|

Chapter 9

On the Hill of Hissarlik, May 23rd, 1872.

SINCE

my report of the 11th instant there have again been, including to-day,

three great and two lesser Greek church festivals, so that out of these

twelve days I have in reality only had seven days of work. Poor as the

people are, and gladly as they would like to work, it is impossible to

persuade them to do so on feast days, even if it be the day of some

most unimportant saint. ??? d???e? ? ????? ("the saint will strike us”)

is ever their reply, when I try to persuade the poor creatures to set

their superstition aside for higher wages.

In order to hasten

the works, I have now had terraces made at from 16 to 19 feet above the

great platform on its east and west ends; and I have also had two walls

made of large blocks of stone—the intermediate spaces being filled with

earth—for the purpose of removing the débris. The smaller wall did not

seem to me to be strong enough, and I kept the workmen from it; in

fact, it did not{132} bear the pressure, and it fell down when it was

scarcely finished. Great trouble was taken with the larger and higher

wall: it was built entirely of large stones, for the most part hewn,

and all of us, even Georgios Photidas, thought it might last for

centuries. But nevertheless on the following morning I thought it best

to have a buttress of large stones erected, so as to render it

impossible for the wall to fall; and six men were busy with this work

when the wall suddenly fell in with a thundering crash. My fright was

terrible and indescribable, for I quite believed that the six men must

have been crushed by the mass of stones; to my extreme joy, however, I

heard that they had all escaped directly, as if by a miracle.

In

spite of every precaution, excavations in which men have to work under

earthen walls of above 50 feet in perpendicular depth are always very

dangerous. The call of “guarda, guarda” is not always of avail, for

these words are continually heard in different places. Many stones roll

down the steep walls without the workmen noticing them, and when I see

the fearful danger to which we are all day exposed, I cannot but

fervently thank God, on returning home in the evening, for the great

blessing that another day has passed without an accident. I still think

with horror of what would have become of the discovery of Ilium and of

myself, had the six men been crushed by the wall which gave way; no

money and no promises could have saved me; the poor widows would have

torn me to pieces in their despair—for the Trojan women have this in

common with all Greeks of their sex, that the husband, be he old or

young, rich or poor, is everything to them; heaven and earth have but a

secondary interest.

Upon the newly made western terrace,

directly beside my last year’s excavation, we have laid bare a portion

of a large building—the walls of which are 6¼ feet thick, and consist

for the most part of hewn blocks of limestone joined with clay. (No. 24

on Plan II.) None of the stones{133} seem to be more than 1 foot 9

inches long, and they are so skilfully put together, that the wall

forms a smooth surface. This house is built upon a layer of yellow and

brown ashes and ruins, at a depth of 6 meters (20 feet), and the

portion of the walls preserved reaches up to within 10 feet below the

surface of the hill.

In the house, as far as we have as yet excavated,

we found only one vase, with two breasts in front and one breast at the

side; also a number of those frequently mentioned round terra-cottas in

the form of the volcano and top, all of which have five or six

quadruple rising suns in a circle round the central sun.[134] These

objects, as well as the depth of 6 meters (20 feet), and the

architecture of the walls described above, leave no doubt that the

house was built centuries before the foundation of the Greek colony,

the ruins of which extend only to a depth of 6½ feet.

It is with a

feeling of great interest that, from this great platform, that is, at a

perpendicular height of from 33 to 42 feet, I see this very ancient

building (which may have been erected 1000 years before Christ)

standing as it were in mid air. To my regret, however, it must in any

case be pulled down, to allow us to dig still deeper. As I said before,

directly below this house there is a layer of ruins consisting of

yellow and brown ashes, and next, as far as the terrace, there are four

layers more of ashes and other débris, each of which represents the

remains of one house at least.

Immediately above the terrace, that is

13 feet below the foundation of that very ancient house, I find a wall

about 6 feet thick, built of large blocks of limestone, the description

of which I must reserve for my next report, for a large portion of the

building I have mentioned, and immense masses of the upper strata of

débris, as well as the high earthen wall of the terrace (26 feet thick

and 20 feet high) must be pulled down, before I can lay bare any

portion of this wall and investigate how far down it extends.{134} If

it reaches to or even approaches the primary soil, then I shall

reverently preserve it. (See No. 25 on Plan II.)

It is a very

remarkable fact, that this is the first wall built of large stones that

I have hitherto found at the depth of from 10 to 16 meters (33 to 52½

feet).[135] I cannot explain this, considering the colossal masses of

loose stones which lie irregularly beside one another (especially at a

depth of from 36 to 52½ feet), in any other way than by supposing that

the houses of the Trojans were built of blocks of limestone joined with

clay, and consequently easily destroyed. If my excavations are not

interrupted by any accident, I hope, in this at all events, to make

some interesting discoveries very soon, with respect to this question.

Unfortunately

during the last twelve days I have not been able to pull down much of

the lower firm earth-wall, for, in order to avoid fatal accidents, I

have had to occupy myself especially in making and enlarging the side

terraces. I have now, however, procured enormous iron levers of nearly

10 feet in length and 6 inches in circumference, and I thus hope

henceforth to be able at once to break down, by means of windlasses,

the hardest of the earth-walls, which are 10 feet thick, 66 broad, and

from 16 to 26 feet high.

In the small portion of the earth-wall pulled

down during these last days, I repeatedly found the most irrefutable

proofs of a higher civilization; but I will only mention one of these,

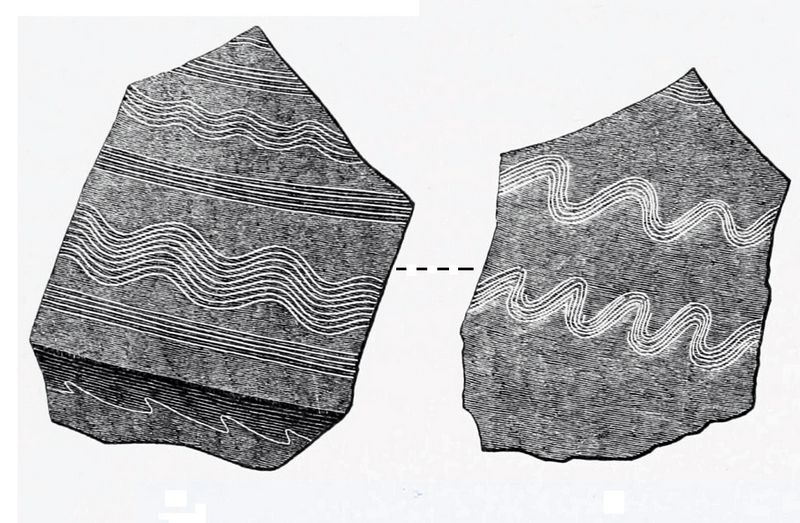

a fragment of a brilliant dark grey vessel (fig.79)which I have at present

lying before me, found at a depth of 15 meters (49 feet). It may

probably have been nearly 2 feet in diameter, and it has decorations

both outside and inside, which consist of engraved horizontal and

undulating lines. The former are arranged in three sets in stripes of

five lines, and the lowest space is adorned with eight and the

following with five undulating lines, which are probably meant to

represent the waves of the sea; of the{135} next set no part has been

preserved; the thickness of the clay is just 3/5 of an inch.

Fig.79:. Fragment of a brilliant dark-grey Vessel, from the Lowest Stratum (15m depth). left: Inside; right: Outside.

In

my report of the 25th of last month,[136] I mentioned the discovery of

one of those terra-cottas upon which were engraved three animals with

antlers in the circle round the central sun. Since then four others of

these remarkable objects with similar engravings have been discovered.

Upon one of them, found at a depth of 6 meters (20 feet), there are

only two animals with antlers in the circle round the sun, and at the

end of each antler, and connected with it, is an exceedingly curious

sign resembling a large candlestick or censer, which is certainly an

especially important symbol, for it is repeatedly found here standing

alone.[137]

Upon a second, there is below a rough representation of a

man who seems to be praying, for he has both arms raised towards

heaven; this position reminds us forcibly of the two uplifted arms of

the owl-faced vases; to the left is an animal with but two feet and two

trees on its back.[138] Indian scholars will perhaps find that this is

intended to represent the falcon, in which shape the sun-god stole the

sacred sôma-tree from{136} heaven. Then follow two animals with two

horns, probably antelopes, which are so frequently met with upon

ancient Greek vases, and which in the Rigvêda are always made to draw

the chariot of the winds. Upon a third terra-cotta there are three of

these antelopes with one or two rows of stars above the back, which

perhaps are intended to represent heaven; then five fire-machines, such

as our Aryan ancestors used; lastly, a sign in zigzag, which, as

already said, cannot represent anything but the flaming altar.[139]

Upon the fourth whorl are four hares, the symbols of the moon, forming

a cross round the sun. They probably represent the four seasons of the

year.[140]

At a depth of 14 meters (46 feet) we found to-day two

of those round articles of a splendidly brilliant black terra-cotta,

which are only 3/5 of an inch in height, but 2-1/3 inches in diameter,

and have five triple rising suns and five stars in the circle round the

central sun. All of these decorations, which are engraved, as in every

other case, are filled in with a very fine white substance. When

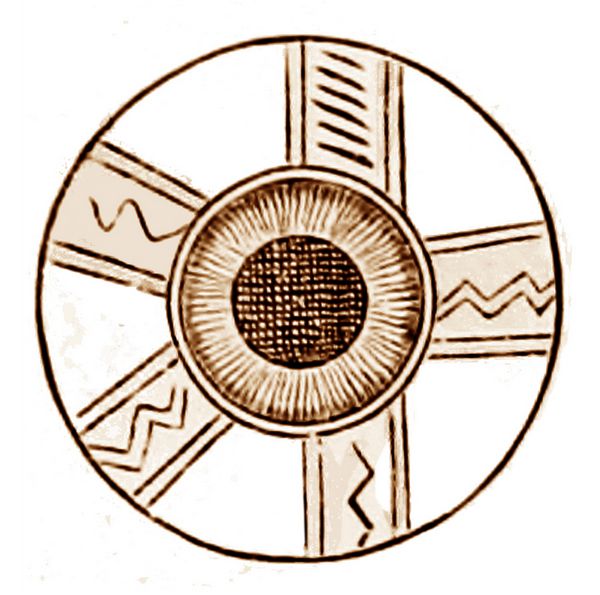

looking at these

curious articles, one of which is exactly the shape of

a carriage-wheel (fig.80),[141] the thought involuntarily strikes me that they

are symbols of the sun’s chariot, which, as is well known, is

symbolized in the Rigvêda by a wheel, and that all and each of these

articles met with in the upper strata (although their form deviates

from that of a wheel on account of their greater thickness) cannot be

anything but degenerated representations of the sun’s wheel. Fig.80: Whorl with pattern of a moving Wheel (16m depth).

I

conjecture this all the more, because not only is the sun the

central{137} point of all the round terra-cottas, but it is almost

always surrounded by one, two, three, four or five circles, which may

represent the nave of the wheel. At a depth of 16 meters (52½ feet) we

found a round terra-cotta, which is barely an inch in diameter, and a

fifth of an inch thick; there are five concentric circles round the

central point, and between the fourth and fifth circle oblique little

lines, which are perhaps meant to denote the rotation of the wheel.

I

must here again refer to the round terra-cotta mentioned in my report

of the 18th of November, 1871,[142] and to my regret I must now express

my firm conviction that there are no letters upon it, but only

symbolical signs; that for instance the upper sign (which is almost

exactly the same as that upon the terra-cotta lately cited)[143] must

positively represent a man in an attitude of prayer, and that the three

signs to the left can in no case be anything but the fire-machine of

our Aryan ancestors, the ? little or not at all changed. The sign which

then follows, and which is connected with the fourth and sixth signs, I

also find, at least very similar ones, on the other, cited in the same

report, but I will not venture to express an opinion as to what it may

mean.[144]

Fig.81: Whorl with Symbols of Lightning (7m depth)

All

the primitive symbols of the Aryan race, which I find upon the Trojan

terra-cottas, must be symbols of good men, for surely only such would

have been engraved upon the thousands of terra-cottas met with here.

Yet these symbols remind one forcibly of the “s?µata ?????” and

“??µ?f???a,” which King Prœtus of Tiryns gave to Bellerophon to take to

his father-in-law in Lycia.[146] Had he scratched a symbol of good

fortune, for instance a ?, upon the folded tablet, it would assuredly

have sufficed to secure him a good reception, and protection. But he

gave him the symbol of death, that he might be killed.

The

five [six] characters found on a small terra-cotta disc at a depth of

24 feet, and which in my report of November 18th, 1871,[147] I

considered to be Phœnician, have unfortunately been proved not to be

Phœnician, for M. Ernest Renan of Paris, to whom I sent the small disc,

finds nothing Phœnician in the symbols, and maintains that I could not

find anything of the kind in Troy, as it was not the custom of the

Phœnicians to write upon terra-cotta, and moreover that, with the

exception of the recently discovered Moabite inscription of King Mesha,

no Phœnician inscription has{139} ever been found belonging to a date

anterior to 500 years B.C.

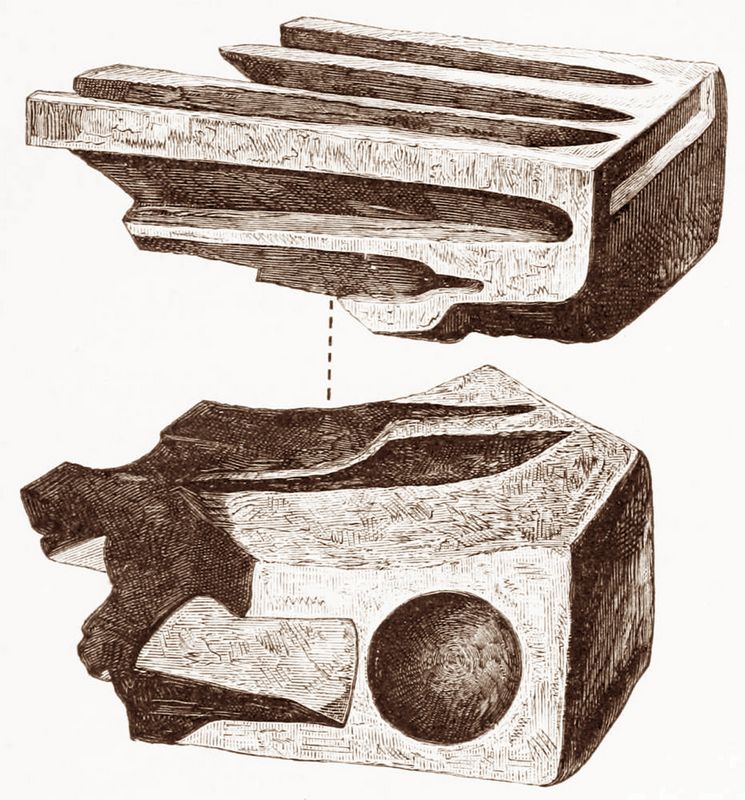

Fig.82: Two fragments of a great Mould of Mica-schist for casting Copper Weapons and Ornaments (14m depth).

Of cellars, such as

we have in civilized countries, I have as yet found not the slightest

trace, either in the strata of the Hellenic or in those of the

pre-Hellenic period; earthen vessels seem everywhere to have been used

in their stead. On my southern platform, in the strata of Hellenic

times, I have already had ten such vessels dug out in an uninjured

condition; they are from 5¾ to 6½ feet high, and from 2 to 4½ feet in

diameter, but without decorations.[149] I sent seven of these jars

(p????) to the Museum in Constantinople.

In the strata of the

pre-Hellenic period I find an immense number of these p????, but I have

as yet only succeeded in getting two of them out uninjured, from a

depth of 26 feet; these are about 3½ feet high and 26¾ inches in

diameter; they have only unimportant decorations.

In my last

communication, I was able to speak of a lesser number of the blocks of

stone obstructing the works upon the great platform; to-day, however, I

have again unfortunately to report a considerable increase of them.

At

a distance of scarcely 328 yards from my house, on the south side, and

at the part of the plateau of Ilium in a direct perpendicular line

below the ruined city wall, which seems to have been built by

Lysimachus, I have now discovered the stone quarry, whence all those

colossal masses of shelly limestone (Muschelkalk) were obtained, which

the Trojans and their successors, down to a time after the Christian

era, employed in building their houses and walls, and which have given

my workmen and me such inexpressible anxiety, trouble, and labour.

The

entrance to the quarry, which is called by the native Greeks and Turks

“lagum” ("mine” or “tunnel,” from the Arabic word ???, which has passed

over into Turkish), is filled with rubbish, but, as I am assured by all

the people about{141} here, it was still open only 20 years ago, and,

as my excavations have proved, it was very large. The town, as seems to

be indicated by a continuous elevation extending below the quarry, had

a double surrounding wall at this point, and this was in fact

necessary, for otherwise the enemy would have been able, with no

further difficulty, to force his way into the quarry below the

town-wall, as the entrance to the quarry was outside of the wall.

Unfortunately,

without possessing the slightest knowledge of medicine, I have become

celebrated here as a physician, owing to the great quantity of quinine

and tincture of arnica which I brought with me and distributed

liberally, and by means of which, in October and November of last year,

I cured all fever patients and wounds. In consequence of this, my

valuable time is now claimed in a troublesome manner by sick people,

who frequently come from a distance of many miles, in order to be

healed of their complaints by my medicine and advice.

In all the

villages of this district, the priest is the parish doctor, and as he

himself possesses no medicines, and is ignorant of their properties,

and has besides an innate dislike to cold water and all species of

washing, he never uses any other means than bleeding, which, of course,

often kills the poor creatures. Wrinkles on either side of the lips of

children from 10 to 12 years of age show that the priest has repeatedly

bled them. Now I hate the custom of bleeding, and am enthusiastically

in favour of the cold-water cure; hence I never bleed anyone, and I

prescribe sea-bathing for almost all diseases; this can be had here by

everyone, except myself, who have no time for it.

My ordering these

baths has given rise to such confidence, nay enthusiasm, that even

women, who fancied that it would be their death to touch their bodies

with cold water, now go joyfully into the water and take their dip.

Among others, a fortnight ago, a girl of seventeen from Neo-Chori was

brought to me; her body was covered with{142} ulcers, especially her

face, and one terrible ulcer on the left eye had made it quite useless.

She could scarcely speak, walk or stand, and, as her mother said, she

had no appetite; her chest had fallen in, and she coughed. I saw

immediately that excessive bleeding and the consequent want of blood

had given rise to all her ailments, and therefore I did not ask whether

she had been bled, but how many times.

The answer was, the girl had

taken cold, and the parish priest had bled her seven times in one

month. I gave her a dose of castor oil, and ordered her a sea bath

every day, and that, when she had recovered sufficient strength, her

father should put her through some simple passive gymnastic

exercises—which I carefully described—in order to expand her chest. I

was quite touched when early this morning the same girl appeared on the

platform, threw herself on the ground, kissed my dirty shoes, and told

me, with tears of joy that even the first sea bath had given her an

appetite, that all the sores had begun to heal directly, and had now

disappeared, but that the left eye was still blind, otherwise she was

perfectly well, for even the cough had left her. I, of course, cannot

cure the eye; it seems to me to be covered with a skin which an oculist

might easily remove.

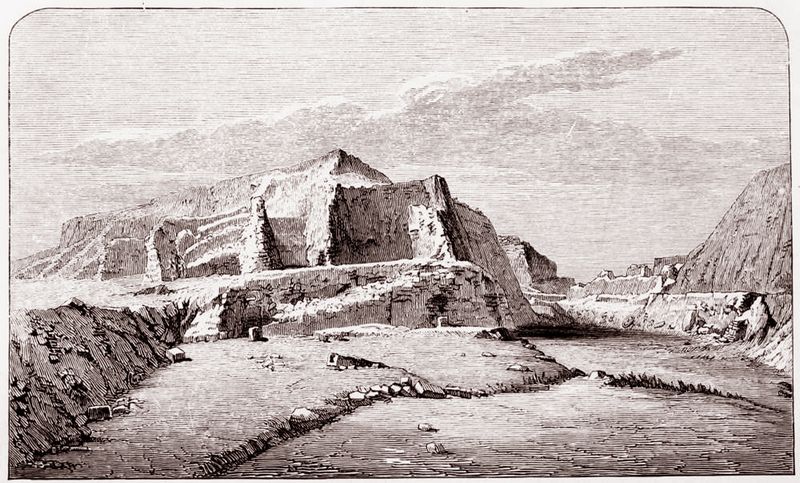

Plate VI: Trojan buildings on the north side, and in the great trench cut through the whole hill.

The girl had come on foot from Neo-Chori, a

distance of three hours, to thank me, and I can assure my readers that

this is the first case, in the Plain of Troy, in which I have received

thanks for medicines or medical advice; but I am not even quite sure

whether it was a feeling of pure gratitude that induced the girl to

come to me, or whether it was in the hope that by some other means I

might restore sight to the blind eye.

The heat has increased

considerably during the last few days; the thermometer stands the whole

day at 25° Réaumur (88¼° Fahrenheit) in the shade.{143}

Footnotes:

[134] See Plate XXII., No. 321.

[135] That is, belonging to the lowest stratum.

[136] Chapter VII., p. 121.

[137] See No. 380, on Plate XXIX.

[138] See No. 383, on Plate XXX.

[139]

Plate XXIX., No. 379. The front bears 4 卐; on the back are the emblems

described, which are shown separately in detail, and of which M.

Burnouf gives an elaborate description. (See List of Illustrations.)

[140] Plate XXVIII., No. 377; compare Plate XXVII., No. 367.

[141]

See Plate XXII., No. 328; the depth (14 M.) deserves special notice.

The wheel-shape, which is characteristic of the whorls in the lowest

stratum, is seen at No. 314, Plate XXI.

[142] Chapter IV., p.

84. See Plate XXII., No. 326, from the Atlas of Photographs, and Plate

XLVIII., No. 482, from M. Burnouf’s drawings.

[143] Plate XXX., No. 383.

[144] Page 83, and Plate LI., No. 496. This is one of the inscriptions examined by Professor Gomperz. (See Appendix.)

[145]

See Cut, No. 81, and Plate XXVII., No. 369. The latter is an

inscription, which Professor Gomperz has discussed. (See Appendix.)

[146] Iliad, VI. 168-170:—

Πέμπε δέ μιν Λυκίηνδε, πόρεν δ’ ὅ γε σήματα λυγρά,

Γράψας ἐν πίνακι πτυκτῷ θυμοφθόρα πολλά,

Δεῖξαι δ’ ἠνώγειν ᾧ πενθερῷ ὄφρ’ ἀπόλοιτο.

“But to the father of his wife, the King

Of Lycia, sent him forth, with tokens charged

Of dire import, on folded tablets traced,

Which, to the monarch shown, might work his death.”

[147]

Chapter IV., see p. 83-84. Though not Phœnician, these are Cyprian

letters, and they have been discussed by Professor Gomperz, who found

in this very whorl his experimentum crucis. (See Appendix.)

[148] Chapter IV., p. 87.

[Continue to Chapter 10]

|

|