| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Voyage in Lower and Upper Egypt, during the Campaigns of General Bonaparte. Vivant Denon | | | | |

|

Vol. 1, Chapters 9-11

Chapter 9: Agricultural Arabs - Bedouin Arabs. (p.48)

By

observing the causes we are almost always less likely to complain about

the effects. Can we reproach the cultivating Arabs for being gloomy,

distrustful, avaricious, without care, without foresight for the

future, when we think that in addition to the vexation of the owner of

the land they cultivate, of the greedy bey , of the sheikh, of the

Mamluks, a wandering enemy, always armed, constantly waiting for the

moment to take away everything he dares to show that is superfluous?

The money that he can hide, and which represents all the enjoyments of

which he deprives himself, is therefore all that he can truly believe

is his; also the art of burying it is his main study: the bowels of the

earth do not reassure him: rubble, rags, all the livery of misery, it

is by only presenting these sad objects to view from his masters that

he hopes to shield this metal from their greed; it is important for him

to inspire pity: not to pity him would be to denounce him; worried

while amassing this dangerous money, troubled when he possesses it, his

life passes between the misfortune of not having any, or the terror of

seeing it taken away.

We had in truth driven out the Mamluks;

but, upon our arrival, experiencing all kinds of needs, by chasing them

away, had we not replaced them? and these Bedouin Arabs, poorly armed,

without resistance, having for rampart only shifting sands, of line

only space, of retreat only immensity, who will be able to defeat or

contain them? Will we try to seduce them by offering them land to

cultivate? but the peasants of Europe who become hunters cease to work

the land without return; and the Bedouin is the primitive hunter;

laziness and independence are the basis of his character; and to

satisfy and defend both, he (p.49) is constantly agitated, and allows

himself to be besieged and tyrannized by need. We can therefore offer

nothing to the Bedouins which could amount to the advantage of robbing

us; and this calculation is always the basis of their treaties.

Envy,

a fiend from which even the stay of need is not exempt, hovers still on

the burning sands of the desert. The Bedouins war with all the peoples

of the universe, only hating and envying the Bedouins who are not of

their horde; they engage in all wars, they move as soon as an internal

quarrel or a foreign enemy comes to disturb the rest of Egypt, and,

without attaching themselves to one or the other of the parties , they

take advantage of their quarrel to pound them both. When we went down

to Africa, they mingled among us, kidnapped our stragglers, and would

have plundered the Alexandrians if they had come to be beaten outside

their walls. Where there is booty, there is the enemy of the Bedouins:

always ready to negotiate, because there are gifts attached to the

stipulations, they only know necessity. Their cruelty, however, is not

at all atrocious: the prisoners they took from us,1 in retracing the

evils they had suffered in their captivity, considered them rather as a

continuation of the way of life of this nation than as a result of

barbarism; officers, who had been their prisoners, told me that the

work that had been required of them had not been excessive or cruel;

they obeyed the women, loaded and led the donkeys and camels; In truth,

it was necessary to camp and decamp at any time; the whole household

was packed up, and we were on the road in a quarter of an hour at most:

the rest of this household consisted of a grain and coffee grinder, an

iron plate for cooking pancakes, a large and a small coffee pot, a few

wineskins, a few grain bags, and the canvas of the tent which served as

an envelope for all this. A handful of roast corn and twelve dates were

the common ration for days of marching, and some (p.50) little water,

which, given its scarcity, had been used for everything before being

drunk; but these officers, not having had their souls blighted by any

ill treatment, they retained no bitter memory of an unfortunate

condition which they only saw themselves sharing.

Without

religious prejudice, without external worship, the Bedouins are

tolerant: a few revered customs serve as laws to them; their principles

resemble virtues which suffice for their partial associations, and for

their paternal government.

I must cite a feature of their

hospitality: an officer Francis had been the prisoner of an Arab leader

for several months; his camp surprised at night by our cavalry, he only

had time to escape; tents, herds, provisions, everything was taken. The

next day, wandering, isolated, without resources, he took a loaf of

bread from his clothes, and giving half to his prisoner, he said to

him: I do not know when we will eat another; but I will not be accused

of not having shared the last one with the friend I made. Can we hate

such a people, however fierce they may be? and what advantage does this

sobriety give over us compared to the needs we have made for ourselves?

how can such men be persuaded or reduced? will they not always have to

reproach us for sowing rich harvests on the tombs of their ancestors?

Chapter 10: Insurrections in the Delta. - Fire of Salmie -Egyptian Meal.

As

long as we had not been masters of Cairo, the inhabitants of the banks

of the Nile, regarding our existence as very precarious in Egypt, had

apparently submitted to our army during its passage; but, not doubting

(p.51) that it would soon melt before their invincible tyrants, they

had allowed themselves, either so that they would forgive them for

having submitted, or to give in to their spirit of plunder , to run and

shoot at the boats that we sent to the army, and at those which

returned from it: some boats were forced to backtrack, after having

received rifle shots for several leagues of the way, notably from the

inhabitants of the villages of Metoubis and Tfemi. An advisor and some

troops were sent against them: I was part of this expedition; the

instructions were peaceful; we accepted their submissions, and took

hostages. During the negotiations required by our treaty, I expressed

the views of Metoubis and Tfemi.

A few days later, another boat

left for Cairo: we heard no more of those who were on it; and it was

only through the people of the country that we knew that they had been

attacked beyond Fouah; that after having all been injured, their leaders

had thrown themselves into the water; that, left to the current, they

had failed; that when arrested and taken to Salmie, they were shot

there. General Menou felt obliged to make a great example. We therefore

appeared with two hundred men on a half-chebek and boats; we landed

half a league from Salmie; a detachment circled the village, another

followed the river bank; the third division, which was to complete the

circumvallation, remained engraved two leagues below. We found the

enemies on horseback, in battle, in front of the village; they attacked

us first, and charged even on bayonets: the main ones having been

killed at the first discharge, and seeing themselves surrounded, they

were soon in rout; the third division, which was to close the retreat,

not having arrived in time, the sheikh and all the combatants escaped.

The village was left to pillage for the rest of the day, and to fire.

as soon as night came: the flames and (p.52) cannon fire while the

darkness lasted warned ten leagues around that our vengeance had been

complete and terrible. I made a drawing of it in the light of the fire.

We

returned to Fouah, where we were received as victors who knew how to set

limits to their vengeance: all the sheikhs of the ancient province had

been summoned, and had assembled; They heard with respect and

resignation the manifesto which was read to them concerning the

expedition, and the bases on which the new organization of Salmie was

going to be established. A former sheikh was appointed in place of the

one whom the French had just dispossessed and proscribed; he was sent

to gather together the scattered inhabitants, and to bring a

deputation, which arrived on the third day. The detachment which had

led the old sheikh had been received with acclamation. The deputies

told us on arriving that they had recognized paternity in the hand that

had rested on them; that they saw clearly that we did not wish them any

harm, since we had only killed nine culprits, and burned only a quarter

of the village: they added that the fire had been extinguished, that

the house of the emigrant sheikh had been destroyed, and that they had

offered the rest of the chickens and geese to the soldiers who had come

to put an end to the remorse that had tormented them for three weeks.

We

established an ordinary post office in Salmie in agreement with the

neighboring districts, and we completed our expedition with a tour of

the department. In each village we were received in a more than feudal

manner; he was the principal personage of the country who received us,

and made the inhabitants pay our expenses. It was necessary to know

about the abuses before remedying them; seduced moreover by the ease

that chance offered us to observe the customs of a country whose morals

we were going to change, we let it happen again this time.

A

public house, which almost always had belonged to (p.53) Marmelouk,

former lord and master of the village, found itself in a moment

furnished, in the fashion of the country, with mats, carpets, and

cushions; a number of servants first brought fresh scented water, pipes

and coffee; half an hour later, a carpet was spread; all around we

formed a pile of three or four types of bread and cakes, the entire

center of which was covered with small dishes of fruit, jams, and dairy

products, most of them quite good, above all very fragrant. We seemed

to only enjoy it all; indeed in a few minutes this meal was finished:

but two hours later the same carpet was covered again with other breads

and immense dishes of rice in fatty broth and milk, poorly roasted

half-mutton, large quarters of calves , boiled heads of all these

animals, and sixty other dishes all piled on top of each other: these

were flavored stews, herbs, jellies, jams, and unprepared honey. No

seats, no plates, no spoons or forks, no cups or napkins; kneeling on

your heels, you take the rice with your fingers, you tear off the meat

with your nails, you dip the bread in the stews, and you wipe your

hands and lips with it; we drink water from the pot: the one who does

the honors always drinks first; he tastes the first of all dishes, less

to prove to you that you should not suspect him than to show you how

much he is concerned about your safety, and the importance he places on

your person. You are only presented with a napkin after dinner, when

they bring hand washing; then rose water is poured over the whole

person; then the pipe and the coffee.

When we had eaten, the

people of the second order of the country came to replace us, and were

themselves very quickly relieved by others: by principle of religion a

poor beggar was admitted, then the servants, finally all those who

wanted, up to until everything was eaten. If these meals lack

convenience and that elegance which whets (p.54) the appetite, we can

admire the abundance, the hospitable abandon, and the frugality of the

guests, which the number of dishes does not detract from. never more

than ten minutes at the table.

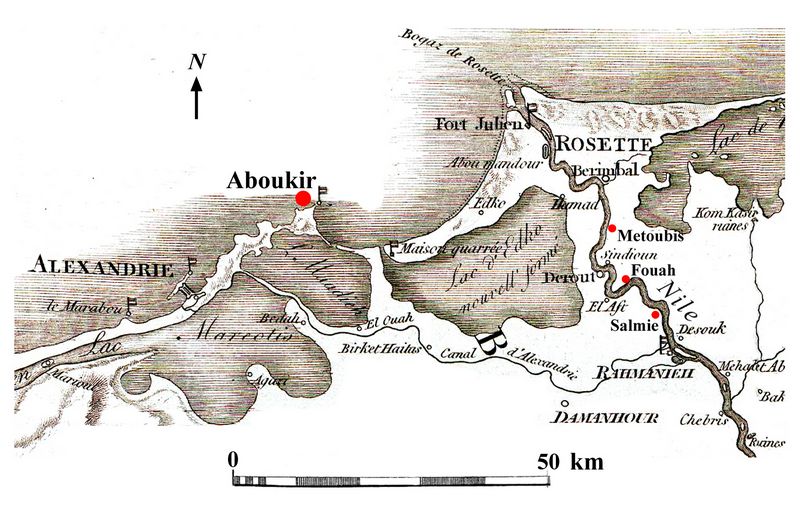

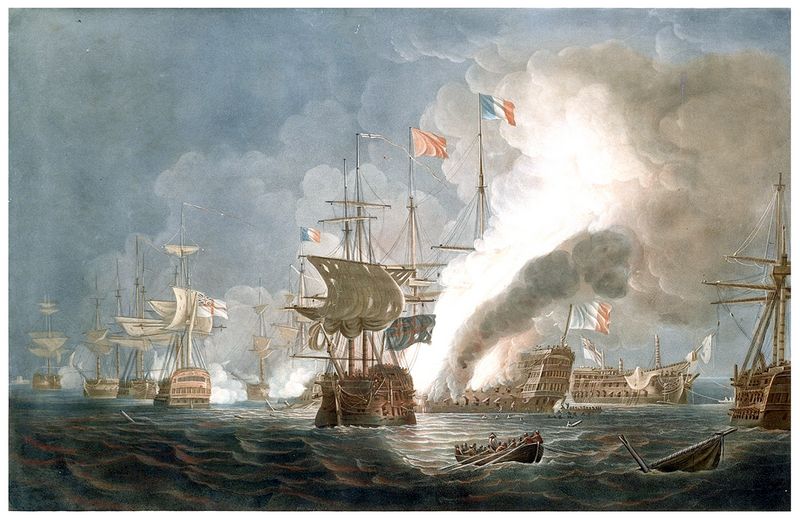

Chapter 11: Naval Battle of Aboukir. [1]

On

the morning of August 1, we were masters of Egypt, Corfu, and Malta;

thirteen ships of the line returned this possession contiguous to

France, and made it into one empire. England only cruised in the

Mediterranean with numerous fleets which could only obtain supplies

with immense difficulty and expense.

Bonaparte, feeling all the

advantage of this position, wanted, to preserve it, for our fleet to

enter the port of Alexandria; he had promised two thousand sequins to

anyone who provided the means: captains of merchant ships had, it was

said, found a pass in the old port; but the evil genius of France

advised and persuaded the admiral to embark at Aboukir, and to change

in one day the result of a long series of successes.

On the 1st,

in the afternoon, chance had led us to Abou-Mandour, a convent of which

I have already spoken, and which, from Rosette, is the end of a pretty

walk along the banks of the river: arrived at the tower which dominates

the monastery, we see twenty sails; arriving, getting into line, and

attacking, was the matter of a moment. The first cannon shot was heard

at five o'clock; soon the smoke hid the movements of the two armies

from us; but at night we were able to see a little better, without

however being able to realize what was happening. The danger we ran of

being carried off by the smallest body of Bedouins could not (p.55)

distract us from the eager attention excited in us by an event of so

great interest. The rolling and redoubled fire was perpetual; we could

not doubt that the combat was terrible, and sustained with equal

obstinacy. Returning to Rosette, we climbed onto the roofs of our

houses; around ten o'clock, a great light showed us a fire; a few

minutes later a terrible explosion was followed by a profound silence:

we had seen shooting from left to right at the flaming object, and, as

a result of reasoning, it seemed to us that it must have been ours who

had set the fire; the silence which followed must have been the result

of the retreat of the English, who alone could continue or cease the

combat, since they alone had the freedom of space. At eleven o'clock a

slow fire began again: at midnight the combat was again engaged; it

ceased at two o'clock in the morning: at daybreak I was at the advanced

posts, and, ten minutes later, the cannonade was re-established; at

nine o'clock another ship blew up; At ten o'clock four ships, the only

ones remaining intact, and which we recognized as French, crossed the

battlefield at full sail, of which they appeared to be masters, since

they were neither attacked nor followed. Such was the phantom produced

by the enthusiasm of hope

I spent my life at the Abou-Mandour

tower; I counted twenty-five vessels there, half of which were nothing

more than mutilated corpses, and the rest of which found it impossible

to maneuver to rescue them: three days we remained in this cruel

uncertainty. With my telescope in hand I drew the disasters, to see if

the next day would bring any change: we pushed back the evidence with

the hand of illusion; but the closed bogaze, and the communication from

Alexandria intercepted, told us that our existence was changed; that,

separated from the metropolis, we had become colonies, obliged until

peace to exist by our means: we finally learned that the English fleet

had (p.56) doubled our line, which had not been solid enough leaning

against the island which was to defend it; that the enemies, taking our

ships in a double line one after the other, this maneuver, which

invalidated all of our forces, had made half of them spectators of the

destruction of the other; that it was the Orient which had blown up at

ten o'clock; that it was the Hercules which had jumped the next day;

that those who commanded the ships the Guillaume Tell and the Généreux,

and the frigates the Diane and the Justice, seeing the others in the

power of the enemy, had taken advantage of the moment of his weariness

to escape his combined blows. We finally learned that August 1st had

broken this beautiful ensemble of our strength and our glory; that our

destroyed fleet had restored to our enemies the empire of the

Mediterranean, an empire that the incredible exploits of our land

armies had wrested from them, and that the mere existence of our ships

would have preserved us.

Footnotes:

1.

[Editor's note: ] The Battle of Aboukir Bay between the British and

French navies on August 1-3, 1798 concluded the naval campaign that

began with the sailing of the large French convoy from Toulon to

Alexandria, carrying an expeditionary force under Bonaparte. The

British fleet was led by Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson; they

decisively defeated the French under Vice-Admiral François-Paul Brueys

d'Aigalliers.

The French fleet had anchored in Aboukir Bay in

what was considered a formidable defensive position. On August 1, The

British fleet arrived off Egypt and Nelson ordered his ships to advance

on the French line and split into two divisions, with one passing

between the anchored French and the shore, while the other engaged the

seaward side of the French fleet. Trapped in a crossfire, the French

warships were battered into surrender during a fierce three-hour

battle. The French flagship Orient exploded, and only two ships of the

line and two frigates escaped from a total of 17 ships. The British

Royal Navy therebty gained the dominant position in the Mediterranean.

Their controlling force off the Syrian coast contributed to the French

defeat at the siege of Acre in 1799, resulting in Bonaparte's

abandonment of Egypt and return to Europe.

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|