| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Voyage in Lower and Upper Egypt, during the Campaigns of General Bonaparte. Vivant Denon | | | | |

|

Chapter 48, part 3: Hermontis. - Coptos. - Battle with Mamluks at Benhouth. (p.231)

The

coalition of beys was already broken; Soliman remained in Déir; Assan,

with forty Mamluks, had separated from Mourat at the height of Esnê,

and had gone back to Etfu; all the sheikhs on the left had to separate

further down: and Mourat, alone with his three hundred Mamluks, had to

go down to beyond Siouth; but met at Souhama, below Girgé, by General

Friand, who had destroyed all the gatherings he had formed, he took the

road to Elouah, one of the Oases, where he went (p.232) to wait for

this that fate would ordain for him and for us. There had been two

affairs between the Meccans and the division of General Friand, on the

left bank between Thebes and Kous; six hundred of these adventurers had

perished there: it was said that the sheriff of Mecca himself was

expected, who, with six thousand of his people, was to join the eight

to nine hundred who remained from the first crusade.

Fig.1: General plan of the ruins of the ancient city of Hermontis, and the town modern Erment, from Plate 97, fig.8 of Description de l'Egypte, vol. 1, 1809, drawn by the French engineer Jomard.

"D.

Traces of ancient constructions which appear to have formed a general

enclosure. A. Ancient basin where Nile water still arrives toda.

AC. Old path, directed towards the center of the basin."

(Plate explanations by M. Jomard, in Description de l'Egypte, volume 1, 1809.)

On March 4 [1799], in the morning, we arrived at

Hermontis [1]; we stopped there to wait for news from the Mamluks, the

Meccans, and the rest of our army, scattered at that moment over a

number of points. Reduced to the temple of which I had already seen, I

again went to question the hieroglyphs, and to draw everything which

seemed to me most useful to present to the observations of the Curious

and the learned.

I

was able to better observe the location of the ancient city, which had

had a circumvallation and had several temples. But still temples! not a

public building, not a house that would have had enough substance to

withstand time, not a king's palace! what then was the nation? what

then were the sovereigns? It seems to me that the first was made up of

slaves; the seconds, pious captains; and the priests, humble and

hypocritical despots, hiding their tyranny in the shadow of a vain

monarch, possessing all the sciences and shrouding them in emblem and

mystery, to thus put a barrier between them and the people. The king

was served by priests, advised by priests, fed by them, preached by

them; every morning, after dressing him, they read to him the duties of

the sovereign towards his people, towards his religion; they took him

to the temple; the rest of the day, like the Doge of Venice, he was

never without six councilors, who were still six priests. With such

precautions there could perhaps be no bad kings; but what did the

people gain (p.233) if the priests replaced them? The only two

sovereigns who, according to history, dared to shake off the yoke, who

closed the temples for thirty years, Chephrenes and Cheops, were

regarded and recorded in the annals that the priests wrote, as

rebellious and impious princes.

"Fig.1. Plan of the temple.

"Fig.2.

Elevation on line A B, fig.1. The elevations and the section are shown

with their full height, which was found through excavations. The side

galleries were also restored... The dice which top the columns should

receive figures of Typhon. Due to lack of sufficient data, the walls

were not decorated with the hieroglyphic paintings which probably

covered them.

"Fig.3. Longitudinal elevation on line D C, fig.

1. (See the observations in Figure 2.) Note. The cornice of the

intermediate construction being partly overturned, it was restored with

its listel; but it was made too low by the height of this same listel,

to consult the rule of analogy, according to which the cornice and the

architrave are always of equal height.

"Fig.4. Section taken on line E F, fig. 1. (See observations in Figure 2.)

(Plate explanations by M. Jomard, in Description de l'Egypte, volume 1, 1809.)

The

Palace of the Hundred Rooms, the only palace mentioned in the history

of Egypt, was the work of a new form of government where the priests

could not have the same influence. These famous canals, of which

history speaks to us so sumptuously, have preserved no magnificence, no

dike, no lock, no entanglement: what I have encountered of shoulders

and quays on the banks of the Nile are small works in comparison with

these colossal and immortal temples whose circumvallations occupied a

large part of the site of the cities. The Jesuits of Paraguay could

perhaps have given us the secret or the example of the system of this

theocratic domination; and, in this case, I would only see in this rich

country of Egypt a mysterious and dark government, weak kings, a sad

and unhappy people.

On the 6th, we set out to meet Osmanbey, who

was said to have crossed the Nile at Kéné. I had the pain of crossing

the site of Thebes, and of experiencing even more privations there than

the first time: without measuring a column, without drawing a view,

without approaching a single monument, we followed the edges of the

Nile, equally distant from the temples of Medinet-a-Bou, Memnonium, the

temples of Kournou, which I left on my left, the temples of Luxor and

Karnaq, which I left on my right; temples! more temples, still temples!

and not a vestige of these hundred gates so vain and so famous, no

walls, no quays or bridges, no thermal baths, no theaters, not a

building of public utility or convenience: I observed (p.234)

carefully, I even searched, and I saw only temples, walls covered with

obscure emblems, hieroglyphics which attested to the ascendancy of the

priests who still seemed to dominate all these ruins. and whose empire

still obsesses my imagination.

Four

villages and as many hamlets, in the middle of vast fields, now replace

this incomprehensible town, like a few wild shoots recall the existence

of a tree famous for the majesty of its shade or the sweetness of its

fruits. Leaving this famous ground with regret, we stopped in the

western suburbs, the Necropolis district, where I found the inhabitants

of Kournou, who once again disputed with us the entrance to the tombs,

which had become their asylum; we would have had to kill them to teach

them that we did not want to harm them, and we did not have time to

start the discussion: we were content to block them during a small meal

that we had on the location of their retirement; I took advantage of

this moment to draw the desert and the exterior of these habitats of

death.

Towards

the evening one of our spies reported to us that the Meccans, united

with Osman-bey, were waiting for us entrenched at. Benhoute, three

leagues ahead of Kéné; that they had cannon, and were resolved to make

war and attempt a battle; they added that they had stopped several of

our boats on the Nile, and that after a stubborn fight, in which many

peasants and Meccans had been killed, the French had succumbed to their

numbers and had. were all massacred. We came to sleep on the banks of

the river: we had to cross it to meet the enemy; we waited for our

boats which followed. We saw, beyond any doubt, that we were being

observed from the other bank; every moment armed horsemen arrived and

left: we made a retrograde march to meet our convoy, which we soon

joined; the whole (p.235) rest of the day was spent on our passage,

which we made to el-Kamontéh. On March 8, we set out; on our arrival in

Kous we were confirmed the story of the day before.

Kous,

placed at the entrance to the mouth of the desert which leads to

Bérénice and Cosséir, still has some appearance on the southern side;

its immense melon plantations, its gardens, quite abundant, must make

it seem delicious to the inhabitants of the banks of the Red Sea, and

to thirsty travelers who have just crossed the desert; it succeeded

Copthos by its commerce and by its catholicity: because the Copthians

are still the most numerous inhabitants. Their zeal gave us all the

information they had been able to collect; they accompanied us with

their persons and their wishes to the confines of their territory.

I

was struck by the sincere interest of the sheikh, who, believing that

we were heading towards assured death, gave us the most detailed

advice, without hiding any of our dangers, warned us with the most

perfect intelligence about everything that could to make them less

fatal, followed us as far as he could, and left us with tears in his

eyes. Desaix had been at Kous for eight days; he had seen the sheikh a

lot; and this tender interest that was shown to us was a very natural

result of the advantageous idea that he had given of his loyal and

communicative character, of this gentle and constant fairness which

later earned the nickname àejusle, the most beautiful title that a

victor has ever obtained, a foreigner arriving in a country to wage war

there. We could not imagine anything about these boats, about this

fight; we were far from guessing the importance of the report that had

been made to us: we were only four leagues from the enemy; an hour

after passing Kous we saw on our right, at the foot of the desert, the

ruins of Coptos [2], famous in the fourth century for its oriental trade;

we only recognize its ancient splendor at the height of the mountain of

rubble (p.236) with which it is surrounded, and which still

indicates how great was the location it occupied. The ancient city is

now as dry and as disinhabited as the desert on whose edge it sits.

"Fig.5. Frieze composed of triglyphs, bull's heads and floral motifs, found in the ruins of Coptos."

"Fig.6.

Figure with Isis hairstyle. She carries bouquets of lotuses in both

hands which she presses to her heart. Her clothing consists of a kind

of petticoat attached above the hips by a belt whose ends hang

forward."

"Fig.7. Figure similar to the previous one, except

that the lotuses in her hands are still only in bud. Before her is an

arrangement of blooming lotus flowers and buds."

"Fig.8. Ornament of lotus stems and flowers, which appears to be a Greek work in imitation of the Egyptians."

"Fig. 9 Bas-relief taken from a section of column."

(Plate explanations by Jollais and Devilliers, in Description de l'Egypte, volume 4, 1817.)

We

had barely passed Coptos when someone came to tell us that the enemy

was on the march: we stopped, and after a light meal we started moving

again to join the enemy. We soon saw its flags; their development

occupied a line of more than a league: we continued to march in the

order we had taken, that is to say, in a square battalion, flanked by a

single piece of cannon of three, and fifteen cavalry men; we looked

like a point about to touch a line: we soon heard cries, and we found

ourselves at a village that the end of their development had come to

occupy; we. detached skirmishers who at the same moment found

themselves mixed hand to hand with them: despite some effective

discharges from our piece, they did not retreat; their valor and

dedication made up for the shortage of weapons among them.

After

this outpost had been destroyed rather than repulsed, more resistance

was found in the villages, where the walls and a few firearms gave them

some equality in the combat; However, we pushed them back to under

another village a quarter of a league further on: at this moment, the

Mamluks began to parade, and to appear to want to charge our right to

create a diversion from the advantage we were gaining over their

coalition; we marched straight towards them, without stopping or even

weakening the fight that the hunters were waging against the Meccans;

our smooth march and a few cannon shots delivered us from the

neighborhood of the Mamluks, who did not go there in as good faith as

the Meccans, and only wanted to try if the number of the latter and

their bravery would detach enough soldiers from the great squared so

that it could be attacked with advantage.

After having dislodged

the infantry from the second village, we (p.237) found ourselves in a

small plain which preceded Benhoute, where we knew that the large enemy

force was entrenched, and where all those we had were still gathered

together. already beaten. We fully expected a bloody fight; but not to

be cannonaded by a battery in order, which sent us both grapeshot and

cannonballs, which reached our quarter and even overtook it. Death

hovered around me; I saw her all the time; in the space of ten minutes

that we were arrested, three people were killed while I was talking to

them: I no longer dared to speak to anyone; the last was hit by a ball

which we both saw arriving plowing the ground and appearing at the end

of its movement; he raised his foot to let him pass, a final jerk of

the ball hit him in the heel and tore all the muscles in his leg;

injury from which this young officer died the next day, because we

lacked the tools to carry out amputations.

We believed that,

according to the custom of the country, their guns without mounts had

only one direction; but we were not a little surprised to see their

shots follow our movements, and force us to hasten our pace to occupy

the head of the village, and maintain the fight there, while the

riflemen and hunters had gone to turn their batteries and removed with

the bayonet. At the moment when the charge was being beaten, the

Mamluks rushed on our carabiniers, who received them with musketry fire

which turned them back; then, falling on the battery, they made a

general massacre of those who served it: the pieces were found to be

French, and it was recognized that they were those of Italy,

the flagship of our flotilla. We hoped that after this important

capture the fight would end with the dispersion or flight of the

Mekkain army; one part, however, still held out for quite a long time

in a small grove of palm trees, while the other, and the most

considerable, made a sort of retreat, which we could not (p.238)

disturb, because, every time if we went beyond the covered areas to

make a rapid movement, the Mamluks, whom we always had on our flank,

could attack us and overthrow us; it was therefore necessary to march

in battle order and always trained to receive them.

It had

already been six hours that we had been fighting relentlessly against

an inexperienced enemy, but brave, fanatical, and tenfold in number,

who attacked with fury and resisted with obstinacy: he only retreated

en masse; it was necessary to kill everything that had advanced in

detachments. Exhausted, panting from the heat, we stopped for a moment

to take breath: we were absolutely lacking in water, and we had never

needed it so much. I remember that at the height of the action I found

a jug at the corner of a wall, and that, not having time to drink,

while walking I poured the water into my breast. to quench the ardor

with which I was consumed.

As long as the enemy had his

batteries he fell back with confidence, because he fell back on new

forces: we even had to think that his design had been to attract us

towards them, but that after having lost them, the little wood where he

had retired becoming his last point of defense, he would try the fate

of a last fight, throw himself into the water, cross the Nile, or join

the Mamluks, and disappear with them; which it was impossible for us to

prevent: but, as we approached this wood, we noticed that it contained

a large village with a house of Mamluks, fortified, crenellated,

bastioned, and an approach all the more difficult that the enemy was

supplied with all kinds of arms and ammunition, which we recognized as

ours, both by the range of the rifles and by the bullets he sent at us.

We had already been attacking this house for more than two hours from

all sides, without finding one who was not murderous; we had lost sixty

men and had as many wounded: when night came, we set fire to the

adjacent houses, we captured a (p.239) mosque, we separated the enemy

from the Nile, and we worked to restore the parts taken back.

For

their part, the besieged were busy increasing the number of their

battlements, making low batteries, and aiming cannons which they had

not yet used. Peasants, who escaped from the fire of the besiegers and

that of the besieged, came to tell us that the day after the day of

General Desaix's departure to pursue Mourat, the Meccans, newly

descended from the desert, had come to attack Italy and the flotilla

she commanded; that after a fight of twenty-four hours, those who were

on board it broke out, and, fearing the collision, had burned the large

boat and mounted the small ones; but that a strong wind having

constantly thwarted their maneuver, tired by the number and the

relentlessness of the attackers, these unfortunate people had all been

killed; that since that time the Meccans had only thought of gathering

together all the means of attack and defense that this defeat provided

them with; that they had grounded one of our vessels, in order to force

everything that would sail on the river to pass under their battery,

and had thus made themselves masters of the Nile; that, despite all the

people they had lost, they were still very numerous and very determined.

At

daybreak, we began to batter the house: built of uncooked bricks, each

ball made no progress because of the courtyards which separated the

main building from the circumvallation. At nine o'clock in the morning,

the Mamluks advanced with camels as if to bring relief to the place; we

marched on them, and they withdrew without real resistance: General

Belliard, seeing that the conservative means were wearing out both men

and time, ordered an assault, which was given and received with

incredible valor; the first circumvallation was opened under enemy

fire, and, through the shootings and the exit of the besieged,

combustibles were introduced which began (p.240) to make their retreat

painful: one of their stores blew up; from then on the fire reached

them from all sides; they lacked water, they put out the fire with

their feet, with their hands, they smothered it with their bodies.

Black and naked, we saw them running through the flames; it was the

image of the devils in hell: I did not look at them without a feeling

of horror and admiration. There were moments of silence in which a

voice was heard; they responded to him with sacred hymns, with battle

cries; They then fell on us from all sides despite the certainty of

death.

Towards dusk an assault was made; it was long and

terrible; twice we entered the enclosure, twice we were forced to

leave: I was not so much upset by our losses as by the thought that we

would have to start new efforts against enemies who were ever more

reassured; I also knew that we were reduced to the last box of

cartridges. Captain Buliiot, an officer of distinguished bravery,

perished in the last attempt: this man, known for his reckless

imprudence, moved by a feeling of predestination, shook my hand as he

took me with him, and bade me a sinister farewell; the next moment I

saw him dragging himself on his hands, and trying to escape death.

When night came we stopped: we had been fighting for two days.

Danger

was followed by sad care; we heard the cries of our wounded, to whom we

had no remedies to give, to whom, for lack of instruments, we could not

carry out the most urgent operations; we had lost many people, and we

still had many enemies to defeat: the need to spare brave people led to

the reestablishment of fire in place of the assaults; fires were lit;

Posts were placed on all the avenues; or took turns to rest; the square

lay in battle; (p.241) danger dictated the accuracy of the service: in

the middle of the night, a donkey, chasing a donkey, galloped into the

neighborhood; everyone found themselves standing and at their post with

a silence and order as august that the cause was ridiculous.

An

unfortunate Coptic bishop, prisoner in the castle, under cover of

darkness escaped with a few companions, and only reached us through the

fire of our posts, covered with wounds and bruises: after having taken

some food, he told us the details of the horrors from which he had just

escaped. The besieged had had no water for twelve hours; their walls

glow; their thickened tongues choked them; Finally, their situation was

terrible. Indeed, a few moments later, an hour before daylight, thirty

of the best-armed besieged, with two camels, forced one of our posts

and passed through. At daybreak, we entered through the gaps in the

fire, and we finished knocking out those who, half burned, still put up

some resistance.

One was brought to the general; he appeared

to be one of the leaders; he was so swollen that when he bent down to

sit down, his skin burst all over: his first sentence was: If it is to

kill me that I am being brought here, let them hurry and put an end to

my pain. A slave had followed him; he looked at his master with such a

profound expression that it inspired in me esteem for both: the dangers

which surrounded him could not distract his sensitivity for a moment;

he only existed for his master; he looked, he saw only himself.

What

looks! what tender and deep melancholy! How good he must have been who

had made himself loved by his slave in this way! however dreadful his

fate was, I envied him: how loved he was! and I, looking back on

myself, said to myself: To satisfy a proud curiosity, here I am a

thousand leagues from my country; I accompany the brave, and I seek a

friend; while I grieve over the vanquished, over the victors, I see

(p.242) death striking around me; it is always his scythe that I

encounter everywhere: yesterday I was with warriors whose loyalty I

valued, whose brilliant bravery I admired; today I accompany their

convoy; tomorrow I will abandon their remains on a foreign land which

can only be disastrous for me: just now a young man, brilliant in

health and daring, braved the enemy he was going to fight; I see him

attack a deadly door, he falls; expressions of courage are followed by

accents of pain; he calls in vain; he drags himself, the fire reaches

him, communicates itself to the cartridges with which he is loaded; he

already has no form, and yet I still hear his voice; and tomorrow . . .

tomorrow his job will console the companion who will replace him for

his loss. O man, where will you draw virtues, if the noblest profession

still hides such small passions? Cruel selfishness, which misfortune

does not correct, and which becomes atrocious, because danger no longer

allows it to be hidden! it is in war that we can truly know it and

experience its terrible effects. But let’s turn our eyes to the

beautiful side of the profession.

Fig.5:

General Augustin Daniel Belliard (1769-1832) fought in the Battle of

the Pyramids, became governor of Upper Egypt, and advanced with his

troops into Nubia.

We

felt better than ever how useless it was to pursue them when they did

not want to fight, and the impossibility of surprising them in a

country where there remained for them on each side of the river a

retreat always open and always assured, as long as they would maintain

the superiority of the cavalry and that they would know how to protect

their camels. We therefore abandoned a useless pursuit, and wisely

returned to the guard of our boats: General Belliard spent the rest of

the day gathering and loading what we had captured of artillery,

ammunition and utensils of war.

It is after the attack that the

patient feels what strength the fever has taken from him. As long as we

had been fired upon with our powder and our cannonballs, we had not

calculated how much we would have to spend to exhaust or recapture that

which had been taken from us; but, calmer, we counted one hundred and

fifty men out of action, that is to say that we had played a lottery

where every seventh ticket was a red ticket, and that having made the

expenditure on ammunition on both sides, we barely had enough left to

provide for a fight; finally that the convoy which was to replace them

was destroyed along with all those who were supposed to defend it; that

we were a hundred and fifty leagues from Cairo where we were believed

to have no need. I had admired the quiet courage of General Belliard

during a fight of three days and two nights; I was no less edified by

his administrative intelligence in the hours which followed this

action, less brilliant than perilous: the slightest imprudence would

have added to the misfortune of having lost our fleet; disaster which

her prudent intelligence could not repair, but which at least she had

stopped what disastrous consequences the consequences of this loss

could have had.

(p.244) While we were dealing with the fate of

the inhabitants who had remained in Benhouth, and that of those who had

fled, I was not a little surprised to find in the posts we had in the

village all the established women with a cheerfulness and ease that

deceived me; I could not persuade them that they do not hear us. they

had each freely made their choice, and seemed very satisfied with it:

there were some lovely ones; it seemed so new to them to be fed, served

and well treated by victors, that I believe they would have willingly

followed the army. Belonging is so much their destiny that it was only

through the feeling of obedience that they returned to the power of

their fathers and their husbands; and, in these disastrous cases, they

are not received with that scrupulously inexorable jealousy which

characterizes the Orientals. It's war, they say, we couldn't defend

them; it is the law of the victors that they have suffered; they are no

more dishonored than we are by the wounds they have inflicted on us:

they return to the harem, and there is never any question of everything

that happened.

Through such delicate distinctions, does not

purified jealousy become a noble passion of which we can even be proud?

We learned that the sheikh who commanded or rather exhorted the

Mekkains had fled towards the end of the last night; that during the

siege he had prayed without fighting; that from time to time he came

out of his retirement and said to his people: I pray to heaven for you;

it's up to you to fight for him. It was after these exhortations that

we heard these pious chants, followed by war cries, sorties, and

general discharges.

Footnotes:

1. [Editor's note:] See also Chapter 37 of this volume, with two drawings by Denon of the main temple at Hermontis.

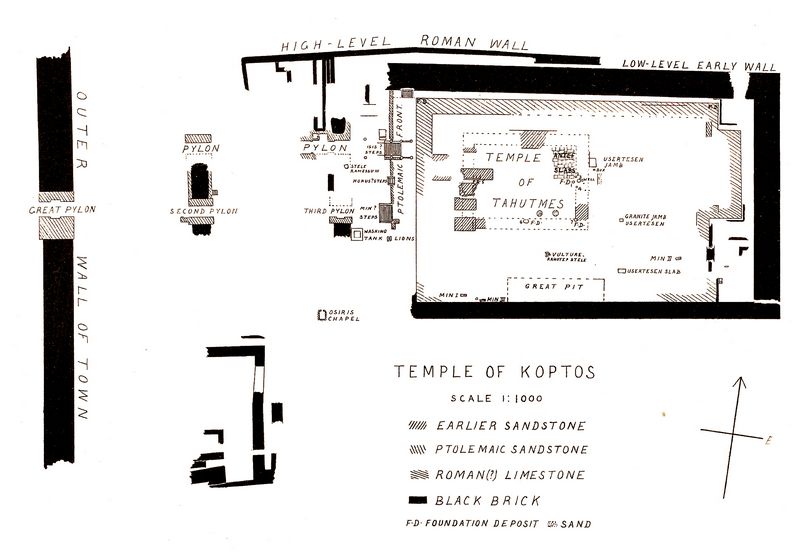

2.

[Editor's note:] Koptos was first excavated by W.M. Flinders

Petrie in 1893-4 . Earliest occupations date from the 4th Dynasty

of the Old Kingdom. Other structural remains date from the 18th

Dynasty of Thutmose III and Ramesses II of the 19th Dynasty. More

numerous are tombs and features from the Ptolemaic period including

a small granite temple from the reign of Ptolemy 13th Neos

Dionysos, the father of the famous Cleopatra VII. A nearby Roman temple

also lies in the village of Kaleh, less than a mile north of Kuft. For

more information, see Weigall, 1910, Antiquities of Upper Egypt; and Petrie and Hogarth, Koptos,

1896, Egypt Exploration Society, Quaritch, London. Recent surveys of

the site are being conducted by the Egypt Exploration Society and the

University of Lyon (see Pantalacci, L, and Gobeil, C. 2016. ‘Coptos:

the sacred precincts in Ptolemaic and Roman times’, Egyptian Archaeology 49).

.

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|