|

The Gigantomachy from the Pediment of the Ancient Temple of Athena on the Acropolis.

[Ath.Mitt. XXII 1897 pp.59-112]

In

the course of the past year (1895) in the Acropolis Museum in Athens a

monument of Old Attic sculpture was resurrected, which, almost

hopelessly shattered, had to wait longer than the other finds from the

Persian rubble to be restored: the Gigantomachy from the gable of the

old Athena temple. Despite major gaps, and despite the disfiguring

damage, this work impressively brings to mind the height that Attic

monumental art had already reached before the Persian wars, and most

welcomely complements the series of archaic individual works that have

come to light from the Persian rubble.

Since Studniczka had

discovered the first traces of this composition with fortunate

perspicacity in 1886, numerous new fragments had been added by the

final excavations of the Greek Archaeological Society at the castle.

The ordering and assembling of what was there, long begun, was

completed in the autumn of last year under the energetic care of the

General Ephorus of Greek Antiquities, Mr. Kavvadias. If Mr. Kavvadias

deserves general thanks for this, I also owe him a special personal thank

you for the liberality with which he allowed me to study the fragments

in detail, to monitor their composition and to publish my observations

and conclusions here. During the work I received the most gracious

support from the Ephoros of the Acropolis, Mr. Kastriotis.

[p.60)

The fragments of the Gigantomachy are scattered almost all over the

Acropolis, but have all been found in layers of rubble from the 5th

century; some in the backfill of the eastern half of the ring of walls,

most in the large heap between the south-east corner of the Parthenon

and the southern wall, or in the masses of rubble that were raised at

the same time as the southern foundation of the Parthenon, i.e. in the

actual Persian rubble. In the first-mentioned find area, in the

southeast corner of the castle, the head of Athena came to light as

early as 1864, during basic excavations for the construction of a

museum, together with the calf-bearer and some other archaic sculptures

[1].

In second place in 1882, along with

many others, was the piece that gave Studniczka the impetus for his

momentous discovery: the left shoulder of Athena covered with the

aegis, to which he attached the long-known and admired head of the war-like advancing goddess [2]. The number of fragments

assembled by Studniczka at that time of Athena as well as of several

strongly moved naked warriors - gods or giants - was significantly

increased by the further diggings at the same place [3], and finally

the Persian rubble provided a number of fragments and thus the proof -

if it was still needed - of the pre-Persian origin of the group. Far

removed from the head, Athena's lower right leg and many pieces of her

robe were found here [4].

The preservation of the fragments is

as excellent as that of the other sculptures originating from the

Persian rubble: hardly one or the other piece shows traces of

weathering, most of them had fresh (p.61) colors when they came out of

the earth, these are not completely extinguished even now. Few have

suffered from fire.

Finding the fragments of the pediment from

the mass of Archaic marble fragments was not very difficult, once the

important scale of the figures and the magnificent decorative work had

become clear through the pieces assembled by Studniczka. The material,

too, a coarse-grained, often blue-stained marble that tended to break

up in layers, gave an easily recognizable feature. So many fragments

were recognized right away during the excavations, others later, when

the fragments were arranged in the extension of the Acropolis Museum,

especially through the efforts of B. Sauer. A new careful examination

of the numerous fragments kept in the castle, which I undertook,

yielded only a small gleaning.

The merging of the rubble had

already been started here and there; here, too, B. Sauer made a special

contribution. Despite all this, the work didn't seem very promising at

first. If one remembered the enormous dimensions of the gable - about

20 m in length, 2 1/2 m in height - and then looked at this moderately

large heap of smashed limbs and almost unrecognizable large and small

chunks, one could scarcely imagine that something coherent could emerge

from it. As the work progressed, however, the fragments were gradually

distributed among a few figures and, with arduous attempts back and

forth, four figures grew together, into which the fragments merged

except for a small remainder.

The difficult and laborious

attachment of the fragments to one another is the work of the excellent

marble worker of the museum, P. Kaludis, who was so well proven in the

reconstruction of the poros groups of the Acropolis. The sculptor

Vitalis was called in to complete the figures, which was naturally

limited to a few parts necessary for their cohesion.

I. Description of the remains.

1. Athena (cf.

plate 3). The fragments of Athena are arranged in two large, connected

masses, which are only a few centimeters apart, but in such a way that

the posture of the whole figure is secured.

Plate III: Figures of Athena and giant, from pediment of the old temple of Athena.

The large fragment found in 1888 had long been attached

to the head and the left shoulder, which was covered with the aegi. A

wedge-shaped piece pushed into the gap between the two shoulder pieces

[5], which reveals the wide belt and above it the hem of the outer

garment. Two richly pleated corners of this garment, which fall below

the knee and which apparently correspond to the usual sloping coat of

the Archaic Koren in the castle, could be attached at the front [6]. At

the back was the part of the right gluteus already known to Studniczka

(No. 4 in his case), from which the position of the far receding right

thigh resulted

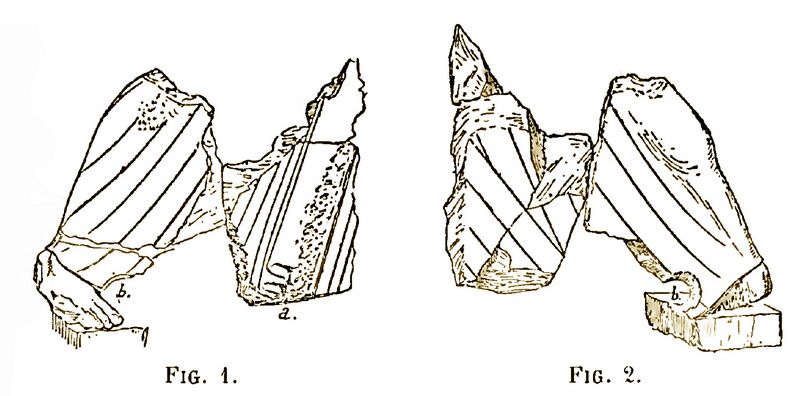

The second group of fragments is illustrated in

figs.1 and 2 in front and rear views. The fragment of the right

lower leg completes another one to the right, which belongs to the robe

hanging down between the striding legs. In front one sees the typical

wide central fold painted with a rich, now almost extinct meander, to

the left and right of it flat incised fold strokes, which converge

upwards towards the girdle (p.63). The back is treated much more

simply; in the flat surface roughly parallel to the front, some folds

are indicated by indented furrows of triangular cross-section. Four of

them, the extreme left ones, intersect at an acute angle with the rest,

apparently descending from the belt; they must emanate from the far

protruding left thigh.

Figs.1 and 2: Fragments of right lower leg of Athena.

The

position of the right lower leg is now given by the piece of the plinth

preserved under the foot; the piece of robe must be immediately on the

right because the thickness is exactly the same. How high it was to be

mounted was shown by the consideration that only a little is missing

under the large central bar on the front, so that the piece is probably

broken off just above the plinth. By placing it at the appropriate

height and matching the folds on both sides with those obtained on the

thigh, the fractures were made to fit exactly over a distance of 8 cm.

This was the connection between the upper part of the figure and the

lower one. For the continuation of the central fold upwards is

preserved on the cloak hanging down from the right breast, and the

breaks fit together for a short distance, but completely sharply. The

whole now reaches the stately height of 2m (without the 10-12 cm high

plinth). The left leg is unfortunately completely lost and had to be

supplemented as well as possible; his preserved attachment to the

gluteus and the hollow of the knee offered some clues for the (p.64)

production of the right thigh.

The overall impression of the

figure, as it now stands there, seems to me to confirm the correctness

of the composition and every examination of the individual leads to the

same result. Suffice it to say that the fold lines preserved on the

right gluteus merge perfectly with those on the back of the right lower

leg, and that the rivulets of rain-dissolved paint on the back of the

aegis are exactly vertical, as might be expected.

Unfortunately,

there is no new material available to supplement the arms. This much is

certain, that the right arm was raised high, the upper left arm greatly

lowered, and from the curvature of the aegis in the lowest surviving

piece it follows that the lower left arm stretched forward, not

sideways. After that, the position of the surviving left hand can be

determined roughly as assumed in the supplement. In any case, the staff

that the fingers enclose had a vertical direction; only by holding the

fist in this way can it be explained that the aegis hangs parallel on

the outside and inside of the hand. This is important for the

assessment of that staff, which is preserved in a short approach below

on the hand, above which was evidently made of bronze, as a large

borehole with verdigris spots on the edge teaches. Studniczka was

inclined to supplement this staff as a lance and found two

possibilities for explaining the striking phenomenon of Athena grasping

a spear with her left hand (p. 189): 'either the goddess snatched her

with her right hand swung her own weapon, with the other her opponent's

his, or she bore her spear into his body with both hands.' The first

assumption is contradicted by the position of the left hand, which

grips the staff but does not pull on it, the second by the strong

lifting of the right arm, clearly recognizable on the shoulder piece,

which can in no way be associated with the staff (p.65).

Moreover,

both assumptions leave unexplained why the thick seam of the aegis,

which is clearly expressed on the outside and inside of the hand, is

worked off on top of the fist. The reason for this cannot be that this

part was not visible; the whole back of the figure is less fine, but

executed in the same way as the front, e.g. B. at the tedious and

intricate snake hem. Apparently one wanted to use this flattening to

create a support for an object connected to the rod. This speaks

clearly for the third possibility cited by Studniczka, that Athena was

holding onto her opponent's crest, as is often the case in vase

paintings [7]. The rod then means the high tube, which regularly

carries the metal crest with the bush in Attic helmets. Athena grasps

the tube, the crest resting on her fist. In her right hand the lance is

of course to be thought of: with a mighty stride she pierces the one in

front of her collapsed giant, grabs him tightly by the helmet and

plunges the lance into his chest. For the time being, the giant placed

in front of Athena may serve to complete the group, even if its

affiliation with Athena can only be proven later.

Although the

movement of Athena is thus clear, as a glance at Plate 3 shows, large

gaps remain and it should not come as a surprise that some pieces that

probably belonged to it could not be adapted. They are the following:

1.

From the back of the lower body. The flat surface shows three lines of

folds of similar work to those visible in fig. inventory no. 4199.

Height 27 cm, width 25 cm, thickness 15 cm.

2. From the right thigh:

a)

A piece just below the gluteus, with a fold line similar to those on

the lower leg. The obtained surface measures 17:6 cm, thickness 25 cm.

(p.66)

b) A little above the knee, with a similar crease. Height 12 cm, Width 19 cm.

3. Three pieces from the Aegis:

a)

The piece illustrated by Studniczka under No. 3, which, as he states on

p. 189, comes from the forearm, near the left hand; 13cm long.

b) A piece of the edge of the part hanging down at the back, 26 cm high, 10 cm wide (mentioned by Studniczka loc. a. 0.).

c) A piece of snake fringe, 12 cm long, with a snake head of particularly delicate and lively modelling.

Perhaps

the small remnant of a right hand, which held a weapon embedded in a

drill hole about 2.5 cm wide, can also be counted as part of Athena.

Only the beginnings of the index and middle fingers have survived,

which seem to match the masses on Athena's left hand.

The

colored decoration that she once wore is still missing from the picture

of Athena just obtained. Fortunately, enough traces of painting and

metal ornaments have been preserved to show how magnificently and

cheerfully the artist decorated the goddess.

Fig.3: fragment of border design.

The

scheme of that border is shown in fig.3. The (p.67) dark streaks show

the green, presumably resulting from oxidation of blue copper paint;

the filling of the rectangles has disappeared except for traces of red,

the spikes with blue dots at the top have almost completely

disappeared. The pattern of the meander can also no longer be traced in

detail; In any case, it was very artificial, as in the figure

reproduced in color in the antique monuments I plate 39 (Collignon, Histoire de La sculpture grecque I plate 1) (Acropolis Museum No. 682). I didn't notice any scatter patterns like those on this and other figures.

The

color of Athena's weapons is more closely related. The aegis, which,

thrown on the left arm, runs diagonally across the chest in a rather

narrow stripe, while at the back it once hung down to the knee, is

painted with scales inside and out, in such a way that rows of red and

blue alternate with colorless ones. A snake's body grows out between

each two semicircular sections of the edge, which bends back towards

the edge in the shape of an S, so that the neck and head lie on the

body of the neighboring snake. A wide blue stripe accompanies this

curved border and also marks the backs of the snakes, whose finely

modeled heads are animated with red lines and dots.

Remnants of

the blue paint on the helmet were still present when it was found [8].

In any case, it did not have a bronze coating, as can be seen from the

drill holes in the report of the Bullettino del'Instituto

1864, p. 85, which goes back to communications from Pervanoglu and

Decharme and has since been adopted more often [9]. It has not been

taken into account that the entire surface of the helmet is worked just

as smoothly (p.68) as that of the visible parts of the figure and that

the "Stephane" running around the helmet shows traces of bronze

decorations placed on the marble, wol gilded rosettes, namely 18

boreholes, several of which are surrounded by a slightly indented

circular area of 2.5 cm in diameter.

The two remains of

verdigris, which stick to the helmet in front and behind just above the

"stephane", are not the remains of a bronze coating, but are the result

of rust dripping off the bronze helmet crest. This was inserted into

the large square hole on the swivel; the bush hung very low: two

boreholes in the middle of the forehead, 20 cm below the rim of the

helmet, served to fasten it. Painting and gilding were certainly used

extensively on the crest and bush.

As on the helmet, the traces

of paint on the head have also disappeared, since the piece was set up

outdoors for a long time. Apparently it was painted in the usual way on

his lips, eyes and hair. The remains of the torso prove the hair: on

each breast four long, wavy locks of red color spread out, on the left

on the colorful background of the aegis, on the right on the white of

the robe. A broad red tuft falls on the nape of the neck.

Traces

of the jewelry usual on female figures of this time are not missing.

The earlobe disappears under a disc on which the circular ear ornament

was once attached in two holes drilled diagonally from the center into

the marble. Above the neckline of the Aegis, which is not shown

plastically but only in colour, there is a drilled hole on the left and

right of the shoulder curls, apparently intended for the attachment of

a necklace.

So magnificently dressed the goddess strides along:

in a bright robe resplendent with colored braids, in the colorful

aegis, towered over by the mighty crest radiant with gold and colors,

she herself radiates with healing, glad of the fight that is her

element.

(p.69) There is still a need to describe some of the

technical devices that seem to have been used to set up the figure in

the gable.

At the lower depression of the wide central fold of

the robe (fig.1 at a) there is a shallow square indentation of 10 x 7.5

cm, which must originate from a deep hole drilled from below through

the plinth into the figure. Mounted right in the middle of the figure,

it apparently served to anchor it in the gable floor. On the same

fragment, the right half of the central fold has been roughly worked

off with a pointed iron, up to a height of 40 cm, and on the left edge

of the break a similar work is aimed at 25 cm far up. One would like to

assume that both were made to push the opponent who has fallen at

Athena's feet close to her, but precisely these places are not touched

by the giant now positioned in front of her, whose affiliation can only

be proven later. So I can't give a definite explanation for this, any

more than for a round hole between 7 and 9 cm wide, which was driven

through the robe just above the plinth next to the right foot (cf.

fig.1 and 2 at b). It doesn't go through in a straight line because

you've worked in from the front and back at a slant downwards. Only

doubtfully do I express the assumption that it was made for the purpose

which it has now served again when the figure is set up on the base,

namely to pull the ropes through for winding up. One might want to

avoid letting these go under the base as they would be difficult to

remove later. The hole was of course covered by the giant in front of

it, which is also not visible in the current setup.

2. Athena's adversary

(cf. Plates 3 and 4). Studniczka had identified the fragments of the

giant to be grouped with Athena according to an external feature, the

red and blue color spots, which he noticed particularly numerous on a

group of fragments [p.70) of a naked man and as traces of the red and

blue scales Aegis paint washed away by the rain explained (p. 191). The

connection between these fragments and the movement of the figure

assumed by Studniczka has been ensured through the assembly; however,

that shrewd and captivating interpretation of the patches of color

proved to be deceptive when the figures were set up, and thus the only

external evidence that the figure belonged to Athena was lost. Since

the inner reasons for this can only be explained when considering the

whole composition, we will for the time being completely disregard the

relationship of the figure to Athena.

Plate 4: Rear view of the figure of a giant, grouped with Athena in Plate 3.

Now

the connection is established between this leg and the large piece of

the body (No. 9), 'which starts at the top with the lower edge of the

chest muscles and reaches about the middle of the abdomen'. The gap is

filled by a fragment showing the small of the back, most of the right

gluteus and just the beginning of the right thigh.

The gap

between the right lower leg and the right foot (No. 11) has also been

closed by a piece encompassing the heel and both ankles. The foot,

although stretched downwards, sticks to the ground only with the heel;

the sole is freely worked. A remnant of the plinth has been preserved

on the heel, which made it possible to find the position of the body on

the plinth. All that was needed was the small missing piece of the

right gluteus. on which the body rested and to lead the surface of the

plinth from there to the heel. The shape of the remains of the plinth

(p.71), like the lowering of the right foot, required the plinth to

slope from the center to the edge, as is also the case with these

figures.

The foot was attached in a very odd way, probably

having broken off during the work itself. The raw preparation of the

sole, which was only detached from the plinth with a few blows with a

chisel, shows that it was not executed on its own, but on the figure. A

piece of marble remained after the pickaxe, which Studniczka

misinterpreted as the remains of a tenon embedded in the base (p.191).

The leg is cut off where the instep attaches, roughly perpendicular to

the surface of the plinth, and numerous roughly horizontal, slightly

converging grooves are cut into the cut surface with a drill. Similar

ones are also found on the cut surface of the foot, but only toward its

outside. The rest is roughly picked and it turned out, when you put

your foot on it, that there was a wide gap between the heel and the

foot on its inside. Presumably the original intention of fixing the

foot with a thin layer of putty embedded in the grooves was later

abandoned and some marble was worked on at the foot in order to use

more putty. The purpose of a 2.5 cm deep drill hole in the middle of

the cut surface of the foot is not clear. There is nothing similar on

the leg.

For the production of the left leg, the part of the

lower leg known only to Studniczka (No. 12) was followed by its upper

continuation up to the knee, and not directly adapting it, but

certainly belonging to the foot after measurements and movement. A

piece from the middle of the thigh could most likely be added [10]. The

remains of the plinth, also preserved here on the heel, determined the

movement of the lower leg and thus that of the whole (p.72) leg, which,

slightly bent, only touched the ground with the heel.

The thigh

together with the knee was made up with the help of that remnant, and

the part of the body missing up to the large fragment of the upper body

(No. 9) was also filled in.

The production of the chest and

shoulders turned out to be unexpectedly fortunate. They could be

reassembled from a large number of fragments so that what little was

missing could certainly be added [11]. Only small gaps remained on the

back. The impression of the powerful, strongly twisted body is hardly

affected by these minor defects. The head and neck are unfortunately

completely lost, but one can still see from the fall of the long mane

of wavy strands of hair flowing down the back that the head was lowered

and slightly turned to the right (cf. the rear view on plate 4).

Most

gratifyingly, however, is that the magnificent right arm (No. 6), which

has always aroused admiration, fits the shoulder a little but perfectly

securely. He is not raised to defend himself, but sinks powerlessly,

similar to the way the head bows wearily instead of turning towards the

opponent. The missing hand was apparently holding a sword; it was

supported by a square piece of marble, the base of which survives a

stretch below the center of the chest. The stump of the lost left arm

is raised so high that the hand cannot have been on the ground.

p.73)

No doubt that the giant supported itself with the shield. A drill hole

on the left shoulder blade, already in the hair, in the middle of an

elevation of the marble that is now almost completely broken away, must

have served to fasten the shield rather than to attach the end of the

crest. The hole is cut by a second, thinner drill hole, which is made

at a slight angle from top to bottom in the surface of the back. It was

probably used to pour in the lead.

So there is hardly anything

left in doubt about the movement of the figure; Above all, what is

particularly striking about it is the violent rotation of the upper

body in the front view, completely secure, since the artist only

succeeded in this movement in the general plan. the addition of the

lower abdomen and left thigh had to forgo coming close to the original

and be content to close an unbearable gap as inconspicuously as

possible.

The position of her left hand was decisive for the

positioning of the giant in front of Athena, which was to be justified

later. He had to be positioned in such a way that the vertebrae reached

just under the helmet tube in that hand. Of course, with the loss of

Athena's left arm and the giant's head, only an approximation of

certainty could be attained, which, if I am not mistaken, is helped by

the group's favorable impression. The entire posture of Athena, the

strong bending of the upper body, the tilt of the head, the direction

of the gaze, everything is natural with the opponent in this position

close to her feet.

In any case, it is impossible to get the

giant's legs under the aegis in such a way that, as Studniczka assumed,

those spots of paint could have dripped off it.

Another

explanation for this is also suggested by the fact that, according to

Studniczka (p. 195), similar stains were also present on a right calf,

which can be assigned to the left corner figure of the gable.

(p.74)

Since this figure demonstrably only had the ascending geison above it,

the assumption is that it was the Sima, painted with a blue and red

pattern, which, with a suitable wind, caused the rain of colors to fall

on the parts that came closest to the outer edge who sent down figures.

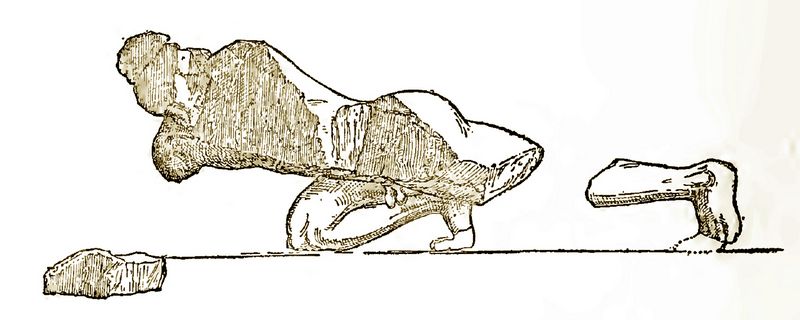

3. The right corner figure.

It is permissible to take this designation in advance for the figure

reproduced in fig.4, since the first glance shows that this figure is

composed for the right gable corner.

Fig.4: Drawing of figure of a giant in the right corner of the pediment..

Little

has been added to the large fragments compiled by Studniczka under No.

5, but a renewed examination of those fragments has taught us that the

movement of the figure is to be understood differently than Studniczka

had assumed at the time, and some new fragments have suited this

picture admirably inserted. Just enough of the right thigh is preserved

to show that the legs are spread too far apart to belong, as Studniczka

thought, to a striding figure (p. 193; cf. Fig.5 b there). Rather, the

figure has fallen to the right knee and stretches the left leg

backwards [12] The direction of the limb that was added confirmed this

assumption and parts of the legs could be partly (p.75) adjusted,

partly without hesitation to complete the figure used in this sense.

Footnotes:

1. Cf. Arch. Zeitung XXII, 1864, p. 233, Bulletino del'innstituto 1864

p. 85. Several pieces found on the north wall, east of the Erechtheion are mentioned in Ath.Mitt. 1887 p.145.

2. Cf. Ath.Mitt. 1886 p. 185 ff.

3. See Ath.Mitt. 1887 p. 367. 1888 p.107.

4. Cf. Ath.Mitt. 1888 p. 225.

5.

Cf. the illustrations in Overbeck, History of Greek Sculpture I p.194, or in Collignon, Histoire de la sculpture grecque I p.376.

6. B. Sauer had already gotten that far.

7. Cf. the a. a. 0. p. 190 note 1.

8. Cf. Postolakkas, Arch. Zeitung XXII, 1864, p. 233 *. Wolters, as he tells me, was able to detect a small trace of the blue color about ten years ago.

9. Milchhöfer, Athens Museums p. 54. Philios, 'Ephemeris arche " 1883 p. 94. Studniczka loc. a. 0. p. 189.

10. The same is extended almost to the knee by a 25 cm long,

18 cm thick fragment that Th. Wiegand subsequently discovered among the

fragments piled up between the two museums.

11. A small fragment from the right breast has received a

special feature which is indicative of the care taken in the execution:

a drilled hole at the level of the right pectoral muscle, apparently

intended to accommodate the nipple, which is made of a different

material. One finds something similar on marble individual works of

earlier and later times, e.g. For example, the archaic youth torso from

the Acropolis mentioned by Kalkraann in the Institute's yearbook 1892

p. 132 note 11 has nipples of blue marble. A Bohrlorh on the right

breast of Zeus Ammon from Pergamon must have served the same purpose ( Calalogue des sculptures du Musee Imp. Ottoman No. 68). Nothing similar seems to occur in decorative works.

12. This had already been joined by B. Sauer.

[Continue to part 2]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|