| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Voyage in Lower and Upper Egypt, during the Campaigns of General Bonaparte. Vivant Denon | | | | |

|

Chapter 31: The White Convent.—Ptolemeis. (p.157)

On

the 28th, we crossed a desert, and came to a Coptic convent, which the

Mamluks had set fire to the day before, and which was still burning;

which prevented me from entering: but we will know the details from

those which I am going to give of the White convent, which resembles

it, and which is only twenty minutes' walk from the other, situated in

the same way. under the mountain, and likewise on the edge of the

desert; the first is called the Red Convent, because it is built of

bricks; the other the White Convent, because it is made of cut stones

of this color: the latter had also been burned the day before; (p.158)

but the monks, while fleeing, had left the door open, and a few

servants to save the debris.

Plate 10-1:

The White Convent.

"No. 1.—Deir Beyadh or the White Convent, the view of which is taken from north to south over the Abou-Assan canal."

"In

the plan and interior decoration we easily recognize the taste of

architecture of the fourth century, in which Catholicity began to build

for its worship: with quite beautiful plans, poor details, and the use

of antique materials poorly matched, the exterior of poorly matched

antique materials, the exterior is more of the Egyptian style than any

other, the main lines and the general embankment of the whole building

are still imitations of it; it is a square 250 by 125 feet long,

pierced with three doors, and two rows of twenty-six crosses, for each

row on the long sides, and nine on the other side. See the plan, No. 2.

The mountain against which this convent is leaning is part of the

Libyan chain." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

The erection of this

building is attributed to St. Helena [1]; which is likely judging by

the plan. There was undoubtedly a convent near this temple; some wall

tears and granite blocks attest to its former existence. Looking at

these monuments, we must think that if it was St. Helena who had them

built, the Emperor Constantine supported her zeal and placed large sums

at her disposal; the convent not being, like the church, built in such

a way as to be able to enclose and defend itself, will undoubtedly have

been burned or destroyed in circumstances similar to that of which we

had just witnessed: the construction of this church is also such that

with a machicouli on the doors and a few pieces of cannon on the walls

we can defend ourselves very well against the Arabs, and even against

the Mamluks; but, without weapons, these poor monks could only oppose

patience, resignation, their holiness, and above all their misery which

in any other occasion would have saved them; in this one, the Mamluks

took revenge on Catholics for the evils they experienced against

Catholics: as if they could repair by such an unjust means the

misfortunes of which we were the cause. We saw in the ruins produced by

this catastrophe the coal which resulted from the fire of the choir

woodwork; and the insatiable needs of the insatiable war made us once

again remove these debris of misery, and these remains of the

devastation of which we were the cause.

(p.159) The

fathers had fled; we only found the brothers, covered in rags, and

barely recovered from the agony they had experienced the day before. To

get an idea of the life, character, and means of subsistence of these

monks, one must read what General Andréossi wrote about them in the

excellent memoir he gave on the lakes of Natron, and the convents of EI

- Baramous, Saint - Ephrem, and Saint - Macaire; this exact and

judicious observer described the needs of these monks, their state of

continual war with the Arabs, the misfortunes of their existence, the

moral causes which make them endure them and perpetuate these

establishments.

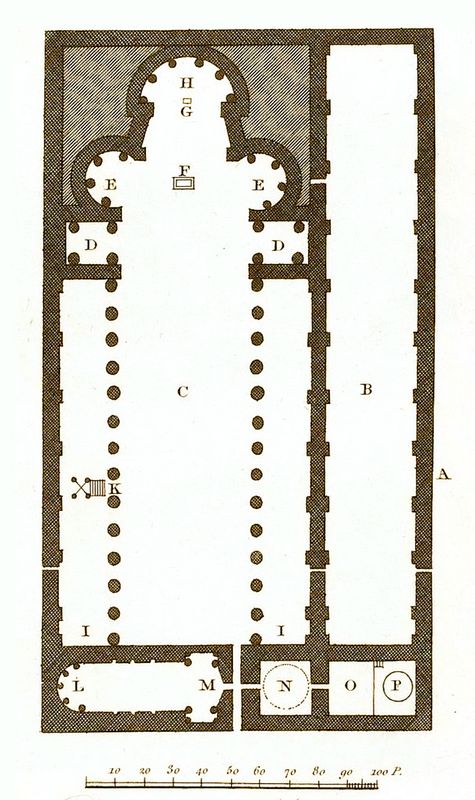

Plate 10-2: Plan of the White Convent.

"No.

2. The interior consists of a large side gallery B, through which one

enters, and which could have been the place where the proselytes who

had not been baptized were held; this room is decorated with porticos

topped with a cornice; parallel porticos topped with a cornice;

parallel to this gallery was nave C, decorated with sixteen arches and

pilasters, and two rows of sixteen columns each; the choir, composed of

a cu-de-four II, and four chapels EE and DD, decorated with two orders

of columns: in the cu-de-four and the two neighboring chapels, the two

orders are surmounted by a shell which serves as their crowning glory.

All these columns ARE so many ancient fragments adjusted in bad taste;

the pulpit for the epistle, K, and the staircase which goes up to it,

are made of two enormous pieces of granite: what remains of the paving

stone in the choir is in beautiful breccia marble, but absolutely

degraded; the nave is paved with large pieces of granite - where we can

still see hieroglyphics. At the end of the nave, across the width of

the temple, is a chapel, decorated in very good taste, in a single

order: behind the altar, L, five columns supporting an entablature

crowned with a shell: the lateral parts are decorated with three

niches; the whole finished by a square portico, M, supported by four

columns; it was perhaps the place where Christians made their act of

faith: next to it, N, were the baptistery, and a superb cistern, P." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

While we were stopping, I took two views of it

as quickly as I could. One (plate 10-1) is drawn from the Red convent to the White

convent, which indicates the space between them, and the situation of

these two monasteries leaning against the desert, and having the view

of a rich countryside watered by the canal of Abou-Assis: the other

(plate 10-2) gives the idea of the architecture of these buildings of the fourth

century, consequently twenty centuries later than the great Egyptian

monuments, and whose gravity of style, the cornice and the doors

absolutely recall the genre of this first architecture; the plan shows

beautiful lines, except in the part of the choir, where we recognize

the decadence of good taste. We went to bivouac at Bonasse-Boura.

On

the 29th, we returned to the Nile, and we crossed the battlefield

where, in the last war of the Turks with the Mamluks, Assan pasha was

defeated by Mourat-bey, and where the latter, with five thousand

Mamluks, overthrew and put eighteen thousand Turks and three thousand

Marmelouks fled. Malem-Jacob, the Cophte, who accompanied us as steward

of the finances, spectator and actor in this battle, explained the

details to us: he demonstrated to us with what superiority of talent

Mourat had (p.160) taken his advantages and had profited; this same

Mourat-bey must have roared with anger at being forced to return to the

same ground fleeing in front of fifteen hundred infantry men. As we

reasoned about the vicissitudes of fortune, carried away by the

interest of conversation, we very imprudently, as happened to us every

day, got ahead of the army by half a league.

I

said jokingly to Desaix that it would be very ridiculous to find in

history that his neck had been cut in a meeting of five or six Mamluks,

and that for my part I would be sorry to leave my head behind some

bushes, where she would be forgotten: at this moment we were passing

Minchie; Adjutant Clément came to tell the general that there were

Mamluks in the village: in fact two appeared, then six, then ten, then

four others, then two others, then crews; they went to stand within

rifle range, and observed us: to backslide would have been to be

kidnapped; the country was covered: Desaix decided to put on a good

face, to appear to be making arrangements; he had four riflemen, whom

he placed alternately on all points, in order to multiply them by their

movements: we put some ditches between the Mamluks and us; we gained

time; our vanguard finally appeared, and they withdrew.

Fig.1: (left:) Detail of map of upper Egypt, with locations of sites named in the text,

(Denon

1802 vol.3, plate 1); (right:)

Archaeological site map of the early 20th century, including

sites named by Denon but not shown on the 1802 map (red dots),

(Atlas of the Egyptian

Exploration Fund, ca. 1910).

They

came to tell us that Mourat was waiting for us in front of Girgé; we

heard loud cries, we saw clouds of dust rising; Desaix believed he had

won the battle after which we had been chasing for fourteen days: I was

sent to advance the infantry column; I noticed, as I galloped past, an

ancient covering on the edge of the Nile, and stepped ramps descending

into two basins: were these the ruins of Ptolemais? . . . . A cannon

was fired to bring back the cavalry which had lain a league from us;

after half an hour, we found ourselves in a state of defense or attack:

we marched in battle on the gathering, which dissipated; the (p.161)

amelouks themselves disappeared, and we arrived at Girgé without having

joined the enemies.

Sitting near his desk,

the map in front of him, the pitiless reader said to the poor traveler,

harassed, pursued, hungry, exposed to all the miseries of war, I need

here Aphroditopolis, Crocodilopolis, Ptolemais; what have you done with

these cities? What did you go there to do if you can't tell me? have

you not a horse to carry you, an army to protect you, an interpreter to

question you? Did you not think that I would honor you with my

confidence?—At the right time; but please, reader, remember that we are

surrounded by Arabs, Mamluks, and that very probably they would have

kidnapped, pillaged, killed me, if I had decided to go a hundred paces

from the column to fetch you some bricks of Aphroditopolis.

This paved quay, which I saw while galloping past Minchie, was Ptolemais; nothing else remains.

A

little more patience, and we will go together to tread brand new ground

for research, to see what Herodotus himself only described using false

accounts, what modern travelers have only been able to draw and measure

with all kinds of anxiety, without daring to lose sight of the Nile and

their boat: in fact these unfortunate travelers, ransomed in turn and

under all kinds of pretexts by the reis, by their interpreter, by all

the sheikhs, kiachefs and pashas, abandoned by their own, stolen from

others, suspected as sorcerers, tormented for the treasures they were

supposed to have found or for those they were going to look for,

obliged while drawing to keep an eye on all those around them, and who

were always ready to rise up and attack the work, if they did not go so

far as to attack the person; these travelers, I say, are not so guilty

of not transmitting (p.162) all the details that one could desire about

this country so curious, but so dangerous to observe.

Thanks to

the courageous obstinacy of the brave Mourat-bey who will try the fate

of war, we will continue to pursue him, and we will finally enter the

promised land.

Chapter 32: Girgé.—News of Darfur, and Tombout (p.162).

Girgé,

where we arrived at two o'clock in the afternoon, is the capital of

Upper Egypt: it is a modern city which has nothing remarkable; she is

as big as Mynyeh and Melaui; less large than Siouth; and less pretty

than all three: the name of Girgé or Dgirdgd comes from a large

monastery, built older than the city, dedicated to St. George, which is

pronounced Qerg-e in the language of the country;, the convent still

exists, and we found European monks there. The Nile comes crashing

against the constructions of Girgé, and daily demolishes part of them;

we would only make it a bad port for boats at great expense: this city

is therefore only interesting because of its position at an equal

distance from Cairo and Syene, and by that. wealth of its territory, We

found all the edibles there at a very low price; penny bread the pound;

twelve eggs for two sous, two pigeons for three sous, a goose weighing

fifteen pounds for twelve sous. Was it poverty? no, it was abundance;

because, after a stay of three weeks, where more than five thousand

people had increased consumption and spent money, everything was still

at the same price.

The boats (p.163) did not join us; we lacked

shoes and biscuits: we settled down, had ovens built, barracks prepared

to station five hundred men: the troop rested; and I personally found

the advantage of refreshing my eyes, which were threatening to cease

service altogether. I had no help from any remedy; but a pot of honey

that I found in the house of a sheikh where I was staying, and a jar of

vinegar, took my place: I ate of the first until indigestion, and

calmed the heat of my blood by drinking the other with water and sugar.

On

December 30, we learned that peasants, seduced by the Mamluks, were

gathering behind us to attack us from behind, while they were promised

to attack us in front. It was only a month since they had robbed a

caravan of two hundred merchants who were coming from India by the Red

Sea, Cosseïr, and Quss; they believed themselves to be brave: forty

insurgent villages had gathered six to seven thousand men; a charge of

our cavalry which slaughtered a thousand to twelve hundred taught them

that their project was worthless.

We found a Nubian prince in

Girgé: he was brother of the sovereign of Darfur [2]; he was returning

from India, and was going to join another of his brothers who

accompanied a caravan of eight hundred Nubians from Sennar with as many

women: elephant teeth and gold powder were the goods he carried to the

Cairo, to exchange them for coffee, sugar, schals and sheets, lead,

iron, senna, and tamarind. We talked a lot with this young prince, who

was lively, cheerful, ardent and witty; his physiognomy depicted all

this: he was more than tanned; very beautiful and well-set eyes; the

nose slightly raised, but small; the mouth is very flat, but not flat;

legs like all Africans, slender and arched: he told us that his brother

was allied with the king of Bournou, that he (p.164) traded with him,

and that he waged perpetual war with those of Sennar; he told us that

from Darfur to Siouth there were forty days of crossing, during which

they only found water every eight days, either in cisterns or as they

passed through the Oases. The profits from these caravans must be

incalculable to compensate those who bring them together for the

expenses they have to incur, and pay them for the excess of their

fatigue.

When their female slaves are not captives, and they buy

them, they cost them a bad gun; and the men, two. He told us that it

was very cold at his place during one time of the year; having no words

to describe ice cream, he told us that we ate a lot of something which

was hard when held in the hand, and which slipped out of the fingers

when held for a while.

We spoke to him about Tombout, this

famous city whose existence is still a problem in Europe. Our questions

did not surprise him: according to him, Tombout was in the southwest of

his country; its inhabitants came to trade with them; it took them six

months to arrive; They sold them all the objects they came to collect

in Cairo, and were paid for them with gold powder: this country was

called Paradise in their language; finally the town of Tombout was on

the edge of a river which flowed to the West; the inhabitants were very

small and gentle. We greatly regretted having had this interesting

traveler for such a short time, whom we could not, however, question to

the point of indiscretion, but who would have asked nothing better than

to tell us many things, having none of the Muslim seriousness, and expressing himself with energy and ease.

He

also tells us that in the royal family the succession was elective,

that it was the military and civil leaders who chose from among the

sons of the dead king the one they judged most worthy to succeed him to

the throne, and that he There was as yet no example of this having

produced (p.165) civil war. Everything we have just read is word for

word the report of the interrogation that we subjected to this strange

prince: he added that we had infinitely many things to provide to

Africa; that we would very voluntarily make it our tributary, without

harming the trade that they themselves had to carry on, and that we

would attach them to our interests by all their needs, and by the

export of all the surplus of our productions; that the trade of India

would be carried out in the same way through Mecca, taking this city or

that of Cosseïr as a common warehouse, as Aleppo was for that of the

Muslim states, despite the length of the marches which had to be made

from each side to arrive at this point of contact.

Footnote:

1.

[Editor's note:]

St. Helena (Flavia Julia Helena, AD 248-330) was the mother of the

emperor Constantine I (the Great), who in AD 313 established

Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire.

She founded a number of early Christian monasteries and basilica,

including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

2.

[Editor's note:] Darfur, a region in southwestern Sudan, was founded by

emigrants from Meroe in ca. AD 350, and remained an independent

sultanate until conquered by the Sudanese in 1874.

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|