| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Voyage in Lower and Upper Egypt, during the Campaigns of General Bonaparte. Vivant Denon | | | | |

|

Vol. 1, Chapter 17

Arrival in Cairo.—Visit to the Pyramids.—House of Mourut Bey. (p.91)

More

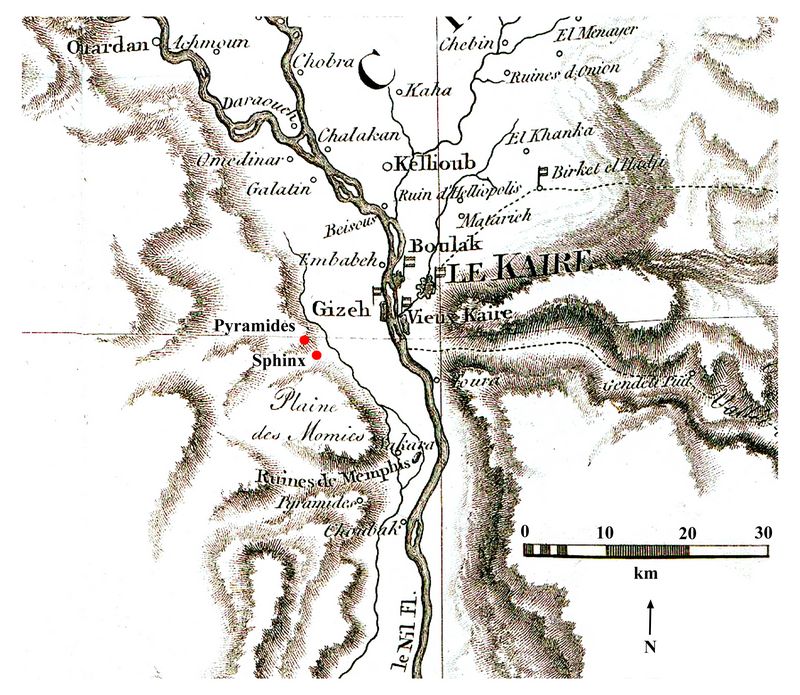

than ten leagues from Cairo we discovered the tip of the pyramids which

sees the horizon; soon after we saw Mount Karam, and opposite, the

chain which separates Egypt from Libya, and prevents the sands of the

desert from coming to devour the banks of the Nile: in this perpetual

combat between this beneficial river and this destructive scourge we

often see this arid wave submerge the countryside, changing their

abundance into sterility, chasing the inhabitant from his house,

covering the walls, and letting only a few tops of palm trees escape,

the last witnesses of its vegetative existence, which adds to the sad

aspect of the desert the distressing thought of destruction.

I

found myself happy to see mountains again, to see monuments whose era,

whose object of construction, were also lost in the night of centuries:

my soul was moved by the great spectacle of these great objects; I

regretted seeing the night spread its veils over this picture as

imposing to the eyes as to the imagination; it hid my view (p.92) of

the tip of the Delta, where, among the number of vast projects in

Egypt, there was talk of building a new capital. At the first ray of

daylight, I returned to greet the pyramids; I made several drawings of

them: I took pleasure on the surface of the Nile, at its highest point

of elevation, in seeing the villages slide in front of these monuments,

and composing at any moment landscapes of which they were always the

object and the 'interest. I would have liked to show them with this

fine and transparent color that they get from the immense volume of air

that surrounds them; it is a particularity which gives them over all

other monuments the extraordinary superiority of their elevation; the

great distance from which they can be seen makes them appear

diaphanous, with the bluish tone of the sky, and gives them the finish

and purity of the angles that the centuries have devoured.

Around

nine o'clock, the sound of the cannon announced to us both Cairo and

the festival of the first of the year which was celebrated there: we

saw innumerable minarets surrounding Mount Katam, and emerging from the

gardens which border the Nile; old Cairo, Boulac, Roda, grouping with

the city, add to it the charm of greenery, giving it in this aspect

grandeur, beauties, and even amenities: but soon the illusion

disappears; each object returning, so to speak, to its place, we only

see a bunch of villages, which have been gathered there we don't know

why, moving them away from a beautiful river to bring them closer to a

barren rock.

As soon as I arrived at the general-in-chief's

house, I learned that a detachment of two hundred men was leaving that

very hour to protect the curious who had not yet seen the pyramids: I

groaned at not having known some hours ago this expedition, and I

believed that seeing such important objects without having provided

oneself with what could put one in a position to observe them

fruitfully, was only giving in to vain curiosity; I was moreover so

tired from the two journeys that I had just made, that all my (p.93)

muscles advised me against undertaking a third, and I considered it

prudent to postpone my curiosity until the moment when astronomers had

to go and make their observations in these famous places.

Leaving

the table the general said: We can only go to the pyramids with an

escort, and we cannot often send a detachment of two hundred men there.

This training that certain minds exert on the minds of others destroyed

all my reasoning; this training which had brought me to Egypt made me

leave for the pyramids, and, without returning home, I made my way to

old Cairo; On the way I joined comrades with whom I crossed the Nile.

We arrived at Giza after dark: I did not know where I would sleep; but

determined to bivouac, it was good luck which seemed to me to be part

of the enchantment to suddenly find myself on beautiful velvet couches,

in a room where the scent of orange blossom was brought to us by a

zephyr refreshed under cradles of thick trees: I went down into the

garden, which, in the light of the moon, seemed to me worthy of

Savary's descriptions. This house was the pleasure house of Mourat-bey:

I had heard him depreciate, I only saw it after the passage of a

victorious army: and yet I could not help feeling that, if the we do

not want to destroy anything by useless comparisons, oriental

enjoyments have their merit, and we cannot refuse our senses to the

voluptuous abandonment that they inspire.

These are neither our

long and sumptuous French avenues, nor the winding paths of the English

gardens, those gardens where, as a price for the exercise they require,

we obtain both hunger and health. In the East, vain exercise is

excluded from the number of pleasures; From the middle of a group of

sycamores, whose lowered branches provide more than cool shade, we

enter under . tents or kiosks open at will on thickets of orange trees

and jasmines: let us add to this enjoyments, which are (p.94) still

imperfectly known to us, but whose voluptuousness we can conceive: such

is, for example, the charm one must feel in being served by young

slaves in whom the flexibility of form is combined with a gentle and

caressing expression; there, on soft and immense carpets, covered with

tiles, nonchalantly lying near a favorite beauty, intoxicated with

desires, with health, with the smoke of perfumes, and with sorbet,

presented by a hand that softness has consecrated throughout time to

love; near a young favorite, whose gloomy modesty resembles innocence,

embarrassment resembles timidity, the terror of novelty resembles the

turmoil of feeling, and whose languid eyes, moist with voluptuousness,

seem to announce happiness and no obedience, the burning African is

undoubtedly allowed to believe himself as happy as us. In love, isn't

everything else convention?

In truth, we have created yet

another happiness with her; but is this not at the expense of reality?

Ah! yes: happiness is always found near nature; it exists everywhere

where it is beautiful, under a sycamore in Egypt as in the gardens of

Trianon, with a Nubian as with a Françoise; and the grace which is born

from the flexibility of movements, from the harmonious agreement of a

perfect whole, grace, this divine portion, is the same in the entire

world, it is the property of nature equally distributed to all beings

who enjoy the fullness of their existence, whatever the climate in

which they were born. It is not here the happiness of a Mamluk that I

wanted to paint; monstrosities must always be kept out of his

paintings; and, if we sometimes allow ourselves to make a sketch of it,

it must be a caricature which inspires contempt and disgust.

The

officer who commanded the escort happened to be a friend of mine; he

designated me among the small number of those who were to enter the

pyramids: there were three hundred of us. The next morning we (p.95)

looked for each other, we waited for each other; we left late, as

always happens in large associations. We crossed inland by watering

canals; after many journeys in the cultivated country, we arrived at

noon on the edge of the desert, half a league from the pyramids: I had

made several sketches of their approaches on the way, and a view of the

house of Mourat-bey. We had barely left the boats when we found

ourselves in sand: we climbed up to the plateau on which these

monuments stand; when we approach these colossi, their angular and

inclined shapes lower them and hide them from the eye; moreover, as

everything that is regular is only small or large in comparison, these

masses eclipse all surrounding objects, and yet they do not equal in

extent a mountain (the only large thing that our mind quite naturally

compares them), we are quite surprised to feel the decline of the first

impression that they had made from afar; but as soon as we come to

measure this gigantic production of art by a known scale, it regains

all its immensity: in fact a hundred people who were at its opening

when I arrived there seemed so small to me that they did not seem to me

more men.

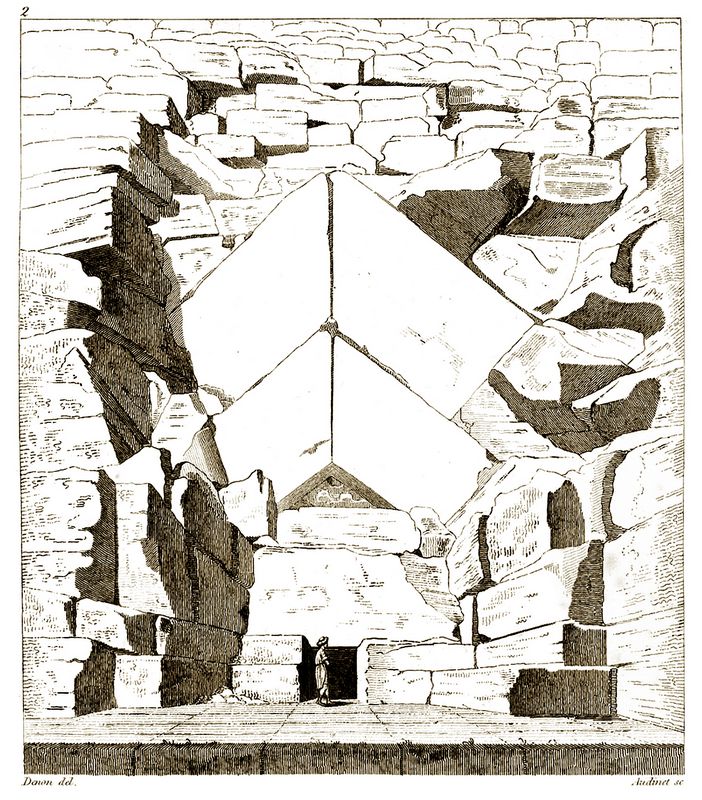

"No.

2.—Entrance to the galleries of the pyramid of Cheops; each faithfully

drawn stone can give an idea of the structure of this part of the

building, which was covered with a facing similar to the general

surface area of the entire monument. It is to citizen Ftigo, member of

the Cairo institute, that I owe this interesting plate; returning from

the expedition, he was kind enough to allow me to take from his

interesting portfolio several objects, such as this one, and costumes

which I will announce by their number." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

I believe that to give, in painting as in drawing, an

idea of the dimensions of these buildings, it would be necessary to

represent in the right proportion on the same level as the building a

religious ceremony analogous to their ancient uses. These monuments,

devoid of a living scale, or accompanied only by a few figures on the

front of the painting, lose both the effect of their proportions and

the impression they should make. We have an example of comparison in

Europe in the church of St. Peter in Rome, of which the harmony of

proportions, or rather the crossing of lines, conceals the grandeur, of

which we only get a clear idea when (p .96) lowering its view on a few

celebrants who are going to say mass followed by a troop of faithful,

we believe we see a group of puppets wanting to play Athalie on the

theater of Versailles: another rapprochement of these two buildings is

that There were only priestly despotic governments that could dare to

undertake to raise them, and stupidly fanatical peoples who had to lend

themselves to their execution.

But, to talk about what they are,

let us first climb onto a mound of rubble and sand, which are perhaps

the remains of the excavation of the first of these buildings that we

encounter, and which are used today to arrive at the opening through

which one can enter; this opening, found approximately sixty feet from

the base, was masked by the general covering, which served as a third

and final enclosure of the silent recess which this monument contained:

there the first gallery immediately begins; it heads towards the center

and the base of the building; the rubble, which was poorly extracted,

or which, by the slope, naturally fell back into this gallery, joined

to the sand which the north wind engulfs there every day, and which

nothing removes, have cluttered this first passage, and make it very

inconvenient to cross. Arriving at the end, we encounter two blocks of

granite, which were a second partition of this mysterious conduit: this

obstacle undoubtedly surprised those who attempted this excavation;

their operations have become uncertain; they started in the

construction massif; they made an unsuccessful breakthrough, retraced

their steps, circled around the two blocks, surmounted them, and

discovered a second gallery, ascending, and of such steepness that it

was necessary to make cuts on the ground to make the climb possible.

When

through this gallery we have reached a kind of landing, we find a hole,

which we agree to call the well, and the mouth of one (p.97) of a

horizontal gallery, which leads to a room, known under the name of the

queen's room, without ornaments, cornice, or any inscription: returning

to the landing, one climbs into the large gallery, which leads to a

second landing, on which was the third and last fence, the most

complicated in its construction, the one which could give the most idea

of the importance that the Egyptians placed on the inviolability of

their tomb. Then comes the royal chamber, containing the sarcophagus:

this small sanctuary, the object of a building so monstrous, so

colossal in comparison with everything colossal that men have made.

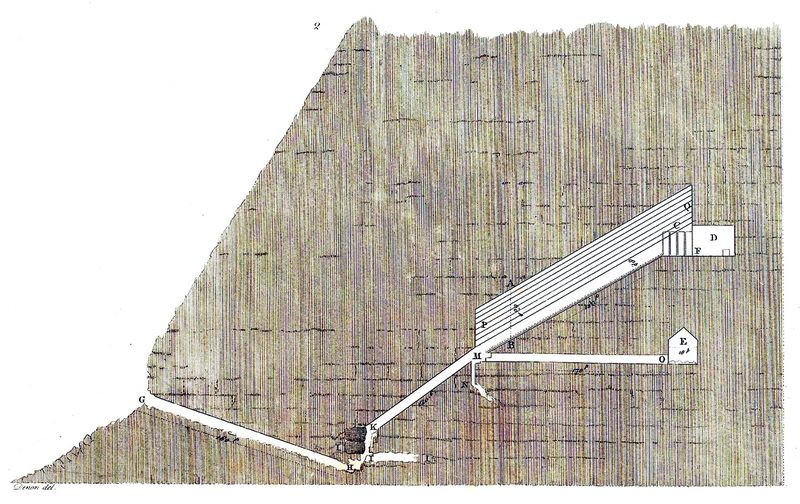

"No.

2.—Section of the open pyramid, called Cheops, from which we can gain

an idea of the galleries which lead to the two sepulchral chambers,

which appear to have been the only objects for which these kinds of

buildings were constructed."

"G, the entrance to the first

gallery, which was covered by the general facing, and which apparently

had some particularity at this location which could have revealed this

entrance when an excavation was attempted. Gallery G to H goes towards

the center and to the base of the building; it is sixty-five steps

long, which we are obliged to do in such an inconvenient manner, that

we must only estimate them at one hundred and sixty feet: arrived at H,

the uncertainty, caused by the meeting two blocks of granite L,

misplaced the excavation, and attempted one directed horizontally into

the mass of the factory; this excavation abandoned, we returned to

point I; and, searching around the two blocks up to twenty-two feet

going up, we found the entrance to the ascending ramp K, which, up to

M, has a hundred vino-t feet: we climb this narrow and rapid gallery

using notches made in the ground, and his arms against the sides of

this narrow gallery; the factory is made of limestone, bonded with

brick cement. Arrived at the top of this ramp, we find a new landing M,

approximately fifteen feet square; to the right is an opening N, which

we agree to call the Well, and which from the irregularity of its

orifice can be believed to be another attempt at excavation; it would

take time, light, and ropes to accurately ascertain its depth and

direction; we hear that it soon ceases to be perpendicular by the.

noise made by the fall of a stone: this well is two feet by 18 inches

in diameter; it would be necessary to carry out an excavation to be

able to venture any conjectures on this excavation; to the right of

this hole, is a horizontal gallery O, of HO feet, heading towards the

center of the building, at the end of which is the entrance to a

so-called queen's bedroom, E: its shape is a long square 18 feet 2

inches by 15 feet 8 inches; its height is uncertain, because an eager

curiosity caused it to jostle the ground, and dig one of the lateral

parts, and (p.5) the rubble of all these violations was left on the

spot. The upper part has the shape of a roughly equilateral corner

roof; no ornament, no hieroglyph, no vestige of sarcophagus: a fine

limestone, and linked with a refined device, makes all the ornament of

this room (See even pi., the plan and section of this room, No. 4 and

5J." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

Plate 6-3: Architectural features of the galleries in the Pyramid of Cheops

.

"What was this room intended for? was it to put a body? In

this case, the pyramid, built with the intention of placing two, was

not closed at a single time; in case of waiting, and this second burial

was actually that of the queen, the two blocks of granite, of which I

have already spoken, and which are at the entrance to the two inclined

galleries, were therefore reserved to definitively close the 'opening

of the two bedrooms, and adjacent galleries."

"Let

us retrace our steps to the platform of well M, where, by climbing a

few feet, we find ourselves at the bottom of a large and magnificent

ramp, P Q, 180 feet long, also heading towards the center of the

editor; its width is 6 feet 5 inches in which must include two parapets

of 1.9 inches in diameter, pierced, in spaces of 3 feet six inches,

with holes 22 long, 3 wide. This ramp was undoubtedly intended to mount

the sarcophagus; the holes had served to ensure, by some machine, the

movement of this mass on such an inclined plane; the same machine had

undoubtedly required cuts above the side part of each of these holes,

which were then repaired by patching. This gallery gradually closes up

to its ceiling with eight recesses 6 feet high; which, joined to 12

that there is ground up to the first platebau. of, gives 60 feet of key

to this strange vault (See its section, Plate 6 No.x. Arrived above,

with the help of fairly regular but modern notches, we find a small

platform, then a kind of granite chest C, whose lateral parts,

supported by the general mass of the building, were intended to receive

in the void they left blocks of the same material, which, harrowed in

protruding and re-entrant grooves, were to hide and defend the door

forever of the main burial (See letter CT No. 1 and 8J. It undoubtedly

required immense work to first build and then destroy this part of the

building; here, superstitious enthusiasm found itself struggling with

ardent avarice, and the latter prevailed."

"After the

destruction of thirteen feet of granite, a square door F, 3 feet 3

inches, was discovered, which is the entrance to the main room D,

square in shape, 32 feet by 16 feet long. wide, and 18 feet high - the

door is at the corner of the long side as in the room below. Towards

the back, on the right as you enter, is an isolated sarcophagus, 6 feet

1 L inches long by 3 feet wide, and 3 feet 1 inch 6 lines of elevation.

When we say that this tomb is made of a single piece of granite, that

this chamber is only one, chest of the same material, with a

half-polished of a device precious enough so that it has no necessity

of cement in all its apparatus, we will have described this strange

monument, and given the idea of the austerity of its magnificence. The

tomb is open and empty, without any vestige of its cover remaining;.

the only deterioration in this entire room is the attempted excavation

at one of the corners, and two small, approximately round holes, at the

height of the support, to which curious people have attached too much

importance. This is where the journey ends, as it seems that this was

the goal of this immense enterprise, where men seem to have wanted to

measure themselves with nature." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

If

we consider the object of the construction of the pyramids, the mass of

pride which made them undertake seems to exceed that of their physical

dimension; and from this moment we do not know what should be more

surprising: the tyrannical madness which dared to order the execution,

or the stupid obedience of the people who were willing to lend their

arms to such constructions: finally the report the most worthy for

humanity under which we can consider these buildings, is that in

raising them men wanted to compete with nature in immensity and

eternity, and that they did so successfully, since the The mountains

which surround these monuments of their audacity are lower and even

less preserved.

Citizen

Grosbert, engineer, who stayed at the Pyramids, and who made a plan

(Plates 59 and 60) in relief, which can be seen with interest in the

National Garden

of Plants, and an explanation in a book entitled, Description of the

Pyramids of Gizéh, from the city of Cairo and its surroundings, gives

Cheops 728 feet of base, and estimates its height at 448 feet, counting

the base by the proportional average of the length, of the stones, and

the height by the addition of the measurement of each of the various

bases. According to the calculations of Citizen Grosbert and Mr.

Maillet, the sepulchral chamber is 160 feet above the floor of the

pyramid.

The base of the pyramid called Chephren is estimated

by the same author to be 655 feet, and its elevation to be 398 feet;

its roof, of which there is still something in its upper part, is a

coating made up of gypsum, sand, and pebbles. The Mycerinus, or third

pyramid, says citizen Grosbert, has a base of 280 feet and an elevation

of 162: I will refer my readers to this writer for the plans and

details that I did not have time to take. and that his knowledge in

this part has enabled him to give with the accuracy that deserves the

importance of these buildings, and the interest that they inspire.

We only had two hours to be at the pyramids: I

spent one and a half visiting the interior of the only one that was

open; I had gathered all my faculties to realize what I had seen; I had

drawn and measured as much as the help of a single king's foot could

have allowed me; I had filled my head: I hoped to bring back many

things; and, when I reported all my observations the next day, I was

left with a volume of questions to ask. I returned from my trip

exhausted both mentally and physically, and feeling my curiosity about

the pyramids more irritated than it was before having taken my steps

there.

I only had time to observe the sphinx, which deserves to

be drawn with the most scrupulous care, and which has never been drawn

in this way. Although its proportions are colossal, the contours which

are preserved are as supple as they are pure: the expression of the

head is soft, graceful and tranquil, the character is African: but the

mouth, whose lips are thick, has a softness in the movement and a

finesse of execution truly admirable; it is flesh and life. When such a

monument was made, the art was undoubtedly at a high degree of

perfection; if this head lacks what we are agreed to call style, that

is to say the straight and proud forms that the Greeks gave to their

divinities, we have not done justice nor to the simplicity nor the

grand and gentle passage of nature which we must admire in this figure;

In all, we have never been surprised by the size of this monument,

while the perfection of its execution is even more astonishing.

"No.

1.—-Profile of the Sphinx, which reflects its state of destruction, and

the character of this figure in the parts which have been preserved:

the living characters serve as a scale of proportion; the one who is

above the head, and who is helped by the hand, comes out of a narrow

excavation, ending in rubble, and which is only 9 feet deep. Notches

cut from space to space in the lateral parts of this excavation serve

as steps for going up and down this hole, the use of which has remained

in the night of mystery; the monument that we see behind is a kind of

tomb in the style of small pyramids.; but so degraded that it is

difficult to account for it other than by the existing form of its

ruin." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

I

had glimpsed tombs, small temples decorated with bas-reliefs and

statues, trenches in the rock which could have formed the pyramids and

given elegance to their mass; it seemed to me that there remained so

many objects of observation to be made, that it would have taken many

more sessions like this one to undertake to do something other than

sketches, and finally to dissipate the mysterious cloud which seems to

have everything veiled time these symbolic monuments.

We are

almost equally uncertain about the period when they were violated, and

the period in which they were built: the latter, already lost in the

night of centuries, opens an immense space to the annals of the arts;

and, in this respect, we cannot admire too much the precision of the

apparatus (p.99) of the pyramids, and. the inalterability of their

form, of their construction, and in such immense dimensions, that we

can say of these gigantic monuments that they are the last link between

the colossi of art and those of nature.

Herodotus reports that he had

been told that the great pyramid, the one of which I have just spoken,

was the tomb of Cheopes; that the neighboring pyramid was that of his

brother Cephrenes who had succeeded him; that only that of Cheopes had

interior galleries; that a hundred thousand men had been busy twenty

years building it; that the work that this building had required had

made this prince odious to his people, and that, despite the chores

that he had demanded of his subjects, the mere expense of food for the

workers had risen so high that he had was forced to prostitute his

daughter to complete the monument; finally that, from the surplus of

what this prostitution had brought in, the princess had found enough to

build the small pyramid which is opposite, and which served as her

burial. Either the Egyptian princesses who prostituted themselves were

then paid very dearly, or filial love was carried to a high degree in

this daughter of Cheopes, since, in her enthusiasm, she had shown even

more devotion than was required by her father, and had collected enough

to build another pyramid for himself. How much work he did during his

life to ensure a place of rest after his death! It must also be said

that Cheopes, having closed the temples during his reign, had not found

after his death any panegyrists among the priest-historians of Egypt,

and that Herodotus, our first light on this country, had left himself

tell many fables by these priests.

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|