together with it, "what is below it towards about south"? Thucydides

would have saved a world of trouble if he had stated that "what is

below towards the south" [49] was the Pelargikon; but he does not, probably

because he is concerned with dimensions, not with nomenclature.

The

Pelasgikon meant originally the whole citadel, the ancient city as

defined by Thucydides. This was its meaning in the days of Herodotus.

In the Pelasgikon the tyrants were besieged (p. 25). But by the time of

Thucydides the Acropolis proper, i.e. much the (p.31) larger and more important part of the

old city, had ceased to be "Pelasgic"; the old fortifications were

concealed by the new retaining walls of Themistocles and Kimon. It was

only at the west and south-west that the Pelasgic fortifications were

still visible, hence this portion below the Acropolis took to itself

the name that had belonged to the whole; but this limited use of the

word was at first tentative. Thucydides says, "which is called the

Pelargikon."

This

is quite different from the definite "the Pelasgian

citadel" used by Herodotus. The neuter adjectival form is, so far as I

know, never used of the whole complex of the Acropolis plus what is

below. From Thucydides we learn only that what was called the

Pelargikon was below the Acropolis. "Below" means immediately,

vertically below, for when, in Lucian’s Fisherman [50], Parrhesiades,

after

baiting his hook with figs and gold, casts down his line to fish for

the false philosophers, Philosophy, seeing him hanging over, asks,

"What are you fishing for, Parrhesiades? Stones from the Pelasgikon?"

An

inscription [51]of the latter end of the fifth century confirms the curse

mentioned by Thucydides, and shows us that the Pelargikon was a

well-defined area, as it was the subject of special legislation. "The

king (ie. the magistrate of that name) is to fix the boundaries of the

sanctuaries in the Pelargikon, and henceforth altars are not to be set

up in the Pelargikon without the consent of the Council and the people,

nor may stones be quarried from the Pelargikon, nor earth or stones had

out of it. And if any man break these enactments he shall pay 500

drachmas and the king shall report him to the Council." Pollux [52] further

tells us that there was a penalty of 3 drachmas and costs for even

mowing grass within the Pelargikon, and three officers called paredroi

guarded against the offence. Evidently the fortifications of the

Pelargikon, partially dismantled by the Persians, had become a popular

stone quarry; as evidently the state had no intention that these

fortifications should fall into complete disuse. The question naturally

arises, what was the purport of this surviving Pelargikon, why did it

not perish with the rest of the Pelasgic fortifications ?

The answer is

simple: the Pelargikon remained because it was (p.32) the

great fortification of the citadel gates. According to Kleidemos, it

will be remembered (p. 11), the work of the early settlers was

threefold; they levelled the surface of the citadel, they built a wall

round it, and they furnished the fortifications with gates. Where will

those gates be?

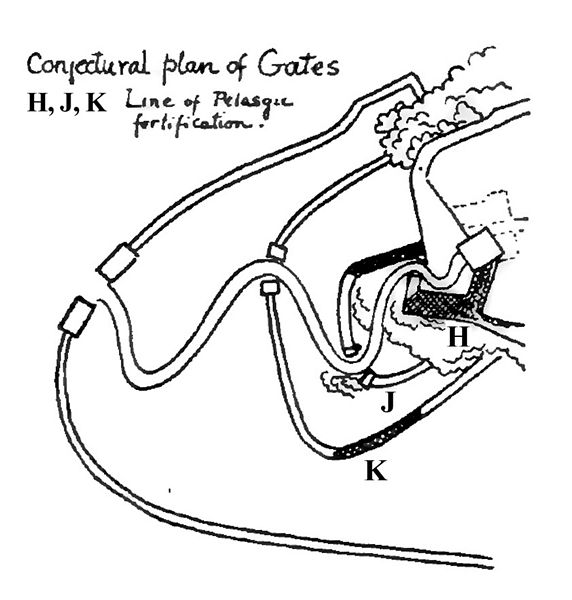

A glance at the section in fig.1 shows that they must

be where they are, ie. at the only point where the rock has an

approachable slope, the west or south-west. We ‘say advisedly

south-west. The great gate of Mnesicles, the Propylaea which remain

to-day, face due west; but within that great gate still remain the

foundations [53] of a smaller, older gate (fig.2, G), built in direct

connection with the great Pelasgic fortification wall, and that older

gate, there before the Persian War [54], faces south-west.

This gate facing

south-west stands on the summit of the hill, and is but one. Kleidemos

(p.11) tells us that the Pelargikon had nine gates. That there should

be nine gates round the Acropolis is unthinkable, such an arrangement

would weaken the fortification, not strengthen it. The successive gates

must somehow have been arranged one inside the other, and the

fortifications would probably be in terrace form. The west slope of

the Acropolis lends itself to such an arrangement, and in Turkish days

this slope was occupied by a succession of redoubts (fig.14).

Fig.14: Sketch of 17th century Athens showing fortifications on Acropolis.

(p.33) Fortified

Turkish Athens is in some ways nearer to the old Pelasgian fortress

than the Acropolis as we see it to-day. We shall probably

not be far wrong if we think of the approach to the

ancient citadel as a winding way (Fig. 15), leading gradually up by

successive terraces, passing through successive fortified gates [55], and

reaching at last the topmost propylon which faced south-west. These

terraces, gates, fortifications, covering a large space, the limits of

which will presently be defined, formed a whole known from the time of

Thucydides to that of Lucian as the Pelargikon or Pelasgikon.

Lucian indeed not only affords our best evidence that, down to Roman

days, a place called the Pelasgikon existed below the Acropolis, but

is also our chief literary source for defining its limits. We expect

those limits to be wide, otherwise the refugees would not have crowded

in.

The passages about the Pelasgikon in Lucian are two. First in the Double Indictment [56], Dike, standing on the Acropolis, sees Pan

approaching, and asks who the god is with the horns and the pipe and

the hairy legs. Hermes answers that Pan, who used to dwell on Mt

Parthenion, had for his services been honoured with a cave below the

Acropolis "a little beyond the Pelasgikon." There he lives and pays his

taxes as a resident. alien. The site of Pan’s cave is certainly known;

close below it was the Pelasgikon. This marks the extreme limit of the

Pelasgikon to the north, for the sanctuary of Aglauros (p.81) by which

the Persians climbed up was unquestionably outside the fortifications.

Fig.15: Plan of gates on western slope of Acropolis.

A

second passage [58] in Lucian gives us a further clue.

Parrhesiades and Philosophy, from their station on the Acropolis, are

watching the philosophers as they crowd up. Parrhesiades says,

"Goodness, why, at the mere sound of the words, 'a ten-pound note,' the

whole way up is a mass of them shouldering each other; some are coming

along the Pelasgikon, others and more of them by the Areopagos, some

are at the tomb of Talos, and others have got ladders and put them

against the Anakeion ; and, by Jove, there’s a whole hive of them

swarming up like bees."

A description like this cannot be regarded as

definite proof; but, taking the shrines in their natural order, it

certainly looks as though in Lucian’s days the Pelasgikon extended from

the Areo-pagos to the Asklepieion. The philosophers crowd up by the

regular approach (ἄνοδος) to the Propylaea; there is not room for them

all, so they spread to right and left, on the right to the Asklepieion,

on the left to the Areopagos; some are crowded out still further on the

right to the tomb of Talos [59], near the theatre of Dionysos; on the left

to the Anakeion [60] on the north side of the Acropolis.

Yet

one more

topographical hint is left us. In a fragment of Polemon [61] (circ. 180

BC), preserved to us by the scholiast on the Oedipus Coloneus of

Sophocles, we hear that Hesychos, the eponymous hero of the Hesychidae,

hereditary priests of the Semnae, had a sanctuary. Its position is thus

described: "it is alongside of the Kyloneion outside the Nine-Gates".

It is clear that in the days of Polemon either the Nine-Gates were

still standing, or their position was exactly known. It is also clear

that, whatever was called the Nine-Gates was near the precinct of the

Semnae. The eponymous hero of their priests must have had his shrine in

(p.35) or

close to the sanctuary of the goddesses. Moreover the Kyloneion or hero

shrine ties us to the same spot. When the fellow-conspirators of Kylon

were driven from the Acropolis, where Megacles dared not kill them,

they fastened themselves by a thread to the image of the goddess to

keep themselves in touch; when they reached the altars of the Semnae

the thread broke and they were all murdered [62]. The Kyloneion must have

been erected as an expiatory shrine on the spot.

When we turn to

examine actual remains of the Pelasgikon on the south slope of the

Acropolis (fig.2), we are met by disappointment. Of all the various

terraces and supporting walls, only one fragment (P) can definitely be

pronounced Pelasgian. The remaining walls seen in fig.16 date between

the seventh and the fifth centuries. The walls marked G in the plan in

Fig. 16, but purposely omitted in Fig. 2, are of good polygonal

masonry, and must have been supporting walls to the successive terraces

of the Pelasgikon; they are probably of the time of Peisistratos [63]. but

may even be earlier. It is important to note that though not ‘

Pelasgic’ themselves they doubtless supplanted previous ‘ Pelasgic’

structures. The line followed by the ancient road must have skirted the

outermost wall of the Pelargikon; later it was diverted in order to

allow of the building of the Odeion of Herodes Atticus. The Pelasgikon

of Lucian’s day only extended as far as the Asklepieion; the earlier

fortification must have included what was later the Asklepieion [64], as it

would need to protect the important well within that precinct.

Thucydides has stated the limits of the ancient city, "what is now the

citadel was the city together with what is below it towards about

south." We nowadays should not question his statement. (p.36) The

remains of the Pelasgian fortifications disclosed by excavation amply

support his main contention, namely, that what is now the citadel was

the city, the conformation of the hill and literary evidence justify

his careful together with what is below it towards about

south.

But, as noted before, the readers of Thueydides were not in our

position, they knew less about the boundaries of the ancient city, and

though they probably knew fairly well the limits of the Pelasgikon,

even that was becoming rather a matter of antiquarian interest. Above

all, they were citizens of the larger city of Themistocles, the Dipylon

was more to them than the Enneapylon. Thucydides therefore feels that

the truth about the ancient city needs driving home. He proceeds to

give evidence for what was, he felt, scarcely self-evident. If we feel

that the evidence is somewhat superfluous, we yet welcome it because

incidentally he thereby gives us much and interesting information as to

the sanctuaries of ancient Athens.

The evidence is, as above stated (p.8), fourfold.

Footnotes:

21. Plut. Vit. Cim, 13,

22.

Unfortunately at the actual time of the excavations the chronology of

the various retaining walls was not clearly evident and the precise

place where many of the fragments excavated were found was not noted

with adequate precision.

23. A, Mitt. xxvu. 1902, p. 398, Fig. 5.

24. F. Hauser, Strena Helbigiana, p. 115.

The reverse was first correctly explained thro’ the identification of

the σταφύλη by Dr O. Rossbach, ‘ Verschollene Sagen und Kulten,’ Neue

Jahrbiicher f, Kl. Altertumswissenschaft, 1901

25. Tl. τι. 7θὅ., ἵπποι σταφύλῃ ἐπὶ

νῶτον ica.

26. See Roscher, Lex. 8.0.

27. Paus, II . 25. 7,

28. Paus. II. 16.

5.

29. Paus. IX. 5. 6.

30. Apoll. Rhod. I. 736.

31. Strabo, σι. 21 ὃ 379. See my

Prolegomena, p. 609.

32. Od. x1. 594. Mr Salomon Reinach in his ‘‘Sisyphe

aux enfers et quelques autres damnés,’ Rev. Arch. 1903, has established

beyond doubt the true interpre-tation of the stone of Sisyphos. 3

33. Paus,

1. 28. 3.

34. Dr Rendel Harris, The Dioscuri, p. 8.

35. Plin. Nat. Hist. VII 57.

36.

For Euryalos see Eph. Arch. 1885, Taf. v. 2and 3. For Hyperbios, Mon.

ἃ. Inst. v1. and vit.

37. Herod. νι. 137 μισθὸν τοῦ τείχεος τοῦ περὶ τὴν

ἀκρόπολίν ποτε ἐληλαμένου.

38. Herod. v. 64 ἐπολιόρκεε τοὺς τυράννους

ἀπεργμένους ἐν τῷ Πελασγικῷ τείχει. All the mss. except Z have

Πελασγικῷ: Z has been corrected to Πελαργικῷ.

39. CI. 4. tv. 2. 27.

6...é€v τῷ Πελαργικῷ...ἐκ τοῦ Πελαργικοῦ.

40. In the best ms. (Laur. C).

-

41. For details of this temple, see: my Myth. and Mon. Anc. Athens, p.

496. For its ground-plan, see below p. 40, Fig, 18.

42. Wiegand-Schrader-Dorpfeld,

Poros-Architektur der Akropolis. For any realization of pre-Periclean

architecture a study of the coloured plates of this work is essential.

43. Typhon and Tritons appear

together on the throne of Apollo at Amyclae. The artistic motives of

this Ionian work are largely Oriental. The conjunction of Typhon and

the Tritons is not, I think, a mere decorative chance, Attention has

not, I think, been called, in connection with this pediment, to the

fact that in Plutarch’s Isis and Osiris (xxxu.) Typhon is the sea into

which the Nile flows (Τυφῶνα δὲ τὴν θάλασσαν, els ἣν ὁ Νεῖλος ἐμπίπτων

ἀφανίζεται. The Egyptian inspiration of the Isis and Osiris no one will

deny, and on this Egyptianized pediment with its lotus-flowers the

Egyptian sea-god Typhon is well in place. His name is doubtless, as

Muss Arnolt Semitic Words in Greek and Latin, p. 59 points out,

connected with Heb. }}D¥ hidden, dark, northern. The sea was north of

Egypt.

44. Ar, Av. 1139 ἕτεροι δ᾽ ἐπλινθοποίουν πελαργοὶ μύριοι.

45. Kur. Jon 154, trans.b y Dr Verrall.

46. See Lechat, Au Musée de l Acropole d’Athénes, p.

215.

47. Any learned blunderer might write Πελασγικόν for Πελαργικόν, but

if Πελασ- γικόν were the original form it would be little likely to be

changed to Πελαργικόν.

48. Thucyd.

τι. 17 τό τε Πελαργικὸν καλούμενον τὸ ὑπὸ τὴν ἀκρόπολιν, ὃ Kal ἐπάρατόν

τε ἦν μὴ οἰκεῖν καί τι καὶ Πυθικοῦ μαντείου ἀκροτελεύτιον τοιόνδε

διεκώλυε, λέγον ὡς τὸ Πελαργικὸν ἀργὸν ἄμεινον, ὅμως ὑπὸ τῆς παραχρῆμα

ἀνάγκης ἐξῳκήθη. Thucydides calls ‘7d Πελαργικὸν ἀργὸν ἀμείνον ᾽ a

final hemistich. Mr A. Β. Cook kindly points out to me that it is in

fact a complete line of the ancient metrical form preceding the

hexameter and known as paroimiac.

49. καὶ τὸ ὑπ᾽ αὐτὴν μάλιστα πρὸς νότον

τετραμμένον.

50. Lucian, Piscator, 46. 2 0.1.4.

51. C.I.A. IV: 2. 27: 6.

52. Poll. On. vu. 101.

53. Dorpfeld, ‘Die Propyliien 1 und 2,’ A. Mitt. x. x. 1885, pp. 38 and 131

and see my Mon. and Myth. Ancient Athens, p. 353.

54. Dorpfeld, A. Mitt. xxvm. 1902, p. 405.

55. The number of these gates is of course

purely conjectural. The sketch in Fig. 15 which I owe to the kindness

of Prof. Dérpfeld gives five only on the western slope. The line of the

walls HJK is suggested by remains of the 6th century B.C. which

probably occupy the site of still earlier Pelasgic fortifications (see

p. 35 note 2). Of the remaining gates one would probably be near where

the Asklepieion was later built and one or more on the north slope.

56. Lucian, Bis Accus. 9 μικρὸν ὑπὲρ τοῦ Πελασγικοῦ.

57. Herod. vit. 52. H. 3

58. Lucian, Piscator 42.

59. See Mon. and Myth. Ancient Athens, p.

299.

60. Op. cit. p. 152.

61. Polem. ap. Schol. Oed. Col. 489 καθάπερ

Πολέμων ἐν τοῖς πρὸς ᾿Ερατοσθένην φησίν, οὕτω.. κριὸν “Hotxw ἱερὸν

ἥρω...ο ὗ τὸ ἱερόν ἐστι παρὰ τὸ Κυλώνειον, ἐκτὸς τῶν ae ΒΡ: The ms. has

Κυδώνιον, the emendation, which seems certain, is due to . O. Mueller.

62. Plut. Vit.

Solon. x1. and Thucyd. 1. 126.

63. For these details about the date of

the various walls I am indebted to Professor Dorpfeld. Dr F. Noack

holds that the nine-gated Pelargikon was not of Mycenaean date but was

built by Peisistratos, the earlier Pelargikon being a much simpler

structure. Prof. Dorpfeld also holds that there was no nine-gated

Pelargikon in Mycenaean days, but he believes that the Peisistratids

only strengthened an already existing fortification, building perhaps

some additional gates. The Enneapylon would then have its contemporary

analogy in the Enneakrounos. See F. Noack, Arne, A. Mitt. 1898, p. 418.

64. A protest was raised against the building of the Asklepieion after it

was begun ; possibly this was because of its encroachment on the

Pelargikon. See A. Koerte, A. Mitt. 1896, pp. 318—831. 3—2

[Continue to Chapter 2]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|