|

Chapter 2 (part 2)

4. Layer II, the prehistoric Trojan Castle.

In

contrast to the Layer I settlement, the buildings of which are only

partially uncovered and therefore only a little known, the IInd layer

has almost exclusively been excavated and examined by Schliemann. It

was at first considered the castle of the Homeric age and therefore

primarily formed the subject of his work and research. What was

preserved from their enclosure systems and its inner buildings during

the excavation has already been specified in the previous publications

and mostly discussed in detail. Part of the castle wall and the

southwest tower have experienced a description in the book Ilios (p. 42 ff. and 345 ff.). Then several buildings of layer II were treated in the book Troy (1882, pp. 59-99) due to my information from Schliemann. In the Reports

about the excavations of 1890, I myself discussed the preserved

buildings on pages 41-57. Some supplements are given in the book Troy 1893 (pp. 61-64).

Although

only a few new buildings have been added due to the excavations of 1894

and therefore our knowledge of the layer has only been expanded, a

detailed discussion of all of their buildings in this summary book

still seems to me to have all the more justification because the older

descriptions contain several errors and contradictions. In addition,

the ancient buildings from the third millennium can command our

full attention (p.50), especially since it is not just a few

incomprehensible walls, but also an entire castle complex with their

fortress walls, towers, magazines, and inner buildings.

The IInd layer is essentially identical to the "burned city", as Schliemann called and described it in his book Ilios.

Only he mistakenly counted the buildings of the IIIrd layer, those poor

huts that were only built over the destroyed buildings of the layer II

settlement. Now such a mistake is no longer possible, now the houses

and castle walls of layer II are layered easily from the older and

younger buildings as far as they are preserved.

Firstly, they

are almost exactly in one and the same height through all parts of the

hill, so that confusion with the higher or lower buildings is almost

excluded. Secondly, they have a peculiar design of them: their upper

walls consist of unbroken bricks and wood, their foundations and

substructures made of stones with earth mortar; In contrast, the upper

walls of quarry stones or cuboids also consist of the buildings of the

older and younger layers.

Thirdly, the structures of Layer

II can be recognized by the strong signs of fire that are visible

everywhere as witnesses of a huge conflagration. An almost 2m high

layer of yellow, red and black fire rubble covered all ruins that had

escaped the destruction. This rubble, which Schliemann referred to in

the book Ilios so often

and mistakenly as wood ash, consists in reality of burned (yellow),

half -burned (black) and very burned (red) clay brick residues, mixed

with soil, carbon, slag and other burned objects. It seems to have been

found everywhere, as far as the IInd layer is concerned; at the moment

it can only be seen on the standing cones in E 4, E 6 and F 4, as well

as near the castle wall remains

Schliemann's information about

the location of this fire layer and about the finds made in it may be

considered correct; at least we later found its details confirmed in

several places. He was only wrong by including the small stone houses

of layer III that were on the fire rubble to the "burned city". How he

came about this can be easily understood when looking at the

circumstances. When the settlers of the third stratum built their

apartments from small stones on the top of the rubble hill, they had to

have the foundations placed in the rubble to provide the walls. During

the excavation by Schliemann, various rubble masses were now found

between the tops of the walls, but between their lower parts was that

yellow, red and black burned rubble. Schliemann now calculated the

latter, as well as the numerous objects found therein, to belong to the

layer of the stone huts, and did not pay attention to the fact that the

rubble between the dividers of their walls could not be part of them,

but was absolutely older. (p.51)

In some places of the castle,

especially in the western parts, he had uncovered the correct walls of

the IInd layer, while in the eastern parts and in the middle the

remains of this layer were still buried under the younger ruins and the

rubble layer, and therefore have not yet been found. It was only

through the results of the excavations of 1882 that he was convinced of

his error, and now correlated in the book Troy

(1882, p. 59) the strong fire layer with its numerous finds properly to

the large brick buildings of layer II, and recognized in the higher

lying huts a poor village that was built on the rubble of the destroyed

town of layer II. I considered it my duty to explain this fact, which

has often given rise to misunderstandings and incorrect judgments.

The

Castle of the IInd layer is now exposed to almost its entire extent.

Only in the eastern parts of the hill some pieces below the younger

layers have remained unreachable. Even in the middle of the hill, small

parts of Megara II A and II B and the neighboring building are still

hidden in the untouched surrounding earth. Nevertheless, neither the

interior buildings nor the surrounding walls of the IInd layer castle

are fully known. Some of their buildings consisting of clay bricks had

already been completely destroyed in ancient times in the downfall of

the castle that their shape can no longer be recognized. Unfortunately,

others were destroyed by Schliemann in his first excavations without

being recognized as old brick walls.

Anyone who has ever dug

up walls from unbroken bricks will not blame the much-deserving

researcher from overlooking the brick walls, because he would

know from experience that special knowledge and great attention are

required in order to recognize such walls at all, and to distinguish

them from rubble masses around them. The places where the buildings of

the IInd layer have already been destroyed in antiquity, especially in

the northern parts of the castle, where the hill fell steeply and

caused a complete destruction of the walls. The buildings destroyed by

Schliemann were mainly located in the middle of the castle and mostly

went under in the production of the great north-south trench.

Fortunately, the floor plans of the destroyed buildings can be

supplemented with some certainty from the remnants still preserved.

As

a whole, the preservation of the buildings of the IInd layer is

sufficient to at least restore a large part of the castle wall with

their gates and also part of the inner courtyards with their buildings.

However, there is no uniform castle plan, rather you can see several

castle walls and several buildings. Already during (p.52) the

excavations of 1879 and 1882, it had been observed that there were

multiple conversions both the ring wall and the inner building. In

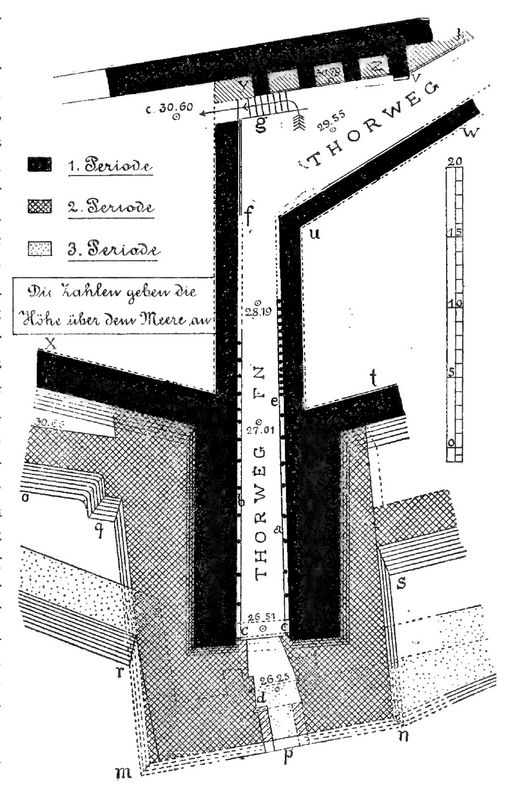

1890, three different periods were significantly differentiated. The

castle had experienced an expansion twice and at the same time an

almost completely conversion of the interior. In the plan of the report

on the excavations of 1890 (repeated in our photo 3 on p. 16), the

attempt was made to illustrate the development of the castle in the

course of the 3 periods.

Since these conversions took place

without significant increase in the inner floor of the castle, only the

foundations could be preserved from the buildings of the older periods.

In contrast, the preservation of the older systems, at least in the

south and east, was better seen in the castle wall and the gates,

because the conversion was associated with an expansion of the castle

circumference. The entire substructure of the older ring wall remained

here and was covered by the new wall built in front of it. While we can

easily distinguish and discuss the older period at the castle wall, the

knowledge of the older floor plans is very difficult for the interior

buildings, owing to the lack of all upper walls and even many

foundations. We therefore have to limit ourselves to the buildings of

the interior to describe the buildings of the latest period and to

mention the remains of the older buildings. At the castle wall,

however, we can discuss the individual walls in their historical order.

The

castle walls of all three periods are consistent in that they consist

of a substructure of limestone and earthen mortar, on which an upper

wall of mudbrick stood, and in part still stands. The lower wall is

more or less heavily sloped and extends to the inner floor of the

castle. It is a retaining wall with only one outward-facing facade. Its

stones, even those of the facade, are almost unworked.

The

inner boundary of the wall was always underground and only shows a

regular construction at the top. The core of the substructure is

assembled without care from completely unworked chunks of stone. Earth

is used to bind the stones, but there are also walls in which no mortar

seems to have been used at all. The strong embankment was due to the

small size of the stones and the poor quality of the masonry. At a

height of 1 m, it is between 1.00 and 0.50 m, so it is big enough that

you can climb up the wall without difficulty. You don't even have to

look for particularly large holes in the joints to insert your feet,

but can climb the protruding strips of the individual stone layers

almost like climbing a staircase.

It would be incorrect to

conclude from this that the wall could not have been a fortress wall;

on the contrary, due to the small size of the stones used, the strong

slope could not be avoided. The retaining wall would undoubtedly (p.53)

have yielded to earth pressure and fallen over if the outside had not

been sloped. Also, an unbanked wall could easily be brought down by the

attacking enemy by removing the lower stones. The inconvenience that

the wall could be climbed was completely eliminated by giving the wall

a superstructure made of mud bricks with a vertical outer side. If an

attacker had climbed up the sloping substructure, he was in a bad

position on the vertical brick wall: he could easily be thrown down by

the defenders standing on top of the wall, without being able to resist

himself.

Unsloped or slightly sloped fortress walls can only

be built of unworked stones if the individual stones are of such large

dimensions as the blocks of the Cyclopean walls of Tiryns or Mycenae.

Such huge stones were either not available to the builders of the II

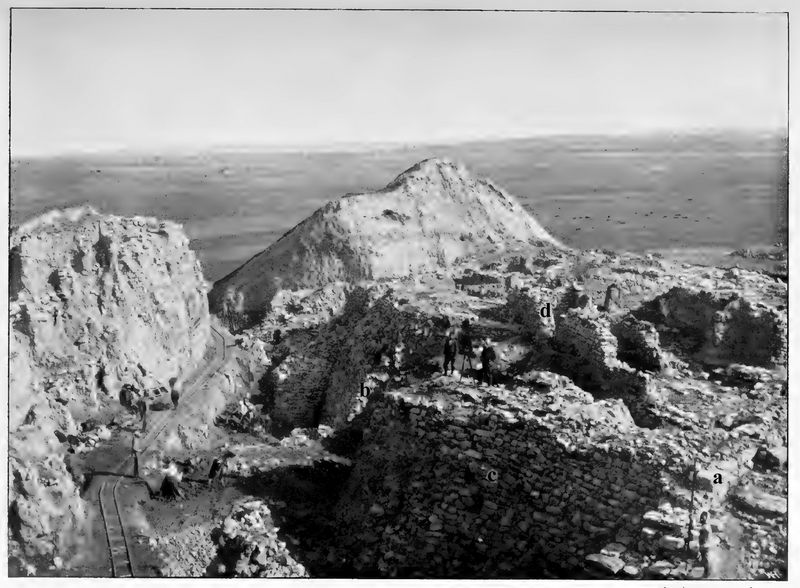

Troy Castle or were considered superfluous. Photo 6 gives a good idea

of the substructure of the castle wall. You can see the western wall

from the gate EM to the western tower FH.

Photo 6: Southwestern castle wall of the IInd layer (a-c) and house walls of younger layers (d).

The

actual defensive wall was the brick upper wall. It had been placed on a

stone foundation so that it could not be reached by the earth's

moisture, nor easily undermined or destroyed by the attackers standing

on the ground floor. The height of this substructure depended on the

height of the slope on which the wall was to be erected, and varied

between 1.00 m and 8.50 m at the various points of the castle. On the

north side, where the wall has been completely destroyed, the height of

the substructure may have been even greater. The height of the brick

superstructure is unknown and, as far as I can see, cannot be

determined in any way. We only know that it was considerably higher

than 3m, because the eastern brick wall still reaches that level in

places, and yet large amounts of rubble lay before it. As the upper end

of the upper wall we may perhaps assume a gallery covered with wood and

a horizontal earthen covering; at least the strong burning of the upper

part of the wall indicates the presence of many wooden beams.

The

substructures of the three different Castle Walls II are best preserved

in squares C 6 and D 6, as can be seen on Plans III and IV, as well as

in the section on Plate VIII. The wall of the first period is the

innermost one and is shown to be the oldest wall, later no longer

visible, because it goes under the gate EM; so it was already destroyed

when this gate was built.

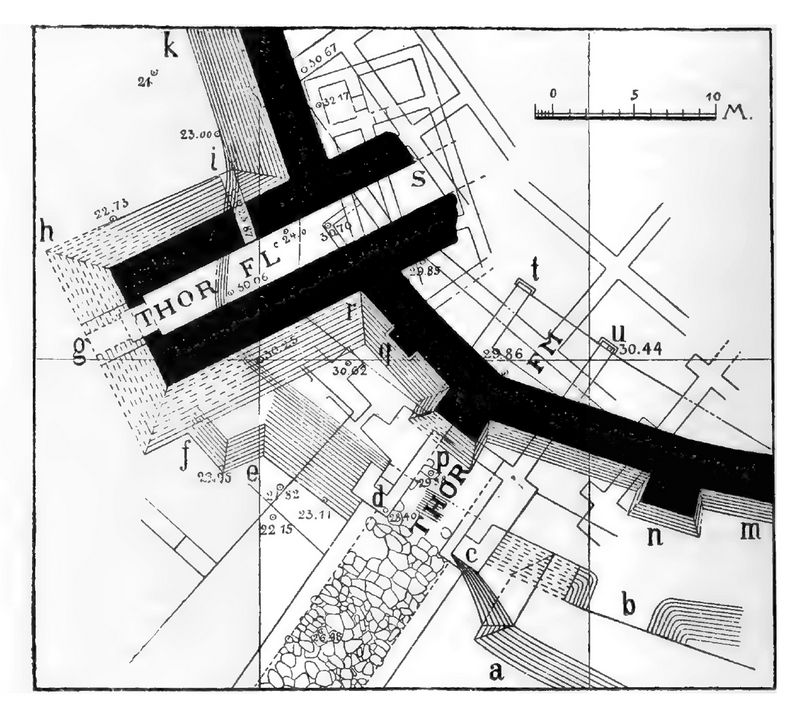

Fig.10 attempts to illustrate its

course in the south-western part of the castle. In this drawing it is

laid out entirely in black, while all other walls are left white. Now

about 2.70 m wide at its upper edge, it widens considerably downwards

be (p.54), the embankment is almost 1 m by 1 m in height. It is still

provided on its exterior with tower-like projections, two of which are

found at a distance of 10.6 m.

Fig.10: Gate FL and the adjoining castle wall in the first period of Layer II.

The eastern one (n in Figure 10) has a

width of about 3 m and projects 2 m in front of the wall line, the

other p seems to have the same dimensions. Both are located exactly

where the wall itself makes a bend, so they are attached to the corners

of the polygon formed by the ring wall.

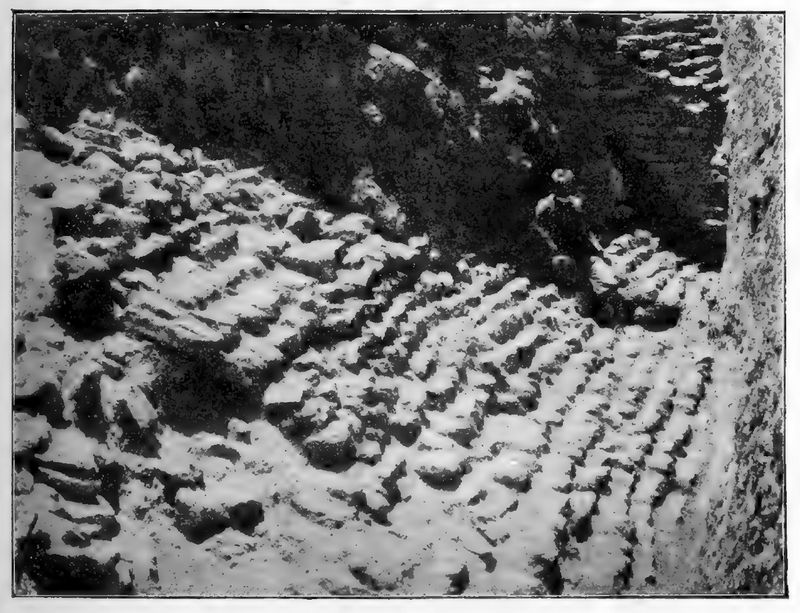

A photograph of the

tower n and the adjoining castle wall m is given in Photo 7. On the

left you can see the tower with its steep embankment, on the right the

substructure of the castle wall. Nothing remains of the brick

superstructure at this point, either on the tower or on the wall; it

was removed in ancient times when the younger wall was erected.

However, the fact that such a superstructure once existed everywhere is

confirmed by numerous remains of bricks that were found in the rubble

in front of the wall. (p.55) In another place (at r in fig.10) some bricks

are even preserved in their old position on the stone base.

Photo 7: Substructure of the southern castle wall (a-c) from the first period of Layer II.

The

course of the oldest wall of II cannot be traced around the entire

castle hill. On the west side it meets the younger castle walls and is

built over by them. At the north-west corner, in square C3, a piece of

wall has been found which, because of its steep slope, presumably

belongs to our wall range, if it does not have to be counted as part of

an even older circular wall.

Its appearance is illustrated in

fig.11, in which its steep slope is particularly visible. On the

northern slope of the hill, where the wall probably also collapsed with

the younger walls, it appears to have been destroyed in ancient times.

At the north-east corner, in squares G 3 and H 4, a heavily sloping

piece of wall is again preserved, which is drawn as a straight line on

panels III and IV according to the earlier plans, but in reality

appears to have a curvature. Due to the poor condition of the outside,

however, the size of the curvature could not be determined easily.

Since the section of wall is very similar in its (p.56) embankment and

the type of masonry to the wall uncovered in C 3, it must also have

belonged to the oldest wall section of Castle II.

Not

only the brick upper wall but also the upper part of the lower wall is

destroyed here. Our assumption given in Plans III and IV that the

substructure here still supported the upper brick wall in the later

periods of Layer II must remain an unproven assumption. The terrain

conditions only ensure that the older and the younger wall must have

stood here in approximately the same place.

Fig.11: Castle wall in C3 on the north-west slope.

To

the east the course of our wall has been traced by a small piece

unearthed in 1894 at G5 south of IX R. It lies in the continuation of

the wall remains uncovered further south-west next to the gate FO. The

total perimeter of the ring wall, as we have determined it with some

certainty for the first period of the II layer, is about 300m. In the

later periods it grows only a little and and not until the sixth layer

does it almost double in extent.

According

to the well-preserved substructures of towers found in the

south-western part of the wall, one might assume that there were towers

protruding from our wall on all other sides of the castle. But whether

they really existed must remain undecided; only a few small remains of

walls in C3 and H4 may belong to such towers.

In at least two

places the wall was breached by gates indicated on Plans III and IV;

the smaller FL lies in B 5 and C 5, the larger FN in E6 and E 7.

Although of different dimensions, they show the same general shape. The

gateway is built over by a mighty tower that protrudes far in front of

the wall line and gradually rises within the tower. It does not reach

the plateau of the castle in the line of the castle wall, as is the

case with the younger gates, but only further inside the castle.

At

gate FN the path has been uncovered and examined almost in its entire

length. It has the low pitch ratio of 1:15, so it was good to use for

wagons. In the smaller gate FL we only know a short part of the way.

Uncovering it completely would only have been possible at the expense

of important younger buildings, and therefore had to be avoided. There

is no stone paving in either of the two gates, only a simple screed of

clay covered the floor. The width of the path is 3.50 m at the larger

gate and gradually decreases towards the inside, at the smaller one it

is about 2.60 m in the uncovered part.

The floor plan of the

larger gate FN, which is repeated in fig.12 without the later

alterations according to Plans III and IV, is the best preserved. At

its front end, the gateway may have had a double closure (d and c, each

with two wooden gate wings, but the state of preservation of the walls

on the one hand and the later conversion to be mentioned (p.57) on the

other hand do not allow for a safe reconstruction. It is easy to

recognize only the lock c, which is 7.50 m from the end of the gate.

The complete burning of the projecting corners of the wall is due to

its major wood component. The traces of fire are still clearly visible here, 17

years after the excavation.

Fig.12: Floor plan of the FN gate in the 1st period of the 2nd layer.

If

we follow the ascending gateway towards the interior of the castle, we

first notice the standing marks of vertical wooden posts on the left

and right of the walls, which still enclose the path 2m high, which

once stood in front of the walls and are indicated in fig. 12 by two

rows of black dots.

They were apparently intended to support

the walls of the gateway, but also to support its ceiling and thus

presumably the floor of an upper storey. Set up at intervals of 1.30 -

2.10 m, according to their imprints in the plaster of the walls, they

must have been round, only slightly worked tree trunks. Their diameter

of about 0.20m is derived from the holes that were preserved in the

floor when they were found. At a distance of about 16m from the gate

lock the posts on the right side (at e) are placed much more densely,

and their small gaps are filled with rubble stone masonry. This is

probably due to the repair of a damaged piece of wall. Perhaps the side

wall had collapsed or was just about to collapse, and the presented

wooden wall lined with stones was then erected to gain greater strength.

(p.58)

In addition to the vertical timbers, horizontal wooden beams were also

installed in the side walls, the bearings of which are partly secured

by the corresponding cavities and partly by the remains of charcoal.

This large amount of wood and also the beams of the ceiling and the

superstructure provided the material for the great fire that destroyed

the gate building, and of whose magnitude the burnt masses of rubble

that filled the entire gate gave eloquent testimony. Even now it can

still be seen that the stones of the walls were burned in several

places by the fire which turned the lime and the clay used as mortar

and wall plaster into terracotta.

If we follow the gateway

further north beyond the Propylaion II C, which was later built over

it, we find in place of the vertical side walls on the left side an

embanked retaining wall and on the right a bend in the path and also

retaining walls on both sides. In any case, the change in the shape of

the side walls is related to the type of superstructure. As far as the

gateway was built over by a tower, it had vertical side walls supported

by wooden posts, as far as it was in the open air without a

superstructure, the wood was missing and the walls were laid out with

an embankment.

The transition from one type of construction to

the other was probably at f, i.e. opposite the point u, where the

right-hand side wall bends to the right. If the main path had climbed

in the same direction and with the same gentle incline to the height of

the second castle, it would have reached the plateau 4.50 m above the

entrance only beyond the center of the castle and thus cut through the

inner castle area in an unpleasant way. In order to avoid this, the

gateway, which could be used by carriages, was turned to the right (to

the north-east) and a stair-like ramp (g) was built for pedestrians, on

which the central square of the castle could be reached in a few steps.

After

the excavations of 1882, we had assumed that the gateway FN had been

built over with a tower about 18 m wide from the beginning. More recent

research, however, has confirmed the fact, first noticed in 1890, that

this large measure of latitude arose only in a more recent period

through the strengthening of the gate walls. As careful excavations

have shown, these side walls were originally only 3.50 - 4.00 m thick

and were later (probably in the 2nd period of the 2nd layer) doubled in

size by pre-built walls. It seemed to me that there were even two

reinforcements on the western wall. In our fig.12 and also in the plans

of Plates III and IV, the extensions of the large gate tower are

indicated by various drawings.

Only part of the smaller gate FL

of the same period (in square B5) has been excavated, namely the part

in front of the castle wall. Unfortunately, its state of preservation

is even worse than that of the larger gate. (p.59) What has been

preserved and revealed essentially agrees with the Thore FN, so that we

are entitled to add one after the other. We can therefore assume both a

front closure g (see Figure 10 on p. 54) and a long, gently sloping

gateway further inside the castle. Traces of the former have also been

found, but its dimensions could not be precisely measured.

We

have also been able to convince ourselves of the continuation of the

gateway towards the interior of the castle through excavations, without

being able to obtain more precise measurements. Only one thing is

better preserved in our gate, namely a side gate (i in Figure 10). It

is a sally port, only 0.8m wide, which was built in the corner between

the tower and the castle wall. It may be assumed that similar side

gates occur in Greek fortress towers. As we shall see, the gate

remained in place even in the more recent period and was provided with

an outer gate.

By analogy with this gate, one might assume that

the larger gate FN has a similar side passage. In fact, I found traces

of former openings on both walls of the gateway, which perhaps belong

to such sally ports. They lay between two vertical wooden posts and are

denoted by the letters a and b in our fig.12. Due to the poor condition

of the masonry, we unfortunately did not succeed in tracing the

corridors to the outside and uncovering them; its side walls collapsed

as soon as the rubble was removed. Already in the plan of the report

from 1890 (see our Photo No. 3 on p. 16) I indicated the beginnings of

these openings, which can be definitely ascertained, with small lines.

That the Thor FN had sally ports seems certain to me after this; but

whether there were two or only one must remain uncertain.

Although

the two gates FN and FL were completely sufficient for the small castle

of the first period of the II layer, I think it is possible that there

was a third gate at the north-east corner. The reason for this

assumption is, on the one hand, the fact that a wall BC was found

earlier in square H 4, which probably formed the retaining wall of a

ramp-like path that led up to the plateau of the IL castle along the

castle wall.

Fig.13 gives a photographic view of this

retaining wall. That it belonged to a ramp can be deduced from the

steep inclination of the horizontal joints. On the other

hand, the fact

that gates are secured in the east and northeast in the younger Castle

VI also makes the existence of a third gate for the II Castle seem

probable, especially since its other two gates also recur in Castle VI.

If our assumption is correct, the gate will have been in G3. However,

no traces of such a thing have been found there, because the brick

walls II M belong to a younger period; they will be discussed later.

Fig.13: The retaining wall BC in the square H 4, belonging to a ramp of the II level.

The

picture presented to us by the castle wall in the first period of the

second layer can be described in a few words. A wall of unfired bricks

rises on a heavily sloped stone base and surrounds the castle hill on

all sides. At intervals of about 10 m it is certainly equipped on the

south side, and perhaps also on the other sides, with towers 3 m wide

and 2 m deep; these also consist of bricks and a stone substructure. In

the west and south two powerful, 8 by 12 m wide towers far in front of

the wall line and contain the main gates of the castle on their front

sides and small sally gates on their side sides. Perhaps there is also

a gate in the north-east. The castle walls and towers are probably

provided with hall-like galleries at the top, so that the defenders can

position themselves in double lines, both at the hatches or windows of

the gallery and at the top of the horizontal roof of the hall.

[Continue to Chapter 2, part 3]

[Return to table of contents]

|

|