| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Voyage in Lower and Upper Egypt, during the Campaigns of General Bonaparte. Vivant Denon | | | | |

|

Vol. 1, Chapters 12-13

Chapter 12: Bogaze. - Alluvial deposits of the Nile. - Suppliers. - Tallien. - Intercepted correspondences, etc. (p.56)

Our

position had entirely changed: in the possibility of being attacked, we

were obliged to make defensive preparations; we fortified the entrance

to the Nile, we established a battery on one of the islands, we visited

all the points.

In one of our reconnaissances we returned to the

bogaze or bar of the Nile: it was at that time almost at its greatest

height; and we are able to see the efforts of its weight against the

waves of the sea, which in this season are pushed twelve hours of each

day by the north wind in the opposite direction to the course of the

river: it results from this ( p.57) fights a ridge of sand, which rises

with time, becomes an island which shares the course of the river, and

forms two mouths which each have their breakers; the eddy of these

breakers brings to the shore part of the sand that the current had

carried away, and, through this alluvium, the two mouths close little

by little until one of them prevails over the the other, the less

strong, becomes obstructed and becomes dry land with the island; and at

the remaining mouth another bulge soon reforms, an island, two new

mouths, etc. etc. Is this not how we can most naturally account for the

ancient geography of the mouths of the Nile, explain the journey of

Menelaus in Homer, the change of the Delta, whose replacement could

first have been a gulf, then a beach, then a cultivated land, covered

with superb cities and rich harvests, cut by canals, which, drying or

intelligently watering the soil, carried abundance over the entire

surface of this new country. time, the scourges of revolutions, and

their disastrous results, points of drying out will have manifested

themselves:; parts will have been abandoned, others will have become

saline; lakes will have been formed, destroyed, and reproduced with new

forms; the obstructed channels will have changed course, will have been

lost; and today, in our uncertain research, we ask where were the

mouths of Canopus, Bolbitine, Berenice, etc.

The first

plants that grow on the alluvium are three to four species of soda: the

sands pile up against these plants; they rise again on the pile: their

withering is a fertilizer which causes the pine nuts to grow; these

rushes further raise the ground and consolidate it: the date tree

appears, which, by its shade, preserves the humidity there, and brings

abundance, as can be seen in the surroundings of the castle of Racid,

which, in the time of Selim, had its right cannon at sea, and which

(p.58) is now a league from the shore, surrounded by forests of palm

trees, under which grow other fruit trees, and all the vegetables of

the most abundant of our gardens.

During

this expedition I saw, at the mouth of the river, a number of pelicans

and jerboas. Observing the castle of Racid, I noticed that it had been

built from members of ancient buildings; that some of the stones of the

cannon embrasures were beautiful sandstone from Upper Egypt, still

covered with hieroglyphics. While visiting the underground passages, we

found a kind of store there, made up of abandoned weapons; they were

crossbows, bows and arrows, with helmets and swords in the shape of

those of the crusaders. While searching these stores, we dislodged bats

as big as pigeons: we killed several of them; they had all the shapes

of the flying fox.

Since the loss of our fleet, what troops

there were at Rosetta had been scattered into small garrisons in the

castles and batteries: we had been obliged to establish a caravan from

Alexandria to Rosetta via Aboukir and the desert, to maintain

communication between these two cities: soldiers were employed to

protect these caravans against the Arabs: there were too few left in

Rosetta for the service of the place, and the defense in the event of

attack; it was therefore a question of forming a militia from what

there were travelers, speculators, and useless, uncertain, wandering,

irresolute men, who arrived from Alexandria or who were already

returning from Cairo: these amphibians, corrupted by the Italian

countryside, having heard of the Egyptian harvests as the most abundant

in the universe, had thought that taking possession of such a country

was the ready-made fortune of those concerned; others, curious, jaded,

their minds fascinated by Savary's stories, had left Paris to come and

seek new pleasures in Cairo; others, speculators, to supply the army,

to (p.59) observe, bring in and sell at a high price what the colony

might lack; and yet the beys had taken away all that there was of money

and magnificence in Cairo; the people had completed the plundering of

the opulent houses before our entry into this city; Bonaparte did not

want suppliers, and the merchant fleet found itself blocked by the

English: all these circumstances cast a dark veil over Egypt for all

these travelers, surprised to find themselves captive, disappointed in

their projects, and obliged to contribute to the defense and

organization of an establishment which no longer sees anything other

than the fortune and glory of the nation in general: they wrote sad

stories in France, which the English intercepted, and which contributed

to deceiving them about our situation.

The English, happy to

believe that we were dying of hunger, sent back our prisoners to us, to

hasten the time of our destruction. They printed in their gazettes that

half of our army was in the hospital, that half of the other half was

obliged to lead the rest who were blind; while, however, Upper Egypt

provided us in abundance with the best wheat, and Lower Egypt with the

finest rice; that the country's sugar cost half as much as in France;

that innumerable herds of buffalo, oxen, sheep and goats, both farmers

and pastoral Arabs, provided abundantly for new consumption at the very

moment of the invasion, which assured us abundance and superfluity for

the future: while, for the luxury of our tables, we could add all

species of poultry, fish, game, vegetables and fruits. However, this is

what Egypt offered in terms of essential objects to these detractors,

who needed gold to repair the abuse they had made of it; and who,

finding none, no longer saw around them only burning sand, perpetual

sun, fleas and cousins, dogs: who prevented them from sleeping,

intractable husbands, and veiled women showing them only eternal

throats.

p.60) But let us abandon to the wind this cloud of

butterflies which always flock where a first light shines: let us see

our triumphs and peace reopen the gate of Alexandria, bring there wise

and industrious farmers, useful traders, settlers finally , who,

without being frightened by the fact that Africa does not resemble

Europe, will observe that in Egypt a man, for three sous, can have as

much as he needs for one day of the best rice in the world ; that part

of the land which has ceased to be flooded can be returned to

cultivation by watering, that windmills would raise it higher than the

pot mills used there, and which consume so many oxen , occupy so many

hands; that the Nile Islands and the greater part of the Delta are only

waiting for American settlers to produce the finest sugar canes on a

soil that will not devour men; as they approach Cairo and beyond, they

will see that they only need to improve to compete with all the indigo

and cotton plantations of all kinds; that by making a wise and sure

fortune, they will live under a pure and healthy sky, on the bank of a

river of an almost miraculous kind, and of which we cannot finish

numbering the advantages: they will see a new colony with cities all

built, skillful workers accustomed to toil and fully acclimatized, with

whom, in a few years, and with the help of the canals which are all

traced, they will create new provinces, the future abundance of which

will not be is not problematic, since modern industry will only restore

them to their former splendor.

With regard to our careless

soldiers, they mocked our sailors who had been beaten: imagined that

Mourat Bey had a white camel loaded with gold and diamonds; and there

was no longer any question but of Mourat-bey and his white camel. For

myself, I had (p.61) had Upper Egypt, and I postponed thinking about

our situation until my journey was over.

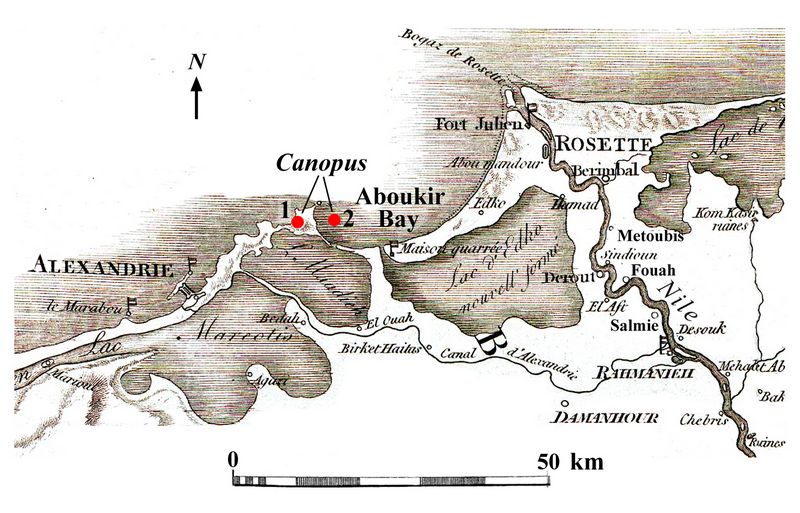

Chapter

13: Journey from Rosetta to Alexandria by Land. - Caravan. -

Aboukir Beach, seen after the Naval Battle. - Ruins of Canopus [1,2].

Our

tour in the Delta was delayed by the affairs which befell General

Menou: I resolved to use this delay to retrace my steps and retrace by

land the part of which I had only seen the coasts when coming from

Alexandria by sea; . I took advantage of a caravan to go and look for

the ruins of Canopus.

A number of local people had joined the

escort of this caravan: at dusk, when leaving the town it began to

develop on the smooth yellowish carpet of the sandy mounds which

surround Rosetta, it produced the most picturesque and imposing effect;

the groups of soldiers, those of merchants in their different costumes,

sixty loaded camels, as many Arab drivers, horses, donkeys,

pedestrians, some military instruments, offered the truth of one of the

most beautiful paintings of Benedetto, or of Salvator Rose. As soon as

we had descended the mounds and passed the palm trees, we entered, as

day expired, into a vast desert, where the horizontal line is broken

only by a few small brick monuments, which are intended to prevent the

traveler from getting lost. in space, and without which the smallest

error in the opening of the angle would cause it to lead by an extended

line to a goal far removed from that to which it was aiming. We walked,

in (p.62) the silence of the desert and the darkness, on a crust of

salt which consolidated the shifting sand a little: a detachment led

the way; then came the travelers, then the beasts of burden; another

military detachment secured the convoy against the Arab acrobats, who,

when they did not have the necessary forces to attack head-on,

sometimes came to kidnap the stragglers twenty paces from the caravan.

At

midnight we arrived at the seaside. The rising moon lit up a new scene;

four leagues of shore covered with our debris gave us the measure of

the loss we had suffered at the battle of Aboukir. The wandering Arabs,

to get a few nails or a few iron hoops, burned, all along the coast,

the masts, the carriages, the boats, still whole, manufactured at great

expense in our ports, and of which even the remains were still

treasures in places so stingy with such productions. The thieves fled

as we approached; All that remained were the corpses of the unfortunate

victims, who, carried and placed on soft sand with which they were

half-covered, had remained in pauses as sublime as they were

frightening.

The sight of these fatal objects had gradually

caused my soul to fall into a dark melancholy; I avoided these

frightening specters; and all those whom I met, by their varied

attitudes, arrested my gaze, and brought to my thoughts various

impressions: it had only been a few months since all these beings,

young, full of life, courage and hope , had been, by a noble effort,

torn away from the tears that I had seen shed, from the embraces of

their mothers, their sisters, their lovers, from the weak embraces of

their young children: all those to whom they were dear, I said to

myself, and who, yielding to their ardor, let them go away, still make

wishes for their success and their return; eager for news of their

triumph, they prepare parties for them, they content (p.63) the

moments, while the objects of their expectation lie on a foreign shore,

dried up by burning sand, their heads already white. . . . .What is

this truncated skeleton? is it you, intrepid Thévenard? impatient to

abandon shattered limbs to the helping iron, you only aspire to the

honor of dying at your post; an operation that is too slow tires your

restless ardor: you no longer have anything to expect from life, but

you can still give a useful order, and you fear being warned by death.

Another

specter succeeds; his arm envelops his head which sinks into the sand:

died in combat, remorse seems to survive your courageous end: do you

have any reproaches to make of yourself? your truncated limbs attest to

your courage; should you therefore be more than brave? Are the ruins

that the wave scatters around you piled up by your errors? and my soul,

moved by abandoning your remains, can I only give them sterile pity?

Who is this other one, sitting with his legs carried away? his

countenance seems to stop for a moment the death to which he is already

prey! it is you, without doubt, courageous Dupetithouars; receive the

tribute of the enthusiasm that you inspire in me: you die, but your

eyes when closing did not see your flag brought down, and your last

word was the order to the batteries that you commanded, to thunder on

the enemy of the fatherland: farewell; a tomb will not cover your

ashes, but the tears of the hero who misses you are the imperishable

trophy which will place your name in the temple of memory. What is this

in this calm attitude of the virtuous man, whose last action was

dictated by wisdom and duty? he still looks at the English fleet;

similar to Bayard, he wants to expire with his face turned towards the

enemy; his hand is extended towards tender and almost already destroyed

bones; However, I can distinguish a long neck and outstretched arms: it

is you, young hero, amiable Casablanca; it can only be (p.64) you;

death, inflexible death, has reunited you with your father, whom you

preferred to life; sensitive and respectable child, time promised you

glory; filial piety preferred death: receive our tears, the price of

your virtues.

The sun had chased away the shadows, and has not

yet seen the dark tint of my thoughts dissipated; However, the caravan

stopped and informed me that we were on the edge of the lake which

separates the desert plain from the peninsula at the end of which

Aboukir is built. This vast and deep lake is the ancient Canopite

mouth, which the Nile abandoned, and of which the sea, entering it

without obstacle, has by its weight pushed back the banks and widened

the bed: this ever-increasing evil threatens to destroy the the isthmus

which attaches Aboukir to the mainland, and on which flows the canal

which carries the waters to Alexandria. The Arab princes attempted to

build a dike, which was never united, or which, too weak, gave way to

the efforts of the wave, pushed during part of the year by the north

winds; only two piers remain of this dike on the respective banks. The

topographical plan of this little-known part of Egypt, and always

poorly traced on all maps, would provide the means to reason

effectively about the dangers which can result from the movement of the

sea, and to provide the necessary remedies for safety. of the important

canal which brought the waters of the Nile to Alexandria.

The

difficult embarkation on the Madié canal made this short journey almost

as long as the rest of the route. I drew it. On the other bank we found

the first works of a battery which we erected to protect this means of

communication, which the presence of the enemy made uncertain without

this precaution. We had barely passed when we had proof of it; for an

English brig and a viso, coming to disturb our march, fired seven or

eight (p.65) cannon shots at us; our silence made them believe that we

had nothing to answer them; consequently, a few hours later we saw

twelve boats detached from the English squadron, and the two vessels of

the morning which were coming at full sail towards our works. We

thought they were going to attempt a descent; but they were content to

anchor near the battery, and, when night came, to cannonade us: we

waited for the moon; and as soon as she had assured us of their

position, we began to respond to them in a manner apparently so

advantageous, that at the fourth cannon shot they cut the cables, left

their anchor, and disappeared.

After crossing the mouth of the

lake, following two sinuses bordered by sandy mounds, I finally arrived

at the suburb of Aboukir, which closely resembles the town, from which

it is separated by a space of one hundred and fifty paces: the two

together can be composed of forty to fifty bad huts in ruins, which cut

the peninsula into two parts, at the end of which the castle is built:

this fortress has some appearance from a distance; but the bastions

would collapse at the third blow from the culverines which are on the

ramparts, where they seem less aimed at than forgotten; there is a

bronze one fifteen feet long, carrying a fifty-pound ball. It was

necessary to throw down part of the batteries to form with the rubble a

platform solid enough to place four of our 36 cannons: this precaution

did not seem to me to be of much use, the buildings and boats likely to

carry heavy cannon to beat the walls unable to approach this promontory

because of the reefs and rocks which crown it. A hostile descent would

not take place there; and, once carried out, the castle could not hold,

and could not even serve as accommodation or stores, unless lines were

built in front to (p.66) defend the approach; but in all it seemed to

me that it would be preferable to destroy the castle, to fill in the

fountains, thus sparing a garrison, useless when there is no enemy, and

which must always be blocked or a prisoner of war from the moment he

was able to make a descent.

I made a bird's eye view of the peninsula.

I

found in the doorway of the castle four large stones of dark green

porphyry, and two long stones of the most compact statuary granite; at

the second door, I found, with four other stones, a member of a Doric

entablature, bearing triglyphs of great proportion and beautiful

execution: these fragments, with some traces of substructions at the

point of the rock, are the only antiquities that I was able to discover

at Aboukir, the location of which could never have changed, since the

ground is a limestone platform which rises above the sea, and is not

attached to the land only by an isthmus too narrow for a considerable

city to have been built there: it could therefore never have been other

than the fort or the castle at sea of Canopus or Heraclea, which Strabo

places there or near there. I had passed in front of fountains half a

mile before arriving at Aboukir; their construction was praised to me:

I returned there; I only found three square wells of Arab manufacture;

they are surrounded by heights which certainly contain ruins against

which are piled up an immense quantity of shards of terracotta pots,

mixed with the desert sands carried by the wind. Are these buried Arab

towers? Were these pot factories? are these the ruins of Heraclea? a

few pieces of granite on the platform, of the greatest eminence, would

make me prefer the latter opinion.

The next day, I followed,

with a detachment, the west coast, (p.67) questioning all the windings

and the smallest eminences; because, in Lower Egypt, they contain all

the antiquities, which are almost always their core. After three

quarters of an hour of walking, I found at the bottom of the second

cove a small jetty formed of colossal debris: what pleasure I felt when

first seeing a fragment of a hand, including the first phalanx, of

fourteen inches, belonged to a figure of thirty-six feet in proportion!

The granite, the work, and the style of this piece left me in no doubt

that it dates back to ancient Egyptian times; from the movement of this

hand, from some other debris which surrounds it, and from the sole

habit of seeing Egyptian figures, whose pose offers so little variety,

we can recognize in this fragment an Isis holding a nilometer: it it

would be easy to take this piece; but if moved it would lose almost all

its value. Near there several members of architecture attest by their

size that they belonged to a large and beautiful building of Doric

order: the waves have covered and struck these debris for many

centuries without having disfigured them: it seems that it is the fate

attached to all Egyptian monuments to equally resist men and time.

Further

into the sea, we see mixed with the fragments of the colossus that of a

sphinx, whose head and front legs are truncated, as far as the

madrepores and small shells have allowed me to judge; it is of a Greek

style and chisel and is not made of granite, but of a sandstone

resembling white marble, and of a transparency that I have only ever

seen in Egypt in this material; it was thirteen to fourteen feet in

proportion. At some distance, in the middle of the remains of

entablatures similar to those I have described, is another figure of

Isis, sufficiently preserved so that we can recognize its pose; its

legs are broken, but the piece is next to it. This figure (p.68) is in

granite, and has ten feet of proportion. All this debris seems to have

been placed there to form a pier, and to serve as a breaker in front of

a destroyed building; but which, judging by its substructions, can only

be the remains of a bath taken on the sea, and of which the cut rock

still traces the plan. The part that does not cover the sea retains

water conduits built of bricks, and covered in cement and pozzolan. All

this not having enough projection to make a drawing which was a view, I

traced a kind of figurative plan (plate 5) which will give the image of

the ruins and the fragments which I have just described.

Four

hundred toises from there, returning inland, still stretching towards

Alexandria, we find several structures built of bricks; and, although

we cannot make a case for it, we judge, by a few fragments of careful

constructions, that they were part of important buildings. Near there

we find several Corinthian capitals in marble, too crude to be

measured, but which must have belonged to bases of the same material,

and which gave the column twenty inches in diameter. Further on, a

large quantity of sections of fluted pink granite columns, all of the

same size, of the same material, worked with the same care, are the

indisputable ruins of a large and superb temple of the Doric order.

According to what Strabo has transmitted to us about this part of

Egypt, according to everything that I have just described, and in

particular these last fragments, I had no doubt left that these were

the ruins of Canopus, and those of its temple built by the Greeks,

whose cult rivaled that of Lampsacus: this miraculous temple where old

people find youth again; and the sick, health. The bath of which I gave

a view (plate 5) was perhaps one of the means that the priests used to

perform these miracles.

(p.69) The ground

has preserved nothing of the ancient Canopite pleasure; a few eminences

of sand and brick ruins, large square granite stones, without

hieroglyphs or shapes which attest to what type of building and to what

century they belonged, finally small valleys, as arid as the mounds

from which they are formed, are all that remains of this city, once so

delicious, and which now offers only a sad and wild appearance. It is

true that the canal of which Strabo speaks, which communicated from

Alexandria to Eleusine, and which by a branch arrived at Canopus, and

brought freshness there, has disappeared in such a way that we cannot

distinguish the trace of it, nor even conceive the possibility of its

existence: there remains water in the surrounding area only in a few

wells or cisterns, so narrow and so obscure that we can measure neither

their dimensions nor their depth; however, they still contain water:

finally this city, which brought together all the delights, where all

the voluptuous flocked, is now nothing more than a desert crossed by a

few jackals and Bedomns: I did not find there any last; but I saw a

jackal, which I would have taken for a dog, if I had not had the time

to very clearly examine its pointed nose and erect ears, its tail,

longer, trailing, and furnished with hair like that of the fox, to

which it resembles much more than the wolf, although the jackal is

regarded as the African wolf.

Unable to take advantage of the

escort that had accompanied me, I took the road to Aboukir: there I

found dispatches for the general in chief; a detachment was going to be

sent to carry them: I could not help myself from the pleasure that the

opportunity offered me to leave such a sad place. During my stay there,

I was never able to shake the thought that this castle was a state

prison to which I was relegated; this cramped rock, continually beaten

by the waves, the unwelcome noise (p.70) which results from it, the

whistling of the winds, the whiteness of the ground which tires the

sight, everything in this sad abode afflicts and withers the soul: by

leaving it, it seemed to me that I was escaping all the torments

of a tyrannical captivity.

I set out on a dark night; I was left

walking in the sea, scratching myself in the thickets, and sometimes

falling into the debris scattered on the shore; but at three o'clock in

the morning I arrived at Rosette, and I went to rest voluptuously, I

won't say in my bed, I hadn't seen one since I left France, but in a

cool room, on a proper mat.

Footnotes:

1.

[Editor's note] Canopus was an ancient Egyptian town located on the

Abuquir peninsula on the western bank at the mouth of the westernmost

branch of the Nile Delta. Herodotus (5th c. BC) refers to Canopus as an

ancient port; it was the principal port in Egypt for Greek trade before

the foundation of Alexandria. Eastern parts of Canopus, and the ancient port town of Heracleion-Thonis, are today

submerged in the sea, and have been located by underwater

archaeologists, while the western parts of Canopus (including the bath ruins found by Denon) are buried beneath the modern

coastal city of Abu Qir.

Canopus was the site of a temple to

the Egyptian god Serapis built by king Ptolemy III Euergetes. In 239

BC, Ptolemy III passed the "Decree of Canopus" which conferred various

new titles on the king and his consort, Berenice. Examples of this

decree inscribed in both hieroglyphic and demotic as well as Greek,

like the Rosetta Stone, provided keys to decipherment of the ancient

Egyptian language.

2. Description and maps of underwater sites at Canopus by Franck Goddio (Underwater

Archaeology in the Canopic Region in Egypt: The Topography and

Excavation of Heracleion-Thonis and East Canopus (1996 - 2006), Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology, University of Oxford, 2007 ).

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|