|

Chapter 3

On the Hill of Hissarlik, November 3rd, 1871. {75}

MY

last communication was dated the 26th of October, and since then I have

proceeded vigorously with 80 workmen on an average. Unfortunately,

however, I have lost three days; for on Sunday, a day on which the

Greeks do not work, I could not secure the services of any Turkish

workmen, for they are now sowing their crops; on two other days I was

hindered by heavy rains.

To my extreme surprise, on Monday, the

30th of last month, I suddenly came upon a mass of débris, in which I

found an immense quantity of implements made of hard black stone

(diorite), but of a very primitive form. On the following day, however,

not a single stone implement was found, but a small piece of silver

wire and a great deal of broken pottery of elegant workmanship, among

others the fragment of a cup with an owl’s head. I therefore thought I

had again come upon the remains of a civilized people, and that the

stone implements of the previous day were the remains of an invasion of

a barbarous tribe, whose dominion had been of but short duration. But I

was mistaken, for on the Wednesday the stone period reappeared in

even{76} greater force, and continued throughout the whole of

yesterday. To-day, unfortunately, no work can be done owing to the

heavy downpour of rain.

I find much in this stone period that is

quite inexplicable to me, and I therefore consider it necessary to

describe everything as minutely as possible, in the hope that one or

other of my honoured colleagues will be able to give an explanation of

the points which are obscure to me.

In the first place, I am

astonished that here on the highest point of the hill, where, according

to every supposition the noblest buildings must have stood, I come upon

the stone period as early as at a depth of 4½ meters (about 15 feet),

whereas last year, at a distance of only 66 feet from the top of the

hill, I found in my cutting, at the depth of more than 16 feet, a wall,

6½ feet thick, and by no means very ancient, and no trace of the stone

period, although I carried that cutting to a depth of more than 26

feet. This probably can be explained in no other way than that the

hill, at the place where the wall stands, must have been very low, and

that this low position has been gradually raised by the débris.

Further,

I do not understand how it is possible that in the present stratum and

upon the whole length of my cutting (which must now be at least 184

feet) to its mouth, that is, as far as the steep declivity, I should

find stone implements, which obviously prove that that part of the

steep side of the hill cannot have increased in size since the stone

period by rubbish thrown down from above.

Next, I cannot explain

how it is possible that I should find things which, to all appearance,

must have been used by the uncivilized men of the stone period, but

which could not have been made with the rude implements at their

disposal. Among these I may specially mention the earthen vessels found

in great numbers, without decorations, it is true, and not fine, but

which however are of excellent workmanship. Not one of these vessels

has been turned{77} upon a potter’s wheel, and yet it appears to me

that they could not have been made without the aid of some kind of

machine, such as, on the other hand, could not have been produced by

the rude stone implements of the period.

I am further surprised

to find, in this stone period, and more frequently than ever before,

those round articles with a hole in the centre, which have sometimes

the form of humming-tops or whorls (carrouselen), sometimes of fiery

mountains. In the last form they bear, on a small scale, the most

striking resemblance to the colossal sepulchral mounds of this

district, which latter, both on this account and also because stone

implements have been found in one of them (the Chanaï Tépé) belong

probably to the stone period, and therefore perhaps to an age thousands

of years before the Trojan war.[92]

At a depth of 3 meters

(about 10 feet), I found one of these objects made of very fine marble:

all the rest are made of excellent clay rendered very hard by burning;

almost all of them have decorations, which have evidently been

scratched into them when the clay was as yet unburnt, and which in very

many cases have been filled with a white substance, to make them more

striking to the eye. It is probable that at one time the decorations

upon all of these objects were filled with that white substance, for

upon many of them, where it no longer exists, I see some traces of it.

Upon some of the articles of very hard black clay without decorations,

some hand has endeavoured to make them after the clay had been burnt,

and, when looked at through a magnifying glass, these marks leave no

doubt that they have been laboriously scratched with a piece of flint.

The

question then forces itself upon us: For what were{78} these objects

used? They cannot possibly have been employed in spinning or weaving,

or as weights for fishing-nets, for they are too fine and elegant for

such purposes; neither have I as yet been able to discover any

indication that they could have been used for any handicraft. When,

therefore, I consider the perfect likeness of most of these objects to

the form of the heroic sepulchral mounds, I am forced to believe that

they, as well as those with two holes which occurred only at a depth of

6½ feet, were used as Ex votos.

Again, to my surprise, I

frequently find the Priapus, sometimes represented quite true to nature

in stone or terra-cotta, sometimes in the form of a pillar rounded off

at the top (just such as I have seen in Indian temples, but there only

about 4 inches in length). I once also found the symbol in the form of

a little pillar only about 1 inch in length, made of splendid black

marble striped with white and beautifully polished, such as is never

met with in the whole of this district. I consequently have not the

slightest doubt that the Trojan people of the stone period worshipped

Priapus as a divinity, and that, belonging to the Indo-Germanic race,

they brought this religion from Bactria; for in India, as is well

known, the god of production and of destruction is represented and

worshipped in this form. Moreover, it is probable that these ancient

Trojans are the ancestors of the great Hellenic nation, for I

repeatedly find upon cups and vases of terra-cotta representations of

the owl’s head, which is probably the great-great-grandmother of the

Athenian bird of Pallas-Athena.

With the exception of the

above-mentioned piece of silver wire and two copper nails, I have as

yet found no trace of metal in the strata of the stone period.

As

in the upper strata, so in those of the stone period, I find a great

many boars’ tusks, which, in the latter strata, have without exception

been pointed at the end, and have served as implements. It is

inconceivable to me how the{79} men of the stone period, with their

imperfect weapons, were able to kill wild boars. Their lances—like all

their other weapons and instruments—are, it is true, made of very hard

black or green stone, but still they are so blunt that it must have

required a giant’s strength to kill a boar with them. Hammers and axes

are met with of all sizes and in great numbers.[93] I likewise find

very many weights of granite, also a number of hand-mills of lava,

which consist of two pieces about a foot in length, oval on one side

and flat on the other, between which the corn was crushed. Sometimes

these mill-stones are made of granite.

Knives are found in

very great numbers; all are of flint, some in the form of knife-blades,

others—by far the greater majority—are jagged on one or on both sides,

like saws. Needles and bodkins made of bone are of frequent occurrence,

and sometimes also small bone spoons. Primitive canoes, such as I

frequently saw in Ceylon, formed out of a hollowed trunk of a tree, are

often met with here in miniature, made of terra-cotta, and I presume

that these small vessels may have served as salt-cellars or

pepper-boxes. I likewise find a number of whetstones about 4 inches in

length and nearly as much in breadth, which are sometimes made of clay,

sometimes of green or black slate; further, a number of round, flat

stones a little under and over two inches in diameter, painted red on

one side; also many hundreds of round terra-cottas of the like size and

shape, with a hole in the centre, and which have evidently been made

out of fragments of pottery, and may have been used on spindles. Flat

stone mortars are also met with.

I also find in my excavations a

house-wall of the stone period, consisting of stones joined by clay,

like the buildings which were discovered on the islands of Therasia and

Thera{80} (Santorin) under three layers of volcanic ashes, forming

together a height of 68 feet.

My expectations are extremely

modest; I have no hope of finding plastic works of art. The single

object of my excavations from the beginning was only to find Troy,

whose site has been discussed by a hundred scholars in a hundred books,

but which as yet no one has ever sought to bring to light by

excavations. If I should not succeed in this, still I shall be

perfectly contented, if by my labours I succeed only in penetrating to

the deepest darkness of pre-historic times, and enriching archæology by

the discovery of a few interesting features from the most ancient

history of the great Hellenic race. The discovery of the stone period,

instead of discouraging me, has therefore only made me the more

desirous to penetrate to the place which was occupied by the first

people that came here, and I still intend to reach it even if I should

have to dig another 50 feet further down.

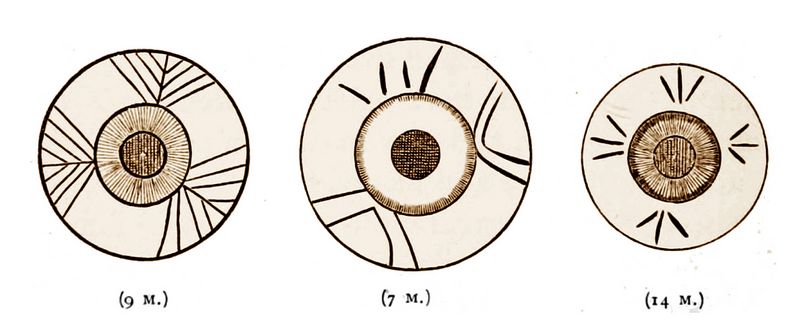

Figs. 42-44: Terra-cotta Whorls. No. 44 (at right) Is remarkable for the depth at which it was found.

Note.—The “Stone

Period” described in this chapter seems to be that of the third stratum

upwards from the rock (4 to 7 meters, or 13 to 23 feet deep); but the

description does not make this perfectly clear.—{ED.}

Footnotes:

[92]

For the further and most interesting discoveries which speedily led Dr.

Schliemann to recal this conjecture, and which have affected all

previous theories about the ages of stone and bronze, see the beginning

of Chapter IV.

[Continue to Chapter 4]

|

|