| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Voyage in Lower and Upper Egypt, during the Campaigns of General Bonaparte. Vivant Denon | | | | |

|

Chapter 33: Continuation of the March in Upper Egypt. - Fights with the Mamluks. - Thieves. - Arab storytellers. (p.165)

We

were waiting for the boats which were to follow our march, and which

were carrying our provisions, our ammunition, and the shoes of our

soldiers: the wind had always been favorable, unlike usual in this

season; and yet the boats did not arrive: we had sent various expresses

to obtain information; the first had perished while crossing the

revolted villages; the others no longer reappearing, our beautiful

season is lost in inaction; the country could believe that we were

afraid of the Mamluks, and this prejudice would once again mislead the

peasants: they already refused to pay the miri, and they said for

reason: There must be a battle; we will pay to the winner.

Fig.1, A (left): Detail of map of upper Egypt, with locations of sites named in the text,

(Denon

1802 vol.3, plate 1); B (right:)

Archaeological site map of the early 20th century, including

sites named by Denon (red dots)

(Atlas of the Egyptian

Exploration Fund, ca. 1910).

On

January 9 [1799], the tenth day of our arrival, General Desaix decided

(p.166) to send his cavalry to Siouth, to find out definitively what

had become of his maritime convoy; A battalion had been sent ahead of

Girgé to Bardis to look for provisions; the officer who commanded it

sent word to us, on the evening of the 9th, that it was rumored that on

the 11th the Mamluks would set out from Hau to arrive on the 12th, and

that they wanted to come to a battle: this news was confirmed on all

sides; and although Desaix was not convinced of this good fortune, he

still found himself in the position of reproaching our navy for

depriving him of our cavalry, which would leave him without the means

of profiting from the victory, if there was one; because the simple

infantry could only accept combat with the Mamluks, without ever

forcing them to do so or prolonging it.

Another

scourge that plagued us was perpetual theft, organized in such a way

that no military rigor could defend our weapons and our horses. Every

night the inhabitants entered our camps like rats, and left like bats,

almost always carrying off their prey. We had surprised some who had

been sacrificed at the first impulse of the soldier's rage: we hoped

that this rigor would cause some sensation; the guard was doubled; and

the same day two of the artillery forges were taken: the thieves were

seized, who were shot. During the night which followed this execution

the horses of the aide-de-camp of the general of the cavalry were

stolen: the general bet that no one would see him; The next day his

horse was taken from him, and a wall was demolished to surprise him

himself, if daylight had not come to his aid.

On the 10th, we

learned that Mourat-bey invited the Arab sheikhs of the subject

villages to march against us, giving them an appointment at Girgé. On

the 11th, the day he saw us attack, several sent us their letters,

(p.167 ) by telling us that they remained faithful to the treaty, and

denounced those who had promised to march; but the encounter they saw

with our cavalry had disconcerted their plans. On the 11th, the weather

was overcast, and we suffered from it like a rather harsh winter's day,

although it was one of our very beautiful April days; so true is it

that the absence of the good on which we have counted is already an

evil! I live, however, in this terrible day. a green vine trellis like

in July; the leaves here only harden, turn red, and dry, while the tip

of the branch perpetually renews its greenery; climbing peas do the

same thing; the stem becomes woody: I have seen some that were forty

feet high, and reached the top of trees.

We knew that an

innumerable number of infantrymen had arrived from Mecca via Cosseïr to

join Mourat-bey, and that they were on the march to attack us.

On

the 13th, we learned that our cavalry had encountered a gathering at

Menshieth, had cut down a thousand of these strays, and had continued

on its way; a lesson that was nothing less than fraternal, but which

our position perhaps made necessary: this province, which, always in

revolt, had the reputation of being terrible, needed to learn that it

was not when it measured itself against us ; we also had to hide from

them that our means were small and scattered; perhaps they still had to

believe us to be as vindictive as we were clement; perhaps finally, not

having time to catechize them, it was necessary, through an unfortunate

circumstance, to severely punish those who persisted in doing so. not

believing that everything we did was only for their good.

We

were preparing to leave as soon as the cavalry returned, whether the

boats finally arrived or it was necessary to abandon them; because

(p.168) waiting only aggravated our troubles, and those that we were

obliged to inflict on the inhabitants of the surrounding area, by

allowing this state of war, uncertainty, and disorganization to persist.

On

the 14th, we had no news yet. We had Arab tales recited to us to kill

time and temper our impatience. The Arabs tell stories slowly, and we

had interpreters who could follow or who slowed down the flow very

little: they preserved the same passion for the tales that we have

known in them since Sultan Sheherasade of The Thousand and One Nights;

and on this article Desaix and I were almost sultans: his prodigious

memory did not lose a sentence of what he had heard; and I wrote

nothing of these tales, because he promised to give them back to me

word for word whenever I wanted: but what I observed was that if the

stories were not rich in true and sentimental details, a merit which

seems to belong particularly to the narrators of the north, they abound

in extraordinary events, in strong situations, produced by passions

always exalted; kidnappings, castles, gates, poisons, daggers,

nocturnal scenes, misunderstandings, betrayals, everything that

confuses a story, and seems to make its outcome impossible, is used by

these storytellers with the greatest boldness; and yet the story always

ends very naturally and in the clearest and most satisfying manner.

This

is the merit of the inventor: the storyteller still has that of

precision and declamation, to which the listeners place a lot of value:

it also happens that the same story is told consecutively by several

narrators in front of the same listeners , with equal interest and

equal success; one will have better treated and declaimed the sensitive

and loving part, another will have better rendered the fights and the

terrible effects, a third will have made people laugh; finally it is

their show: and as with us we go (p.169) to the theater once for the

play, other times for the acting, the rehearsals do not tire them at

all. These stories are followed by discussions; applause is contested,

and talents are perfected; also there are some of great reputation who

are cherished, and bring happiness to a family, to a whole horde. The

Arabs also have their poets, even their improvisers, who are brought to

the feasts; they seem enchanted by it: I have heard them; but when

their songs are not apologetic, they undoubtedly lose too much in being

translated; they only seemed to me to be rather insipid concetti or

puns: their poets also have extraordinary manners, tics, which set them

apart in the eyes of the locals, but which gave them an air of madness

for us which inspired me with pity and repugnance: it was not the same

with the storytellers, who seemed to me to have a truer talent, closer

to nature.

I must have been less distressed than others by the

delays, since they gave me time to calm the inflammation that was

devouring my eyes; but I shared the impatience of Desaix, who had had

to count on all the resources of the convoy, the absence of which

paralyzed its operations in all respects, and left it in distressing

destitution: fortunately the sick and wounded were few in number;

because doctors without remedies were only there to tell them which

ones should have been given to them, and could not administer any to

them; However, we had a hospital, ovens, a store established, and a

barracks well fortified enough to defend against a riot or an attack by

peasants, and to be able to leave three hundred men in this level of

security at this scale of the Nile.

Not knowing what to do with

my sick eyes, I thought of going to the local baths, which relieved me.

I refer my reader to the elegant description of Mr. Savary, whose

laughing imagination has created both (p.170) the picture of the

pleasures that these baths offer, and the pleasures of which they are

capable.

On the 15th, it was cold enough in the morning to want

to warm up; but this cold nevertheless resembles that which we

sometimes experience at home in the month of May; because when I put my

head to the window, I saw the birds making love, or at least making

their nest to do so: in the evening of the same day it thundered, a

very extraordinary event in this country; in fact this only happens

once in a generation, through a combination of circumstances perhaps

easy to explain. The north wind, the most constant of all those which

dominate in this part of the world, brings the clouds from the sea from

a colder region, rolls them into the valley of Egypt, where the fiery

ground rarefies them, and reduces them to vapor; this vapor pushed as

far as Abyssinia, the south wind, which crosses the high and cold

mountains of this country, sometimes brings back small clouds, which,

experiencing only a slight change in temperature as they pass back

through the humid valley of Nile when it overflows, remain condensed,

and sometimes produce, without thunder or storm, small rains of an

instant; but the east and west winds, which usually give birth to

storms, both cross fiery deserts which devour the clouds, or raise the

vapors to such a height that they cross the narrow valley of Upper

Egypt , without being able to experience a detonation by the impression

of the waters of the river, the phenomenon of thunder becomes a thing

so strange for the inhabitants of these regions, that even the

scientists of the country do not imagine attributing a physical cause

to it.

General Desaix questioned a lawyer about thunder, he

replied with the security of assurance: "We know very well that it is

an angel, but it is so small that we do not see it in the air; however,

he has the power to bring the clouds of the Mediterranean to Abyssinia;

and, when the wickedness of men (p.171) reaches its height, he makes

his voice heard, which is that of reproach and threat; and, as proof

that punishment is at his disposal, he half-opens the door of heaven,

from which comes lightning; but, the clemency of God being always

infinite, never in Upper Egypt did his anger otherwise manifested." We

are always amazed to hear a sensible man, with a venerable beard, tell

such a childish tale. Desaix wanted to explain this phenomenon to him

differently; but he found her explanation so inferior to his own, that

he did not even take the trouble to listen to it: besides, it had

rained all night; which made the streets muddy, slippery, and almost

impassable. Here ends the story of our winter, and I will not have to

speak of it any more.

On the 15th, ovens were made for the use

of the country. On the 16th, we made biscuits. I would have liked in my

drawing to be able to express the skill and speed of the workers; we

can say that individually the Egyptian is industrious and skillful, and

that lacking, like the savage, any kind of instrument, we must be

surprised at what they do with their fingers to which they are reduced

, and with their feet, which they use wonderfully: they have, as

workers, a great quality, that of being without presumption, patient,

and of starting again until they have done approximately this that you

want from them. I don't know to what extent we could make them brave;

but we must not see without fear all the qualities of soldiers that

they possess; eminently sober, pedestrians like runners, squires like

centaurs, swimmers like mermen; and yet it was over a population of

several million individuals who possessed these qualities that four

thousand isolated French people imperiously commanded over two hundred

leagues of country; so much so that the habit of obeying is a way of

being like that of commanding, until some fall asleep in the abuse of

power, others are awakened by the sound of their chain!

On the

18th, the cavalry returned; she announced to us the arrival of the

boats, and (p.172) gave us the details of a fight she had had to wage

against some Mamluks and their agents, who had spread the rumor that

they had destroyed us; that what we saw falling back was the rest of

the French who were trying to reach Cairo. Two thousand Arabs on

horseback, and five to six thousand peasants on foot, thought they had

overcome it; they had gone in front of Tata; when the cavalry

discovered them in battle, they had moved to form; they had believed

that she was declining the fight, and had charged with the usual

disorder, that is to say a few brave men in front, the rest in the

middle, always striking and never parrying; at the second discharge,

surprised to see the cavalry firing battalion fire, they had begun to

give up; and, after having lost forty of their number, and having had a

hundred wounded, they had disappeared, dispersing, and abandoning the

poor infantry, which as usual, had been chopped up, and would have been

destroyed, had it not been for night. came to his aid.

On the

20th, the boats finally arrived; some conveniences that they brought

us, and above all the music of one of our demi-brigades playing French

airs, created such a strangely voluptuous sensation for Gir-gé, that it

calmed everything that impatience had caused. irascibility in our mind.

It was, alas! the swan song: but let's not anticipate events: in war

you have to enjoy the moment, since the one that follows belongs to no

one.

On the 21st, the loan, the brandy, revived our existence;

and the soldier, already tired of eating six eggs for a penny, set off

with joy to meet the need.

For twenty-one days we had only been

tired of our worthlessness: I knew that I was near Abidus, where

Ossimandué had built a temple, where Memnon had resided [1]; I

tormented Desaix to carry out reconnaissance as far as El-Araba, where

every day I was told that there were ruins; and every day Desaix said

to me: I want to take you there myself; (p.173) Mourat-bey is two days

away, he will arrive the day after tomorrow, there will be a battle, we

will defeat his army, the other day after tomorrow we will only think

about antiquities, and I will help you myself- even in measuring them,

the good Desaix was right; and if his reason had not been good, I would

have had to put up with it.

Finally on the 22nd, we left Girgé

at the onset of night; we passed opposite the antiquities; Desaix did

not dare look at me; Tremble, I said to him; If I am killed tomorrow,

my shadow will pursue you, and you will constantly hear it around you

saying, El-Araba. He remembered my threat, because five months later he

sent an order from Siouth to give me a detachment to accompany me there.

We

arrived in front of a village; we didn't know until the next day that

it was called El-Besera, because in the evening there was not a

resident to tell us: I quite liked finding the villages moved, so as

not to hear the cries of the inhabitants that we were forced to strip;

only walls remained in the planned moves; the doors and even the

doorframes were swept away, and a village abandoned for two hours had

the appearance of being a century-old ruin.

On the 23rd, barely

on the march, like the most idle person, I was the first to see the

Mamluks; they marched towards us on a front of immense extent: we

formed ourselves into three squares, two of infantry on the wings, and

one of cavalry in the center, flanked by eight pieces of artillery at

the corners; we marched in this order, following our route up to a

quarter of a league from Samanhout, an elevated village, against which

we sought to support ourselves. The Mamluks expanding and turning us on

three points, they began their firing and their shouts before we

thought of firing the cannon. A body of volunteers from Mecca was

stationed in a ravine, between the village and us, and fired under

cover on the square (p.174) the twenty-first: Desaix sent a detachment

of infantry to dislodge them from the pit , and a detachment of

cavalry, which was to pursue them when they were driven out. The

cavalry, too ardent, attacked too early and with disadvantage; one of

ours was killed, another was wounded; aide-de-camp Rapp received a

saber blow, and would have died, if a volunteer had not warded off four

other blows with which he was threatened; the Meccans were, however,

repulsed.

Chasseurs were sent to the village to dislodge those

who occupied it; the Mamluks moved to attack our left, while others

skirted our right: they had a favorable moment to charge us; they

hesitated, and found him no more; they pranced around us, flashing

their resplendent weapons and maneuvering their horses; they displayed

all the oriental splendor: but our northern austerity presented a

severe aspect which was no less imposing; the contrast was striking,

the iron seemed to defy the gold; the plain sparkled, the spectacle was

admirable. Our artillery fired on all sides at once: they made a false

attack on our right; several of their number perished there; a leader,

hit by a cannonball, was. fell too close to us to be rescued by his own

people; his horse, surprised to see him dragging himself, without

abandoning him, would not let himself approach; all shining with gold,

it excited the greed of the riflemen, who tried at every moment to make

it their prey; struggling with fate, dragged here and there by his

horse, this unfortunate man only perished after having suffered the

horrors of a thousand deaths.

Other chasseurs had been sent to

Samanhout to dislodge those who had stationed themselves there; they

soon put them to flight: among these fugitives was Mourat, who had put

himself in reserve there; he took the road to Farshiut. This movement

divided the entire enemy army: Desaix seized this circumstance, marched

on the space it was abandoning, and ordered (p.175) the cavalry to

charge those who still remained on our right; in an instant, we saw

them in the desert climbing a first slope of the mountain with

surprising speed: we thought that once they arrived on the plateau they

would prevent our people from approaching it; but terror and disorder

were in their ranks, they only thought of reuniting in their flight;

some stragglers were killed, some camels were taken; a small separate

body fled to the left: the fire ended at noon, at one o'clock we saw no

more enemies. We marched to Farshiut, which Mouratbey had already seen

abandoned.

This unfortunate town had been pillaged a few hours

earlier by the Mamluks. The sheikh was a descendant of the Àramam

sheikhs, powerful and beloved sovereigns in the Said, who, at the

beginning of this century, had reigned with equity, and defended their

subjects from the vexations of the Mamluks. The latter, beaten by

Mourat, reduced to a state of weakness and misery, had seen with

pleasure the avengers arriving, and had prepared biscuits for them:

Mourat, beaten, forced to flee, before leaving Farshiut sent for this

old prince, overwhelms him with reproaches, and in his fury cuts off

his head with his hand. We arrive, we finish looting the stores; the

general is defeated to prevent this disorder; it would have been

necessary to punish the whole army: a forced march would have been

ordered; and, to avoid the reproachful looks of the inhabitants, we

leave at midnight.

The darkness was terrible, and the cold was

severe enough to force us to light fires every time the artillery

stopped us; sheltered against the wall of a house near one of these

fires, we were warming ourselves, Desaix, his aides-de-camp, and I,

when suddenly we received a shooting over the wall: they were still

volunteers from Mecca, because we were destined to meet them

everywhere; there were twenty of them, eight were killed; the others

fled under cover of darkness. These volunteers, who (p.176) claimed to

be noble, wore a green turban, as descendants of the race of Hali;

these knights, almost vagabonds, robbing the caravans on the coast of

Gidda, and driven by great zeal, took advantage of the dead season to

come and attack a European nation that they believed to be covered in

gold, and saw willing to come at their own risk and fortune to forage

on us.

Armed with three javelins, a pike, a dagger, two pistols

and a carbine, they attacked with audacity, resisted with obstinacy;

and, although mortally struck, seemed unable to stop living: during

this last surprise, I saw one of them fight again, and wound two of

ours who had him pinned against a wall with their bayonets. We arrived

at one hour of sunlight in Haw; the Mamluks had just left there: some

of the beys had entered the desert with the camels to arrive by this

route in a day and a half at Esneh; the others had followed the Nile, a

route by which there are four. Haw, or ancient Diospolis-Parva, is in a

fine military position: it preserves no antiquities [2].

We

stopped at Haw, and left there an hour before nightfall, which, as we

had learned the day before, would be dark and make the march of our

artillery perilous. But the conquest of Egypt, which had been begun so

brilliantly by the battle of the pyramids, would have ended in the same

way with the battle of Thebes, if it had been possible to obtain it

from our Fabius Mourat-bey. How many forced marches the dream of this

battle cost us! but Desaix was not the spoiled child of fortune, and

his star was nebulous: experience could not convince him of our

insufficiency to overtake the enemy we were pursuing by speed; he did

not want to hear anything that could weaken his hopes. The artillery

was too heavy, the infantry too slow, the large cavalry too heavy; the

light cavalry (p.177) would hardly have supported his will; and I am

sure that he groaned at not being a simple captain, to go, in his

boiling ardor, with his company to attack and fight Monrat-bey: finally

we left, and, after being illuminated by the false glow of an aurora

borealis, and having waited for the moon until half past ten, we

arrived at eleven o'clock at a large village, whose name I never knew,

and where, fortunately for it and to the great prejudice of its

inhabitants , our soldiers lost their way...

On the 25th, we

left at first light. The tongue of cultivated land gradually narrowed

on the left bank where we were, and increased in the same proportion on

the other bank.

Finally we entered the desert; We saw there

quite closely a wild beast, which from its size and remarkable shape we

all judged to be a hyena; we ran over it, but the gallop of our horses

could only follow it without gaining anything on it. We were

approaching Tintyra: I dared to speak of a halt; but the hero answered

me angrily: this disfavor only lasted a moment; soon, recalled to his

sensitive nature, he came to seek me out, and sharing my love for the

arts, he showed himself to be their friend, and perhaps more ardent

than me. Endowed with a truly extraordinary delicacy of mind, he had

united the love of everything that is amiable with a violent passion

for glory, and with a number of acquired knowledge, the means and the

will to add to those which he had not had time to perfect it; we found

in him an active curiosity which made his society always pleasant, his

conversation continually interesting.

Chapter 34: Tintyra [Dendera] [3] (p.178)

We

arrived at Tintyra: the first object I saw was a small temple on the

left of the path, of such bad style and in such bad proportions, that I

judged it from a distance to be only the ruins of a mosque. Turning to

the right, I found buried in the saddest rubble a constructed waste of

enormous masses covered with hieroglyphics; through this door I saw the

temple. I would like to be able to convey to the souls of my readers

the feeling I experienced. I was too surprised to judge; all that I had

seen until then in architecture could not serve to regulate my

admiration here. This monument seemed to me to have a primitive

character, to have that of a temple par excellence. Crowded as he was,

the feeling of silent respect he gave me seemed proof of it; and,

without partiality for the ancient, it was the one he imposed on the

whole army.

Before going into any detail, let us try to show

through the plans and views the extent and layout of this building, its

current state, and its picturesque effect (plates 13-15, and 47-49). I

have tried through my drawings to give a general idea of the situation

of the ancient city, the location it occupied, and the respective

location of the buildings, their current state, and the richness of

their details. These monuments were located on the edge of the desert,

on the last plateau of the Libyan chain at the foot of which the river

floods, a league from its bed.

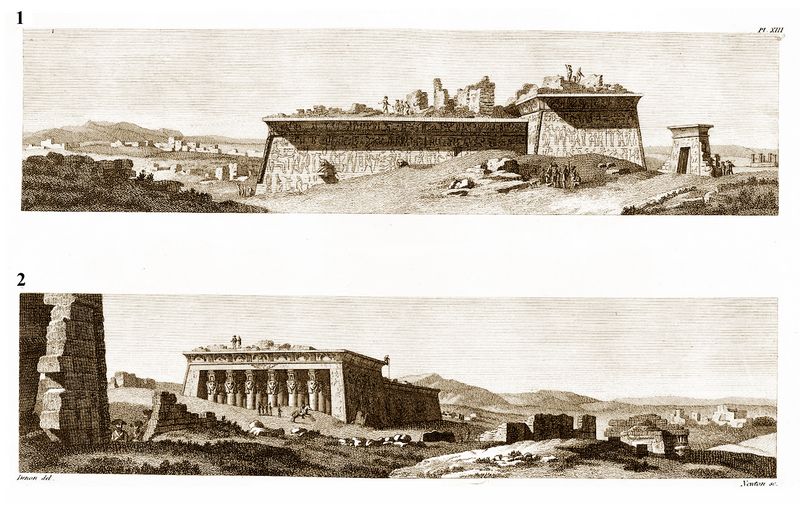

Plate 13: Views of the temple of Tentyris [Dendera].

"No.

1.—A view of the southern part of the great temple of Tentyris; on the

right, in the distance, a small monument, which is opposite the large

door, against which the enclosure which closed the temple undoubtedly

leaned: this door opens opposite the center of the portico; it is

covered with hieroglyphics inside and out. "

"No. 2.—The portico

of the temple facing east; on the left, a fragment of the door; on the

right, a small temple; in the background, the Libyque chain, west of

the city."

"The portico is higher than the one or nave; an

austere simplicity in the architecture is enriched by an innumerable

quantity of hieroglyphic sculptures, which however do not disturb the

beautiful lines: a large cornice majestically crowns the entire

building; a twist, which seems to encircle it, adds yet another aspect

of solidity to the embankment which exists everywhere, and serves as an

impasto, and which removes the thinness of the repeated angles, without

removing the precision and firmness of the whole, since this firmness

manifests itself where it should be pronounced, that is to say at the

end of the cornices."

"Three sphinx heads emerge from the side

of the one or nave; from their shape and the gutter which is between

their paws we must believe that they were gutters through which the

water would have flowed which would have been poured onto the platform

of the temple to cool the buildings which were built there, because

under the ruins of the Arab constructions which we still see on this

monument, I found small particular temples, decorated with the most

careful and scientific sculptures: it was in one of these apartments

that I saw and drew the zodiac, and other interesting details, which I

will explain in the hieroglyphs article."

"Nothing could be

simpler and better calculated than the few lines that make up this

architecture. The Egyptians having borrowed nothing from others, they

added no foreign ornament, no superfluity to what (p.179) was dictated

by necessity: order and simplicity were their principles; and they

raised these principles to sublimity: having reached this point, they

placed such importance on not altering it, that, although they

overloaded their buildings with bas-reliefs, inscriptions, historical

and scientific paintings, none of these riches intersect a single line;

they are respected; they seem sacred; all that is ornament, wealth,

sumptuousness up close, disappears from afar to reveal only the

principle, which is always great and always dictated by a powerful

reason."

"The modern dwellings, of which we can still see the

ruins, will undoubtedly have been built at this elevation with the idea

of sheltering themselves from the incursions of the Bedouins, and of

lodging themselves on these monuments as in a fortress, or else to move

away from the fiery ground, and seek air in a higher region. The rest

of what this print presents is nothing more than rubble, and torn

pieces of

factory walls, the last built with materials from the

ancient city, which, with the exception of the temples, was built of

bricks. The quantity of Roman coinage from the time of Constantine and

Theodosius, which we find every day when digging for nitre, must make

us believe that Tintyra still existed at that time: I myself found

Roman lamps there in terracotta, mixed in the rubble with small

Egyptian deities in glass paste and porcelain, with a blue cover." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Plate 14: View of portico of the temple of Tentyris [Dendera].

"Geometric

view of the portico of the great temple: on the plinth of the cornice

we see a Greek inscription, too high and too crude for my eyesight to

have allowed me to copy it; I believe it to be a dedication made

subsequently by some governors of the province for the Ptolomecs:

another Greek inscription, similarly placed on the south door, and

which I copied exactly, could support this opinion; in the middle of

the cornice is in relief a head of Isis [4] repeated everywhere: it shows

that the temple was dedicated to this divinity; below, on the

entablature, is the winged globe which occupies this place in all

buildings; this same figure is repeated here on all the stones in

flower beds which form the ceiling of the intercolumnation in the

middle of the portico."

"The capitals of the columns, very

extraordinary for the ornament which decorates them, produce in the

execution an effect as noble as it is rich. The door was formed of two

jambs without cymas; the seat supporting the hinges was made of

granite; which could lead one to suspect that this part of the lintel

exposed the friction of the hinge; the choice of this harder material

announcing that the socket of the hinge was not made of bronze or iron,

but that the wooden hinge rolled in the socket of the stone itself. The

part which engages the columns is buried; I was unable to see the

ornaments, never having had the time to have them excavated; I

supplemented this with those that I found on the same member of

architecture at the open temple of Philae." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Plate 15: View of interior door at Tentyris [Dendera].

"Interior

door of the temple sanctuary (See the plan, fig. 7, Plate XLVII). I

carefully measured all the parts of this superb fragment of Egyptian

architecture; I placed the different kinds of hieroglyphs there with

accuracy: I expressed the perfect conservation of this part of the

building; which means that the image I give becomes both a geometric

view and a picturesque view. Plan No. 2, which I added at the bottom,

will give the measurement of the projection of the different members of

this piece of architecture." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

"No.

5 is the plan of a temple dedicated to Typhon, judging by the ornaments

of the friezes, where this evil genius is always in attitude

of adoration before the goddess Isis."

"No. 6 is the plan of an open temple, which was never completed.

"No.

7, the plan of the great temple and its portico, supported by

twenty-four columns similar to those No. 1; the sculpted and painted

ceilings are the planisphere and the zodiac of Plate XLVIII, and of

Plate XLIX. The room which follows, supported by six columns, is very

buried, and receives daylight only from the door; the capitals of the

columns which support the ceilings of this room are composed of the

capital of the column of the portico; plus a flared capital, like that

Plate XLV, No. 7; I was unable to judge the rest of the column."

The

room which follows, much cleared away, is very dark; the one beyond,

very decorated, received a little light from drip edges located near

the ceiling; the light is represented in sculpture, under the recess of

the drip edge, by triangular drops which always chase each other and

enlarge; the entire back side of this room is decorated with the

beautiful door, a view of which I give on Plate XV, nothing indicates

what its use was. The back room was undoubtedly the sanctuary; it only

received daylight and air from the door, which opened onto a room that

was already very dark: if any functions took place in the interior of

these temples, it must have been at night, because if the religious

ceremonies were not Had it only taken place outside, what was the point

of the extreme magnificence of the details of the interior decoration?

the sanctuary, absolutely cleared, was excavated down to the ground of

its pavement, which rested on the flattened rock; this room was

isolated, like all sanctuaries - Without having been able to penetrate

into the space between the back wall and that of the exterior of the

temple, I was able, by comparing the interior and exterior measurements

, judge its space:

"all the parts of the plan which are shaded

are too cluttered rooms which I could not enter; one of the three side

rooms contains a landing staircase, the steps of which are only four

inches high, and which rises onto the terrace of the nave of the

temple, from where another side staircase still ascends to the lowest

platform. highest of the portico: the sculptures of these stairs are as

numerous and as careful as those of the sanctuary; those on the

staircase are mostly figures of priests and soldiers presenting

offerings. Along the steps that ascended to the peristyle platform were

fourteen deities on fourteen steps. At the outer part of the back of

the temple there is a head of Isis, similar to that of the peristyle

cornice, but in colossal dimensions, to which on each side two gigantic

figures sculpted in bas-relief present incense." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Plate 47: Details of the Temple of Tentyris.

"No.

1 is a perspective view of a column isolated from the peristyle of the

great temple; the square part of the capital represents a temple with

the divinity under the portico of the sanctuary; four faces of Isis

[4], with cow's ears, and the hairstyle of Egyptian women complete this

capital; all the ornaments which cover the shaft are accurate, as well

as the base of the column, which I had excavated to find out."

"No. 2, the capital upside down, seen in plan."

"No. 3, with the bust of a lion, is one of the gutters which decorate the sides of the nave."

(Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Nothing

could be simpler and better calculated than the few lines that make up

this architecture. The Egyptians having borrowed nothing from others,

they added no foreign ornament, no superfluity to what (p.179) was

dictated by necessity: order and simplicity were their principles; and

they raised these principles to sublimity: having reached this point,

they placed such importance on not altering it, that, although they

overloaded their buildings with bas-reliefs, inscriptions, historical

and scientific paintings, none of these riches intersect a single line;

they are respected; they seem sacred; all that is ornament, wealth,

sumptuousness up close, disappears from afar to reveal only the

principle, which is always great and always dictated by a powerful

reason.

Plate 48: Planisphere of the small Apartment of the Temple of Tentyris.

"Planisphere

carved on the ceiling of the small apartment which is on the roof of

the great temple of Tintyra: it is very difficult to say what was the

use of this small apartment: was it an oratory, an observatory, a

sanctuary, an apartment ? judging by the subjects sculpted there, one

could believe that it was a place of study, a place devoted to

astronomy, or perhaps entirely devoted to the burial of a commendable

character who would have discoveries recorded there, the result of his

life's studies

"When I drew this

planisphere, I did not hope to give an explanation, but to provide

proof that the Egyptians had a planetary system, that their knowledge

of the sky was reduced to principles, that the only image of their

signs obviously proved that the Greeks had taken these signs from them,

and that through the Romans they had reached us; I finally thought I

was in a position to offer the scholars and antiquaries of Europe a

tribute worthy of them, and to deserve their recognition." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Plate 49: Zodiac from the Ceiling of the Portico of the Temple of Tentyris.

"The

two parts of a zodiac on the two most opposite flowerbeds of the

ceiling of the portico of the temple of Tintyra, the two large

enveloping figures appear to be those of the year. The winged sign

which is in front of their mouth is that of eternity or the passage of

the sun at the solstices: the disc which is at the joint of the thighs

of figure No. 1, the sun, from which a beam of light comes which falls

on a head of Isis, which represents either the earth or the moon; the

sun, placed in the sign of Cancer, can serve as a time for the erection

of the temple: the figures joined to the signs, the fixed stars; those

in boats, moving stars, planets, and comets. The more important the

objects of these paintings are, the more they seem to me to have to be

left to the scholars to whom they belong; my observations must focus

more particularly on small isolated objects, to which the localities,

the connections, the circumstances, give interest, and to which the

details of my observations can sometimes give existence."

"These

large flower beds are sculpted and painted; the characters in natural

colors on a blue background strewn with yellow stars: I have only

marked those which are in relief, the others being indefinite in

number, and having disappeared for the most part through degradation.

The inscriptions are correct; I marked with small lines the places

where the degradation did not allow me to distinguish the figures; a

large shard of stone which fell carried away several of the second

band." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

It doesn't rain in this climate; so only flower beds

were needed to cover and provide shade; henceforth no more roofs,

henceforth no more pediments: the embankment is the principle of

solidity; they adopted it for everything that carries, no doubt

believing that confidence is the first feeling that architecture must

inspire, and that it is a constituent beauty. Among them the idea of

the immortality of God is presented by the eternity of his temple;

their ornaments, always reasoned, always in agreement, always

significant, also prove sure principles, a taste founded on truth, a

profound series of reasonings; and if we had not acquired the

conviction of the eminent degree to which they had reached in the

abstract sciences, their architecture alone, in the state in which we

found it, would have given us the idea of the antiquity of this people

, its culture, its character, its seriousness.

I would have no

expression, as I said, to express all that I felt when I was under the

portico of Tintyra; I believed I was, I really was, in the sanctuary of

the arts and sciences. How many eras presented themselves to my

imagination, at the sight of such a building! how many centuries it

took to bring a creative nation to such results, to this degree of

perfection and sublimity in the arts! how many more centuries to

produce the forgetting of so many things, and to bring man back on the

same soil to the state of nature in which we found him! never so much

space in a (p.180) single point; never have the steps of time been more

pronounced and better followed. What constant power, what wealth, what

abundance, what superfluity of means in the government which can raise

such an edifice, and which finds in the nation men capable of designing

it, of executing it, of decorating it, of enrich with everything that

speaks to the eyes and the mind! never in a closer manner had the work

of men presented them to me so ancient and so great: in the ruins of

Tintyra. the Egyptians seemed giants to me.

I would have liked

to draw everything, and I dared not put my hand to the work; I realized

that, not being able to rise to the height of what I admired, I was

going to diminish what I would like to imitate; nowhere had I been

surrounded by so many objects capable of exalting my imagination. These

monuments which impressed the respect due to the sanctuary of the

divinity, were the open books where science was developed, where

morality was dictated, where useful arts were professed; every parlor,

everything was lively, and always in the same spirit. The doorways, the

corners, the most secret way back, still presented a lesson, a precept,

and all this in admirable harmony; the lightest ornament on the most

serious member of architecture displayed in a living manner the most

abstract thing that astronomy had to express. Painting added further

charm to sculpture and architecture, and produced at the same time a

pleasant richness, which detracted neither from the simplicity nor the

gravity of the whole.

Painting in Egypt was still just another

ornament; to all appearances, it was not a particular art: the

sculpture was emblematic, and, so to speak, architectural. Architecture

was therefore the art par excellence, dictated by utility; it could

therefore alone raise the doubt, if not on primogeniture, at least on

the superiority of the architecture of the Egyptians compared to that

of the Indians, since not participating in any way in that of the

latter, it has become the principle of all this which (p.181) we have

since admired, of all that we believed to be exclusively architecture,

the three Greek orders, the Doric, the Ionic, and the Corinthian. We

must therefore be careful not to think, as we wrongly believe, that

Egyptian architecture is the childhood of art, but it must be said that

it is its type.

I was struck by the beauty of the door which

closed the sanctuary of temple (plate 15); all that architecture has

since added ornaments to this type of decoration has only reduced its

style.

I should not hope to find anything in Egypt more

complete, more perfect than Tintyra; I was agitated by the multiplicity

of objects, amazed by their novelty, tormented by the fear of not

seeing them again. I had noticed on ceilings planetary systems,

zodiacs, celestial planispheres, presented in a tasteful arrangement; I

had seen that the walls were covered with the representation of the

rites of their worship, of their procedures in agriculture and the

arts, of their moral and religious precepts; that the Supreme Being,

the first principle, was everywhere represented by the emblems of his

qualities: everything was equally important to bring together; and I

only had a few hours to observe, to think, to draw what had cost

centuries to design, to build, to decorate. Our impatience Françoise

was appalled by the constant will of the people who had executed these

monuments: everywhere the same equality of research and care; which

could make one think that these buildings were not the work of kings,

but that they were built at the expense of the nation, under the

direction of colleges of priests, and by artists to whom invariable

rules were imposed.

A period of time could have brought them

some perfections in art; but each temple is of such equality in all its

parts, that they all seem to have been sculpted by the same hand;

nothing better, nothing worse; (p.182) no negligence, no impulses apart

from a more distinguished genius; wholeness and harmony reign

everywhere. The art of sculpture, linked to architecture, was

circumscribed in principle, in method, in mode: a figure expressed

nothing through feeling; she had to have a certain pose to mean a

certain thing; the sculptor had the cliché, and should not allow

himself any alteration which could have changed its true meaning: these

figures were like our playing cards, of which we respected the

imperfections, so as not to take away anything from the ease. with

which we know how to recognize them. The perfection that they gave to

their animals proves enough that they had the idea of style, the

character of which they indicated with so few lines in such a great

principle, and a system which tended towards the serious and the

beautiful ideal. , as we already had proof in the two sphinxes of the

capitol, and whose style we find here in those which are on the side of

the great temple.

As for the character of their human figure,

borrowing nothing from other nations, they copied their own nature,

which was more graceful than beautiful. That of the women still

resembles the face of the pretty women of today: roundness,

voluptuousness; the nose is small; the eyes are long, not very open,

and raised to the exterior angle, like all people whose organ is tired

by the heat of the sun or the whiteness of the snow; the slightly thick

cheekbones, the lined lips, the large, but smiling and graceful mouth:

in all, the African character, of which the Negro is the charge, and

perhaps the principle.

The hieroglyphs, executed in three ways,

are also of three genres, and can also have three periods: by examining

the different buildings that I was able to observe, I was able to judge

that those which must be the oldest have only a simple outline, dug

without relief, and very deeply; the second, those which have the least

effect, are simply (p.183) in very low relief; and the third, which

appear to me to be of the best time, and which are in Tintyra of a more

perfect execution than in any other place in Egypt, are in relief at

the bottom of the hollowed outline, Through the figures which make up

the paintings , there are small hieroglyphs, which appear to be only

the explanation of the tables, and which, with simplified forms, would

seem a quicker way of expressing oneself, a kind of cursive writing, if

one can say so. say this when speaking of sculpture.

A fourth

genre seemed to be devoted to ornament; we have called it incorrectly,

and I do not know why, Arabesque: adopted by the Greeks, at the time of

Augustus it was admitted among the Romans, and in the fifteenth

century, during the renaissance of the arts, it was transmitted to us

by them as a fantastic decoration, of which the taste was all the merit.

I

had just discovered a celestial planisphere in a small apartment (plate

48), when the last rays of the day made me realize that I was alone

with the constantly kind and obliging General Belliard, who, after

having seen it for himself, did not want to see me abandoned in such a

deserted place. (p.184)

We galloped over the division, already

at Dindera, three quarters of a league from Tintyra, where we came to

sleep: without orders given, without orders received, each officer,

each soldier had turned away from the road, had rushed to Tintyra, and

spontaneously the army remained there the rest of the day. What a day !

How happy we are to have defied everything to obtain such pleasures!

In

the evening, Latournerie, an officer of brilliant courage, wit and

delicate taste, came to find me, and said to me: "Since I was in Egypt,

deceived about everything, I have always been melancholy and sick:

Tintyra cured me; what I saw today repaid me for all my fatigue;

whatever may happen to me as a result of this expedition, I will

applaud myself all my life for having made it through the memories that

this day will leave me eternally."

Footnotes:

1.

[Editor's note:] Abydos had temples and ceremonial complexes

dedicated to the Egyptian god Osiris, and to the pharaohs Seti I

and his son Ramesses II (one of whose many aliases was Ozymandias). For

more information, see Abydos, Parts I and 2, by W.M. Flinders Petrie, 1902-3, Egypt Exploration Fund, Memoirs 21+22; and The Osireion at Abydos, by Margaret A. Murray, 1904, Egyptian Research Account.

2. [Editor's note:] For early excavations at Diospolis Parva, see Diospolis Parva: The Cemeteries of Abadiyah and Hu, by W.M.Flinders Petrie and A.C. Mace, 1901, Egyptian Exploration Fund, London.

3. [Editor's note:] The temple site of Tentyris is now usually called Dendereh or Dendera.

4.

[Editor's note:] The female deity with cow's ears represented at the portal of the temple of

Dendera is now known to be not Isis but Hathor, another major Egyptian diety. For more information, see Dendereh by W.M.Flinders Petrie and D.L. Griffith, 1900, Egypt Exploration Fund, Memoir 17.

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|