| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Voyage in Lower and Upper Egypt, during the Campaigns of General Bonaparte. Vivant Denon | | | | |

|

Chapter 35: Crocodiles. (p.184)

On

the 26th [Jan. 1799], a new nature developed before our eyes: palm

trees, much larger than those we had seen, gigantic tamarisks, villages

half a league long, and yet lands which had been flooded, and who had

remained uneducated. Did the inhabitants only want to cultivate what

would suffice for their food, and thus deprive their tyrants of the

surplus of their work? In the afternoon, chatting with Desaix, he spoke

to me about crocodiles: we were in the part of the Nile where they

inhabit; in front of us were low sandy islands, like those where they

appear; we saw something long and brown through many of the ducks; it

was a crocodile; he was fifteen to eighteen feet tall; (p.185) he was

asleep: a gunshot was fired at him, he gently entered the water, and

came out a few minutes later; a second shot made him go back in, he

came out the same way: I found his belly much bigger than those of

animals of the same species that I had seen stuffed.

Fig.1: Nilotic crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus) drawn

by Redoute and Saint-Hilary, artistic and scientific companions of

Denon in 1798-9. This figure (published in the Natural History

section of Description de l'Egypte,

vol. I, Reptiles, Pl.1, 1809) shows both adult and juvenile

examples of the Nilotic crocodile, the species associated with the god

Sobek. They were frequently mummified and placed in tombs at temples of

Sobek at Tebtunis and other Fayum sites.

We

learned that part of the Mamluks had crossed to the right bank of the

river, and that the other was following the road to Esnê and Syene.

Desaix sent his cavalry out at midnight to try to reach the latter.

On

the 27th, we left at two in the morning; eight of us found a dead

crocodile on the banks of the river: it was still fresh; it was eight

feet long: the upper jaw, the only moving one, fits rather poorly with

the lower one; but his throat makes up for it, it folds like a purse,

and its elasticity acts as a tongue, of which it absolutely lacks: its

nostrils and ears close like the gills of a fish; his eyes, small and

close together, add much to the horror of his physiognomy.

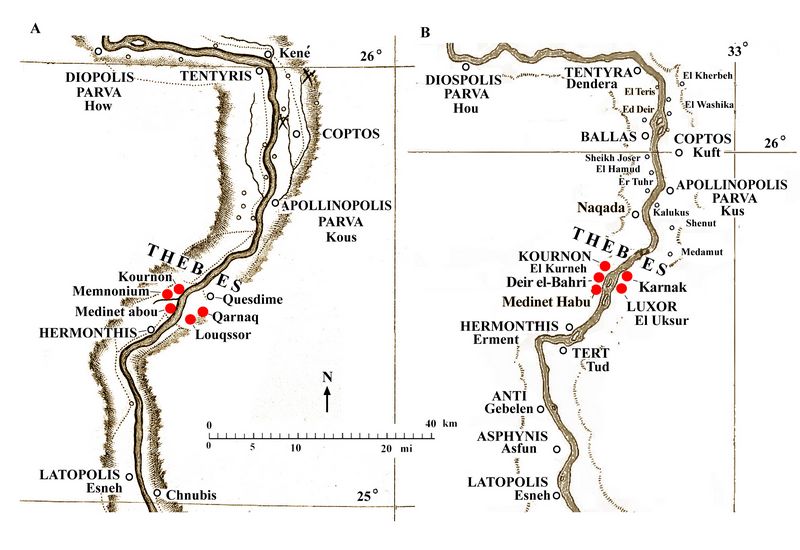

Chapter 36: Thebes. (p.185)

At

nine o'clock, turning around the point of a mountain range which forms

a promontory, we suddenly discovered the location of ancient Thebes in

all its development; this city whose extent is depicted by a single

expression of Homer, this Thebes with a hundred gates; poetic and vain

phrase that has been repeated with confidence for so many centuries.

Described in a few pages dictated to Herodotus [1] by Egyptian priests,

and copied since by all other historians; famous for the number of

kings whom their wisdom placed in the rank of gods, for laws which we

revered without ever knowing them, for sciences entrusted to (p.186)

sumptuous and enigniatic inscriptions, learned and first monuments

arts, respected by time; this abandoned sanctuary, isolated by

barbarism, and returned to the desert from which it had been conquered;

this city finally always enveloped in the veil of mystery by which even

the colossi are enlarged; this relegated city, which the imagination

only glimpses through the darkness of time, was still a ghost so

gigantic for our imagination that the army, at the sight of its

scattered ruins, stopped herself, and, by a spontaneous movement,

clapped her hands, as if the occupation of the remains of this capital

had been the goal of her glorious labors, had completed the conquest of

Egypt.

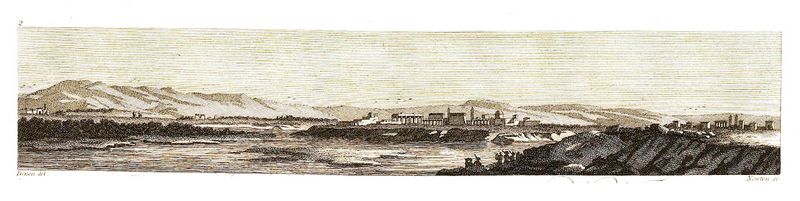

I made a drawing of this first aspect as if I could have

feared that Thebes would escape me (plate 21-2); and I found in the

complacent enthusiasm of the soldiers knees to serve as a table, bodies

to give me shade, the sun illuminating with too ardent rays a scene

that I would like to paint for my readers, to make them share the

feeling that the presence of such large objects made me feel, and the

spectacle of the electric emotion of an army composed of soldiers,

whose delicate susceptibility made me happy to be their companion,

glorious to be French.

Plate 21-2: Panorama of Thebes (Denon, vol. 1, 1802).

"No.

2.—General view of Thebes, taken from the south-east to the north-west,

on the right bank of the river, from where we can see all the monuments

of this city, except that of the village of Damhout; starting on the

right, where we see six birds, the village of Karnak, with its ruins;

in the middle, on a sort of promontory formed by a bend in the river,

that of Luxor; immediately after on the third plane, and on the other

bank of the river, Kournou; following, on the same line, Memnonium, the

two colossal statues, and Medinet-Abou, all crowned by the mountains of

the Libyan chain: the place where we see two birds is that where is the

valley which leads at the tombs of kings; on the left, a cultivated

island, and in the middle, in the foreground, these low islands on

which crocodiles are often seen; this view, which happens to be a kind

of topographical map of four square leagues, in addition to the extreme

interest of its monuments, offers a picturesque aspect by its shapes,

by the movement of the ground, and by the variety of its colors." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

The situation of

this city is as beautiful as one can imagine; the extent of its ruins

does not allow us to doubt that it was as vast as fame has published:

the diameter of Egypt not being large enough to contain it, its

monuments lean on the two ranges which border it, and its tombs occupy

the western valleys well into the desert. I took a view of its

situation from the moment I could distinguish its obelisks and its

famous porticos: I thought that, just as eager as me, my readers would

see with interest the image of such a curious object. 'as far as we can

perceive it, and that in general the first duty of a traveler is to

give an account of all his sensations, without allowing himself to

judge and distort them. This is why (p.187) I made it a law to engrave

my drawings as I made them from nature: and I tried to preserve in my

journal the same naivety that I put in my drawings. Four villages

compete for the remains of the ancient monuments of Thebes; and the

river, by the sinuosity of its course, still seems proud to cross its

ruins.

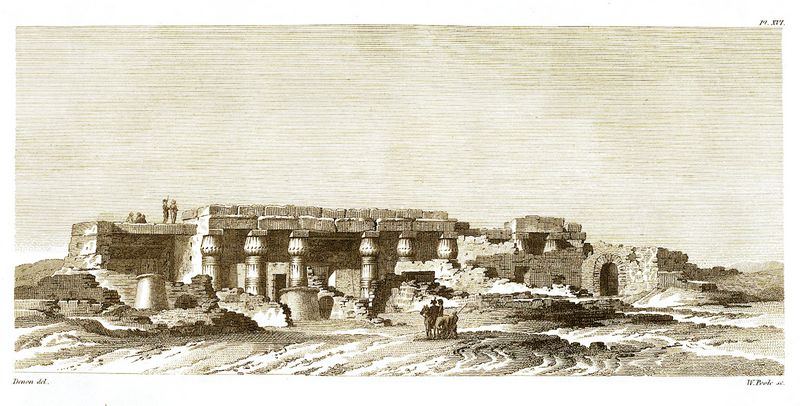

Plate 16:

"View of a temple of Thebes at Kournou; it is cluttered with bad modern

structures, which are very picturesquely composed with the severity of

the ancient style of the monument and its state of dilapidation; its

shape, different from the other temples, would have made the plan

interesting; but, apart from the difficulty presented by the ruin of

the building, circumstances never allowed me to undertake it; its

burial and the heaviness of its dimensions further add to the colossal

aspect of its effective size." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Between noon and one o'clock, we arrived at a

desert which was the field of the dead: the rock, cut into its inclined

plane, presents regular openings in the three faces of a square, behind

which double and triple galleries and chambers served as burials. I

entered there on horseback with Desaix, believing that these dark

retreats could only be the asylum of peace and silence; but we had

barely entered the darkness of these galleries when we were assailed

with javelins and stones by enemies whom we could not distinguish;

which put an end to our observations. We have since learned that a

considerable population inhabited these obscure retreats; that

apparently contracting fierce habits, she was almost always in

rebellion with authority, and became the terror of her neighbors: too

eager to make better acquaintance with the inhabitants, we retrograded

with precipitation; and this time we only saw Thebes at a gallop.

Plate 17-1: View of necropolis.

"No.

1.— Necropolis of Thebes, located northwest of this city, on a plateau

in the lower part of the Libyan chain: this deserted and arid part was

by its nature devoted to the silence of death. By cutting the rock on

an inclined plane, three sides quite naturally offered escarpments, in

which double galleries were dug, and behind them, sepulchral chambers;

these excavations are innumerable, and occupy a space of more than half

a square league; They now serve as housing for the inhabitants of the

village of Kournou, and their numerous herds. It would be very

interesting to observe the details of these tombs: but the first time I

saw them, I entered there with Dcsaix, and we thought we would be

killed with pikes by the inhabitants who had hidden there; the second

time they fired guns at us there; the last time we went there to make

war on the inhabitants, and, once peace was made, we did not want to

torment them with a home visit." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

My fate was to stay for months at Zaoïé, at

Bénisouef, at Girgé, and to pass without stopping over the large

objects that I had come to look for. We arrived a moment later at a

temple, which I had to judge to be the oldest by its dilapidation, its

more pronounced color of dilapidation, its less perfected construction,

the excessive simplicity of its ornaments, the irregularity of its

lines. , its dimensions, and above all the crudeness of its sculpture.

I quickly began to make a drawing of it, then, galloping after the

troops who were still marching, I arrived at a second building, much

larger and much better preserved (pl;ate 17-2). I found on the way (p.188) what is

this material that has long been called basalt, and of which the

magnificent Egyptian lions which are at the bottom of the ramp of the

Capitol are made.

At its entrance two square piers flank an immense door:

against the interior wall are sculpted in two bas-reliefs the

victorious battles of a hero; this sculpture is of the most baroque

composition, without perspective, without plan, without distribution,

and like the first conceptions of the human mind which always has the

same march. At Pompeia I saw drawings made by Roman soldiers on the

stucco of the walls; they entirely resembled our drawings, those of any

child who wants to convey his first ideas, when he has not yet seen,

compared, or reflected. Here the hero is gigantic, and the enemies he

fights are twenty-five times smaller: if this was already a flattery of

the arts, it was undoubtedly misunderstood, since it must have been

shameful for this hero not to having to fight only pygmies.

A

few steps from this door are the remains of an enormous colossus; it

was badly broken, because the spare parts have so preserved their

polish, and the fractures their edges, that it is obvious that if the

devastating spirit of men had allowed them to entrust time alone with

the task of ruining this monument, we would still enjoy it in its

entirety; it suffices to say, to give an idea of its size, that the

width of the shoulders is twenty-five feet, which would make the whole

figure approximately seventy-five feet; exact in its proportions, the

style is mediocre, but the execution perfect; in his fall he fell on

his face, which prevents us from seeing this interesting part; the

hairstyle being broken, we are no longer in the position of judging by

its attributes whether it was the figure of a king or a divinity: was

it the statue of Memnon or that of Ossimandue? ....The descriptions

made so far, compared on (p.189) places to monuments, rather confuse

ideas than clarify them.

Plate 17, No. 2: The Memnonium.

"View

of what is commonly called Memnonium [1] on the left bank of the Nile. (See

the plan, Plate XXVII.) To the left of the view is the ruin of a large

gate, covered with barbarously composed bas-reliefs, representing a

battle; between this large door and another is an overturned colossus,

whose ruined fragments resemble the site of a quarry; the entire

monument runs from east to west, and reaches almost to the base of the

Libyan chain: the trees that we see are doum palms; and below the trees

is the ruined one, the only column which remains in the base of the

statue, which could have been brought to my courtyard, and the

beginning of the avenue in Europe, and which could have given an idea

colossal columns; to the right of the door of the colossal proportion

of these species of the south is a cistern; on the foreground with

Egyptian monuments. left part of the village of Karnak." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

If it were that of Memnon, which is

most probable, all travelers for two thousand years would have been

mistaken in the object of their curiosity, as we see by the inscription

of their name on another colossus, of which I will have to speak later.

There remains a foot of this first statue, which is detached and well

preserved, very likely to be transported, which could give in Europe a

scale of comparison of monuments of this type, and make a counterpart

to the colossal feet which are in the courtyard of the Capitol in Rome.

The enclosure in which this figure is located was either a temple, or a

palace, or perhaps both at the same time; for if the bas-relief was

suitable for a sovereign's palace, eight figures of priests in front of

two interior porticos were also suitable for a temple, unless they were

there to remind the sovereign that, in accordance with the laws,

priests must always serve and assist His Majesty. Moreover, this ruin,

located on the slope of the mountain, and having never been inhabited

in later times, is so well preserved in its still standing parts that

it has less the appearance of a ruin than of a building that is being

built, and whose work is suspended: we see a number of columns right

down to their bases; the proportions are large, but the style, although

purer than that of the first temple, is nevertheless not comparable to

that of Tintyra, neither for the majesty of the whole, nor for the

delicacy of the execution of the details. It would have taken time for

reflection to come up with the plan; but we had taken the galloping

movement, and we had to follow closely so as not to be stopped forever

in our observations.

We were attracted into the plain by two

large seated figures (plate 19), between which, according to the descriptions of

Herodotus, Strabo, and those who copied these writers, was the famous

statue of Ossimandue, the greatest (p.190) of all the colossi:

Ossimandue himself had been so glorious of the execution of an

enterprise so daring, that he had an inscription scratched on the

pedestal of this statue, in which he defied the power of men to attack

this monument as well as that of his tomb, whose sumptuous description

seems only a fantastic dream. The two statues still standing are

undoubtedly those of the mother and son of this prince, of whom

Herodotus mentions; that of the king has disappeared; time and jealousy

having fought over its destruction, all that remains is a shapeless

granite rock; it takes the stubborn gaze of the observer accustomed to

seeing to distinguish some parts of these figures which have escaped

destruction, and even then they are so insignificant that they can give

no idea of its dimension: the two which are still existing have fifty

to fifty-five feet in proportion; they are seated, both hands on their

knees: what remains of them shows that the style was as severe as the

pose was straight.

Plate 19: Colossal statues,

"No.

1.—The two statues which we agree to call the statues of Memnon, on one

of which are inscribed the names of the learned and illustrious Greek

and Latin personages who came to hear the sounds she made, they say,

when she was struck by the first rays of dawn; among these names we

find that of the Empress Sabine, wife of Adrian."

"I chose

the moment of sunrise, the moment when travelers arrive to hear; .and

which at the same time presents these monuments in a historical manner,

orients them, and shows the effect of the trail of shadow projecting to

the base of the Libj'-que range, covered with tombs. The ruin that we

see beyond the statues is that of Memnonium."

"No. 2 and 3.—The

state of destruction of the above figures. I made a faithful portrait

of the breaks, and put the living figures in exact proportion. No. 2 is

the one that is forward in view; it is drawn at its northern part; that

No. 3 is the other statue taken, from its southern part, and which we

have agreed, I do not know by what preference, to call the statue of

Memnon; at least it is on its legs that the names of those who came to

hear it are inscribed in Greek and Latin. It should be noted that Nos.

2 and 3 are two drawings made separately, that the direction of these

two figures is the same, and that if the latter seem to turn their

backs on each other, it is because the sun was so hot when I made the

drawings, that it could only be in the shadow of one that I was able to

draw the other. They are 55 feet high; they are in one piece; placed on

high ground, and are visible from five leagues." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

The

bas-reliefs and small figures which make up the armchair of the one

further south, however, lack neither charm nor delicacy in execution;

It is against the leg of the northern one that the names of the

illustrious and ancient travelers who came to hear the sounds of the

statue of Meranon are written in Greek. It is here that we can be

convinced of the empire of fame over the minds of men, since, in times

when the ancient Egyptian government and the jealousy of the priests no

longer allowed foreigners to approach these monuments, the love of the

marvelous still acted on those who came to visit them; that in the

century of Adrian, enlightened by the lights of philosophy, Sabine, the

wife of this emperor, who herself was literate, wanted, as did the

scientists who accompanied her, to have heard sounds, which no physical

reason nor politics could no longer produce: but the pride of

memorializing his name by inscribing it (p.191) before such antiquities

could very well have caused the first names to be written, and the very

natural desire to associate his own with this kind of glory will have

added others to it; this is undoubtedly the cause of these innumerable

inscriptions of names from all dates and in all languages.

I had

barely begun to draw these colossi when I realized that I had been left

alone with my sumptuous originals, and the thoughts that their

destitution inspired in me; frightened of where I found myself, I

galloped again to catch up with my curious companions, who had already

arrived at a large temple, near the village of Medinet-Abou. I observed

while running that the site of the tomb of Ossimandue was cultivated,

that consequently the flood reached there; which proved either that the

bed of the Nile was raised, or that formerly there had been some quay

or dike to prevent the waters from flooding this part of the city,

which, at the time when we crossed it, was a vast field of very green

corn, which promised an abundant harvest.

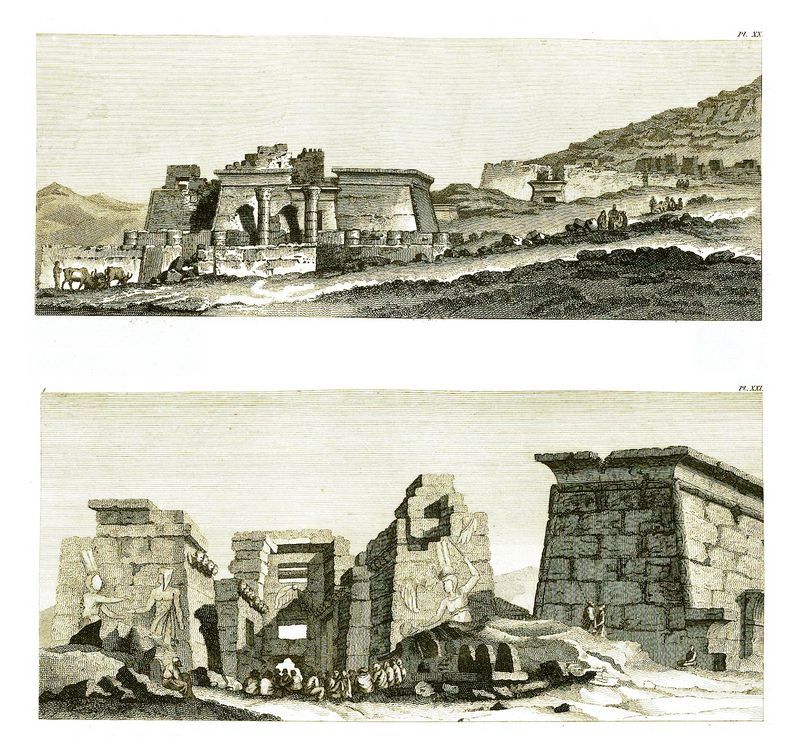

Plate 20-1 (top): Medinet-Abou temples.

"No.

1.—General view of the temples and palaces located near the village of

Medinet-Abou in Thebes. The plan, Plate XXVIII, can provide insight.

The part in front is that marked figure first; it was never finished,

and we can still see in bossage what was intended to be sculpted in

bas-relief; behind, to the left, marked in the plan fig. 3, is the ruin

of the small palace, the view of which is made apart." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Plate 21-1 (bottom): The

small palace which is near the great temple of Medinet-Abou (shown at

right) is the only monument which is obviously not a temple, and yet it

was still adjoining it; it has a floor, windows, small doors, a

staircase, balconies as solidly constructed as sacred buildings; it is

also covered with bas-reliefs: circumstances have never given me the

freedom to draw them; the bases to support the balconies are very

extraordinary, and the only ones I have seen of this kind; it is the

same thought as that of the caryatids: another singularity is the

crenellated facings, which we see in the middle of the print, which I

have not found anywhere else, and of which I have not been able to on

the places imagine the use. I have since been told that among the

bas-reliefs there are some which represent licentious scenes; they

escaped me: when we approach monuments of such extraordinary antiquity

and of such a particular form, we experience such preoccupation, such

agitated curiosity, that we look without seeing, and that for the most

part we leave them with as much worry and regret as enthusiasm." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

To the right and adjoining the village of

Medinet-Abou, at the bottom of the mountain, is a vast palace built and

enlarged at various times. What I was able to observe positively in the

speed of this first examination, which we carried out on horseback, was

that the back of this palace, which leans against the mountain, and

which seemed to me to be the oldest part built , was covered with

hieroglyphics, very deeply dug, and without any relief; that

Catholicity, in the fourth century, took possession of this temple, and

made it a church, adding two rows of columns in the style of the time,

to be able to support a roof. To the south of this monument, there are

Egyptian apartments with square windows and stairs; it was the only

building I had yet seen that was not a temple; next to it, factories

rebuilt with older materials in front of which are a facade and a

courtyard which were never completed. It was (p.192) It was rather a

glance, a recognition made at haste than a real exam. The first thirst

of curiosity satisfied, Desaix galloped again as if he had seen the

Mamluks on the plain; he took us two more leagues from there to sleep

at Hermontis, where for my part I was lodged in a temple.

Footnotes:

1.

[Editor's note:] The site named Memnonium by Denon corresponds to part

of the site of Deir el-Bahri, which contains large temples and tombs

from the 11th and 12th dynasties, and in the New Kingdom, a major

temple complex for Queen Hatshepsut of the 18th dynasty (reigned

1474-1458 BC). Early excavations were undertaken for the Egyptian

Antiquities Dept. by Maspero and Brugsch in the 1870s, by Naville for

the Egyptian Exporation Fund in the 1890s - 1913 (Naville, Édouard, The

Temple of Deir el Bahari, EEF, vols 12-14, 16, 19, 27, 29, London, 1894-1898; and The XIth Dynasty Temple at Deir el-Bahari, EEF, vols. 28, 30, 32, London, 1907-1913); and

by Winlock for the Metropolitan Museum (Winlock, Herbert E.,

Excavations at Deir el-Bahri, 1911-1931, New York: Macmillan, 1942.)

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|