| Southport : Original Sources in Exploration | | |

Voyage in Lower and Upper Egypt, during the Campaigns of General Bonaparte. Vivant Denon | | | | |

|

Vol. 1, Chapters 6-8

Chapter 6: March of the Army, from Alexandria to Cairo.- Trait of Jealousy. -Mirage. - Combat of Chebrise. (p.36)

Most

of the divisions, when they got off the ship, had only crossed

Alexandria to camp in the desert. It was necessary to take care also to

abandon Alexandria, this important point in history, where the

monuments of all eras, where the debris of the arts of so many nations

are piled up pell-mell, and where the ravages of wars, of centuries,

(p.37) and of a humid and saline climate, have brought more of change

and destruction than in any other part of Egypt.

Bonaparte, who

had seized Alexandria with the same rapidity as St. Louis had taken

Damietta, did not commit the same mistake: without giving the enemy

time to recognize himself, and his troops time to see the shortage of

Alexandria and its harsh territory, he ordered to put the divisions

into action as they landed, and, without giving them time to gather

information on the places they were going to occupy. An officer, among

others, said to his troop at the time of departure: My friends, you are

going to sleep in Bédah; you hear: in Bédah; it is not more difficult

than that: let us march, my friends, and the soldiers marched. It is

undoubtedly difficult to cite a more striking trait of naivety on the

one hand and confidence on the other: it is with this carefree courage

that we undertake what others dare not project, and that we performs

what seems inconceivable.

More

curious than surprised, they arrived at Bédah, which they believed to be

a built village, populated like ours; They only found a well filled

with stones, through which a little brackish and muddy water distilled;

drawn with goblets, it was distributed to them, like brandy, in small

rations. This is the first stage of our troops in another part of the

world, separated from their homeland by seas covered with enemies, and

by deserts a thousand times more formidable; and yet this strange

position does not dampen their courage or their cheerfulness.

If

we want to have the measure of the domestic despotism of the Orientals,

if we do not fear shuddering at the atrocity of jealousy, when it is

supported by a received prejudice, and when religion absolves us of its

outbursts, let we read the following anecdote.

On the second day

of our troops' march from Alexandria, some soldiers encountered, near

Bedah, in the desert, a young woman with a bloody face (p.38); She held

a small child in one hand, and the other stray hand went to meet the

object that could strike or guide her. Their curiosity is excited; they

called their guide, who also served as their interpreter; they

approach, they hear the sighs of a being whose organ of tears has been

torn away; a young woman, a child in the middle of a desert!

Astonished, curious, they question: they learn that the horrible

spectacle before their eyes is the result and the effect of a jealous

fury: it is not murmurs that the victim dares to express, but prayers

for the innocent who shares his misfortune, and who will perish from

misery and hunger. Our soldiers, moved with pity, immediately gave him

a part of their ration, forgetting their need in the face of a more

pressing need; they deprive themselves of a rare water of which they

are going to run out completely, when they see a furious man arrive,

who from afar, feasting his eyes on the spectacle of his vengeance,

followed these victims with his eyes; he runs to snatch from the hands

of this woman this bread, this water, this last source of life that

compassion has just granted to misfortune: Stop! he exclaims; she

failed in her honor, she tarnished mine; this child is my shame, he is

the son of crime. Our soldiers want to oppose his depriving her of the

help they have just given her; his jealousy is irritated by the fact

that the object of his fury becomes once again that of tenderness; he

draws a dagger, strikes the woman with a fatal blow; seizes the child,

kidnaps him, and crushes him on the ground; then, stupidly fierce, he

remains motionless, stares fixedly at those around him, and braves

their vengeance.

I inquired if there were repressive laws

against such atrocious abuse of authority; I was told that he had done

wrong to stab her, because if God had not wanted her to die, at the end

of forty days they could have received the unfortunate woman in a house

and fed her out of charity.

The Kléber division, commanded by

Dugua, had taken the route to (p.39) Rosette to protect the flotilla

which had entered the Nile. The army completed its march on June 6 and

7, via Birket and Damanhour: the Arabs attacked the outposts and

harassed the rest; death becomes the punishment of the dragger. Desaix

is about to be taken for remaining fifty steps behind the column; Le

Mireur, a distinguished officer, who, due to a melancholy distraction,

had not responded to the invitation that had been made to him to come

closer, was assassinated a hundred steps from the outposts;

Adjutant-General Galois is killed carrying an order from the

general-in-chief; Adjutant Delanau is taken prisoner a few steps from

the army while crossing a ravine: a price is put on his ransom; the

Arabs argue over the division of it, and, to end the dispute, blow out

the brains of this interesting young man.

The Mamluks had come

to meet the French army: the first time she saw them was near

Damanhour; they only recognized it, and this appearance, as well as the

insignificant combat of Chebrise, gave our soldiers their measure, and

took away from them that uncertain emotion which is reminiscent of

terror, and which always gives an unknown enemy. For their part, having

seen in our army only infantry, a sort of weapon for which they had

sovereign contempt, they took away the certainty of an easy victory,

and no longer tormented our march, already quite difficult by its

length, by the heat of the climate, and the sufferings of thirst and

hunger, to which we must also add the torments of a hope always

deceived and always reborn; in fact it was on piles of wheat that our

soldiers lacked bread, and with the image of a vast lake before their

eyes they were devoured by thirst. This torture of a new kind needs to

be explained, since it is the effect of an illusion which only takes

place in these regions: it is produced by the mirage of protruding

objects on the oblique rays of the sun refracted by the stiffness of

the burning earth (p.40); this phenomenon offers so much the image of

water that we are deceived the tenth time as well as the first; it

fuels a thirst that is all the more ardent because the moment when it

manifests itself is the hottest of the day. I thought that a drawing

would not give the idea, since it could only ever be the representation

of a resemblance; but, to supplement this, one must read a report made

at the Cairo institute, and inserted in the memoirs printed by Didot

the elder, in which citizen Monge described and analyzed this

phenomenon with sagacity and erudition which characterize this scholar.

The villages were deserted as the army approached, and the inhabitants took away everything that could have supplied them.

Watermelons

were the first relief that the soil of Egypt offered to our soldiers,

and this fruit was consecrated in their memory by gratitude. On

arriving at the Nile they threw themselves into it fully dressed to

quench their thirst from every pore.

When the army had passed

Rahmanieh, its marches on the banks of the river became less arduous.

We will not follow her to all her stations; we will only say that on

July 20 she came to sleep at Omm-el-Dinar; she left before daylight the

next day; after twelve hours of walking she found herself near Embabeh,

where the Mamluks were gathered; They had an entrenched camp there,

surrounded by a bad ditch, defended by thirty-eight pieces of cannon.

Chapter 7: Battle of the Pyramids.

As

soon as the enemies were discovered, the army was formed: when

Bonaparte had given his last orders, he said, pointing to the pyramids:

(p.41) Go, and think that from the top of these monuments forty

centuries are watching us . Desaix, who commanded the vanguard, had

passed the village; Reynier followed on his left; Dugua, Vial and Bon,

still on the left, formed a semi-circle approaching the Nile.

Mourat-bey, who came to recognize us, and who saw no cavalry, said that

he was going to cut us like pumpkins (this was his expression): as a

result the most considerable body of the Mamluks, which was in front of

Embabey, set off, and came to charge the Dugua division with a rapidity

which had barely given it time to form; she received them with

artillery fire which stopped them; and by one to the left they came

right up against the bayonets of the Desaix division; a heavy and

sustained file fire produced a second surprise: they were for a moment

without determination; then, suddenly wanting to turn the division,

they passed between that of Reynier and that of Desaix, and received

crossfire from both; which began their rout.

Having no longer any

plans, one part returned to Embabey, the other went to entrench itself

in a park planted with palm trees, which was to the west of the two

divisions, and from where they were sent to dislodge them by

skirmishers; they then took the road to the desert of the pyramids. It

was they who subsequently disputed with us for Upper Egypt. Meanwhile

the other divisions, approaching the village, found themselves in the

situation of being damaged by the artillery of the entrenched camp:

they resolved to attack it; two battalions were formed, drawn from the

Bon and Menou divisions, and commanded by generals Rampon and Marmont,

to march on the village, and turn it with the help of the ditch: the

Rampon battalion seemed easy to them to envelop and destroy ; he is

attacked by what remained of the Mamluks in the camp.

It was

there that the fire was the strongest and most deadly; they did not

understand our resistance (they have since said that they believed we

were linked together): in fact the best cavalry of the East, perhaps of

the whole world, came to break against a small body bristling with

bayonets; there were some who came to set their clothes on fire in the

fire of our musketry, and who, mortally wounded, burned in front of our

ranks. The rout became general: they wanted to return to their camp;

our soldiers followed them and entered pell-mell with them; their

cannons were taken; all the divisions which approached while

surrounding the village deprived them of all means of retreat; they

wanted to follow the Nile, a wall which reached it transversely stopped

them and pushed them back; then they threw themselves into the river to

join the corps of Ibrahim-bey, who had remained opposite to cover

Cairo: from then on it was no longer a fight, but a massacre; the enemy

seemed to march past to be shot, and only to escape the fire of our

battalions to fall prey to the waters.

In the midst of this carnage,

looking up, one could be struck by this sublime contrast offered by the

pure sky of this happy climate: a small number of French, under the

leadership of a hero, had just conquered part of the world ; an empire

had just changed masters; the pride of the Mamluks was finally

shattered against the bayonets of our infantry. In this great and

terrible scene, which was to have such important results, the dust and

smoke scarcely disturbed the lowest part of the atmosphere; the star of

the day rolling over a vast horizon peacefully ends its career: sublime

testimony to this immutable order of nature which obeys eternal decrees

in this silent calm which makes it even more imposing. This is what I

tried to depict in the drawing I made of this moment.

The official account of General Berthier, where the military movements

are

detailed in the most lucid and learned manner, will still serve as an

explanation of the plan of this battle, a plan which must acquire a

particular value by the corrections that Bonaparte himself was willing

to make in the disposition of the corps, and the determination of their

movements.

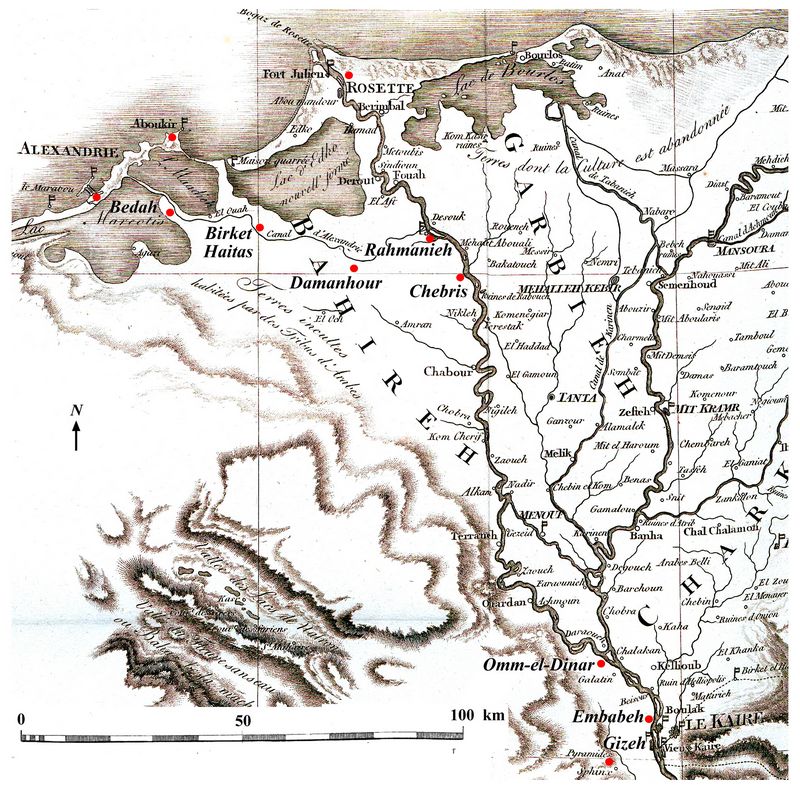

Chapter 8: Author's tour in the Delta.—Le Bogaze.—Rosette. (p.43)

General

Menou remained injured in Alexandria: he had to go and organize the

government in Rosetta (fig.4), and make a tour in the Delta. Before going to

Cairo, he had invited me to accompany him on this walk: I decided all

the more willingly to make this trip, as I thought in advance that it

could only be very interesting if that we would do it before that of

Upper Egypt; I was also accompanying a kind, educated man, and my

friend for a long time.

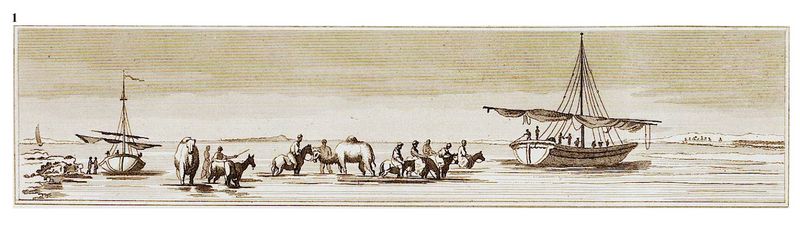

We embarked on an advice boat in the new

port of Alexandria; we maneuvered all day: but our captains, knowing

neither the currents, nor the breakers, nor the shallows of this port,

after having avoided the Pointe du Diamant, thought of stranding us at

the rock of Petit Pharillon, and brought us back to anchor at the

entrance to the port to leave the next day. I made the drawing of the

castle (plate 2, no.3), built on the island of Pharus, on the site of this famous

monument so useful and so magnificent, this wonder of the world, which,

after having taken the name of the island on which it had been raised ,

transmitted it to all monuments of this kind.

Plate 2, No. 3 (from Plate 2 by Vivant Denon, in vol.3) "The

great Pharillon, built at the end of a pier; a Turkish castle of some

appearance, more useful, in the state it is in, to house a garrison

than to defend the city. The rock in front is called the Diamond. It is

believed that it was there that the famous Lighthouse was built, one of

the wonders of the world: we can see no vestige of it; it is now

nothing more than a battered reef covered with the waves of all the

winds." (Comments by Vivant Denon in vol.2, Explanations of Plates.)

We reappeared the

next day under as bad auspices as the day before. We were barely a few

leagues out to sea when the wind became very strong, General Menou was

seized by a convulsive vomiting which seemed to cost him his life,

causing him to fall from his height, hitting his head on a cannon in the breech of his

ship. None of us could judge the danger of the large wound

he had sustained: he had lost consciousness; we deliberated whether we

should take it to the Orient, which was anchored with the fleet at

Aboukir, and opposite which we found ourselves at the moment.

(p.44)

Our sailors believed that a few hours would be enough for us to reach

the Nile: we chose this course, which would put an end to the general's

anxieties. Despite the torment of our situation and the rolling of the

vessel, I managed to draw a small view which gives an idea of the

anchorage of our fleet in front of Aboukir, of this promontory formerly

famous for the city of Canope and all its pleasures, today so famous

for all the horrors of war.

A few hours later we found ourselves,

without knowing it, at one of the mouths of the Nile, which we

recognized from the most disastrous scene I have seen in my life. The

waters of the Nile pushed back by the wind raised waves to an immense

height which were perpetually driven back and broken by the current of

the river with a terrible noise; one of our vessels which had just been

shipwrecked, and which the wave had just broken up, was the only clue

we had of the coast; several other opinions in the same situation as

us, that is to say in the same confusion, came closer to consult each

other, avoided each other so as not to break up, and could only hear

each other through even more terrible cries. There was no coastal

pilot; we no longer knew what to say; the general continued to get

worse: we thought of going to reconnoitre the bogaze or the bar of the

river; the boat was launched into the sea, and battalion commander

Bonnecarrere and I threw ourselves into it as best we could.

We

had barely left our shore when we found ourselves in the middle of the

abysses, without seeing anything other than the curved tops of the

waves which from all sides threatened to engulf us; a thousand toises

from the viso we could no longer reach him: seasickness began to

torment me; it was a question of waiting indefinitely, and thus passing

the night. I wrapped myself in my cloak to no longer see anything of

our deplorable situation, when we passed under the waters of a felucca,

where I saw an unfortunate man who, while getting into a (p.45) boat,

had remained suspended to a rope; tired of the efforts he made to

support himself in this perilous position, his arms stretched out and

let him go into those of death, which I saw open to receive him. I

experienced such a revolution at this spectacle that my fainting spells

stopped: I did not cry out, I howled; the sailors mixed their cries

with mine: they were finally heard by those in the ship; at first we

didn't know what we wanted; We sought on all sides beforehand to come

to the aid of the unfortunate man whose last strength was expiring; we

discover him at the end.... we still had time to save him.

The

moment that this event had caused us to lose, and the efforts that we

had made to keep ourselves under cover in case this man fell into the

sea, had made us gain enough height to regain our view; we climbed it

quite happily, and found ourselves at the same point from which we had

started without knowing more than to try. The wind calmed down a

little, but the sea remained rough: night came; it was less stormy.

The

general was too ill to make a resolution himself: we held another

council, and we resolved to put him in the boat as best we could,

thinking that the wrecked vessel and the breakers would serve as a

guide for us, and that in also avoiding we would enter the Nile: this

succeeds for us; after an hour of navigation we found ourselves at the

corner of the coast, and suddenly turning to the right, we sailed in

the most peaceful bed of the gentlest of all rivers, and half an hour

later in the middle of the freshest and greenest of all countries: it

was exactly leaving Ténare to enter via Lethe into the Champs-Elysées.

This was even more true for the general, who was already sitting up,

and only left us worried about the depth of his wound, which none of us

had dared to fathom.

(p.46) We soon found on our right a fort,

and on our left a battery, which, formerly built to defend the mouth of

the Nile, is now a league away; which could give the measure of the

progression of Falluvion of the river. Indeed, the construction of

these forts does not go back beyond the invention of gunpowder, and

they are therefore not more than three hundred years old. I quickly

made two drawings of these two points.

The first, to the west of

the river, presents a square castle, flanked by large towers at the

corners, with batteries in which were cannons twenty-five feet long;

the second is nothing more than a mosque, in front of which was a

ruined battery, of which a cannon, of twenty-eight inches caliber,

served no more than to provide happy childbirths to women when they

came to step over it. during their pregnancy.

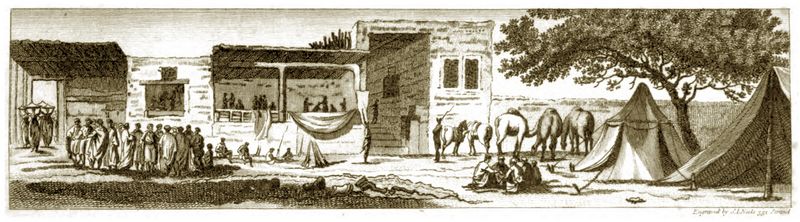

An hour later, we

discovered, in the middle of the forests of date palms, banana trees,

and sycamores, Rosette, located on the banks of the Nile, which without

damaging them, bathes the walls of its houses every year. I took a look

at it before approaching it.

Rascid, which the Franks called

Rosette, or Rosser, was built on the branch and near the Bolbitine

mouth, not far from the ruins of a town of that name, which must have

been located at a bend in the river, where is present the convent of

Abou-Mandour, half a league from Rosetta: what could support this

opinion are the heights which dominate this convent, and which must

have been formed by lands; These are still some columns and other

antiquities found while carrying out repairs to this convent around

twenty years ago.

Leo of Africa says that Rascid was built by a

governor of Egypt, under the reign of the caliphs; but it says neither

the name of the caliph nor the time of the foundation.

Rosette

offers no curious monuments. Its ancient (p.47) circumvallation

announces that it was larger than it is now; we recognize its first

enclosure by the sand mounds which cover it from west to south, and

which were only formed by the walls and towers which today serve as the

cores of these lands. As in Alexandria, the population of this city is

still decreasing. Little is built there, and what is built there is

nothing more than old bricks from buildings which are falling into ruin

due to lack of inhabitants and repairs. The houses, generally better

built than those of Alexandria, are however still so frail that, if

they were not spared by the climate which destroys nothing, there would

soon no longer be a house in Rosette; the floors, which always advance

one on the other, end up almost touching each other; which makes the

streets very dark and very sad. Dwellings along the Nile do not have

this disadvantage; they mostly belong to. foreign traders. This part of

the city would be easy to improve; it would only be necessary to build

on the bank of the river a quay alternately sloped and covered: the

houses, apart from the advantage of having a view of the navigation,

still have the pleasant aspect of the banks of the Delta, an island

which It is only a garden of a league in size.

This island first became our property, our promenade, and finally the

park

where we gave ourselves the pleasure of hunting, which was doubled by

that of curiosity, since each bird that we killed was a new

acquaintance.

I was able to notice that the inhabitants of the

left bank of the Nile, that is to say the inhabitants of the Delta,

were gentler and more sociable: I believe that the cause must be

attributed to greater abundance, and to absence of the Bedouin Arabs,

who, never crossing the river, leave them in a state of peace that the

others do not experience at any moment of their lives.

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |

| Southport main page Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2023 Rust Family Foundation.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|