|

Chapter 1

HISTORY OF THE EXCAVATIONS OF TROY.

1. Schliemann's excavations from 1870 to 1890.

In

1868 Heinrich Schliemann set foot on the soil of Troas for the first

time. Inspired by the desire to find the site of Homer's Troy and

perhaps even to bring the ruins of the famous castle to light again

through excavations, he first visited the place in the Scamander

valley, where most scholars then placed ancient Troy, on the steep

Mountain above Bunarbashi village.

Here, at the end of the

18th century, the French traveler Lechevalier first looked for the

Homeric city and allegedly found it. Here, as will be described in more

detail in Chapter 9, famous geographers and strategists, of whom only

H. Kiepert, E. Curtius and Field Marshal von Moltke may be mentioned

here, later set out for Homeric Troy. Furthermore, in 1864, shortly

before Schliemann's first visit, excavations had been carried out by

the Austrian J. G. von Hahn, the results of which, according to the

book Die excavations on the homeric Bergamos by J. G. von Hahn, Leipzig 1864, seemed to dispel any last doubts about the correctness of the interpretation of Lechevalier.

Like

many travelers before him, Heinrich Schliemann also admired the

magnificent and comprehensive view that one enjoys from the steep rock

on the Scamander over the wide Troic plain and the distant sea with its

islands. But through small excavations he soon became convinced that

the famous castle of Priam could not have been located here because of

the low accumulation of rubble and the too young age of the preserved

remains of the walls.

He therefore visited a second place on the

Scamander plain, where Homeric Troy was placed by a few lesser-known

scholars, namely Hissaruk, which is closer to the sea and the ruins of

the Graeco-Roman city of Ilion.

The privileged location of this

place, on a hill at the crossing point of two fertile plains, the large

masses of rubble that had accumulated here over the course of thousands

of years, the striking correspondence of the landscape with Homer's

information about the location of the city, and finally, the

inscriptions and Ancient writers confirmed the fact that in Roman times

the city of Ilion had been located here, did not let him hesitate for

long: Only here could the place be where the Ilios of Homer once stood.

Apparently there had been settlements of various kinds here for

centuries. Here too, he was soon firmly convinced, the remains of the

old royal castle of Priam and Hector must have been preserved under the

ground and under the later building remains. To bring these fabulous

ruins to light and thus to fulfill a dream of his youth was the firm

decision he made on his first visit to Troas and soon put it into

practice. In the book Ithaka, der Feloponnes und Troja, which appeared shortly thereafter, he publicly announced his intention to excavate Homeric Troy on the hill of Hissarlik.

In

April 1870 we see him already at work. He broke ground on the

north-west corner of the hill and discovered a wall of Roman times,

shown on our plan III in square B4, but was forced by disputes with the

owners of the property, two Turks from Kum-Kaleh, to suspend the work

temporarily to stop and wait for the settlement of the ownership

situation.

After the Turkish government bought the western

half of the mound, excavations resumed in October 1871. This time Frau

Sophie Schliemann also took an active part in her husband's work. Again

the spade was used at the north-west corner in squares A4 and B4 and

the depths were dug beneath a Greco-Roman building. Several walls of

rough stone and mud-brick, numerous pieces of very simple ancient

pottery, and many stone implements have been brought to light, proving

to the lucky finder that there had indeed been settlements, as had been

suspected, from primeval times.

In addition, some Roman

inscriptions found in the top layer confirmed with full certainty that

the youngest walls belonged to the Roman city of Ilion. The older ruins

could therefore be attributed with the greatest probability to a

prehistoric Ilion. So Schliemann was able to say with full conviction

in his report of November 18, 1871 (Trojanische Antiquities,

p. 32): "If there ever was a Troy, and my belief in it is firm, it can

only have been here on the ancient buiding site of Ilion."

Schliemann's excavations in 1872.

Work

was discontinued during the winter and was not resumed until the

following spring (April 1872) with a larger number of workers. To the

east of the three working places, on the northern slope of the hill, in

squares D 2, E 2 and F2 of our Plan III, a large terrace was built and

driven into the hill. Schliemann planned a wide slant across the whole

hill in order to thoroughly explore the interior of the mass of rubble.

The location of this intersection, as well as the first site of

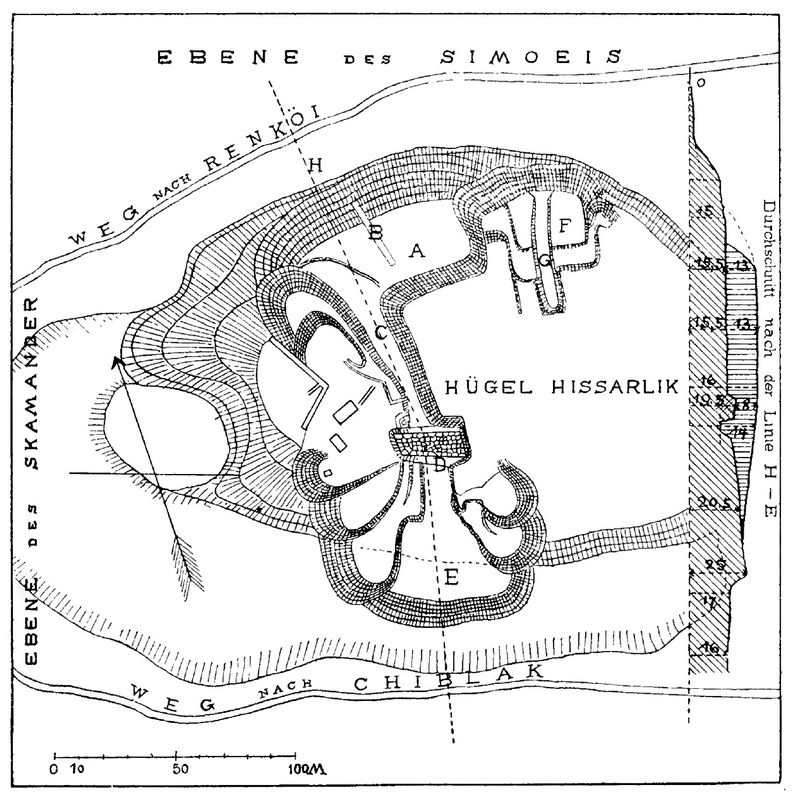

excavation, is given in the first plan published on Plate 116 of

Schliemann's Trojan Antiquities (1872).

On the right it is repeated here in fig.1, in a redrawing. The numbers 1 and 2 denote

Schliemann's houses at that time, 3-5 the excavations carried out up to

that point, and 6-7 the large planned cross-section. It was so broad

that almost a fourth part of the hill would have been destroyed if it

were executed.

Fig.1: Initial plan of the 1872 excavations at Troy (after Schliemann 1872).

At the northern end of the ditch (at 6) all kinds of ancient

finds were made: thong-suspended pottery vessels, spindle whorls, stone implements,

bronzes and many other objects. Old walls of various constructions also

came to light. What they looked like and what position they were in can

unfortunately no longer be determined, because during the first

excavations almost all the remains of the building were destroyed

without having been photographed and measured beforehand. We don't even

know what classes they belonged to. It can only be assumed that on the

northern slope of the hill the Roman border wall of the great sanctuary

of Athena was first uncovered and destroyed, for its continuation is

still preserved to the east and rests on the same hard, stoneless

rubble that Schliemann mentions in the report of May 2, 1872 (Trojan Antiquities, p. 83).

The plans of the excavation site, which were made in this and the following year and are published in the Atlas of Trojan Antiquities

(plates 117 and 214), do not show any walls at this point; they were

probably only drawn at the end of the campaign, when the northern

castle wall of the VI or Mycenaean layer can neither have been found

nor destroyed on the north side at that time, because not the slightest

trace of it was later discovered further west and east; it was

demolished in Greek times, and their material had been used in the

building of the walls of the city of Sigeion.

Fig.2: Final Plan of 1872 excavations at Troy.

In

order to create a large section through the entire hill as quickly as

possible and thus bring Priam's castle, which presumably slumbered deep

in the hill, to light the soonest, Schliemann also had a ditch started from

the south in D9 and DB, which should meet the large northern ditch. The

plan from the Atlas of Trojan Antiquities (Plate 117), which is

repeated here in fig.2, shows how excavations were carried out at that time.

A is the large platform on the north side, C is the northern end, and F

is the southern end of the great intersection. The individual terraces,

in which the excavation was carried out and the masses of earth were

heaped up, can be clearly recognized next to and in front of the

section by the arched heaps of rubble. The wide wall D lying in the

middle of the ditch, the so-called great tower, will be discussed in

more detail shortly.

A little south of this, Schliemann had to build

the ring wall of the VIth layer and the south-east corner of building VI

M (see Plate III), i.e. structures that really belonged to Homeric

Troy. He did in fact find the Maucrecke of layer VI M, but did not

recognize it as a ruin from the Homeric period. For in the Trojan Antiquities

article (p.82) we read: "Today the warden Photiadis has a magnificent

bulwark built of large, beautifully hewn shell limestone stones and

without cement or lime brought to light, which seems to me to be no

older than the time of Lysimachus. It is very much in our way, but it

is too beautiful and venerable for me to dare lay my hands on it, and

it shall be preserved. You can see it just to the left on panel 109."

Although

the photograph reproduced on this plate is very bad, the south-east

corner of the VI M building can be recognized with complete certainty

by its regular masonry and especially by the sharply worked corner.

Unfortunately, Schliemann's intention of preserving the beautiful

corner was thwarted by the Turks, for when he was later absent from

Hissarlik, the magnificent wall was demolished by the peasants of

Chiblak and used to build their houses. On the plan of the excavation

of Schliemann's 1873 excavations (our Fig. 3) it can still be seen, and

also on the later plan drawn by Burnouf (Ilios,

plate I; compare our Fig. 4) as Greco-Roman wall indicated. When I went

to Troy for the first time in 1882, it was no longer there

In June 1872, before the great cut through the whole hill was

finished, Schliemann began a second 30 meter wide cut further east on

the northern slope of the hill, namely in GH 2 — 3. On the plan in our

fig.2 is the new workplace marked with F. Since this spot was right

next to and below the Roman Temple of Athena, several parts and

sculptures of the temple were first found, among them the well-known

metope with a relief depicting Helios. Later the ashlar foundations of

the temple, insofar as they were still preserved, must have come to

light; however, they were demolished to allow the deeper structures to

be uncovered. Only a small piece of the foundation remains now.

Schliemann's excavations in 1873.

In

order to further uncover the "great tower" and the city wall to which

it belonged, excavations were resumed in February 1873 and continued

until June. The results of this third campaign can be seen on the two

plans N" 214 and 215 of the Atlas of Trojan Antiquities. I have repeated the first part of them in fig.3 below in a redrawing.

Fig.3: Plan of 1873 excavations at Troy.

First

he traced the "great tower" to the west and found the second level gate

(H in fig 3, and FM in C6 on Plate III). He interpreted it as a "Scaean

gate" (Altertume,

p. 272).

Beside and above the gate some houses of a younger layer are drawn on

the plan, some of which he had demolished in order to be able to

uncover the gate. In the walls drawn next to the gate he believed he

could recognize the "Palace of Priam" or the "House of the City Chief",

because in their vicinity he found the famous great treasure, which he

in the freedom of his discovery held to be the "Treasure of Priam". In

reality, however, as Schliemann himself later acknowledged, the gate

belongs to a different stratum than the house consisting of small

rooms, namely to the prehistoric castle II, while the house, which was

only built above the Ruins of the IInd layer, must be considered as

part of the far more modest settlement of stratum III.

The

great treasure did not belong, as Schliemann believed, to the IIIrd

Layer, but undoubtedly to the IInd and was most likely walled up in the

castle wall made of mud bricks. What Schliemann had earlier suspected

about the find spot he himself later retracted (cf. Troja 1882, p. 64).

We can conclude from the circumstances of the find that the treasure

was installed, as they are presented in the Antiquities

(p. 289) and have also been described to me several times by

Schliemann. The numerous objects of gold, silver, and copper were found

in a square heap atop the stone curtain wall and within a

four-foot-thick layer of red ash and calcined debris. Since later

excavations were able to establish that this red ash, so often

mentioned by Schliemann, was half or fully burned masonry made of mud

bricks and wood, which once stood on the stone substructure of the

castle wall and is still preserved in some places, so it can be

considered certain that the upper wall made of mud bricks at the site

where the treasure was found was still intact and that the great

treasure was built into it. Cavities could easily be created in the mud

brick wall, which was several meters thick.

Schliemann then

dug east of the "big tower" and found there a house consisting of

several rooms, in which a number of large pithoi came to light (see Ilios,

fig.8). It is not exactly clear to which stratum this house must be

ascribed. Based on the depth information and the good condition, I

believe it to be layer III, but it is not impossible that it belongs

to IV. An older, thicker wall underneath, which Schliemann then took

for an inner castle wall (Q in our fig.3 and b in fig.4), later turned

out to be one of the side walls of the older city gate of the 2nd layer.

Further

east he dug a long ditch to the south-east corner of the hill. It

should have hit the stately arched wall of the Mycenaean period (layer

VI) in this fine cut, as one might think. Despite its good condition,

he did not find it because the excavation did not go deep enough.

Only

the higher northern ashlar wall (T in fig.3) of the small Roman theater

B was reached, and taken to be part of the Greek ring wall of Lysimachus.

The foundation of the Propylaion to the Hiero of Athena (R in fig.3)

and the adjoining southern border wall of this Hiero were also

uncovered and erroneously declared to be a water reservoir (Antiquities,

p.224) and the foundation of the Temple of Athena. The latter

designation was prompted by a manuscript found here, in which the

sacred precinct of this goddess (to hieron) is mentioned. Schliemann translated hieron

as temple and therefore believed the building found earlier in the

north, which he had until then thought to be the temple of Athena , now

having to declare it a temple of Apollo, taking into account the Helios

or Apollo metope found there.

A third excavation took place on

the north side of the hill, where several houses of the IIIrd and IInd

layer listed on the plan N 214 of the Atlas

(our fig.3) were uncovered. However, given the discovery of the old

south-west gate and the great treasure, understandably, these

excavations on the north side soon receded into the background. On June

17 [1873], Schliemann completed his third Trojan campaign.

He

thought he had finished his work, because in his diary we read that he

was about to stop excavations at Ilion forever. In his opinion, the

Scaean gate, the great tower, the Trojan ring wall, the house of Priam

and the sacrificial altar of the Ilisian Athena had really been found,

and the Trojan question was finally solved.

How he conceived

the castle of Priam and the enlarged Greek castle of Lysimachus at that

time is shown by the two ring walls in fig.3, which are drawn in

different ways. What he believed to be Priam's Pergamum is essentially

what was later recognized as a prehistoric castle; only he drew the

eastern ring wall a little too far to the east. And what he regarded as

the castle of Lysimachos coincides, on the whole, with Castle VI of the

Mycenaean period, that is, with the real Pergamum of Priam; only here,

too, is the east wall pushed out a little too far. However, there are

not pieces of the VIth layer that he had connected to form a ring of

walls, but rather corners and sections of walls, most of which belonged

to different Roman buildings. Only wall O (fig.3) really seems to have been a

piece of the ring wall of level VI.

It was

therefore an inaccurate picture that Schliemann and his colleagues had

gained from the excavations of Homer's Troy and the city of Ilios in

Greek times. Fortunately the conclusion of the excavations in 1873 was

not definitive. The picture was soon corrected by new excavations.

After the publication of the Trojan Antiquities and the accompanying Atlas,

Schliemann had first carried out small excavations in Ithaca and then

moved to the castles of the Argive plains. In Tiryns he dug without

great success, but in Mycenae he found the fabulously rich royal tombs

inside the castle. No sooner had the results of this work been

published in the book Mycenae

than he was drawn back to Troy. We do not know whether he hoped to find

similar tombs in Troy as in Mycenae. In any case, we meet him again in

Hissarlik in the autumn of 1878 and can conclude from the great

preparations he had made for the new campaign (see Ilios, p.61) that he continued the excavations on a desired large scale.

Schliemann's excavations in 1878-9.

He

first dug again in the vicinity of the south-western gate and the

Priamos house, where he had previously found the great treasure, and

was also fortunate enough to discover some smaller "treasures".

Although the winter rains soon forced him to stop the fourth campaign,

but after a short break we find him again at work in March of the

following year (1879). For this fifth campaign he had the support of

Rudolf Virchow and E. Burnouf, the former director of the French

Archaeological Institute in Athens.The treasure digger of the first

Trojan campaigns had meanwhile become a scientific excavator who

considered it his duty to ensure careful professional examination and

accurate recording of the ruins and layers of earth uncovered with care.

We cannot go into detail here about the rich scientific results of the new excavations; this is reported in detail in the book Ilios,

published in 1881, to which Virchow and Burnouf had made valuable

contributions. With the help of these outstanding archaeologists,

Schliemann was able to distinguish and separate the various settlements

that left building debris and other remains on Hissarlik for

investigation. Seven layers lying one on top of the other were

recognized and he now called them seven "cities". He called the five

lowest prehistoric, the higher historic. Among the latter he

distinguished a Lydian settlement (VI) and an Aeolian or Greek (VII).

Of the prehistoric ones, the middle (III) was considered Homeric Troy.

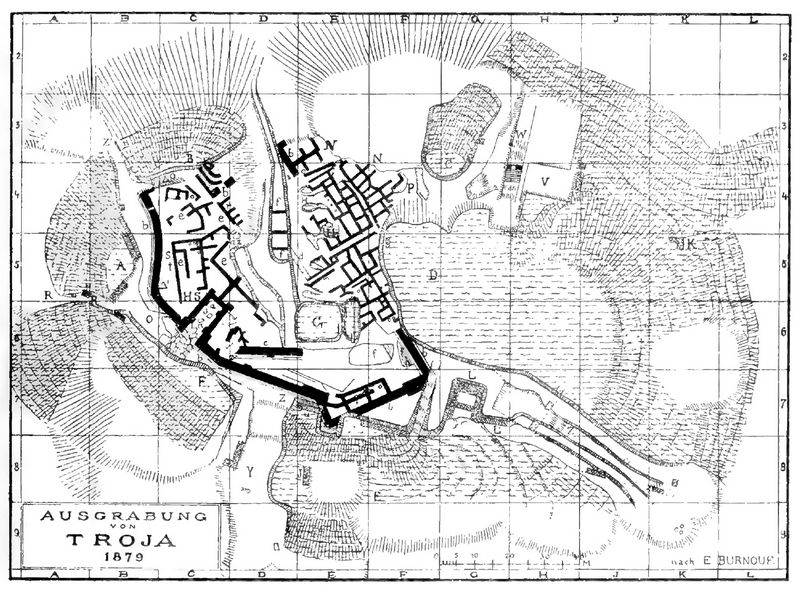

Instead of the earlier smaller plans, a new large plan drawn by Burnouf

(Ilios, Plate I) and several

valuable sections were published. I have reproduced the plan, in which

the prehistoric and historical ruins are distinguished by different

types of drawing, in fig.4. The prehistoric walls are all black, the

younger ones lighter.

Fig.4: Plan of 1879 excavations at Troy.

A

comparison with the older plan (fig.3) best shows us the advances that

are due to the excavations of 1878-1879. Almost the entire western half

of the old castle has been uncovered. The south-western castle gate (a)

is adjoined to the left and right by fortress walls (b), which can be

traced over a longer distance. The "big tower" of the earlier plans no

longer exists; in its place are now two separate castle walls (b and c)

entered, which had earlier erroneously been taken to be a single thick

wall. On the other hand, a large tower-like projection is now drawn a

little further to the southeast, which later turned out to be an older

castle gate.

The large north-south ditch, which we know from the

older plans, has been excavated a little further and shows several thin

walls (f) of the 1st or lowest layer, the oldest settlement in

Hissarlik, in its depth. East of this ditch we see a large

number of small chambers and corridors drawn, which, despite their

small dimensions and their simple construction, were considered by

Schliemann and his employees to be dwellings and streets

of Homeric Troy. In the eastern part of the hill only slight changes

from the older plan are to be noticed; little had been dug there.

Soundings were also carried out outside the Acropolis, on the adjoining

plateau on which the Roman city of Ilion once stood and where almost

the only remnants of the historical layers were found.

Schliemann

concluded from this that prehistoric Troy was limited to the Acropolis

hill and only the Hellenistic city of Lysimachus extended further over

the plateau. Of the work done in 1879, the investigation of the

numerous burial mounds that largely surround Ilion and that are laid

out on the mountain ranges by the sea were of particular importance.

These are the well-known tumuli, which in ancient times were believed

to be the tombs of Achilles, Patroclus and other Greek and Trojan

heroes. At that time, several of them were explored with a spade and

the objects discovered in them proved that they were partly prehistoric

and partly historical. Schliemann did not find any real graves in any

of them and was therefore inclined to take them all for cenotaphs.

The rich results of 1879 and their detailed publication in the book Ilios

seemed to have solved the Trojan question, and Schliemann's youthful

dream seemed to have been fulfilled. Nevertheless, he soon took up his

mission again. Immediately after the publication of the book Ilios

the tireless researcher on 1 March 1882 returned to Troy for a new

excavation campaign. Serious doubts had been expressed from various

quarters as to whether the small huts of the IIIrd layer, which was

described in the book Ilios

as the Homeric Troy, could really be the dwelling houses of King Priam

and his sons. Schliemann himself "had concerns about the expansion of

the city". It seemed to him impossible that "Homer could describe Ilios

as a large, well-built city with broad streets, when in reality it was

only a very small town". Those concerns were the ones who put the spade

back in his hand. Since the new excavation was primarily concerned with

examining the buildings as precisely as possible, he secured the help

of two architects, Mr. J. Höfler from Vienna and the present author.

Excavations in 1882-1883.

Digging went on for five months, and as the most important result of our work, it was possible to prove in the book Troy,

which appeared the following year, that those doubts in the main were

justified. The Tier III houses, which Schliemann and his associates had

taken for the houses of the royal castle in 1879, were just small

shacks built over the rubble of an actual tier II royal palace. When

the walls of the small houses were partially broken down, strong walls

and mighty rooms of a building complex appeared underneath them, which

we initially took for several temples because of their ground plan, but

soon recognized as the residence of the ruler and his family.

Unfortunately,

the work of the architects was very hampered by the Turkish Comraissar

and the rest of the Turkish authorities. Fearing that we architects

would like to record the modern fortifications of Kum-Kaleh, some six

kilometers from Hissarlik, we were forbidden to measure and draw within

the excavation field. Despite all the requests that Schliemann made to

the Turkish and German governments, it was not possible to reverse the

senseless ban. So it was not possible until the end of the excavations

to draw up a plan of the uncovered buildings (cf. Troy

1882, p. 13). Permission was only granted several months later, when

Herr von Radowitz had become German ambassador in Constantinople, and I

was allowed, under the supervision of two Turkish officers, to measure

and draw the floor plan of the castle that was published on Plan VII of

the book Troy, and in our fig.5 is repeated. Without this subsequent permission, the book would have had to appear without a plan.

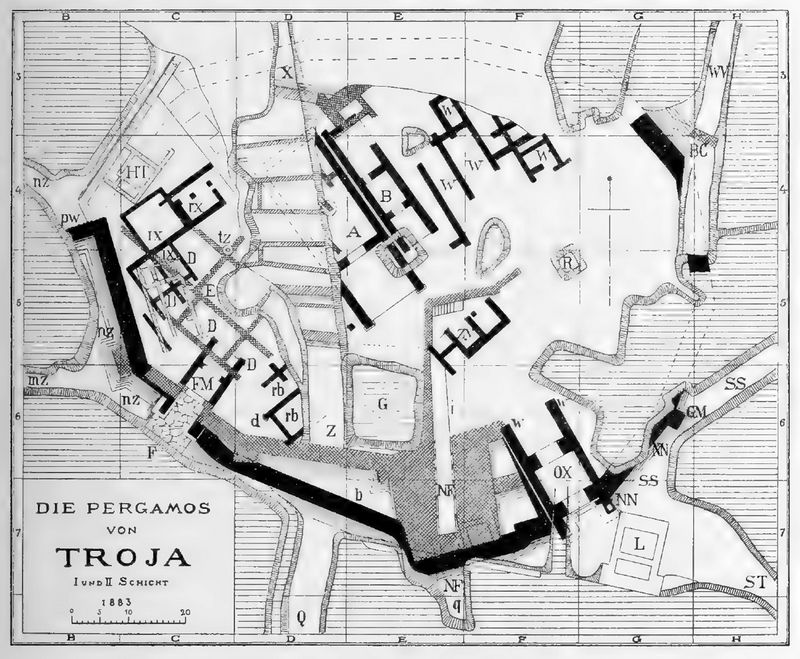

Fig.5: Plan of 1883 excavations of Troy Layers I and II.

Without

going into more detail about the results of the work in 1882, it may

only be mentioned here that first the ring wall of the second castle

was uncovered and examined over a larger stretch, and then an attempt

was made to draw its entire course into the plan based on assumptions .

In addition to the well-known west gate, two new gates of the castle

were found in the south and south-east, one of which belonged to an

older building of period II. Inside the castle we found several of the

uncovered buildings very well preserved.

It

was also possible to

supplement the ground plan here; they showed the plan of the simple

Greek temples with cella and pronaos and could therefore be either

temples or dwellings. Only later, when the Megaron of Tiryns Castle was

excavated, and thus the shape and location of the ruling house of the

heroic time had become known, the Trojan buildings could definitely be

declared residential buildings. In the case of other buildings, an

addition and identification was not possible because of the great

destruction. That the buildings inside the castle had undergone just as

extensive conversions as the castle wall and the gates, and that

therefore at least two periods had to be distinguished for them as

well, could be determined with certainty from the existing ruins.

In

1882 special attention was paid to the most recent buildings, those of

the Greek and Roman periods. We collected and drew the parts of the

great temple of Athena and some other buildings, the remains of which

were found partly in Hissarlik itself, partly in the various Turkish

cemeteries in the area; and recognized the gate building of the sacred

precinct of Athena and were able to see its ground plan and elevation

in the drawing. By conducting a small excavation, we also sought

information about the stage building of the large theater outside the

castle. Unfortunately, this architectural work was

also interrupted by the above-mentioned objection of the Turkish

commissar. Only a

few drawings that had already been made could therefore be published in

the book of Troy.

If,

in order to complete the overall plan of the excavation site and the

individual measurements and drawings, it would be highly desirable to

resume the excavations with a better permission, another reason soon

came up that made Schliemann and myself urgently obliged to continue

the work and investigations.

Since 1883, An artillery

captain, D. Ernst Bötticherm had published several essays and pamphlets

in which he tried to prove that on Hissarlik there were not still temples and castle walls, but only the remains of

a large cremation facility, a "fire necropolis". Although he had never

seen the ruins, he judged the various buildings with an enviable

certainty, called my plans figments of the imagination, and finally

went so far as to assert that the plan of the book of Troy, which

contradicted his theory, had been deliberately falsified by me.

Schliemann and I were alleged to have made large halls out of the small chambers

of the incinerator by demolishing intermediate walls!

Since we

were convinced that ßötticher would easily be disabused by appearances,

Schliemann decided to continue the excavations and to invite him to

visit. Bötticher complied with the request and appeared in Hissarlik in

December 1889 to examine the ruins with us in the presence of expert

witnesses. Such persons appeared at Schliemann's invitation: Major

Steffen from Berlin, known for his excellent maps of Mycenaean and

Attica, and the professor at the Technical University in Vienna G.

Niemann, who had directed the excavations of the Austrians in

Saraothrace as architect. After lengthy negotiations, of which a

protocol was recorded (Hissarlik-Ilion, 1890), Bötticher felt compelled

to withdraw his slander and in particular the accusation of distorting

the excavation results and to declare that he had not wanted to accuse

me of mala fides. However, when he refused to publicly ask Schliemann

and me for forgiveness for his frivolous and defamatory accusations, we

broke off the negotiations (1890 Report, p. 31).

While

Bötticher, having returned to Germany, resumed his incinerator theory

and tried to spread it, the excavations in Troy were resumed by

Schliemann and myself on March 1, 1890. At the same time, at

Schliemann's invitation, a larger international commission of

archaeologists met in Hissarlik and, after a thorough investigation of

the facts, declared that in no part of the ruins any signs of cremation

could be found, and that the plans published corresponded fully to the

actual condition of the ruins (1890 Report,

p. 6.). When Bötticher continued after this statement, not only to

declare all the ruins of Hissarlik to be a fire necropolis, but also to

slander Schliemann and his associates, we no longer deigned to answer

him. Even after Schliemann's death I have ignored his further attacks

and slanders, only publicly declaring that I consider it beneath me to

answer even a word.

Excavations in 1890.

Excavations which began in March 1890, were continued with

numerous workers and for the first time with the help of a field

railway until the end of July. Their scientific results are presented

in a preliminary report published by F. A. Brockhaus, Schliemann's last

work before his sudden, unfortunately much too early death. Immediately

after the end of the excavations, the report was written partly by

Schliemann himself and partly by me and was about to be printed when

Schliemann fell ill with an ear ailment after an operation and was

snatched from us by death on December 26, 1890 in Naples.

The

report appeared soon after with a foreword by the now widowed Sophie Schliemann. It

contained an exact new plan of the excavations that I had drawn up,

which is repeated on Enclosure N 3. A comparison with the older plan

(fig.5) clearly shows the results achieved in 1890. The castle wall of

the IInd layer on the east side of the hill was further uncovered; on

the whole south side three different walls of the second layer could

now be distinguished, which corresponded to three successive periods.

The castle was in each new period several meters to the south. A fourth gate was added to the three gates in the

south-west, which belonged to the first period of the IInd layer. Deep

excavations of the same three construction periods have been

discovered. Under the floor of the previously known buildings of the IInf

layer, the foundations of even older houses of the same layer were

preserved and joined together in some places to form understandable

floor plans. These older houses also had to be attributed to two

different periods.

Photo 3: Plan of 1890 excavations. (p.16)

A

special excavation that Schliemann had carried out outside the wall

circle of the IIL layer immediately in front of the southwest gate in B

6 was of decisive importance for the correct knowledge of all the ruins

dug up to that point. There he hoped to find the long-sought

royal tombs deep under the rubble on the rocky ground, because,

following the analogy of Mycenae, he considered it probable that the

inhabitants of Troy had buried their dead close to the gate.

At

the same time, this excavation was intended to serve to examine the

various layers of buildings on a smaller site that had been erected on

the hill above the IInd layer over the course of many centuries (report

1890, p. 57). There appeared, in fact, seven superimposed strata of

structures, which were individually drawn and photographed. After the

destruction of the second layer castle, seven different settlements

were built one after the other until the Roman period.

Even

then, in the middle of these building layers, it seemed to us that layer

VI was deserving of our special attention. At that point it contained

the remains of two large buildings which, by their dimensions, the

quality of their construction and the strength of their walls, were

distinguished from the buildings of all other strata. A ground plan of

one of these buildings could be published on p. 59 of the report,

showing the shape of a Greek temple or an old dwelling house, a

megaron.

The importance which we thought we had to ascribe to

the two buildings was increased by the fact that the objects which were

found in and near them can be dated to some extent and point to the

Mycenaean period. In addition to monochrome, mostly gray pottery, which

Schliemann had previously described as Lydian, several vases and vessel

fragments of the Mycenaean type came to light, i.e. objects that can be

attributed to around the second half of the second millennium BC. Such

vases had never been found in the lower layers.

We were then

able to conclude that those stately buildings must have existed at a

time when Mycenaean pottery was still common, so they had to be

ascribed to the second millennium BC or at the latest to the beginning

of the first. At the confirmation A. Brückner, at that time a

scholarship holder of the German Archaeological Institute in Athens,

whom Schliemann had summoned to study the vases in Troy on my behalf,

provided us with this fact very valuable help.

How could those

unexpected facts be explained? Did we find one or even two temples here

that were built in prehistoric times over the ruins of the second layer

after the destruction of the Homeric castle of Troy? Or could the two

stately buildings that were found be the inner structures of a larger

castle, whose ring wall was further to the outside, and had not yet

been found? Should one of the previously discovered walls previously

thought to be Greek be the castle wall of this VI or "Mycenaean"

layer? And if this was the wall, mustn't the 2nd layer be much older

than the Trojan War, and cede the honor of being Homer's Troy to the

6th layer? These important questions, which of course kept us busy and

are also indicated at the end of the report on the excavations of 1890

could only be answered by further excavations. Schliemann did not live

to see the solution to the problem; the questions accompanied him into

the grave unanswered.

2. The Work of 1893.

After

Schliemann's death, it fell to me, as his long-standing collaborator,

to continue the work in Troy and to bring about the solution of the

still existing and new questions by the spade. Frau Sophie Schliemann,

who had been a faithful companion of her husband during the work in

Troy and herself had dug up the "treasure of Priam" with him, kindly

made the money available for new excavations. She considered it her duty

to have the work completed in the spirit of her husband. We owe it to

Richard Schoene and Rudolf Virchow in particular that the excavations

interrupted by Schliemann's death could be resumed in the spring of

1893.

At my request, the Royal Prussian Ministry of Culture sent

Messrs. A. Brückner as archaeologist, R. Weigel as prehistorian and W.

Wilberg as architect to Troy to support me in the management of the

work and in the study of the finds. In a three-month activity, we tried

to solve the tasks assigned to us together.

We published the results of these new excavations and studies in the following year in the book Troy

1893. In it we were able to give the important information that the

sixth layer, in which the remains of the two stately buildings and the

vessels of the Mycenaean style had been found in 1890, actually

contained the ruins of a mighty castle complex of the Mycenaean period,

a castle which now could, with security, be declared from the Troy sung about by Homer.

We succeeded in discovering several other

large buildings and a mighty fortress wall of the VI stratum, and at

the same time in finding numerous objects which left no doubt as to the

dating of the VI stratum. In Mycenaean times there was a stately castle

on the hill of Hissarlik, the ruins of which had hitherto remained

unnoticed and buried, although some of them were in a better state of

preservation than the remains of the other strata.

The castle of

the second layer, which we had previously assumed with Schliemann to be

Homeric Troy, now had to be ascribed to an older prehistoric period.

Indeed, it was separated from the Mycenaean layer by three layers of

settlements and must therefore be considerably older than this. What it

lost in importance because it was no longer allowed to count as Priam's

castle, which Homer sang about, gained it to a greater extent because

it now became a pre-Homeric or prehistoric Troy and thus had to be

ascribed to a far distant time, a period from which we have no other

ruins, or at most very insignificant ones, in Europe and Asia Minor.

It

was a strange fate that Schliemann did not find the stately buildings

of the VI layer during his earlier excavations and did not recognize

their true meaning at the two places (in D8 and in K5) where he had

accidentally come across them. To the casual observer, it even seems

incomprehensible at first that Schliemann could excavate an older

castle and overlook a younger, higher-lying complex with massive walls

and buildings. But anyone who studies the ruins of Troy more closely

will soon understand this fact as a consequence of the peculiar terrain

conditions on the one hand and Schliemann's excavation method on the

other. On the north side of the castle hill, where the ring wall of the

sixth layer had been completely destroyed in antiquity, Schliemann had

made deep cuts in the slope. If the castle wall and the inner houses of

the sixth layer were still there, he would not only have found and

admired them, but probably also recognized them as Homeric buildings.

Unfortunately,

on the south side of the hill, its ditches did not go down deep enough

to find and recognize the castle wall. What he saw here of the circular

wall was only the superstructure, which had been badly damaged and

rebuilt; it was too insignificant to give Schliemann the idea that what

was left of a particularly stately castle lay here. A corner of the

inner building VI M had, however, come to light and, as we have seen,

aroused Schliemann's admiration; but because of its good construction

the wall had been ascribed to historical times. Also in the north-east

ditch in K 5 the upper part of the castle wall of the sixth layer was

cut through

but the ditch was so narrow that it was not possible to make a reliable judgment about the age, purpose and extent of the wall.

In

addition, until 1890 the excavations had been limited almost

exclusively to the core of the hill, because that was where the small

prehistoric castle had first been discovered and the treasures found.

In the middle of the mound, however, as we will see later, almost no

remains of the VI layer were preserved, and the outer parts and the

slopes of the mound, under which the buildings of the much larger

Mycenaean castle lay, were almost completely excavated remained

untouched. Only when a large area outside the IL castle was excavated

for the first time in 1890 did the two buildings VI A and VI B come to

light. Only they led to the discovery of the VI layer, the true Homeric

castle of Troy.

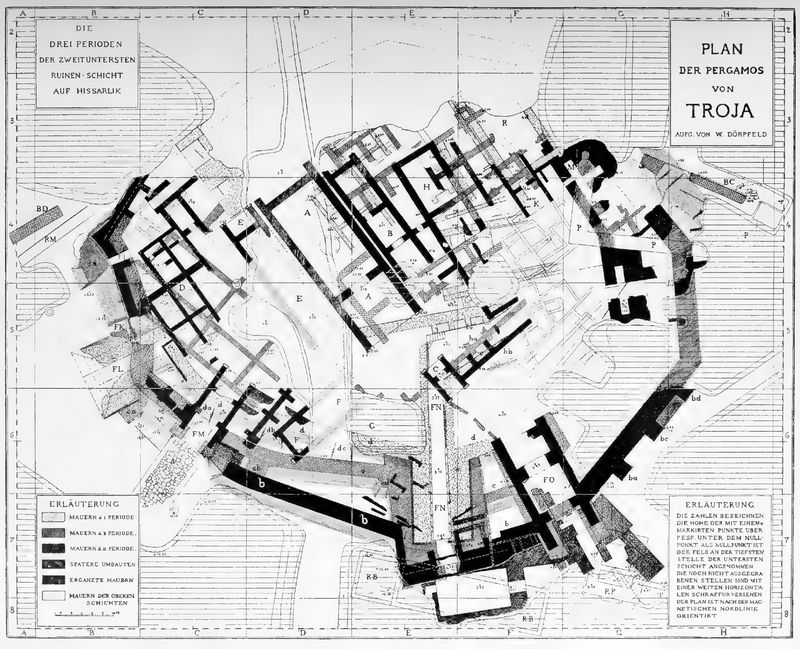

One need only glance at Plan I of Troy 1893

to see how much the picture of the ruins uncovered had changed as a

result of the 1893 excavations. It is true that the floor plan of the

layer II castle is only enriched by small additions in the north-west

corner

and in a few other places; but all around individual pieces of a new,

larger ring wall and inside several buildings of large dimensions have

been added, which form a large castle complex of the Mycenaean period.

And

above these venerable ruins the remains of Greco-Roman buildings are

shown on the plan, most of which belonged to the sanctuary of the Ilian

Athena. Schliemann's earlier assumption that in historical times there

was a temple of Apollo on the north-east corner of the hill and a

temple of Athena on its south side was not confirmed. Rather, it was

established that in Roman times the entire eastern half of the

Acropolis hill was occupied by the sacred area of Athena. The

Propylaion (in G7), discovered earlier, had provided the entrance to

this sanctuary. Parts of the foundations and several structural

elements of the temple itself had still been found. Also belonging to

the Roman period is a small theatre-like building (Theater B), the

ruins of which have been uncovered at the south-east corner of the

hill. Between the remains of the Homeric castle and the higher Roman

ruins numerous walls of Greek times were also found, which had to be

assigned to two different settlements. After the destruction of the

Homeric castle, there had been dwellings here at different times and

had been buried and built over when the great Hieron of Athena was

erected.

These results of excavations and investigations shed

the desired light on the history of the many settlements that had

formed one upon the other on Hissarlik Hill over the course of

thousands of years. The collaboration of architects, archaeologists and

prehistorians had solved some problems. The many buildings, as well as

the numerous finds made of stone, clay, metal and other materials had

been examined more closely and had thus made possible a fairly easy

separation and dating of the various settlements. The political history

of Ilion had also been further clarified by new marble inscriptions.

In the book Troy 1893

an approximate dating of the nine most important layers on the castle

hill of Ilion could be attempted (p. 86) and their construction,

destruction and expansion illustrated by a schematic cross-section (p.

35). We would have liked to have continued the excavations in the

summer of 1893, but the summer heat on the one hand and the consumption

of funds kindly granted by Mrs. Schliemann on the other hand forced us

to end the campaign, the first in which Schliemann had not taken part.

3. The excavations of 1894.

The

excavations carried out up to 1893 proved that more or less significant

remains of nine different settlements, which had existed in this

privileged place of the Skamander valley since ancient times, were

preserved on the Hissarlik hill. It was also established that of these

strata the five lowest (I - V) came from prehistoric times, that the

following (VI) belonged to the Mycenaean period sung by Homer and the

three higher ones (VII - IX) belonged to the younger Greek and Roman

epochs. The prehistoric settlements were carefully examined by

Schliemann's excavations, the Greco-Roman ruins were also thoroughly

explored, but we didn't know very much about the most important layer,

that from Mycenaean times. Although several interior structures were

found in 1890 and 1893 and the presence of a strong castle wall was

established to the east, south and west of the hill, the exact course

of the wall, its gates and towers were not yet known, and neither were

the interior structures studied as their importance required. It was

therefore urgently necessary to further elucidate the remains of the

important VI layer that had already been found by means of new

excavations and to seek out and uncover other ruins of this layer.

When

we left Troy after the completion of the work in 1893, it was with a

fervent desire to return as soon as possible and to complete the

excavation of the VIth stratum. Our wish was to come true

sooner than we dared to hope at the time. In August, 1893, in Potsdam,

I was permitted to make an oral report to His Majesty the German Kaiser

Wilhelm II on Troy and its excavations, and to present lithographs and

plans of the ruins that have been preserved. His Majesty not only

showed the keenest interest in the famous ruins, but also promised to

provide the necessary funds to continue the excavations. In fact,

during the winter of 1893/94 I received a letter from the German Reich

Chancellor with the highly gratifying news that His Majesty the Emperor

and King had given 30,000 marks from the funds for the excavations in

Hissarlik and for the publication of their results by the German Reich

and the Prussian State.

Through the kind mediation of the German

Embassy in Constantinople, the permission granted by the Sublime Porte

for 1893 was extended for another year, and so the excavations could be

resumed in the spring of 1894. So that the management and supervision

of the work can be carried out as professionally and thoroughly as

possible, and the observation and processing of all finds can be

carried out as carefully as possible, I again recruited several

collaborators for the various areas of archaeology. Unfortunately, A.

Brückner, who had been an archaeological member of our expedition in

1893, was unable to take part in the excavations for personal reasons.

The prehistorian M. Weigel was also unable to take part due to a

serious chest disease from which he had been suffering since 1893; we

even had the pain of learning of the death of this gracious and

talented collaborator just as we had begun the new dig. Only the

architect, W. Wilberg, was my assistant again from the earlier

collaborators. The two archaeologists H. Winnefeld and H. Schmidt stood

in for A. Brückner and the prehistorian A. Götze took part in the work

in place of Weigel. As commissar of the Ottoman government, the

official of the museum in Constantinople, Achmet Bey, was present

during the excavations; we are indebted to him for the proper

supervision of the work.

We hired two Greeks to oversee the

workers, Georgios Paraskevopulos from Olympia, who had already worked

as an overseer in Troy under Schliemann and had served me well in

almost all my excavations for many years, and Konstantinos Kaludis from

Athens, who unfortunately fell ill and has since passed away. The

photographer of the German Archaeological Institute in Athens, R.

Rohrer, was again persuaded to photograph the layers of earth, walls and

finds; he made several hundred recordings, a list of which will be

published at the end of this book. The average number of workers was

120. They were mostly the same people from the surrounding villages who

had worked in Troy under Schliemann. Some of them still bore the

Homeric names assigned to them at the time. One called himself

Agamemnon, another Odysseus, a third Achilles, and they proudly called

their "Here" when the list of workers was read out and these famous

names were called. Only a few Turks were among the workers, the great

majority being Greeks.

After the overseers had traveled to Troas

in mid-April to make all the preparations for the start of the

excavation, we ourselves arrived in Hissarlik on April 27th and were

able to start work immediately. During the months of May and June the

excavations continued uninterruptedly, but in July, as the summer heat

increased, not only did a great many workers fall ill with the fever,

but all my co-workers were seized with the nasty malarial fever. So we

were forced to stop digging in mid-July. We would have closed 8 days

earlier if we hadn't had the duty of bringing the excavations, which

were initially not to be resumed, to a temporary conclusion. With two

columns of workers we attacked the hill from the east and west,

followed the line of the castle wall from both sides and only reached

the main gate of the VI layer Castle. Without its exposure our work would

have been incomplete. Only when the gate was uncovered and the entire

line of the wall was determined were we allowed to put down the spade.

In

a 12-week strenuous work schedule, we had completed the task set before

us. Significant remains of the castle of the Mycenaean period, the

existence of which we had only suspected in 1890 and proved to be

certain by the excavations of 1893, now lay before our eyes. A mighty

ring wall with strong towers and several gates and a number of interior

buildings were brought to light. All the structures found were indeed

badly damaged, but the substructures that were preserved showed such

excellent construction and in some cases stood higher than we had ever

expected. In view of these stately ruins, especially the beautiful

retaining walls and the mighty castle wall, there was no longer any

doubt: these were the walls and towers that Homer sang about, here was

Priam's castle. Besides the ruins of the VI layer, we re-examined the

walls and soil layers of all the other settlements, which were proved

by the older and more recent excavations on the Hissarlik hill. What we

found here will be detailed in the next chapters. Only a brief overview

of the most important systems can be given here.

At

the top we had found the remains of large Roman buildings (IXth layer):

a temple, several theatres, colonnades and a gate building. They were

almost all destroyed except for the foundations. Their marble building

elements lay partly in Hissarlik, partly in the Turkish cemeteries of

the surrounding area. Among the Roman structures were two layers of

simple dwellings from the ancient Greek period (VIII and VII). Some of

its walls still stood several meters high; they had been buried during

the construction of the Roman acropolis without being completely

destroyed.

At a still greater depth we had discovered an older

layer (VI), which contained the ruins of a strong castle and certainly

belonged to the Mycenaean period, that is, to the time of the Trojan

War. Deeper still, in the central part of the hill, another three

layers of poor settlements (V, IV and III) had been found earlier, and

below these prehistoric villages lay that small castle (II) formerly

thought by Schliemann and myself to be Homeric Troy was, but had now

turned out to be an older prehistoric castle complex.

As long

as it seemed to be the only pre-Greek castle on the site of the later

Ilion, its claim to be the Troy sung about by Homer could not be

denied. But now that a Mycenaean castle had been found above it, it had

to relinquish its prerogative, but as an ancient, prehistoric castle of

Troy, it was allowed to claim our full interest. We therefore continued

to excavate and examine a small part of the second layer in 1894, a

work that was specially directed by A. Götze.

From an even

older settlement, level I, small building remains and many everyday

objects were found below the prehistoric castle. Since they were

particularly important for prehistoric science because of their old

age, we uncovered a small piece of this layer on the northern slope of

the hill.

However, our work was not limited to the castle hill

itself; We also undertook smaller excavations in several places in its

vicinity, namely within the later historical city of Ilion. First of

all, we wanted to look for remains of the sixth layer outside the

castle, in order to determine whether a lower city had existed

alongside the acropolis in Mycenaean times. Second, tombs of different

periods should be researched in the area. We did not hope to discover

the tombs of the Trojan rulers of Homeric times, for these can

undoubtedly be identified in the tumuli, in those numerous burial

mounds that lie on the hills around Troy and were thought to be tombs

as early as Homer's time. But we had every right to expect to find

simpler graves near the castle. As will be explained elsewhere, we were

not disappointed in this expectation.

Unfortunately, despite our

urgent wish, we were not able to excavate and examine some of the

tumuli in detail, because the Turkish government granted the requested

permission, but immediately revoked it. All our efforts in this regard

have been fruitless. Permission was not granted again, ostensibly

because the modern batteries were too close to the tumuli. We pointed

out that the two burial mounds which we had requested in the first

place to be excavated, namely Ujek-Tepeh (Ilios, p. 732) and Bcsika-Tepeli (Ilios,

p. 739), lie further from the batteries than Troy ourselves, but we

didn't have any success with that either. Admittedly, as we have

already reported, most of the burial mounds of the Skamander Plain had

already been explored by Schliemann, but the wells and ditches he had

dug for their investigation did not, in our opinion, reach deep enough

into the mounds. A more thorough excavation is urgently needed. It must

be reserved for a later time.

Although

the tasks we had set ourselves were essentially solved by our

excavations in 1894, the excavations in Troy have been brought to a

temporary conclusion, but they are by no means over for all time.

Excavations can and must still be made in the Greco-Roman city, the

ruins of which are preserved on the wide plateau next to the castle and

are still buried under the earth. Furthermore, the castle wall of the

VI layer on the south side must also be uncovered. Up to now we have

only freed its upper edge from the mass of rubble and verified through

a few shafts that it still stands several meters high along its entire

length. The Homeric castle would gain greatly if this stately wall

could be uncovered, in whole or at least in part, in its full height,

as we have done with the east wall. The fact that the south wall may

have been equipped with a tower that has not yet been found will be

explained elsewhere. Desirable work is also the construction of a later

retaining wall discovered by Schliemann on the north slope of the

castle hill and the complete excavation of the large well B b in the

north-east tower of the sixth layer.

One could also think about uncovering the unexamined part of

the VI layer in the squares E8 to G9 and when carrying it out one

should count not only on new buildings of the VI layer, but also on the

complete completion of the main entrance to the castle. However, I have

already stated elsewhere (Athen. Mittheil. 1894,

XIX, p. 392) that I consider such work to be neither necessary nor

desirable. It seems to me that it is our duty to leave untouched some

parts of the peculiar hill of Troy, which is so extremely important for

the study of antiquity, so that later generations, who are certainly

even more trained in the technique of excavation and even more careful

in observing the different things will be when we can control and

possibly improve our work through new excavations.

If the whole mound

is now excavated and the different strata do not lie undisturbed on top

of each other at any point, then any later investigation of the ruin

site and any control of our observations is made impossible for all

time. Already Schliemann, wrongly feeling this obligation, left some

cones of earth inside the castle where the younger strata lying above

the 2nd castle can still be seen and examined again, but on the one

hand these cones of earth are too small and in the course of the time

are gradually destroyed by rain, sun and wind, and on the other hand

these places are in the middle of the hill, where nothing or only very

little is preserved from the VI to VIII layers. We therefore thought it

necessary to leave a large area quite untouched on the edge of the

hill, where the upper strata still exist.

Leaving aside those smaller works that are easy to catch up

on, the great work of the excavation at Troy was essentially completed

with the excavations of 1894. The wish with which Schliemann first set

foot in Troas, to find and excavate the Homeric castle, has in fact

been fulfilled, more fully than could ever have been hoped for. On the

spot where the Roman city of Ilion stood with its large buildings,

ruins from the earlier Greek period, stately remains of Homeric Troy,

and many other ruins of even older settlements have been found. Priam's

castle has actually been given back to us, and in addition we have in

it a unique, extremely important ruin site for the study of the oldest

history of mankind.

Plate 2: 1894 excavations at Troy, showing personnel of the expedition.

Two

photographs of the excavations of 1894, which are published in the

appendices to this section, may give a vivid impression. Plate 2

shows the members of our expedition, the overseers and workers at one

of the uncovered buildings of Homeric Troy. Behind the people you can

see the beautiful retaining wall of building M, layer VI, made of large

stones and next to it simpler walls of the younger strata. In the

second picture, the adjacent Plate 4, some workers are shown in full

activity: on the east side of the castle hill, younger walls are being

uncovered over the Homeric castle wall. The excavated earth is brought

in by handcart and poured down the castle wall into small wagons, which

are then taken on rails to the edge of the hill. The castle wall and

its eastern tower can already be seen under the stones and masses of

earth.

Plate 4: The excavation of the eastern castle wall of layer VI in 1894 (p.24)

I

cannot close this chapter on the history of the excavations in Troy

without expressing the hope that a larger part of the lower city of

what later became Ilion will soon be uncovered, and that the tombs of

the ancient kings of Troy will also be examined more closely.

Wilhelm Dorpfeld.

[Continue to Chapter 2]

|

|