| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Voyage in Lower and Upper Egypt, during the Campaigns of General Bonaparte. Vivant Denon | | | | |

|

Chapter

27: Benesech, the ancient Oxyrhynchus. - Desert Picture. - Pillage of Elsack. (p.143)

Benesech

was built on the ruins of ancient Oxyrhynchus, capital of the

thirty-third nome or province of Egypt; all that remains of its ancient

existence are a few sections of stone columns, marble columns in the

mosques, and finally a standing column, with its capital and part of

its entablature, which announce that this fragment made the angle of a

composite gantry. The desire to draw, especially since I rarely found

the opportunity, had made me take the lead: it was not without some

danger that I had arrived alone half an hour before the division; but

to stay afterwards would have been even more perilous: I therefore only

had time to ride on horseback and take a view of this sad country, and

to draw the only standing column which remained of its former splendor:

from this point we sees a monument emerging from the hands of nature

and time, which, instead of exciting admiration and recognition,

carries in the soul a melancholy feeling; Oxyrynchus, formerly the

capital, surrounded by a fertile plain, two leagues from the Libyan

chain, has disappeared under the sand; the ancient Benesech, beyond

Oxyrynchus, has also disappeared under the sand; the new city is forced

to flee this scourge by abandoning a few homes to it every day, and

will end up entrenching itself beyond the Jusep canal, on the edge of

which it still threatens it.

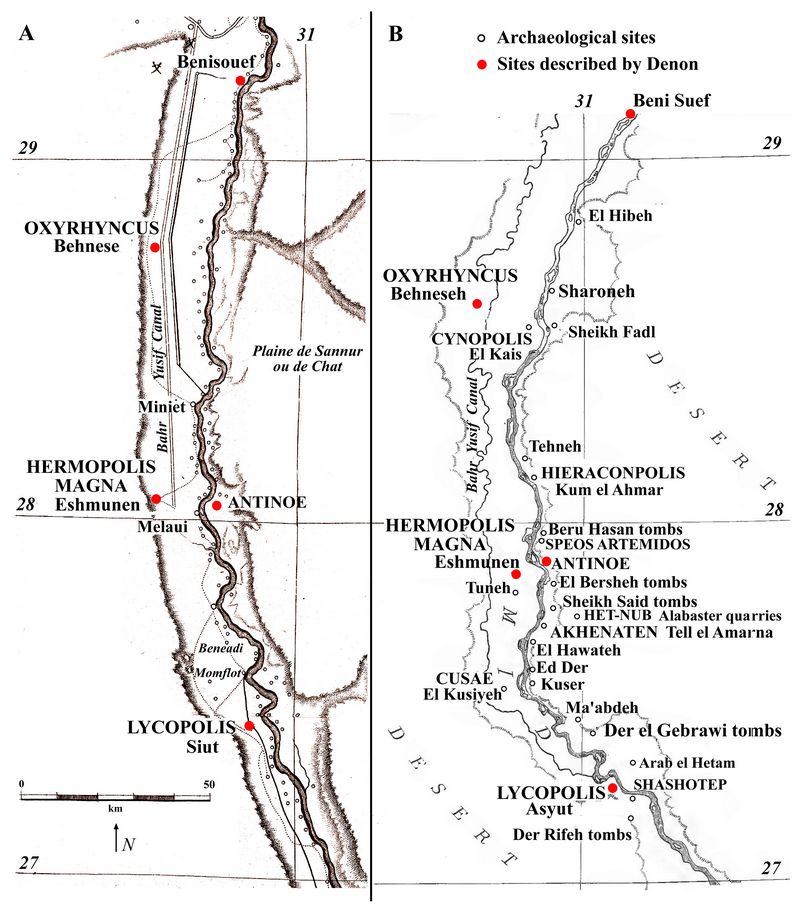

B)

Archaeological site map of the early 20th century, including the sites

described by Denon (red dots), based on Atlas of the Egyptian

Exploration Fund (ca. 1910). [Note the many sites later known on the

east bank of the Nile, including Tell-el-Amarna. Ptolemaic or

Graeco-Roman site names are in capital letters.]

This

beautiful canal seems to offer you its flowery banks to console your

eyes from the horrors of the desert; of the desert! terrible name to

those who have seen it once, boundless horizon, whose space oppresses

you, whose surface presents to you if it (p.144) it is united only a

painful task to traverse, where the hill does not hides or reveals to

you only decrepitude and decomposition, where the silence of

non-existence reigns alone over the immensity. This is undoubtedly why

the Turks will place their tombs there: tombs in the desert mean death

and nothingness.

Tired

of drawing, I indulged myself, believing myself alone, in all the

melancholy that this painting inspired in me, when I saw Desaix in the

same attitude as me, penetrated by the same sensations: My friend, he

said to me, this Is it not an error of nature? nothing receives life

there; everything seems to be there to sadden or terrify; it seems that

Providence, after having abundantly provided the three parts of the

world, suddenly lacked an element when it wanted to make this one, and

that, no longer knowing how to do it, it abandoned it without finish

it.—Isn't it rather, I said to him, the decrepitude of the most

anciently inhabited part of the world? Would it not be the abuse that

men would have made of it which reduced it to this state? In this

desert there are valleys, petrified woods.; there were therefore

rivers, forests; the latter will have been destroyed; from then on no

more dew, no more fog, no more rain, no more river, no more life, no

more nothing. We found in the mosques of Benesech a quantity of columns

of different marbles, which are undoubtedly the remains of the ancient

Oxyrynchus, but which did not belong to the time of the Egyptians.

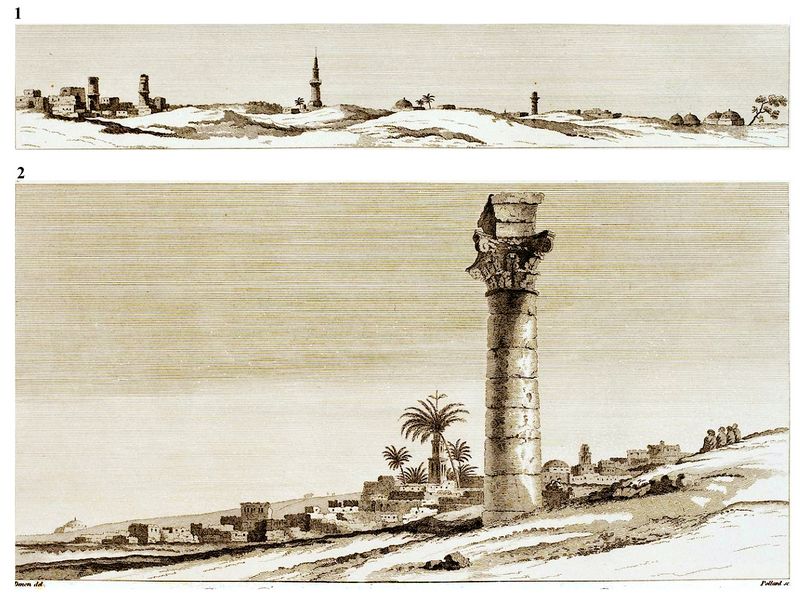

"No.

1. (top)- View of Bénécé or Béneséh, on the canal called Bar-Jusef, the

ancient Oxyrhynchus, capital of the thirty-third nome, cited by the

first Catholics as a considerable city .... This sad view of

Bénécé is particular in that it offers the appearance of the sands

marching over the towns and villages: the right part of the print was

inhabited, and has disappeared; the one where the column is is almost

buried; the one where the minaret is is already abandoned; the one on

the left where there are two towers, is the modern village which seems

to withdraw and flee before the desert which marches on it."

"No.

2 (below) is the view of a ruin, which appears to be that of the corner

of a large, Composite portico, of which only a column and part of the

architrave remain: I do not I had no means of measuring the height of

the column, but its diameter at the quarter of the shaft, where it

leaves the sands which bury it, is four and a half feet; there remain

seven visible courses, forty inches each. This stone building was of

mediocre workmanship; the capital is heavy, although deprived of its

leaves and its volutes, which must make it judge Roman, and later than

Diocletian, that is to say from the time of the decadence of

architecture." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

We

set off again following the canal, which in this part resembles the

Marne: after a league, we saw a considerable explosion, the sound of

which we did not hear; we thought it was a signal; it was only two days

later that we learned that it was part of the Mamluk gunpowder that had

caught fire: a quarter (p.144) quarter of an hour later, we seized a

convoy of eight hundred sheep, which I believe we pretended to believe

belonged to them; finally he consoled our troop for the fatigue of this

great day. We arrived at Elsack too late to be able to save this

village from pillage; in a quarter of an hour nothing remained in the

houses, nothing in the accuracy of the word; the Arab inhabitants had

fled into the fields: they were told to return; they replied coldly:

What would we seek at home; Are these deserted fields not like our

homes to us? We had nothing to respond to this laconic sentence.

Chapter

28: Continuation of the Journey into Upper Egypt. - Mynyeh (p.145).

The

next day, the 20th [Dec. 1798], did not offer anything very

interesting. We found Lake Bathen tortuous like Lake Jusep: the

leveling of the soil of Egypt will one day give us the cut, and will

clarify for us the dark history of its irrigations, both ancient and

modern; before this operation, all reasoning would be reckless, and

assertions illusory. We came to sleep in Tata, a large village,

inhabited by the Cophts, and an Arab chief, who had joined Mourat-bey,

leaving at our disposal a beautiful house, and mattresses on which we

spent a delicious night: we could so rarely sleep with such convenience!

The next day, December 21, we crossed fields of peas and beans already in grain, and barley in flower. (p.146)

At

noon we arrived at Mynyeh, a large and pretty town, where there was

once a temple to Anubis. I found no ruins there, but beautiful granite

columns in the great mosque, well tapered columns, with a very fine

astragalus: were they part of the temple of Anubis? I do not know ; but

they were surely from a later time than those of the temples of ancient

Egyptian antiquity which I saw during the rest of my journey.

The

Mamluks had left the town of Mynyeh, and had almost been surprised by

our cavalry which arrived there a few hours later; they had been

obliged to abandon five buildings armed with ten pieces of cannon and a

bomb mortar; they had buried two others: several Greek deserters who

were riding them came to join us. Mynyeh was the prettiest little town

we had yet seen; quite beautiful streets, good houses, very well

located, and the Nile flowing in a large and flowing basin. I made a

drawing of it.

From Mynyeh to Come-êl-Caser, where we slept, the

countryside is more abundant and richer than all those we had traveled,

and the villages so numerous and so close together, that in the middle

of the plain I counted twenty-four of them around me; they were not

saddened by mounds of rubble, but so planted with dense trees that we

thought we were seeing the pictures that travelers have transmitted to

us of the habitations of the islands of the Pacific Ocean.

Chapter 29: Achmounin. - Antinoe [1]. - Portico of Hermopolis (p.146).

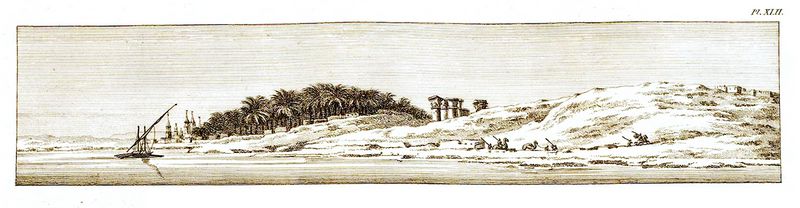

"No.

2.—Antinoë seen from the Nile: we can read in the Journal, page 344,

why I did not give other details on what remains of this city; what we

can see is a gate or a triumphal arch which is at its southern end;

what we see on the right are some Arab dwellings on the site of ancient

Besa, the ruins of which seemed to me to extend from there to the

south-east: the palm forest is planted between the ruins of Antinoe and

the Nile; beyond the village and sanctuary of Schek-Abade, whose

inhabitants have constantly been very unhospitable." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Fig.2: View of the Theater Portico in Antinoe. (From Description de l'Egypte vol.4, 1817, plate 55; drawn by Cecile.)

"This

view is taken from the north side.... It shows the current

state of the facade of the portico and the debris of columns and

capitals with which the ground is littered. Behind the portico is the

rest of the amphitheater. On the right is the Nile, with the beginning

of the date palm forest which borders the river and the ruins of the

city. Fellah are squatting in front of the portico; on the left, French

engineers are busy drawing the ruins." (Comments by Jomard in Vol.4 of Description de l'Egypte.)

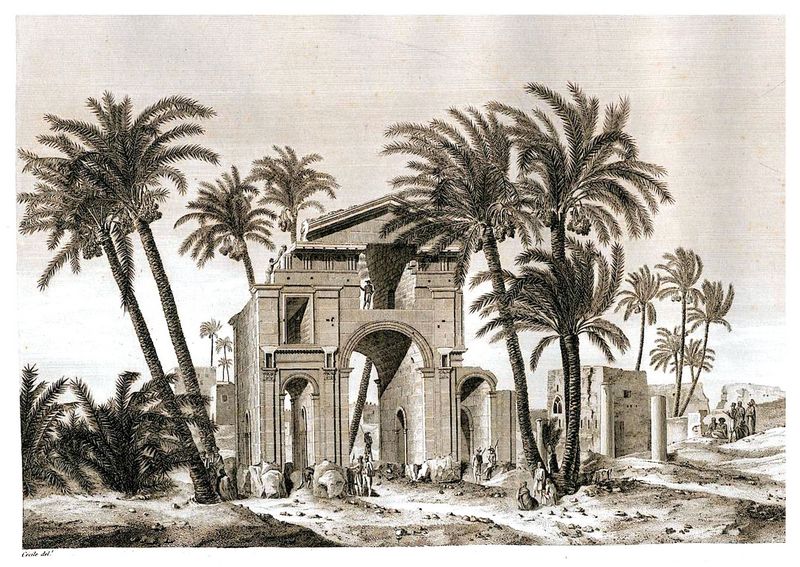

Fig.3: View of the Arc de Triomphe in Antinoe. (From Description de l'Egypte vol.4, 1817, plate 57; drawn by Cecile.)

"This monument is the best preserved of

all those in the city. The building is not missing any part that could

make its restoration doubtful. In front of the small Corinthian

pilasters, there were granite columns, which are entirely missing; only

the pedestals remain in place, and they are very ruined, as we see in

the engraving. In front of the triumphal arch, we can see the village

of Cheykh A'bâdeh; between the houses and the monument, there are

granite columns still standing. The date palms, which are in large

numbers around the building, contribute to making this viewpoint one of

the most picturesque of the ruins of Antinoé. Here and there, we see

inhabitants of the village, attentively considering the French

engineers and artists busy designing the triumphal arch." (Comments by Jomard in Vol.4 of Description de l'Egypte.)

The

next day, at eleven o'clock, we found ourselves between Antinoe and

Hermopolis. I was not very curious to visit Antinoe (plate 42-2); I had seen

monuments from the century of Hadrian, and what he had built in Egypt

could not have (p.147) anything spicy or new for me, but I longed to go

to Hermopolis, where I knew that there was a famous portico; also what

was my satisfaction when Desaix said to me: We are going to take three

hundred men of cavalry, and we will run to Achmounin, while the

infantry will go to Melaui.

Approaching the eminence on which

the portico is built, I saw it take shape on the horizon, and unfold

gigantic shapes: we crossed the Abou-Assi canal, and soon after,

through mountains of debris, we reached this beautiful monument, a

remains of the greatest antiquity (plate 11).

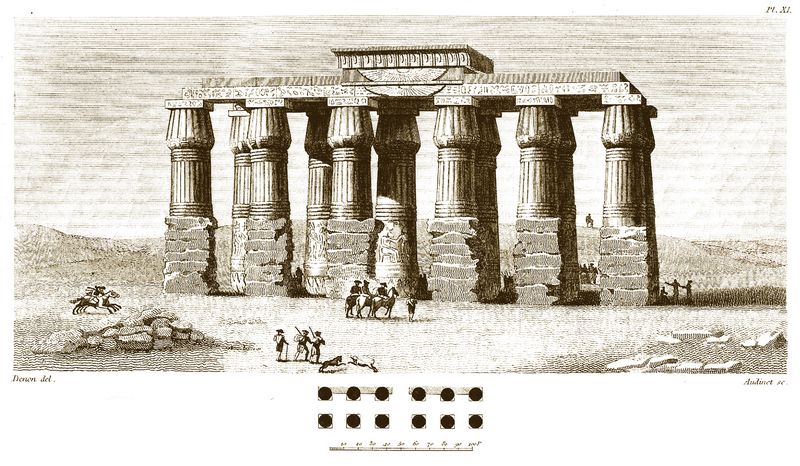

"Ruins

of the temple of Hermopolis or the great city of Mercury, capital of

the thirty-fifth nome, built by Ishmun, son of Misraim, some distance

from the Nile, very close to a large town called Ashmunein, and not far

from Melaui. To give an idea of the colossal proportions of this

building, it is enough to say that the diameter of the columns is 8

feet 10 inches, their spacing equal; that of the two middle columns, in

which the door was included, is 12; which gives 120 feet of width to

the portico: it is 60 feet high."

"The architrave is made up of

five stones 22 feet long, the frieze the same; the only stone remaining

from the cornice is 34 feet; These details can help us judge both the

ability that the Egyptians had to raise enormous masses, and the

magnificence of the materials they used. These stones are made of

sandstone which has the fineness of marble; they are only linked by the

perfection of their foundations: with regard to the plan of the temple,

no tearing can account for its enclosure and its nave; the second row

of columns was engaged up to the height of the door, the rest was up to

date: it is believed that what immediately followed was not yet the

nave or the consecration of the temple, but an enclosure or sort of

court which preceded it. What authorizes us to adopt this opinion is

that the frieze and the cornice had the same decoration on this side,

and the same projection as on the side of the entrance facade."

"The

time of day, and this particularity, made me choose this side to make

the drawing that I give here, where we can notice the tearing of the

engagement of the columns, and that of the door; the column shafts seem

to represent bundles, and the bottom the foot of the lotus plant at the

root. The capital has nothing analogous to any other known capital, but

is equivalent, in terms of gravity in Egyptian architecture, to the

Doric capital of Greek architecture, and we can say that this one is

richer than the other. All the other members have their equivalent in

all the other orders: on the astragalus of one and the other side of

the portico, and under the ceiling between the two middle columns, are

winged globes, emblems repeated there the same place in all Egyptian

temples. The hieroglyphs which are on the slabs which crown the

capitals are all the same, and all the ceilings are decorated with a

meander formed of stars painted aurora color on a blue background. The

plan of the portico is placed below the view." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

I

sighed with happiness: it was, so to speak, the first product of all

the advances I had made; it was the first fruit of my labors; excepting

the pyramids, it was the first monument which was for me a type of

ancient Egyptian architecture, the first stones which had preserved

their original destination, which, without mixture and alteration, have

been waiting for me there for four thousand years to give me an immense

idea of the arts and their perfection in this country. A peasant who

comes out of the cottages of his hamlet and is first placed in front of

such a building would believe that there is a large gap between him and

the beings who built it: without having any idea of architecture, he

would say: This is the house of a God; a man would not dare to live

there. Were it the Egyptians who invented and perfected such a great

and beautiful art? this is why it is difficult to pronounce: but what I

could not doubt from the first moment that I saw this building, was

that the Greeks had invented nothing and done nothing of greater

character. The first idea that came to disturb my enjoyment was that I

was going to leave this great object, that my moments were numbered,

and that drawing only (p.148) time and great talent; I lacked both; but

if I did not dare to put my hand to work, I did not dare to leave

without taking with me some drawing, and I only set to work sincerely

wishing that another would be happier that I could one day do what I

was going to sketch.

If sometimes drawing gives a large aspect

to small things, it always diminishes large ones; the capitals, which

appear heavy, the thinned bases, which are bizarre in the design, have

through their mass something imposing which stops criticism: here we

dare not adopt nor reject; but what must be admired is the beauty of

the main lines, the perfection of the device, the use of ornaments,

which create richness up close, without harming the simplicity which

produces the great. The immense number of hieroglyphs which cover all

parts of this building not only have no relief, but do not cut any

line, disappearing twenty paces away, and leaving the architecture with

all its gravity. The engraving, more than the description, will give a

precise idea of what is preserved from this building; the explanation

of the print and the plan will give all the dimensions that I was able

to obtain.

Among the mounds, two hundred toises from the

portico, we see half-buried enormous sections of stones, and

substructures, which appear to be those of a building to which granite

columns belonged, buried, and which barely we can distinguish on the

surface of the ground: further away, still on the rubble of the great

Hermopolis, is built a mosque, where there are a number of Cipolin

marble columns, of mediocre size, and all retouched by the Arabs; then

comes the large village of Achmounin, populated by around five thousand

inhabitants, for whom we were as strange a curiosity as their temple

had been for us.

We came to sleep at Melaui (p.149) ,

half a league from Achmounin. But I hear the reader say to me: What!

you are already leaving Hermopolis, after having tired me with long

descriptions of monuments, and you pass quickly when you might interest

me; who is pressing you? who worries you? are you not with an educated

general who loves the arts? have you not three hundred men with you?

All this is true; but such are the circumstances of a journey, and such

is the fate of the traveler: the general, very well intentioned, but

whose curiosity is soon satisfied, says to the designer: Three hundred

men have been on horseback for ten hours, I have to house them, they

have to make soup before going to bed. The designer understands this

all the better because he is also very tired, because he is perhaps

very hungry, because he bivouacs every night, because he spends twelve

to sixteen hours a day on horseback, and because the desert has torn

his eyelids, and his burning and painful eyes can only see through a

veil of blood.

Chapter

30: Continuation of the Description of Upper Egypt. - Melaui

- Bénéadi. - Siouth. - Tombs of Lycopolis. (p.149)

Melaui

is taller and even prettier than Mynyeh; the streets are straight, its

bazard very well built; and there is a spacious Mamluk house which

would be easy to fortify.

We had returned late; I had lost time

going through the town and looking for my neighborhood: I was lodged

outside the walls, and in front of a pretty house which seemed quite

comfortable: the owner, well-off, was sitting in front of the door; he

showed me that he had made General Belliard (p.150) sleep in a room,

and that I would find a place there too; I had been sleeping outside

for some time; I was tempted. Barely asleep, I am awakened by an

agitation which I take for an inflammatory fever; struggling with pain

and sleep; every minute, passing from the terror of a serious illness

to the collapse of weariness; ready to faint, I hear my companion who

says to me, half asleep, I am very unwell; I answer him, I can't take

it anymore: this dialogue completely wakes us up; we get up, we leave

the room, and, in the light of the moon, we find ourselves red,

swollen, unrecognizable. We did not know what to think of our state,

when, wide awake, we realize that we have become the prey of all kinds

of filthy animals.

The houses of Upper Egypt are vast dovecotes

in which the owner reserves a single room; he lives there with what

hens and chickens he has, and all the devouring insects he and his

animals produce: the search for his insects keeps him busy during the

day; the hardness of his brave skin, the night, their bite; also our

host, who in good faith believed he would do wonders, had no idea of

our escape. We got rid of the hungriest of our guests as best we could,

promising ourselves never to accept such hospitality. On the 23rd, we

continued to follow the Mamluks: they were still four leagues away; we

could gain nothing from them: they devastated as much as they could the

country they left between us. Towards the evening we saw a deputation

arrive with flags as a sign of alliance; they were Christians from whom

they had asked a contribution of a hundred camels; and, these

unfortunate people not having been able to give them to them, they had

killed sixty of their number; such a procedure having irritated the

Christians, (p.151) they had for their part killed eight Mamluks, whose

heads they offered to bring us: they all spoke at once, repeated the

same expressions a hundred times; but fortunately for our ears the

audience took place in a field of alfalfa, which offered refreshment to

the deputation, who began to eat grass as if it were a delicious dish

which one fears losing the opportunity to enjoy. to eat plenty. Without

dismounting, I also began to draw a deputy as he had just interrupted

his speech.

We came to sleep at Elgansanier, where we were fairly well accommodated in a santon's tomb.

On

the 24th (Dec. 1798), we were marching on Mont-Falut, when someone came

to tell us that the Mamluks were in Bénéadi, where we ran to look for

them. Electrified by everything around me, my heart beat with joy

every time the Mamluks were mentioned, without thinking that I was

there without animosity or rancor against them; that, since they had

never damaged the antiquities, I had nothing to reproach them with;

that, if the land we tread was ill-gotten for them, it was not up to us

to find it evil; and that at least several centuries of possession

establish their rights: but the preparations for a battle present so

many movements, form the whole of such a large picture, the results are

of such importance for those who engage in it, that they leave little

room for moral reflections; it is then only a question of success: it

is a game of such great interest that we want to win when we play.

We

arrived at Bénéadi, and our hope was disappointed again this time: we

found only Arabs there, whom our cavalry chased into the desert.

Bénéadi is a rich village half a league long, advantageously situated

for the caravan trade of Darfur; possessing an abundant territory, its

population has always been large enough to (p.152) find itself able to

come to terms with the Mamluks, and not let itself be ransomed by them.

It seemed to us that it was also necessary to procrastinate for the

moment, especially since the friendly advances that were made to us had

something that resembled conditions: we judged that it was necessary to

conceal the insolence of these procedures. under the guise of

cordiality. Surrounded by Arabs from whom they fear nothing, whose

needs they provide, and whom they can therefore dispose of, the

inhabitants of Bénéadi have an influence in the province which made

them embarrassing for any government; they came to meet us, they led us

back beyond their territory, without either of us being tempted to

spend the night together. We came to sleep at Bcnisanet.

On

the 25th, before arriving at Siouth, we found a large bridge, a lock,

and a levee to retain the waters of the Mil after the flood; these Arab

works, undoubtedly done according to ancient errors, are as useful as

they are well understood; In all, it seemed to me that the distribution

of water in Upper Egypt was done with more intelligence than in the

Lower, and by simpler means.

Siouth is a large, well-populated

city, on the site, to all appearances, of Licopolis or the city of the

Wolf. Why the city of the Wolf in a country where there are no wolves,

since they are a northern animal? Was this a cult borrowed from the

Greeks? and the Latins, who transmitted this name to us in centuries

when there was little attention to natural history, did they make any

difference between the chakal and the wolf? There are no antiquities

found in the town; but the Libyan chain, at the foot of which it is

built, offers such a large quantity of tombs that it is not possible to

doubt that it occupies the territory of an ancient great city. We

arrived at one o'clock in the afternoon; there were provisions to take

for the army, sick people to send to the ambulance, (p.153) boats and

provisions, which the Mamluks had not been able to take, of which it

was necessary to take possession: it was resolved to to sleep. I began

by making a drawing of the modern Siouth, half a league from the

Libyque range.

I quickly ran to visit her; I was so eager to

touch an Egyptian mountain! I saw two chains from Cairo without having

been able to risk climbing any of them: I found this one as I had

anticipated, a ruin of nature, formed of horizontal and regular layers

of limestone, more or less soft, more or less white, interspersed with

large nippled and concentric pebbles, which seem to be the cores or

bones of this long chain, supporting its existence, and suspending its

total destruction: this dissolution takes place daily by the impression

of the saline air which penetrates every part of the surface of the

limestone, decomposes it, and causes it, so to speak, to flow in

streams of sand, which first pile up near the rock, then are rolled

away by the winds , and step by step change the villages and fertile

fields into sad deserts. The rocks are nearly a quarter of a league

from Siouth; in this space is a pretty house of the kiachef who managed

for Soliman-bey. The rocks are hollowed out by innumerable tombs, more

or less large, decorated with more or less magnificence; this

magnificence can leave no doubt about the ancient proximity of a large

city: I drew one of the main of these monuments (plate 12-1), and the

interior plan.

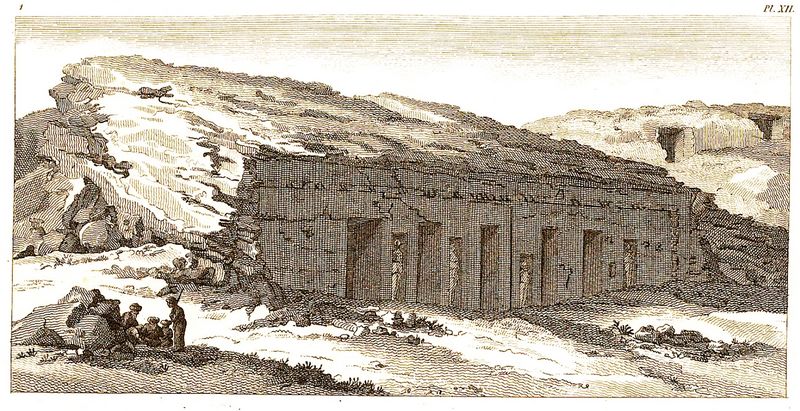

"No.

1.—Tomb of Lycopolis. It is one of the most considerable and best

preserved of those dug in the mountain near Siuth; the plan below shows

the interior and the distribution: the kind of peristyle which serves

as an entrance is, like the rest, cut and dug without masonry directly

into the rock; The missing parts were repaired with a stucco covering

which is still very well preserved. Firstly, its only ornament is a

torus which borders a low arch; but, from there and to the end of the

last chamber, everything is covered with hieroglyphs, and the ceilings

with sculpted and painted ornaments: on the facing of the doors there

are large figures which are repeated on the thickness of the jamb. I

saw no trace of hinges or other closures: the upper part of the door is

wider than the bottom; It is only at the third floor that we arrive at

the back room, where the main sarcophagus was undoubtedly; the ground

was searched almost everywhere." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Fig.4: Details of Tombs of Lycopolis.(Description de l'Egypte, vol. 4, 1817, Plates 46 and 47, drawn by Cecile.

Plate 46, fig.10: View of a tomb with reliefs of hieroglyphs and standing figures on the outside portal.

Plate 47, figs.2 and 4-7: Plans and sections of tombs.

Plate 47, figs.10 and 11: Bas-reliefs with hieroglyphic texts located in the doorways of two tombs.

All

the interior courts of these caves are covered with hieroglyphics; it

would take months to read them, if we knew the language [2]; it would take

years to copy them: what I was able to see with the little daylight

that enters through the first door, is that all the ornaments the

Greeks used in their architecture, all the meanders, the windings, and

what we commonly call the Greeks, are here executed with exquisite

taste and delicacy. If such (p.154) excavation is a single operation,

as the regularity of its plan would seem to indicate, it was a great

undertaking to make a tomb: but it is believed that it served in

perpetuity to an entire family, to an entire race; that people came

there to pay some worship to the dead: because, if we had never thought

of entering these monuments, what purpose would these decorations so

sought after, these inscriptions that we would never have read, this

splendor have been used? ruinous, secret, and lost? At various times or

festivals of the year, each time some new burials were added, some

funeral functions were undoubtedly celebrated there where the

magnificence of the ceremonies was added to the splendor of the place;

which is all the more probable since the richness of the interior

decorations are in striking contrast with the simplicity of the

exterior, which is completely raw rock, as can be seen in the view

that I made.

I found one with a simple room, which served

for an innumerable number of tombs taken in order in the rocks; it had

been thoroughly excavated to remove mummies: I still found some

fragments there, like linen, hands, heads, scattered bones. Besides

these main caves, there are so many small ones that the whole mountain

has become a cavernous and sonorous body. Further away, to the south,

we find the remains of large quarries, whose cavities are supported by

pilasters: part of these quarries was inhabited by solitary piles;

through the rocks, in these vast retreats, they joined to the austere

aspect of the desert that of a river which in its majestic course

spread abundance on its banks.

It was the emblem of their life;

before their retirement, troubles, riches, agitations; and since then,

calm and contemplative enjoyments: mute nature imitated the silence to

which they had condemned themselves; the constant and august splendor

of the Egyptian sky commands eternal admiration with severity; the

awakening of the day is not rejoiced by the cries of joy, the leaping

of animals; no bird's song celebrates the return of the sun; (p.155)

Talouette, who cheers up, animates our guerets, in these scorching

climates, shouts, calls, but never sings either his loves or his

happiness; the serious and superb nature seems to inspire only the deep

feeling of humble recognition: finally the cenobite's cave seems to

have been placed here by the order and choice of God himself;

everything that should animate nature shares with him his sad and

amazed meditation on this Providence, eternal distributor of eternal

benefits.

Small niches, stucco coverings, and some paintings in

red, representing crosses, inscriptions, which I believed to be in the

Coptic language, are the testimonies and the only remains of the

habitation of these austere cenobites in these austere cells. In the

season in which we saw them, nothing was comparable to the greenery of

all the hues which carpeted the banks of the Nile as far as the eye

could extend: carried along by curiosity, I had come so far that

I could no longer go to the neighborhood.

Leaving a big

city is always embarrassing for an army. The next day we set out before

daylight: all our guides were attached to the same division; and,

leaving ours to wander at random, we spent part of the morning

searching anxiously, and gathering ourselves with difficulty. We

followed all the windings of the Abou-Assi canal, which is the last in

Upper Egypt, and as considerable as an arm of the Nile could be; it

shares with this river the diameter of the valley, which on this day

did not seem to me to be more than a league, but cultivated with more

care and intelligence than anything we had seen until then; paths were

traced there which showed us that with very little cost we could make

excellent and eternal ones in a climate where it neither rains nor

freezes.

Every half league we found cisterns, with a small

hospitable monument to give water (p.156) to the passerby and his

horse: I drew one of the most considerable of these small philanthropic

establishments, as pleasant as they were useful, which characterize

Arab charity. Towards the middle of the day, we approached the desert,

where I found three new objects: the doum palm, which resembles in its

leaf the racket palm, which we know, and which does not, like the date

palm, a single stem, but from eight to fifteen; its woody fruit is

attached in groups to the end of the main branches, from which the

tufts which form the foliage of the tree originate; it is triangular in

shape and the size of an egg; its first envelope is spongy, and is

eaten like carob; its flavor is better, and approaches the taste of

gingerbread; under this covering is a hard, stringy bark like that of

the coconut, to which it resembles more than any other fruit; but it

absolutely lacks this fine woody part; its gelatinous part is

tasteless: it becomes very hard; we make rosary beads from it which

take the dye and the poll.

I also saw a charming little bird,

which based on its shape and habits I must place in the class of

flycatchers; he captured these insects at every moment with admirable

skill: thanks to the apathy of the Turks, all the birds among them are

familiar; the Turks like nothing, but do not disturb anything: the

color of the bird in question is green, clear, and brilliant; the

golden head, as well as the upper part of the wings; its long, black,

and pointed beak; and it has a feather on its tail half an inch longer

than the others: its size is that of the small titmouse. A little

further away, I saw swallows in the desert, as light gray as the sand

on which they fly; These do not emigrate, or go to similar climates,

because we never see them in Europe of this color: they are of the

cul-blanc species.

After thirteen hours of walking, we came to

sleep at Gamerissiem, (p.157) unfortunately for this village; because

the cries of the women soon made us understand that our soldiers,

taking advantage of the shadows of the night, despite their weariness,

were spending superfluous forces, and, under the pretext of looking for

provisions, were in fact snatching away what they did not need. :

robbed, dishonored, pushed to the limit, the inhabitants fell on the

patrols which were sent to defend them, and the patrols, attacked by

the furious inhabitants, killed them, for lack of understanding and

being able to explain themselves. . . O war, how brilliant you are in

history! but seen up close, how hideous you become, when it no longer

hides the horror of your details! On the 27th, we followed the desert,

which was bordered by a series of villages. Despite the cold we

experienced at night, the heat of the day and the products of the earth

warned us that we were approaching the tropic; the barley was ripe, the

wheat was in grain, and the melons, planted in the open field, were

already in production. flowers. We came to bivouac in a wood near

Narcette.

Footnotes:

1.

[Editor's note:] Antinoe was visited and drawn by other artists in

the French Egyptian Expedition (see figs.2 and 3 above, from Desc. de l'Egypte, vol.4,

1817). The site contains ruins from the 18th and 19th Dynasties, as

well as Ptolemaic structures including the triumphal arch (fig.2), and later,

Coptic monasteries and churches. A series of mummy portraits are

discussed in the monograph Les Portraits d'Antinoe,

by E. Gayet from the Musee Guimet in Paris, published by Librairie

Hachette in Paris; and temples of Isis and other deities from the

period of Hadrian are covered in Gayet's Antinoe et Les Sepultures de Thais et Serapion (Societie Francaise d'Editions d'Arte, 1902).

2.

[Editor's note:] Denon's observation on the Egyptian hieroglyphs and

their still unknown language, written in 1798, is 24 years earlier than

their decipherment by Jean-Francois Champollion, who using the

Rosetta stone (found in 1799 by French soldiers digging fortifications)

and other inscriptions, recognized that the ancient language used in

the hieroglyphs was revealed through the Coptic language and Demotic

script (see J.-F. Champollion, Lettre à M. Dacier relative à l'alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques, Paris, 1822).

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|