| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Voyage in Lower and Upper Egypt, during the Campaigns of General Bonaparte. Vivant Denon | | | | |

|

Chapter 49: Continuation of the Upper Egypt Campaign.—Kene. (p.245)

On

the 10th [March 1799], we set out again towards Kéné to find out if

there were any Mekkains left there, and where General Desaix could be;

this march was disturbed by these winds which, without clouds, fill the

air with so much sand that it is neither day nor night: our boats being

unable to move, we were obliged to stop a quarter of a league from this

fatal Benhouth of sinister memory. The next day, we arrived at Kéné at

nine o'clock in the morning, where we found letters from General

Desaix, who was unaware of the events in the fleet and our position.

The town was cleared of enemies, and the inhabitants came to meet us.

Fig.1, A (left): Detail of map of upper Egypt, with locations of sites named in the text

(Denon

1802 vol.3, plate 1); B (right:)

Archaeological site map of the early 20th century, including

sites named by Denon (red dots)

(Atlas of the Egyptian

Exploration Fund, ca. 1910).

Kéné

succeeded Kous, as Kous had succeeded Coptos: its situation has this

advantage that it is immediately at the outlet of the desert, and on

the edge of the Nile: it has never been as flourishing as the other

two, because it has only existed since the trade of India was diverted

and almost destroyed, either by the discovery of the route to the Cape

of Good Hope, or by the tyranny of the Egyptian government. Reduced to

the passage of pilgrims, its trade only had any activity at the time of

the march of the great caravan. It is in Kéné that pilgrims from the

Oases, as well as those from Upper Egypt, and some Nubians obtain their

supplies; they take there not only what is necessary for the crossing

of the desert to Cosseir, but also for the journey to Gedda, Medina,

and Mecca, and for the return; because these cities have only a stony

desert [1] as their territory, where people only exist on the strength

of gold; (p.246) so that if, thanks to fanaticism, Mecca has remained a

point of contact between India, Africa, and Europe, it has also become

an abyss in which a population of one hundred and twenty thousand

inhabitants absorbs gold from India, Asia Minor, and all of Africa.

Our

movements on Syria, and our war in Egypt having ruined the caravan of

year six, and dissolved for year seven [2] all those of Europe and

Africa, and the Indians finding no exchange for goods which they had

brought to Mecca, its trade, which had been diminishing for a long

time, must have suffered at this last period a perhaps irreparable

failure. In some cases, when a spring in an old machine breaks, the

machine collapses; we should therefore not be surprised if, interest

joining fanaticism, the Mecca crusade was organized with such rapidity,

and brought against us all the rage that the most violent passions

inspire.

General

Belliard would have pursued the frightened Mamluks and the defeated

Meccans; but we needed ammunition to return to the campaign, and we

absolutely lacked it. We were obliged to fortify the house where we had

lodged in Kéné, and which served as our quarters: we received no news

from anyone, not even from Desaix: the country was covered with

scattered enemies, who arrested and killed our emissaries , or

prevented them from setting out, and kept us isolated in a worrying

manner. The tireless Desaix had pursued the Mamluks as far as Siouth,

had forced Mourat-bey to throw himself into the Oases; he had sent

General Friand to the right bank, to pursue in parallel with him the

hunt for Elli-bey and the scattered bodies of the Mamluks. Desaix came

to find us at Kéné; and we returned to the campaign.

We headed

towards Kous, where the Meccans were, and from where they made

incursions into the villages on both banks, robbing and (p.247)

massacring the Christians and the Copthians, and taking them away, in

order to make them pay a ransom. We left Kéne in the silence and

darkness of the night to try to surprise them: we marched along the

desert to deceive their outposts. When we arrived at the village where

their camp was, we no longer found them; they left there at the same

time that we set out from Kéné: they had taken the desert with the

Mamluks, and had gone to Kittah.

Taking

the desert, in military terms, in Upper Egypt, is not only leaving the

cultivated lands to pass over the sands which border them on the right

and left, but sinking into the gorges which cross the two chains , and

which have mouths, which become positions, kinds of posts, which it is

important to occupy and defend. The Mamluks had the advantage over us

of knowing them all, of knowing the number of fountains that could be

found there. In the valley which leads from Cosséir to the Nile there

are four of these fountains; half a day from Cosséir (the water there

is only good for camels); the second a day and a half from the first;

then that of Kittah, another day and a half away: the latter is very

important when you want to occupy the desert, because it is located at

a point where three paths meet; one of which, heading southwest, leads

to Rédisi; another, going further west, ends at Nagadi; and the third,

to the northwest, brought to Birambar, where there is a fourth

fountain; and from Birambar we arrive by three roads of equal length to

Kous, to Kefth or Coptos, and to Kéné.

Desaix

resolved to block the Mamluks in the desert, or at least to block the

Nile, to hinder their movements, to prevent them from being able to

separate without risking being destroyed, and finally to reduce them to

hunger: he had left three hundred men and cannon at Kéné; he went to

post himself at Birambar (p.248) with infantry, cavalry, and artillery;

and we, with the twenty-first light, went to occupy the passage of

Nagadi: we were imprudent enough to neglect Réclisi, or else we feared

spreading ourselves too thin. If the gorge of Réclisi could have been

occupied, all the beys of the right bank were obliged to surrender;

there remained only Mouratbey to pursue, and no more diversion to fear.

The

hope of seeing Thebes while walking in this direction again made me

joyfully turn my back on Cairo; my destiny was to walk with those who

went the highest; I therefore followed General Belliard; I must join

Desaix soon; The day before we had made a thousand plans for the

future: our farewells were, however, melancholy; this time, our

separation seemed more painful to me: should I think that, so young, it

would be him who would leave me in the career, that it would be me who

would regret it? we separated, and I never saw him again. I was already

a league away when I was joined at a gallop by the brave Latournerie;

he had come back to say goodbye to me; we loved each other very much;

touched by this testimony of tenderness, I was nevertheless struck by

his emotion: we shed a few tears while kissing. The profession of war

can harden cold beings, but its horrors do not wither the sensitivity

of tender souls; the connections formed amid the pains and dangers of

an expedition of the nature of that to Egypt become unalterable; it is

a kind of brotherhood; and when relationships of character further

strengthen these bonds, fate cannot break them without disturbing the

rest of life.

Chapter 50: Antiquities in Kous.—Isfagadi.—Table of Excesses of the French Army. (p.249)

Crossing

Kous, which I had not entered when I had descended the Nile, I found in

the middle of the place the crowning of a gate of beautiful and large

proportions buried up to the simesis; this single vestige, which could

only have belonged to a large building, attests that Kous was built on

the site of Appollinopolis parva. The gravity of this ruin offers a

contrast with everything that surrounds it which says more about

Egyptian architecture than twenty pages of eulogies and dissertations;

this fragment alone appears larger than the rest of the town: half a

league from Kous in the village of Elmécié I found the base of some

sandstone buildings with hieroglyphics. Was it a small town that we

don't know existed? Was it an isolated temple? the degradation of this

monument was too complete for me to be able to give an idea of it by a

drawing, and it was impossible to draw up a plan of any of its parts.

"No.

2.—Picturesque view of the village of Kous, and of the monument seen

in the middle of the square, the only remains of the ancient city of

Apollinopolis parva; the contrast of the gravity of this single

fragment with all the Arab buildings by which it is surrounded is even

more striking in truth than in the engraving: if we excavated in front

of this ruin, we would surely find the remains of the temple of which

this door was part; the raising of this place was the result of

constructions, ruins, and reconstructions of rough barracks Arabs

built in the attics of ancient buildings, to provide more secure

accommodation. What we see above the lintel of this door is still a

remains of the wall of these kinds of structures. The camel skeleton in

front recalls a practice established in the East of not dragging the

bodies of animals that die there out of towns and villages, of allowing

them to infect homes until the crows, the vultures, or the dogs, to

which the inhabitants give no other food, deliver them from the foul

odor of these hideous corpses."

(Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

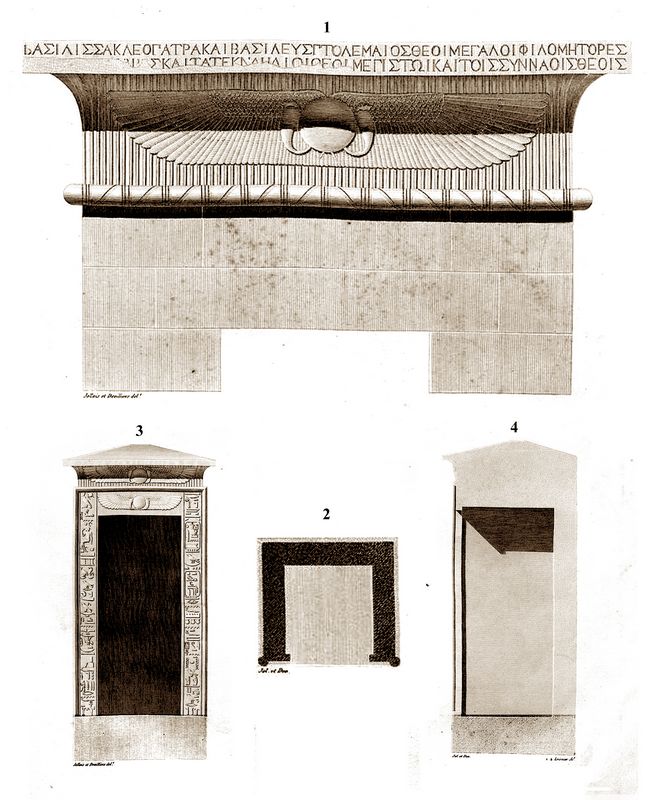

Plate 36-1: Greek Inscription on the ancient gate at Kous:

"Queen Cleopatra and King Ptolemy, great Gods, friends of

their mother and friends of their father, with their children: to the

Sun very great God, and to the Gods worshiped in the same temple."

"No.

1.—Inscription which is on the listel of the crowning of the gate of

Kous on its southern part, which was undoubtedly the entrance to

the

temple of which this gate was part: this dedication, subsequently made

in the time of the Ptolomies, is currently in the state in which I give

it; the citizen Parquoi, with the attention and care of which he is

capable, and with the enlightenment that a long study has acquired for

him, has made to the fragmented letters the dotted-line restitutions

that we see in the third and fourth lines , and the translation which

follows. He granted me the same kindness for the inscription I brought

back from Tintyra, which can be seen in the journal, page 283." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

"Fig.1.

Crowning of an Egyptian door buried in rubble up to the height of the

architrave. It is probable that this door exists in its entirety. As we

were able to approach it very closely, we copied with precision the

winged globe which decorates the cornice. It was also easy for us to

collect the Greek inscription found on the lintel."

"Fig.2. This

figure shows the plan of a monolith similar to those usually contained

in Egyptian sanctuaries. We found analogous ones in the great temple of

Philae. This exists in the lower part of the town of Kous. It is

overturned near a cistern, and appears to have been used as a vase for

watering the animals. It is made of beautiful black granite. The

sculptures with which it is decorated are executed with extreme care

and great precision; it is a precious piece, which demonstrates, in an

unequivocal manner, the high degree of perfection to which bas-relief

sculpture was brought in ancient Egypt."

"Fig.3. Elevation of the

monolithic chapel. All the hieroglyphs which decorate it have been

copied with the greatest accuracy. Its upper part is finished in a

truncated quadrangular pyramid."

"Fig.4. Section of the monolithic chapel."

(Comments by Jollais and Devilliers in vol.4, Description de l'Egypte, 1817)

Another

half-league away, on a small eminence, we see more clearly the base of

a temple absolutely isolated from any other kind of ruins; we can still

see three courses of large sandstone stones which served as a stylus,

and reached the floor of the temple, in front of which was a portico of

six columns engaged at the bottom of their shaft. This monument still

retaining some shape in the projection, I made a small drawing of it.

We walked for another hour and arrived at Nagadi [Naqada], a large and

sad village sitting in the desert; a party of Mamluks had robbed it

twelve hours ago. Before entering the desert, we sent reconnaissance

forward, who took some camels, and killed about thirty Mekkain trampers.

We

went (p.250) to an enclosure which had first been an entrenched

convent; inhabited by Copts, which then became a mosque, and definitely

only served for burials; we lodged there while chasing away the bats

and upsetting the graves. A fort, a desert, tombs! we were surrounded

by everything sad in the world; and if, to escape the impression that

similar objects could bring to our soul, we sometimes went out at night

to breathe for a few moments: our breathing was the only sound that

disturbed the calm of the nothingness that terrified us; the wind

traversing this vast horizon, without encountering any objects other

than us, silent, still reminded us, in the midst of the darkness, of

the immense and sad space by which we were surrounded.

Some

merchants who had had the good fortune to save their junk from the

Mamluks were not very reassured about us. Denounced by the sheikhs of

Nagadi, they brought us presents: we refused them; they were even more

frightened: accustomed to seeing people covered in gold who put them to

work, and seeing us made almost like bandits, they believed that we

were going to rob them; there was no way of hiding their wealth. Our

coat racks had been taken from the boats; we needed linen, so we had

them open their bundles: all hope ended for them; we chose what suited

us, we asked them what what we needed would cost; they told us that it

would be what we wanted; we asked the right price, and we paid; they

were so surprised that they touched their money to find out if it was

really true; people armed and in force who paid! they had traveled all

over Asia and all Africa, and had seen nothing so extraordinary. From

then on we had all their esteem and all their confidence; they came to

make our lunches, (p.251) brought us jams from India and Arabia,

coconuts, and made us the best coffee it was possible to drink: this

mixture of deprivation and research had something spicy; there is no

situation in the world which does not have its enjoyments, I appeal

from this truth to the tombs of Nagadi.

Nagadi (Naqada [3]) is an important point to occupy; it must naturally become the

busiest road in the desert, since it is the shortest in a day; a

messenger can come from Cosséir to Nagadi in two days with a camel, and

in three on foot. As nothing is found at Cosséir, the merchant who

arrives there on his way back from Gidda is in a great hurry to arrive

on the banks of the Nile; the shortest means therefore appear to him to

be the best; he asks for camels from Nagadi which can arrive - on the

sixth day. The price at the time we were there was one strong gourde,

that is to say, five francs. the quintal; each camel carries four: this

price must increase due to the more or less considerable trade, as well

as the price of camels which was then only twenty piastres, instead of

sixty which they were worth before our arrival; which can give the

measure of the misfortune of the circumstances, and how Mecca, Medina,

and Gidda must have suffered from the troubles of Egypt.

We, who

boasted of being more just than the Mamluks, committed daily and almost

necessarily many iniquities; the difficulty of distinguishing our

enemies by shape and color made us kill innocent peasants every day;

the soldiers charged with going out to explore did not fail to take the

poor traders who arrived in caravans for Mekkans; and before justice

was done to them (when there was time to do it to them), two or three

of them had been shot, part of their cargo had been pillaged or wasted,

Jeurs. camels exchanged for those of ours which were wounded; and

(p.252) the profit of all this in the final analysis passed to the

employees, the Copthians, and the interpreters, the bloodsucked of the

army, the soldier constantly having the desire to enrich himself, and

the drum of the gathering or the trumpet of the saddle rider always

made him abandon and forget this project.

The fate of the

inhabitants, for whose happiness we had undoubtedly come to Egypt, was

not preferable: if on our approach, fear made them leave their house,

when they returned after our passage, they found none than the mud of

which the walls are composed. Utensils, plows, doors, roofs, everything

had been used to make a fire for the soup; their pots were broken,

their seeds were eaten, the chickens and pigeons were roasted; All that

remained were the corpses of their dogs, when they had wanted to defend

the property of their masters. If we stayed in their village, we

ordered these unfortunate people to return, under penalty of being

treated as rebels associated with our enemies, and consequently taxed

with double the contribution; and when they surrendered to these

threats, and came to pay the miri, it sometimes happened that their

large number was taken for a gathering, their sticks for weapons, and

they always suffered a few discharges from the riflemen or patrols

before leaving. could have been explained: the dead were buried; and we

remained friends until an opportunity omitted an assured revenge.

It

is true that if they stayed at home, paid the miri, and provided for

all the needs of the army, this would spare them the trouble of the

journey and the stay in the desert; they saw themselves eating their

provisions in order, and were able to eat their share of them, kept

part of their doors, sold their eggs to the soldiers, and had only a

few of their wives or daughters raped: but also they found themselves

guilty for the attachment they had shown us; so that when the Mamluks

succeeded us, they left them not a crown, not a horse, p.253) horse,

not a camel; and often the sheikh paid with his head for the alleged

partiality that was attributed to him. It was very urgent for these

unfortunate people that such a state of affairs should end, and that

another could be organized: but how could this be achieved as long as

the Mamluks did not want to fight, and fanaticized and hungry bands

like the Mekkains would join them?

We learned on the third day

of our stay in Nagadi that three hundred Meccans had resolved, avoiding

the French everywhere, to push all the way across the desert to Cairo,

to get lost in the immense population of this city, until they could

return to their homeland with the caravans, or until some opportunity

was open to them to take revenge on us: we are told that at the moment

of death, their leader had suggested this course to them, and had

advised not to try to fight us again; but the emir's nephew, who had

succeeded him in command, wanting to retain authority and inherit what

remained of the booty made on the French boats, had made them believe

that the treasures he had extracted from them had remained in the

castle of Benhouth, and that, as soon as we were away, he would bring

them back to take them back; but as in the meantime they had to live,

he detached them by platoons, and sent them to maraud into the

villages; what they performed with more or less success; and as a

result the peasants, whose scourge they had become, hunted them down,

and made it like a wolf hunt: encountered by our patrols, they were

picked up, shot, and destroyed like animals harmful to society; This

was how they were shown that Mohammed had not approved their crusade,

and that it was not heaven which had ordered it: this is what is the

subject of one of my paintings; I depicted the moment when the Catholic

peasants brought them to us in the middle of the night to the tombs

where we were staying.

Footnotes:

1. [Author's footnote]: Bread costs eight to ten sous per pound in Mecca, which is an enormous price in the Orient.

2. [Editor's note:] Year 6 (1798) and year 7 (1799) refer to the French Revolutionary calendar, begun in 1792.

3.

[Editor's note:] Naqada was first investigated by Petrie and Quibell in

1895.

The site revealed extensive Pre-dynastic occupations from about

4000-3000 BC, divided into three phases by Petrie which have since seen

various revisions. Burials there and at nearby Ballas also

indicated an intrusive population between the 7th and 10th Dynasties

(i.e., at the juncture of the Old and Middle Kingdoms), with different

burial practices than at other Egyptian sites. For more details, see

Petrie and Quibell, Naqada and Ballas, 1896, Egypt Exploration Fund, London.

.

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|