|

Chapter 16 (p.233)

Pergamus of Troy, March 1st, 1873.

Since Monday morning, the 24th of last month, I have succeeded in increasing

the number of my workmen to 158, and as throughout this week we have

had splendid weather, I have been able to accomplish a good stroke of

work in the six days, in spite of the many hindrances and difficulties

which I had at first to struggle against. Since the 1st of February I

have succeeded in removing more than 11,000 cubic yards of débris from

the site of the temple.

To-day, at last, I have had the pleasure of

uncovering a large portion of that buttress, composed of large unhewn

white stones, which at one time covered the entire north-eastern corner

of the declivity, whereas, in consequence of its increase in size

during the course of many centuries by the ashes of the sacrificed

animals, the present declivity of the hill is 131 feet distant from it

to the north, and 262½ feet distant to the east. To my surprise I found

that this buttress reaches to within 26 feet of the surface, and thus,

as the primary soil is elsewhere always at from 46 to 52½ feet below

the surface, it must have covered an isolated hill from 20 to 26 feet

high, at the north-east end of the (p.234) Pergamus, where at one time

there doubtless stood a small temple.

Of this sanctuary, however, I

find nothing but red wood-ashes, mixed with the fragments of brilliant

black Trojan earthenware, and an enormous number of unhewn stones,

which seem to have been exposed to a fearful heat, but no trace of

sculpture: the building must therefore have been very small. I have

broken through the buttress of this temple-hill at a breadth of 13

feet, in order to examine the ground at its foundation. I dug it away

to a depth of 5 feet, and found that it consists of the virgin soil,

which is of a greenish colour. Upon the site of the small and very

ancient temple, which is indicated by the buttress, I find in two

places pure granular sand, which appears to extend very far down, for

after excavating it to a depth of 6½ feet I did not reach the end of

the stratum. Whether this hill consists entirely, or but partially, of

earth and sand, I cannot say, and must leave it undecided, for I should

have to remove thousands more of cubic yards of rubbish.

Among the

débris of the temple we found a few, but exceedingly interesting

objects, for instance, the largest marble idol that has hitherto been

found, which is 5¼ inches long and 3 inches broad (fig.163).

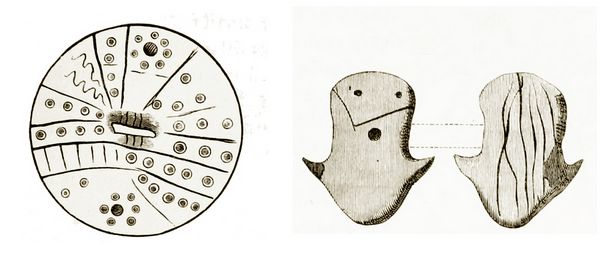

Fig.163: One of the largest marble Idols, found in the Trojan Stratum (8m depth).

Further, the lid of

a pot, which is divided into twelve fields by roughly engraved lines.

Ten of the fields are ornamented with little stars, one with two signs

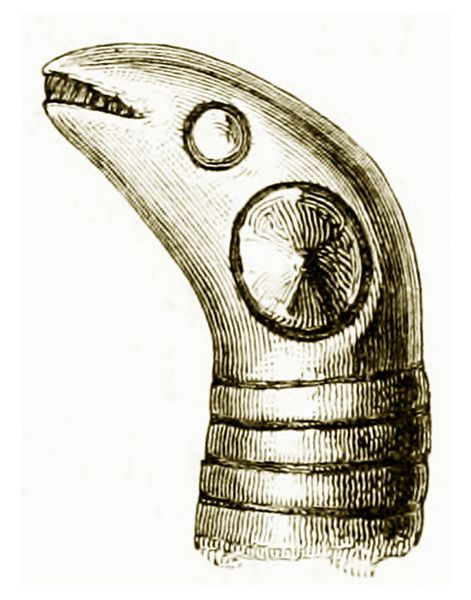

of lightning, and another with six lines (fig.164). There was also a small idol

of terra-cotta with the owl’s head of the Ilian tutelary goddess, with

two arms and long hair hanging down at the back of the head; but it is

so roughly made that, for instance, the eyes of the goddess are above

the eyebrows (fig.165). I also found among the débris of the temple a vase with

the (p.235) owl’s face, two female breasts and a large navel; of the face

only one eye and an ear is preserved. I must draw especial attention to

the fact that both upon the vases with owls’ heads two female breasts

and a navel, and upon all of the others without the owl’s face and

adorned only with two female breasts and a navel, the latter is always

ten times larger than the breasts. I therefore presume that the navel

had some important significance, all the more so as it is frequently

decorated with a cross, and in one case even with a cross and the marks

of a nail at each of the four ends of the cross.[220] We also

discovered among the ruins of the small and very ancient building some

pretty wedges (battle-axes), and a number of very rude hammers made of

diorite; besides a quantity of those small red and black terra-cotta

whorls, with the usual engravings of four or five ?, or of three, four,

or five triple rising suns in the circle round the central sun, or with

other extremely strange decorations.

Fig.164 (left): Terra-cotta Pot-lid, engraved with symbolical marks (6m depth).

Fig.165 (right):A curious Terra-cotta Idol of the Ilian Athena (7m depth.).

At

a depth of 7 to 8 meters (23 to 26 feet), we also came upon a number of

vases having engraved decorations, and with three feet or without feet,

but generally with rings at the sides and holes in the mouth for

suspension by strings; also goblets in the form of a circular tube,

with a long spout at the side for drinking out of, which

is always (p.236)

connected with the other side of the tube by a handle; further, smaller

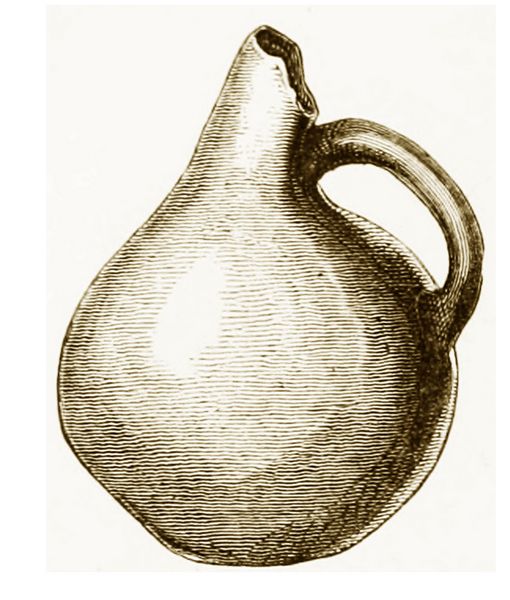

or larger jars with a mouth completely bent backwards (fig.166); small

terra-cotta funnels; very curious little sling-bullets made of diorite,

from only ¾ of an inch to above 1 inch long.

Fig.166: Pretty Terra-cotta jug, with the neck bent back (7m depth).

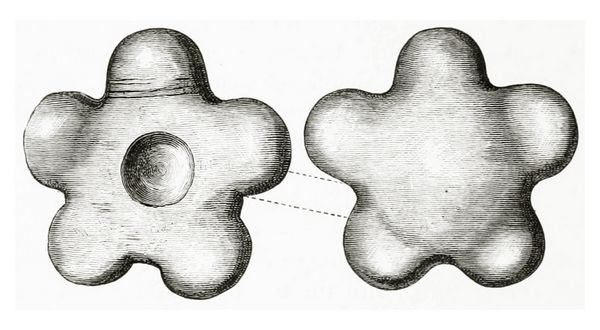

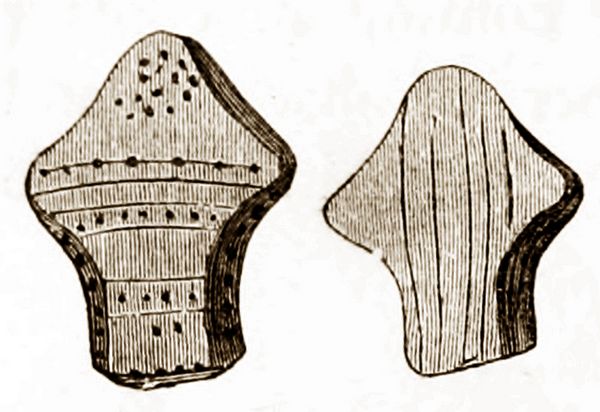

The most remarkable of all

the objects found this year is, however, an idol of very hard black

stone above 2½ inches long and broad (fig.167), discovered at a depth of 9 meters

(29½ feet). The head, hands, and feet have theform of hemispheres, and

the head is only recognised by several horizontal lines engraved below

it, which seem to indicate necklaces. In the centre of the belly is a

navel, which is as large as the head, but, instead of protruding as in

the case of the vases, it is indicated by a circular depression.

The

back of the middle of the body is arched, and has the appearance of a

shield, so that in looking at the idol one is involuntarily led to

believe that it represents Mars, the god of war.

No.167: Remarkable Trojan Idol of Black Stone (7m depth).

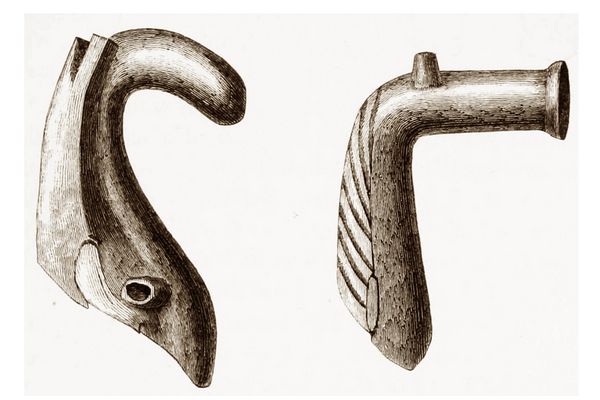

At

a depth of from 4 to 7 meters (13 to 23 feet) we also met with

fragments of terra-cotta serpents, whose heads are sometimes

represented with horns (figs.168,169).

Figs.168,169: Heads of Horned Serpents (4m depth).

The latter must (p.237) certainly be a very

ancient and significant symbol of the greatest importance, for even now

there is a superstition that the horns of serpents, by merely coming in

contact with the human body, cure a number of diseases, and especially

epilepsy; also that by dipping them in milk the latter is instantly

turned into cheese, and other notions of the same sort. On account of

the many wholesome and useful effects attributed to the horns of

serpents, they are regarded as immensely valuable, and on my return

here at the end of January one of my last year’s workmen was accused by

a jealous comrade of having found two serpents’ horns in an urn at a

depth of 52½ feet, and of having made off with them.

All my assurances

that there are no such things as serpents horns could not convince the

men, and they still believe that their comrade has robbed me of a great

treasure.

Fig.170: A Serpent’s Head, with horns on both sides, and very large eyes (6m depth).

The serpents’ heads not ornamented with horns generally

represent the poisonous asp; above the mouth they have a number of

dots, and the head and back are divided (p.238) by cross lines into

sections which are filled with dots.[221] These flat serpents’ heads

have on the opposite side lines running longitudinally like female

hair. We also found terra-cotta cones an inch and a half high, with

three holes not pierced right through. At a depth of from 3¼ to 6½ feet

we have discovered several more terra-cotta vases without the owl’s

face, but with two female breasts and a large navel, and with two small

upright handles in the form of arms.

In all the strata below 13 feet we

meet with quantities of implements of diorite, and quoits of granite,

sometimes also of hard limestone. Hammers and wedges (battle-axes) of

diorite and of green stone were also found, in most cases very prettily

wrought. The hammers do not all possess a perforated hole; upon many

there is only a cavity on both sides, about 1/5 to 2/5 of an inch deep.

Fig.171: Head of an Asp in Terra-cotta (both sides) (4 M.).

Of

metals, copper only was met with. To-day we found a copper sickle 5½

inches long; of copper weapons we have to-day for the first time found

two lances at a depth of 23 feet, and an arrow-head at 4 meters (13

feet) deep. We find numbers of long, thin copper nails with a round

head, or with the point only bent round. I now also find them

repeatedly at a depth of from 5 to 6 meters (16½ to 20 feet), whereas

since the commencement of my excavations in the year 1871, I only found

two nails as far down as this.[222] (p.239).

I am now also

vigorously carrying forward the cutting which I made on the

south-eastern corner of the Pergamus, for uncovering the eastern

portion of the Great Tower as far as my last year’s cutting, to a

length of 315 feet and a breadth of from 65½ to 78¾ feet. The work

advances rapidly, as this excavation is near the southern declivity of

the hill, and the rubbish has therefore not far to be carted off. I

have made eight side passages for removing it. Experience has taught me

that it is far more profitable not to have any special men for loading

the wheel-barrows, but to let every workman fill his own barrow.

Experience has also shown me that much precious time is lost in

breaking down the earthen walls with the long iron levers driven in by

a ram, and that it is much more profitable and less dangerous to the

workmen always to keep the earthen walls at an angle of 55 degrees, to

dig as occasion requires, and to cut away the rubbish from below with

broad pickaxes.

In this new excavation I find four earthen pipes, from

18¾ to 22¼ inches long, and from 6½ to 11¾ inches thick, laid together

for conducting water, which was brought from a distance of 1½ German

mile (about 7 English miles) from the upper Thymbrius. This river is

now called the Kemar, from the Greek word ?aµ??a (vault), because an

aqueduct of the Roman period crosses its lower course by a large arch.

This aqueduct formerly supplied Ilium with drinking water from the

upper portion of the river. But the Pergamus required special

aqueducts, for it lies higher than the city.

In this excavation

I find an immense number of large earthen wine-jars (p????) from 1 to 2

meters (3¼ to 6½ feet) high, and 29½ inches across, as well as a number

of fragments of Corinthian pillars and other splendidly sculptured

blocks of marble. All of these marble blocks must certainly have

belonged to those grand buildings whose southern wall I have already

laid bare to a length of (p.240) 285½ feet. It is composed of small stones

joined with a great quantity of cement as hard as stone, and rests upon

large well hewn blocks of limestone. The direction of this wall, and

hence of the whole building, is E.S.E. by E.

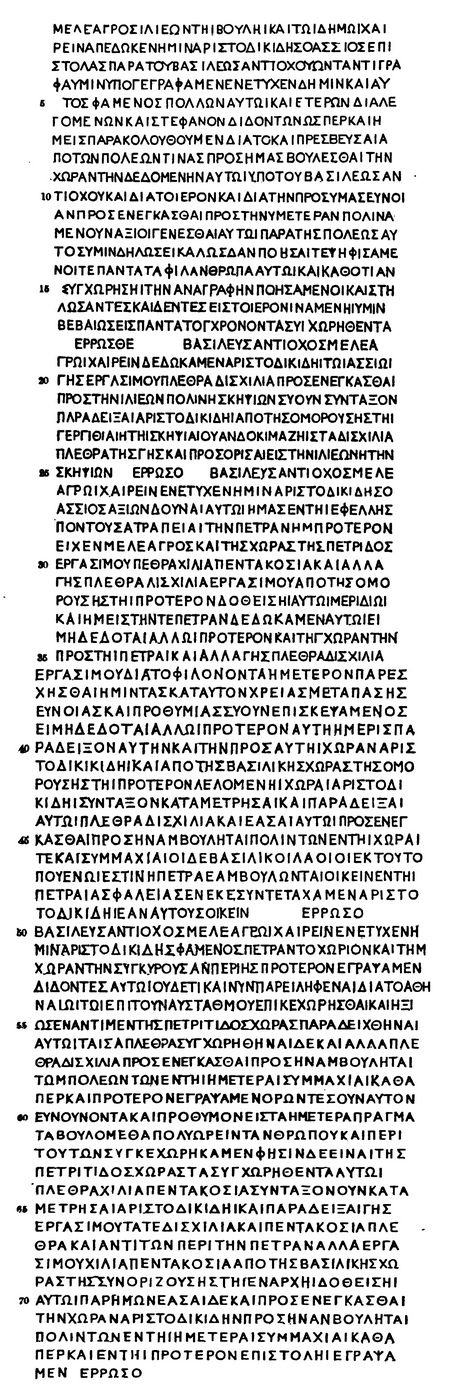

Three inscriptions,

which I found among its ruins, and in one of which it is said that they

were set up in the “?e???,” that is, in the temple, leave no doubt that

this was the temple of the Ilian Athena, the “p???????? ?e?,” for it is

only this sanctuary that could have been called simply “t? ?e???,” on

account of its size and importance, which surpassed that of all the

other temples of Ilium. Moreover the position of the building, which is

turned towards the rising sun, corresponds exactly with the position of

the Parthenon and all the other temples of Athena. From the very

commencement of my excavations I have searched for this important

sanctuary, and have pulled down more than 130,000 cubic yards of débris

from the most beautiful parts of the Pergamus in order to find it; and

I now discover it exactly where I should have least expected to come

upon it. I have sought for this new temple, which was probably built by

Lysimachus, because I believed, and still believe, that in its depths I

shall find the ruins of the primeval temple of Athena, and I am more

likely here than anywhere to find something to throw light upon Troy.

Of the inscriptions found here, as mentioned above, one is written upon

a marble slab in the form of a tombstone, 5¼ feet long, 17½ inches

broad, and 5¾ inches thick, and runs as follows:—

"Meleager greets the Council and the people

of Ilium. Aristodicides, of Assos, has handed

to us letters from king Antiochus, the copies of

which

we have written out for you. He (Aristodicides) came to meet us

himself, and told us that though many other cities apply to him and

offer him a crown, just.as we also understand because some have sent

embassies to us from the cities, nevertheless, prompted by his

veneration for the temple (of the I/ian Athené), as well as by his

feeling of friendship for your town, he is willing to offer to you the

land which king Antiochus has presented to him. Now, he will

communicate to you what he claims to be done for him by the city. Thus

you would do well to vote for him every kind of hearty

friendship, and, whatever concession he may make, do you put it on

record, engrave it on a stone slab, ard set it up in the temple, in

order that the concession may be safely preserved to you for ever.

Farewell.

“King Antiochus greets Meleager. We have granted to

Aristodicides, the Assian, two thousand plethra of arable land, for him

to confer on the city of Jliwm, or on the city of Scepsis. Order

therefore that the two thousand plethra of land be assigned to

Aristodicides, wherever you may think proper, of the land which borders

on the territory of Gergis, or on that of Scepsis, and that they be

added to the city of the Ilians, or to that of the Scepsians. Farewell.

“

King Antiochus greets Meleager. Aristodicides, the Assian, came to

meet us, begging that we would give him, in the satrapy of the

Hellespont, Petra, which Meleager formerly had, and in the territory of

Petra one thousand five hundred plethra of arable land, and two

thousand plethra more of arable land bordering

on the portion which

had been given to him first as his share; and we have given Petra to

him, provided it has not yet been given to some one else; and we have

also presented to him the land near Petra, and two thousand plethra

more of arable land, because he is our friend and has supplied to us

all that we required, as far as he could, with kindness and

willingness. Do

you then, having examined if that portion has not

already been given to some one else, assign it to Aristodicides, as

well as the land near it, and order that of the royal domain which

borders on the land first granted to Aristodicides two thousand plethra

be m>asured off and assigned to him, and leave it to him to confer

the land on what town soever in the country or confederacy he pleases.

Regarding the royal subjects in the estate in which Petra is situated,

if for

safety’s sake they wish to live in Petra, we have

recommended Aristodicides to let them remain

there. Farewell.

“King

Antiochus greets Meleager. Aristodicides came to meet us, saying that

Petra, the district and the land with it, which we gave to him in our

former letter, is no longer

disposable, it having been granted to Athenaeus,

the commandant of the naval station; and he

begged that, instead of the land of Petra, the

same number of plethra might be assigned to him

(elsewhere), and that he might be permitted to

confer another lot of two thousand plethra of land

on whichsoever of the cities in our confederacy

he might choose, according as we wrote before.

Now, seeing him friendly disposed and zealous

for our interests, we wish to show great regard

fot the man’s interest, and have complied with

his request about these matters. He says that

his grant of land at Petra amounts to fifteen

hundred plethra. Give order therefore that the

two thousand five hundred plethra of arable

land be measured out and assigned to Aristodicides

; and further, instead of the land

around Petra, another lot of fifteen hundred

plethra of arable land, to be taken from the

royal domains bordering on the estate which we

first granted to him. Let now Aristodicides

confer the land on whichsoever of the cities in

our confederacy he may wish, as we have written

in our former letter. Farewell.”

(pp.241-244)

This

inscription, the great historical value of which cannot be denied,

seems certainly to belong to the third century B.C., judging from the

subject as well as from the form of the letters, for the king Antiochus

repeatedly mentioned must either be Antiochus I., surnamed Soter (281

to 260 B.C.), or Antiochus III., the Great (222 to 186). Polybius, who

was born in 210 or 200 B.C., and died in 122 B.C., in his History

(XXVIII. 1, and XXXI. 21) speaks indeed of a Meleager who lived in his

time, and was an ambassador of Antiochus Epiphanes, who reigned from

174 to 164, and it is quite possible that this Meleager afterwards

became satrap of the satrapy of the Hellespont, and that, in this

office, he wrote to the Ilians the first letter of this inscription.

But in the first letter of Antiochus to his satrap Meleager, he gives

him the option (p.245) of assigning to Aristodicides the 2000 plethra of

land, either from the district bordering upon the territory of Gergis

or upon that of Scepsis. The town of Gergis, however, according to

Strabo, was destroyed by king Attalus I. of Pergamus, who reigned from

241 to 197 B.C., and who transplanted the inhabitants to the

neighbourhood of the sources of the Caļcus in Mysia. These sources,

however, as Strabo himself says, are situated very far from Mount Ida,

and hence also from Ilium. Two thousand plethra of land at such a

distance could not have been of any use to the Ilians; consequently, it

is impossible to believe that the inscription can be speaking of the

new town of Gergitha, which was rising to importance at the sources of

the Caļcus.

I now perfectly agree with Mr. Frank Calvert,[226] and with

Consul von Hahn,[227] that the site of Gergis is indicated by the ruins

of the small town and acropolis at the extreme end of the heights

behind Bunarbashi, which was only a short time ago regarded by most

archęologists as the site of the Homeric Troy. This site of Gergis, in

a direct line between Ilium and Scepsis, the ruins of which are to be

seen further away on the heights of Mount Ida, agrees perfectly with

the inscription. Livy (XXXV. 43) gives an account of the visit of

Antiochus III., the Great. I also find in the ‘Corpus Inscriptionum

Gręcarum,’ No. 3596, that the latter had a general called Meleager, who

may subsequently have become satrap of the Hellespont.

On the other

hand, Chishull, in his Antiquitates Asiaticę, says that Antiochus I.,

Soter, on an expedition with his fleet against the King of Bithynia,

stopped at the town of Sigeum, which lay near Ilium, and that the king

went up to Ilium with the queen, who was his wife and sister, and with

the great dignitaries and his suite. There is, indeed, nothing said of

the brilliant reception which was there prepared{246} for him, but

there is an account of the reception which was arranged for him in

Sigeum. The Sigeans lavished servile flattery upon him, and not only

did they send ambassadors to congratulate him, but the Senate also

passed a decree, in which they praised the king’s actions to the skies,

and proclaimed that public prayers should be offered up to the Ilian

Athena, to Apollo (who was regarded as his ancestor), to the goddess of

Victory and to other deities, for his and his consort’s welfare; that

the priestesses and priests, the senators and all the magistrates of

the town should carry wreaths, and that all the citizens and all the

strangers settled or temporarily residing in Sigeum should publicly

extol the virtues and the bravery of the great king; further, that a

gold equestrian statue of the king, standing on a pedestal of white

marble, should be erected in the temple of Athena in Sigeum, and that

it should bear the inscription: “The Sigeans have erected this statue

to King Antiochus, the son of Seleucus, for the devotion he has shown

to the temple, and because he is the benefactor and the saviour of the

people; this mark of honour is to be proclaimed in the popular

assemblies and at the public games.” However, in this wilderness it is

impossible for me to find out from which ancient classic writer this

episode has been taken.

It is very probable that a similar

reception awaited Antiochus I. in Ilium, so that he kept the city in

good remembrance. That he cherished kindly feelings towards the Ilians

is proved also by the inscription No. 3595 in the ‘Corpus Inscriptionum

Gręcarum.’ But whether it is he or Antiochus the Great that is referred

to in the inscription I do not venture to decide.

Aristodicides,

of Assos, who is frequently mentioned in the inscription, is utterly

unknown, and this name occurs here for the first time; the name of the

place Petra also, which is mentioned several times in the inscription,

is quite unknown; it must have been situated in this neighbourhood, but

all my endeavours to discover it in the modern (p.247)Turkish names of

the localities, or by other means, have been made in vain.

The other inscription runs as follows:—

O??????????

?S??? ??????????SG?????

???G?????????SS???????????????????G?F?????????S??

???????S???????O?????????O????????O??O????????

F?????G?S???????F?????????S????????????S??????S???5

???????G???????S???????????????O???F???????????????

?????O?????????O?????S????O????????O??O????????F????

?G?S??????????????S????S?F??????S???S??????O?S??????S???

??????????????????????????????????????????????S???????

????????O?????S????O?????F???O?????????????????10

??O??F?????????S??????O?S??????S???

???????O???????F??????????O?????????O???

??F????O??O??????????????G?S???????F????

??S??????S???

........................

...................????? t?? ??d....

......?sµe?.........???aµe?a??? ??a???..

?pe????aµe? e?? st???? ?at? t?? ??µ?? ????f???? ?at??s?? (;)

???µat??[228] ??[229] ???µ??µ???? ?p? t?? p??t??e??[230] t?? pe?? ???-

f???? ???s?d?µ??, ?(f)????ta t??? ?at(?) t?? ??µ?? stat??a? d??5

?a? ????????? ???s(???;)?? ?a? ??teµ?d???? Fa??a ?a? ???µ?d??

?p????????, ???µ??µ????? ?p? t?? p??t??e?? t?? pe?? ???f?(???)

???s?d?µ?? ?p? ?µ??a? t?e?? ?f????ta? ??ast?? a?t?? stat??a? d??.

????d?t?? ????d?t?? ?a? ??a??e?d?? ?a? ????d?t?? t??? ??a??e?-

d?? ???µ??µ????? ?p? t?? pe?? Fa????a?ta ??d?µ?? p??t?-10

?e??, ?fe????ta ??ast?? a?t?? stat??a? d??.

??teµ?d???? ????f??t?? ???µ??µ???? ?p? t?? ??-

µ?f?????? t?? pe?? ?ppa???? ???s?d?µ??, ?f????-

ta stat??a? d??.

In

the inscription quoted in the Corpus Inscriptionum Gręcarum under No.

3604, which is admitted to belong to the time of Augustus Octavianus,

Hipparchus is mentioned as a member of the Ilian Council, and as on

line 13 the same name occurs with the same attribute, I do not hesitate

to maintain that the above inscription belongs to the same period. (p.248)

.

Footnotes:

[220] See Cut, No. 13, p. 35.

[221]

The serpents’ heads, found so frequently among the ruins of Troy,

cannot but recal to mind the superstitious regard of Homer’s Trojans

for the reptile as a symbol, and their terror when a half-killed

serpent was dropped by the bird of Jove amidst their ranks (Iliad, XII. 208, 209):—

???e? d’ ??????sa?, ?p?? ?d?? a????? ?f??

?e?µe??? ?? µ?ss??s?, ???? t??a? a????????.

“The Trojans, shuddering, in their midst beheld

The spotted serpent, dire portent of Jove.”

[222] That is, in the strata of the third dwellers on the hill.

[223] sic

[224] sic.

[225] sic.

[226] Archęological Journal, vol. xxi. 1864.

[227] Die Ausgrabungen auf der homerischen Pergamos, s. 24.

[Continue to Chapter 17]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|