|

Chapter 2 (part 11)

Layer VI: the Mycenaean castle, continued (p.140).

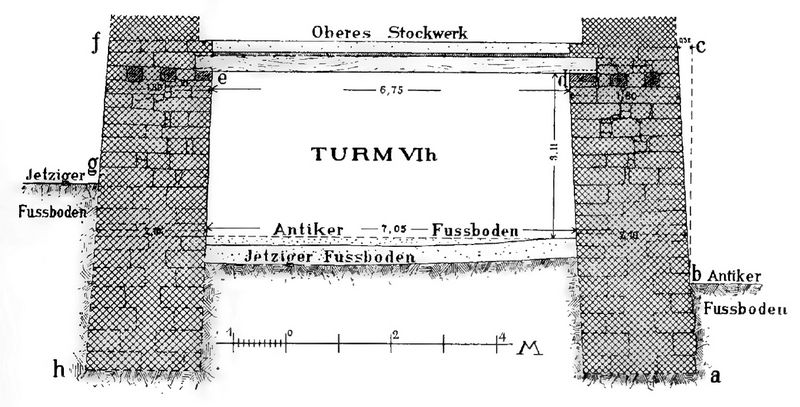

Several

holes preserved in the two side walls confirm the existence of a

horizontal wooden ceiling inside the tower. The cross-section laid

parallel to the castle wall, shown in fig.49, is intended to illustrate

their altitude and shape; a c is the northern, h f the southern side

wall. Within these walls, three holes can be seen at d and e, which

apparently once contained wooden longitudinal beams. In the drawing

they are made darker than the masonry surrounding them.

Fig.49: Cross section through the substructure of tower VI h.

Above the two

inner timbers were also strong deck beams, which reached from one wall

to the other. According to the holes that have also been preserved, one

of which can be seen on photo 19 in the northern side wall b, they had

a thickness of about 0.25 m square and clear distances of 0.62 m. Above

these deck beams we have planks or thin (p.141) crossbeams and reeds

and a layer of earth to add on top, because then the upper edge of the

ceiling just coincides with the surface of the substructure of the

castle wall.The lower, about 3m high interior of the tower So it only

reached up to the outside of the castle wall, while the upper room

extended over the castle wall and reached to its inner edge, where it

was closed off by wall a c (cf. the floor plan in fig.47) and two side

walls.

The three surviving walls of the upper storey are even

thinner than the stone superstructure of the castle wall, but their

thickness of 1.22 inches is perfectly adequate for tower walls which

were not directly exposed to enemy attacks. Their construction and

their state of preservation can be seen in the pictures in Figure 48

and photo 19 (on p. 128). On a larger (p.142) scale, its north-west

corner is shown as fig.50 below. The regular masonry of the tower wall

a stands out clearly from the younger one from the VIT. Layer

originating house wall b. While this one stands on rubble and ruins and

was apparently only built after the sixth layer had already been

destroyed, that one rests on the solid substructure of the castle wall,

of whose surface a small piece is still visible on the bottom left of

the picture.

The

gateway has a width of 3.20 to 3.35 m and is completely paved with

stone slabs. In the middle, under the pavement, runs a partly

uncovered, brick canal about 0.50 m deep and 0.30 to 0.40 m wide, which

was used to drain rainwater. It is doubtful whether the pavement and

canal really come from the time of the sixth layer, because the (p.143]

gateway was still used in the seventh and eighth layers; however, it

seems to me by far the most likely that it belonged to the layer VI castle. Fig.50: The northwest corner (a) of the VI h tower and a house wall (b) of the VII layer, seen from the north. The

tower room on the upper floor could be entered through a door marked b

in the ground plan; the basement can only have been accessed by a

wooden ladder from above. Whether another floor was built above the

upper floor and how the upper end of the tower was formed is completely

beyond our knowledge. Stones of a crenellated crowning or a cornice

have not been found here either.

Above,

we counted our tower VI h among the youngest constructions of the VI

layer, because it was added later to the castle wall and shows a very

(p.143) advanced construction. Although the VI g tower was built later

than the castle wall and has the same excellent construction in its

substructure, tower VI h must be younger. Because while the

remains of a superstructure made of mud bricks are still preserved on

tower VI g, tower VI h seems to have had a stone superstructure

from the beginning. Fig.51: The north-east tower VI g with later additions. In my opinion, we

can conclude this from the different wall thicknesses of the two

towers. VI g has wall thicknesses of about 4.50m on the east and south

walls and an average of 3m on the north wall, while VI h is about 3m on

the east side and only 2m on its southern and northern walls. Such

differences strongly attest to a difference in building material,

especially when we remember that the upper castle wall was about 4.50 m

thick when it was made of brick and only when it was renewed in stone

it became almost 2 m thick .

The largest and

still the most imposing among the towers of the VI layer is the

north-east tower VIg. We found it in 1893 and exposed it from the

outside, but we didn't know what it was hiding inside. It was not until

1894 that the almost 20m high layers of earth and rubble that filled

and covered its interior were removed. The ground plans on Plate V and

in Figures 51 and 52 show what came to light.

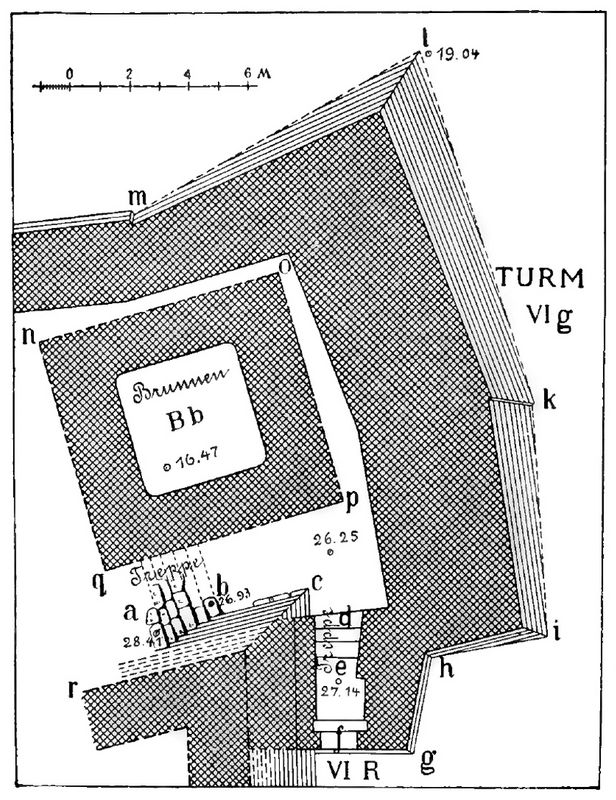

Fig.52: The north-east tower VI g in the VI layer.

The height of

the various walls and layers of earth is illustrated in Figure 53.

Inside the tower we found a large rock well B b of more than 4m square

and next to it a few steps of a staircase that once led to the higher

floor of the VI. up the castle. We were also able to determine that the

well in the VII layer was still in use and was surrounded by a new

wall.

After the destruction of the VII settlement, it filled

up with earth and soon disappeared under the ground. The VIII settlers

then erected their houses high above the buried well and built a

stairway next to the tower, which led to a new well Bh built outside

the tower.

Finally, in the IX or Roman stratum, a great

building, perhaps a mighty fire altar, was built still higher over all

the older ruins and masses of rubble. The new plateau was supported by

a mighty lining wall, the height and strength of which is particularly

evident in fig.53. Not all the younger ruins are drawn in fig.51;

the missing ones, as far as we have uncovered them, are shown on Plate

V. But (p.145) we will leave the younger buildings unnoticed for the time

being and turn to the remains of the tower belonging to Layer VI.

Fig.53: Section through the large north-east tower VI g and the well B b of the VI stratum.

Where

the eastern castle wall ends in the north at an almost right angle (at

c in fig.52), the large tower VI g was bluntly attached to the outside

of the castle wall and contained in its first part, reaching up to g h,

a gate f, the shape of which is taken from the figs.51 and 52 can be

seen.

The small widening immediately behind the entrance, at

the point where the word "Pforte" is written in fig.51, was intended to

accommodate a wooden frame for the closure of the gate. The corridor

behind is horizontal in its front part, in the rear it contains four

descending steps, only three of which were visible above floor VI. Its

left side wall is rectilinear, while the right side forms a broken line

and has a protrusion in its center that has created a recessed niche

just behind the door latch. Certainly, when the door was fully open,

this was intended to accommodate the only existing door wing and thus

prevent the width of the doorway from being reduced by the wing.

If

one descended the well-worked steps into the interior of the tower, one

saw the large well B b surrounded by a 2 m wide wall in front of one

and on the left the stairs b a. Although this is badly damaged and not

nearly as well made as the steps inside the gate, there can be no doubt

about its interpretation as a staircase. It mediated the communication

between the interior of the castle and the tower; on it one could

descend to the inside of the tower to fetch water or to get outside

through the gate.

The shape of the fountain can be seen from the

ground plans and from the section. The lower part has been cut into the

rock, the upper part is now built up with small stones. This masonry,

which can be seen in fig.53, comes in its present form from the VII

layer. Before that there was a thicker wall made of larger stones, of

which remains have been found in several places behind the younger

wall.

The part carved out of the rock is probably 7.50m deep,

so the bottom of the well was almost 10m below the floor of the VI

layer inside the tower. An exact measurement could not be made because

the well is still about 1.50 m high in its lower part filled with mud

and rubble. We wished to clean the whole well but had to refrain from

doing so because some of the upper walls and layers of rubble were in

danger of collapsing. With the help of an iron rod, we were therefore

able to determine the height of the remaining layer of mud at the

bottom and thus the depth of the entire well.

At its narrowest

point, the well in the rock has a width of 4.25 m square, meaning it is

a little wider at the top and bottom. I do not dare to decide whether

the strip, which makes up the narrowest point, was man-made or was

formed because the rock face in the rest of the well was weathered away

(p.146), but I prefer the second possibility. In fact, the strip

consists of a hard layer of limestone, while the remaining layers have

softer types of stone.

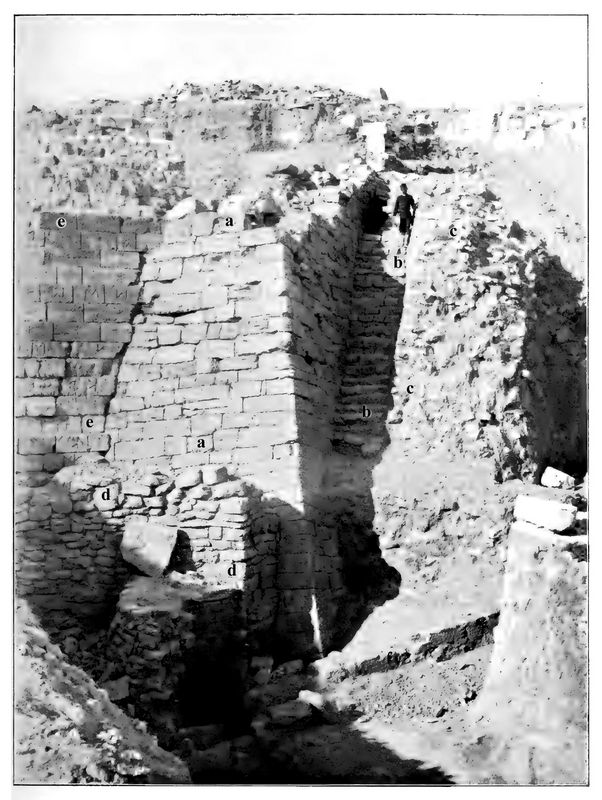

Photo 20: The large north-east tower g of the VI layer and its surroundings (1894).

Given the considerable width of the

shaft, which is quite unusually large for a scoop well, doubts may be

expressed as to whether it is really a water-supplying well and not

rather a large cistern for collecting rainwater. But I consider the

latter interpretation to be out of the question, because the shaft

actually goes down into aquiferous strata of rock, into the same strata

in which other wells of the usual form also lie. The strikingly large

width was chosen (p.147) so that as much water as possible could

collect in the well and a larger water supply was available in the

event of a siege.

We have no information about the upper end of

the well shaft. I assume that the walls enclosing it at the top, both

in the sixth and in the seventh layer, led beyond the corresponding

floors and carried a roof designed to cover the well.

To the

east and north of the fountain, the outer tower wall is not only

preserved in its stone substructure, but also in part in its

superstructure made of unfired bricks. It forms a mighty tower that

protrudes 8m in front of the eastern castle wall and is about 18m wide.

Its projection in front of the north wall cannot be determined because

we do not know for sure where the northern castle wall is connected to

the tower (cf. p. 116).

Photo 21: The large tower g of the VI layer, seen from the north-east (1894).

Although the entire outside of the

tower could not be uncovered because of the walls built in the VIII and

IX layers, there is no doubt about the external shape of the tower

walls; we know that about halfway down the east face (at k) was a ledge

with a re-entrant angle, and on the north face (at m) a similar ledge

with a re-entrant angle. It is not known why these broken lines were

chosen.

The stone substructure of the tower still ends at the

top in an almost horizontal surface, only slightly inclined inwards,

which is 27.75-28.00 m above sea level. It reaches down to the natural

rock, and as this appears here at different depths on the slope of the

hill, it has very different heights at the individual corners. At b,

where the rock is deepest, its height was almost 9m, near m only 3.50m,

and at the south end of the tower only about 2 m.

The type of

masonry can be seen from the three photos 20, 21 and 22, which show the

excellently preserved north corner from different sides. It is the same

corner which I have already described in words and pictures in the

book Troy 1893. At that

time, as photo 22 shows, the lower end was not yet known; it could only

be uncovered after we had partially demolished the Greek staircase c

and its side wall b in 1894, as has already been done in the other two

pictures. In photo 21 we see the north-east side of the corner straight

ahead, the other appearing as a line, broken line because of the

difference in their slope; on photo 20 both sides are visible at the

same time.

From the earlier description of the corner of the tower (Troy 1893,

p. 46 ff) it should be repeated here that its masonry is so excellently

joined and so well smoothed on the outside that we were extremely

astonished when we found it, and had concerns that such a wall could

have been of the Mycenaean period, i.e. to consider it to be of the

same age as the rough Cyclopean castle walls of Tiryns and Mycenae.

Photo 22:

The large tower g of the VI layer and its surroundings after the

excavation of 1893. a = tower of the VI layer; b and c = wall and

stairs of the VIII layer; d = retaining wall of the Athena temple

precinct of layer IX.

It

was only when several similar (p.148) brick buildings came to light

inside the castle, which, because of the pottery found in them, could

definitely be considered to be Mycenaean-era structures, that all

doubts had to be silenced. In reality, in Troy in the 2nd half of

the 2nd millennium a very excellent construction was usual. The size of

the stones and their good workmanship, the exact joint closure and the

excellent smoothing of the outside are clearly visible in our pictures,

despite the violent destruction of the castle and despite the sometimes

severe weathering of the stones.

[Continue to Chapter 2, part 12]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|