|

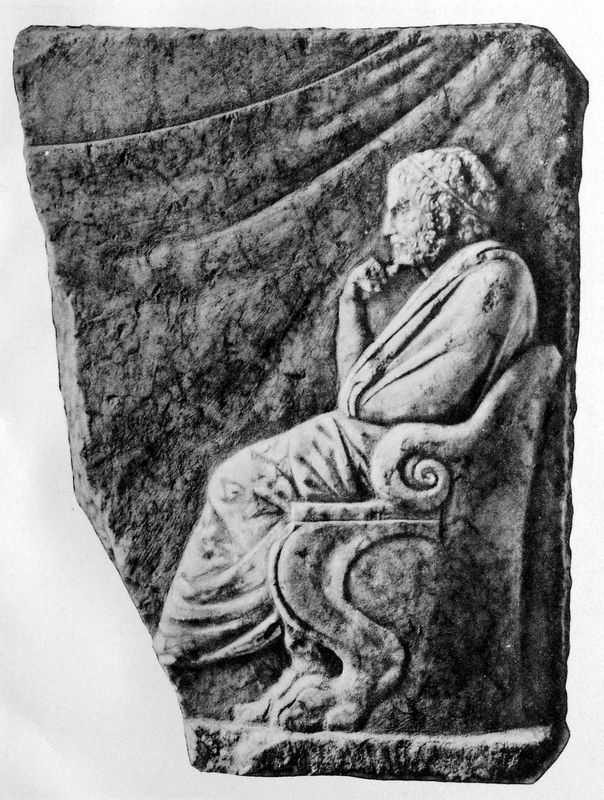

Relief Image of a Poet

[Ath.Mitt. XXVI 1901 pp.126-142]

The

relief fragment depicted on Plate VI was found on January 20, 1899

during the excavations of the German Institute on the western slope of

the Acropolis of Athens in a layer of ancient rubble. The circumstances

of the find do not allow any conclusions to be drawn about its origin.

It is a slab of Pentelic marble broken on the left, 0.21 m high, 0.16 m

wide at the top and 0.11 m at the bottom, 0.025 m thick, over which the

relief rises up to 0.012 m, the base slab 0.015 m. The bottom surface

is smooth, the other sides are left rough, only the front edges are

slightly smoothed. There is a pin hole at the top right, surrounded by

an approx. 0.06 m wide attachment. The top right corner is beveled. The

surface of the relief is overall well preserved, only small pieces have

broken off on the back of the figure's head, next to and above the eye

[1], on the beard, on the hand and on the coat on the shoulder. The

right foot is lost with most of the relief.

Plate 6: Relief of poet seated in chair.

The coat is

pulled tightly around the body, the lines of which stand out clearly.

The end of the cloak is thrown over the lap from behind and hangs down

in front, where it appears again between the leg and the chair over the

left foot. The left arm is completely hidden in the cloak. The right

leg is forward, the left one is put back and disappears behind the foot

of the chair. From the clothing of the feet one can only see the wide

piece of leather of the sandal on the left foot, which protects the

foot on the instep, on the right the end of the strap rising from the

heel, which is bent back, is still preserved. The seat is a stone

armchair with a half-high backrest and low, short armrests. Its

thickened edge ends in a volute above the seat plate. The seat is

supported by a lion's foot, modeled in very flat relief. These parts of

the relief are also carefully worked in a concise and definite form,

but without delicate detailed work. A striving for natural truth is

unmistakable in the treatment of garments. The deeply incised folds,

which are narrow and straight at the top, wider and with a sharp edge

at the bottom, successfully bring out the characteristic features of

the body shapes and the fabric of the garment. The tight drawing of the

folds where the cloak is wedged between the chair and the body, at the

crook of the knee and under the left arm, as well as from the shoulder

down to the left arm, is particularly significant.

Due to its

shallow depth of carving, the piece is to be counted among the

bas-reliefs. It is remarkable how the right, rear leg is worked at the

same height as the front one and only gradually disappears behind the

left knee, decreasing in relief. It corresponds to the law established

in the nature of the bas-relief that all parts of the relief remain as

close as possible to the surface of the stone when it is worked into

the stone. If parts of the representation that are to be thought of in

(p.128) different levels overlap, the level that is to be thought of as

deeper is led backwards at an angle, so that a slight difference in

height is noticeable at the overlap. [1]

The

position of the figure, which has been pushed into profile in such a

flat relief, is essential for the assessment. In the bas-relief, the

full profile position, which appears so frequently in archaic art, is

very rare in the times of the flourishing of art. Even if the profile

line of the faces rests directly on the ground, e.g. B. in the large

Eleusinian relief (Friederichs-Wolters 1182; ?????????, ?????? 126),

the bodies appear in a three-quarter view, so that the turned-away half

of the body also appears. A bas-relief with full profile position from

the IV century is the Bryaxis base in the Athenian National Museum (N°

1733, BCH 1S92 taf. 3, ??????'?? ???????. 1893 taf. 6); perhaps the

depiction of the rider made it necessary here. Only in the second half

of the 4th century does the frieze of the Lysicrates monument offer a

number of examples of pure profile positioning. The artist of this

relief not only placed a seated figure perfectly in profile, but also

went beyond the natural limits of the bas-relief by allowing the left

arm to reach the ground and thereby attempting to gain the illusion of

greater depth. [2]. In this way the impression of full physicality,

which otherwise only high relief can give, is achieved, and the eye of

the beholder is deceived at first sight. But soon, when the gaze is

drawn to the plastic elevation, one notices that the shortening of the

left forearm has failed, even if it is less noticeable due to the

covering, and (p.129) feels the squeezed position of the left leg

behind the foot of the armchair as unsightly.

According to the overall impression of the work,

the relief must be placed as close as possible to the best times of

Attic art; but the realism of the treatment of the drapery and the

peculiarities of the technique of relief discussed make it impossible

to think of it having arisen earlier than in the last decades of the

fourth century BC.

The fact that the background of the relief is

plastic is no longer striking for this time, even for earlier ones

there is sufficient evidence. The Ivybele and Attis relief in Venice

[3], which is closely related to the Praxitelian muse base of Mantinea

and to the tripod base in Athens, which Benndorf traced back to

Praxiteles [4], should be cited as an example that can be fixed more

precisely in terms of time. At the bottom of this relief the door of

the sanctuary in which the deities are located is indicated in plastic

form. In the case of nymph reliefs and some hero reliefs [5], landscape

staffage can be found as early as the 5th century BC.

The shape of the sandals described above with the backwards bending heel strap does not seem to be common [6]. It is only known

to me from the representations of the Homeric (p.130) cups [7], where

such “spur-like hooks” (cf. Robert, p. 62) are noticeably large

attached to the men's footwear. It can be assumed that at the end of

the IV century this fashion began, the further developed form of which

we meet on the Homeric cups at the end of the III century.

Since

only the bottom surface of the relief is smoothed, it must have been

mounted freely on a relief support. It may have broken at the bottom

just where it was mortised into the girder. The top finish is unclear;

the smoothed area around the pin hole seems to indicate a corner

acroter. As a votive offering, the relief will have stood near the

Acropolis, if the addition suggested below is correct, in an area

sacred to Dionysus.

The addition is to be based on the attitude

of the sitter. He is not lost in thought, but he is contemplatively

looking at an object or a person who was at eye level across from him.

A

seated figure in this position of contemplation, which is very common

on tomb reliefs, is found once on a very ruined Asklepios relief in

Athens [8], but the proportions and the overall layout of our relief

make it appear that it belongs to the group excluded from the Asklepios

reliefs. On the other hand, the furnishing with a curtain, which moves

into the interior of a room, and a large armchair in connection with

the posture of the seated man suggests that this is a model for (p.131)

a type that was not present in later times rarely used to represent

poets. In a special composition, a poet seated opposite a mask, a type

closely related to our relief recurs several times. I am aware of the

following examples:

1. Berlin, description of

the sculptures N° 844. Sarcophagus with representation of the muses

from the Via Appia [9]. "The lid shows scenes from literary life on

both sides of the inscription." «Following the inscribed panel on the

right is a group in which first a tragic mask corresponds to the comic

one in the last scene to the left of the inscription; below her lies a

cloth over a rock. A bearded man, seated on a high-backed chair, is

looking at the mask, facing left, holding a scroll in his left hand and

raising his right hand to his face as if in thought. A diptych appears

to be attached to the rock beneath the mask. (Replaces the right arm

and the first forearm, both except for the hands)». The feet are bare,

as in the two following reliefs.

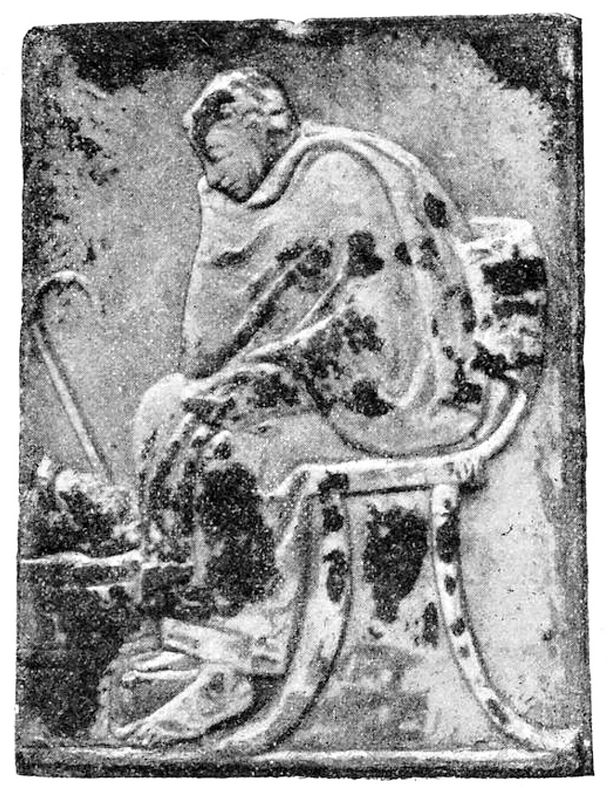

Fig.1: Relief from Villa Albani with two bearded man and large mask.

2.

Relief in Villa Albani [10], shown in fig.1. Size 0.33 x 0.21 m, below

the marble predominates as a base plate; the thickness is not visible.

The marble is coarse-grained and heavily glimmered, perhaps Thasic. The

additions—the head of the left figure, on the right part of the 1st arm

and r. Fusses—can be seen in the illustration, as can the current

wooden frame of the panel. The wide furrows of the interior design

point to the III century BC. A bearded man, whose head is noticeably

better carved than the rest of the relief, is seated on a boulder to

the left. He is dressed only in a cloak that hides both arms [11] and

looks at a large mask that stands (p.132) on a covered pedestal in

front of him. Behind the mask a second man, in all respects very

similar to the first, to the right, raising a scroll with his left.

Fig.2: Relief of seated man from Pompeii.

4.

Berlin, Gemmen 7679: «Bald-headed, fully clothed man seated to the

right and musingly contemplating a tragic mask standing in front of

him». 7680 «the same Upper body naked». The mask stands on an

altar-like pedestal and, like the first two depictions, is larger than

life in relation to the seated figure [15].

In these specimens, the poet's pose corresponds

fairly closely to our relief. The frequency of the composition of poet

and mask may be illustrated by a few more examples in which the poet

occupies a somewhat different position.

The monuments that Zoega

[op cit., Note 2) — the well-known Hellenistic relief image from the

Lateran and two Herculanian murals — are to be consulted later. Welcker

(ibid. note c) has collected further examples. Of these, "a small piece

of marble, a poet seated in front of a mask, has moved into a garden

wall of the Villa Poniatowsky" no longer exists; it is missing in

Matz-v. duhn A fragment from Palazzo Barberini («One is reading from a

scroll ; his listener leans on a column and one does not notice a

mask») will, if the additions are taken into account, be identical to

the tomb relief of Matz-V. Duhn 3729 (reprinted from Arch. Zeitung

1872, 138 Taf. 53, 2). I was not able to compare the tombstone

(Fabretti inscr. p. 704) and the gems mentioned by Welder. Finally, the

relief from Villa Altieri that Welcker mentions has recently been

published by Robert in Sarkophagreliefs II 52 N° 141 p.154. Pozzo's more

complete drawing (N° 141' on Plate 52) of the later (p.135) fragmented

piece gives a group of four 'letterati' including at the right end of

the row a bearded man raising his right hand in a gesture, with a

scroll in the Seated to the left in front of a large mask standing on a

round pillar [16].

A "letterati" on a

sarcophagus frieze in the Lateran (Robert loc. a. 0. N° 143) has the

same position. Benndorf and Schöne Lateran N° 12 b Plate 18,1 testify

to the mask in front of him. A curtain is stretched out behind him.

A

sarcophagus fragment in the British Museum - shows a bearded poet

seated to the right with a very similar arm position. A girl — probably

a muse — holds the mask out for him to look at.

Gems with such

representations are Furtwängler Gemmen I Taf. XXV 26. XXX 41, 45. LXI

60. LXII 9, Berlin Gemmen 4505, 4506. The poet reads on these; Berlin

gems 4524 show him gesticulating.

The examples show how popular

this combination of a poet with a mask was in later times. Among them,

the type of the pensive man, as shown in our Athenian fragment, is

represented several times. Since no new motifs were invented at that

time, but only old ones borrowed, one must conclude that this

composition was invented in good Greek times, and there is the greatest

probability that the Athenian relief can also be supplemented in a

corresponding way . It is then to be understood as a votive gift from a

scenic poet, and one may assume that such votive offerings were so

common in Athens in the IV century BC that they became typical of

poets' representations. In his discussion of Greek votive offerings (p.

54), Reisch also took this genre into account and cited the most

important examples.

In

his assessment he starts from the Hellenistic relief in the (p.136)

Lateran [18] and classifies this and thus the whole group among the

scenes from daily life, in which the consecrators see an image of

themselves in their usual occupation of the offering deity. In our

compilation, that relief and the similar relief fragment in Berlin that

Reisch uses have been deliberately omitted [19]. The Berlin fragment

(Sculptures 951) comes from Aquileia (fig.3): «a beardless young man, clothed

underneath, sits on a chair to the right, his right hand rests on his

chin, in his left he holds a bearded comical mask in front of him and

looks up. On his feet he wears delicately bound sandals».

Fig.3: Relief from Aquileia of a seated young man holding an actor's comic mask.

In

the Lateran relief, Petersen [20] sees a poet transported into an ideal

world, while Reisch attributed it to an actor. This latter

interpretation, which never seems to have been in doubt for the Berlin

relief, has the greater probability for the Roman relief as well.

Because the depiction is interpreted casually in such a way that the

actor has just used the mask he is holding in his hand or intends to

use it in the near future. The same positioning motif is already used

on vase pictures for actors, as with several actors of the Pronomos

vase [21] and on a vase in Munich [22], whose picture O. Jahn indicated

that Dionysus surrounded by his demonic companions as the founder of

the Tragedy presents the tragic mask to a mortal — poet or actor. But

the Silenus on the right is clearly identified as a masked actor by the

shape of his mouth and shoes, as is the satyr on the left with a

rounded ridge on his forehead, like the mask held by Dionysus has two.

Accordingly, the youth with the Thyrsos is certainly an actor who

probably has to play the role of the god himself and receives the mask

from his hand [23]. The way in which the god raises the mask and looks

at it (p.138), about to hand it to the youth, fully corresponds to the

positional motif of the two reliefs.

If actors are rightly recognized in those

representations, then they are to be completely separated from our

group of votive reliefs, because with these musing men, who mostly

appear bearded and of advanced age, the thought of actors is quite

remote. In addition, the masks that appear on these reliefs are not

utilitarian masks, but must have a special meaning, since they are

considerably larger than life size, with only one exception, the relief

from Pompeii [24]. It is natural to recognize images of votive offerings

in them on votive reliefs, and this also explains the depiction —

portrait of the consecrator and next to him an image of his votive

offering that he offered an image of it together with the image of

himself is well known from monuments in Athens and is easily

understandable from the intention of the donor to draw the god's

attention expressly to his person [25.

In the IV century BC, to which the examples given

below belong, such a composition of images of the (p.139) consecrator

and his gift is quite common. For some, the composition is purely

external. In the composition of the poet and the mask, an inner

relationship unforcedly arose: the picture was given content in that

the poet appeared lost in contemplation of the mask. But it would be

absurd to see in this a scene from the sphere of daily life, a

representation of daily occupation. The dedication of masks is only

documented in literature by actors and choruses [26], but is factually

also conceivable for poets, and the depiction of a man immersed in deep

contemplation not only suits a poet, but is also in later times for the

poet become typical.

The question is still open as to how the

fragment should be supplemented with an image of a mask in detail.

According to the course of the folds in the background, the missing

piece must have been at least as wide as the surviving one; that gives

a total width of 0.32 m, maybe more. Even if one assumes that the mask

and pedestal are as large as possible, there is always far too much

free space between the mask and the figure. There are two ways to solve

this difficulty. Either one could think of the dedication not of a

single poet but of two and supplement the fragment according to the

analogy of the Albanian relief shown above, an assumption which is not

advisable, since the combination of two writers is probably to be

attributed to the sarcophagus makers, or — and this is more likely —

there is a somewhat altered form of these consecrations.

Among

the examples given above (p. 135), the sarcophagus fragment from the

British Museum stands out from the rest by the significant difference

that on it the mask is held out to the poet by a muse for inspection.

This motif leads over to a Herculanian painting, Pitture d' Ercolano IV

39 (p.140) (Helbig mural 1461), in which one may also recognize a poet

in the company of the muse. Here the elements of our composition, the

musing man with his chin on his hand and the mask, return, albeit as

components of a somewhat more elaborate composition [27]. Given the

dependence on older models, which one must also assume here, one may

venture the conclusion that the invention of this scene "the poet in

his room in the company of the muse devoted to his activity" in the IV

century BC and because of the Athenian relief on Attic soil to relocate

[28]. If one imagines a muse with a mask sitting on it opposite the

poet, a supplement results which formally corresponds to the size and

the demands of symmetry and which is completely satisfactory in terms

of content. Such a relief picture, intended as a further development of

those simple dedications that give the poet alone with the mask, at the

same time in its still simple form a preliminary stage of the richly

decorated pictures of Hellenistic and later times, also fits with the

chronological approach to the end of the fourth century BC, which was

obtained above on the basis of the relief technique.

Finally,

a few monuments are listed that may come from similar dedications by

poets. Characteristic of the Athenian relief is the delicate work with

which the portrait features are expressed despite the small dimensions.

Such things do not seem common; The following pieces have become known

to me so far, which for this reason may be related to our relief.

1)

A small remnant of a relief, head and upper body of a man sitting in

the National Museum of Athens N ° 1360, described by Duhn [29], who

particularly emphasizes the "portrait features". The relief-in its

circumstances only 1/3 greater than the discussed-shows a bearded man

in three-quarter view that appears in deep thoughts. His hair is

divided into width, somewhat wavy strands, the forehead is divided by a

few wrinkles, the eyelids are cut off, the swelling of the baking nose

and a fold on the nose setting stands out significantly. The robe has

deep, in parallel down folds. The folded hands that encompass the knee

have only four fingers each, since the fingers are too big. The work

probably points to the first half of the IV century BC. I am unable to

confirm that Duhn's statement that the look was directed towards the

lowering of the eyelids. The whole position is reminiscent of a well

-known gem image [30] a dramatic poet who practices a choir.

2. Fragment in the Galleria delle Statue, which Helbig leaders 1 200 describes and (Yearbook 1886, 77) considers to be Plato.

3.

The relief of a reading man, the so -called Sophocles, which O. Jahn

images Ehr Otiiken II 4 (see p. 57 note 385) depicted. The dimensions

of this figure are somewhat smaller than that of our relief, the work

seems almost finer. Unfortunately, the newer publication of Babeion Le

Cabinet des Antiquites A la Bibliotheque Nationale is missing; I was

not able to obtain a photograph.

4.

Relief fragment owned by Prince J. Primoli, the A · Chaumeix (Melanges

d’Archeology 1899 Plate 5 p.159) published. It is only preserved and

the head and right arm of a sitting of a bearded man. Chaumeix is

rightly attributing the relief to the V century BC, because if you can

compare such a fragmentary piece,

with works of great art, between this and the Berlin Anacreon

head, and the Kekule of Straclonitz, between the Olympic and Parthenon

sculptures, appear to reveal clear stylistic matches. Both have the

main hair (p.142), which, as far as the binding holds together, is only

very flat; The full beard in individual flakes, the strong eyelids and

the still clumsy way, as the mustache stands out, return to both. The

attitude is very similar to that of the poet on the Athenian relief.

The

fact that the publisher concluded on a philosopher is not unexpecrted,

but

its reasons, which are only based on this attitude and the gear, are by

no means proof. It is quite possible that this fragment also comes from

a consecration of a Scenic poet. The fact that it is kept in more than

twice as large as the Athenian fragment can be put on the account of

the older times. You also have to recognize a poet on the next side of

a sarcophagus in the Museum in Naples, where Arndt [32] sees a

philosopher. “In front of a parapetasma, a philosopher, docolving, just

wearing the rimming, sits a knot in his hand; A role capsule next to

him; A four -foot animal in front of him. The trains are like that of

the diogen, so the animal should probably be a dog ». The work shows

the deep, broad furrows of the interior of the III century BC, similar

to the Albanian relief shown above (p.132). In the same time,

the raw combination of the curtain shows as a designation of a closed

room with the rock on which the poet sits. This is completely in line

with the position and crowd arrangement the denser mentioned in front

of the mask on the Pozzo sarcophagus - drawing, which is the last in

the row on the right [33]; Only on the relief the gesture of the two

fingers outstretched is clear. Apparently a poet can also be recognized

here, and he is characterized by the shepherd's staff and the sheep

next to him - it is certainly not a dog - as a Bukolian poet.

Athens, June 1901. Emil Krüger.

Footnotes:

(footnotes)

1

Löwy The representation of nature in older Greek art p. 21 emphasizes

this phenomenon on the Parthenon frieze: «Even if there is a slight

difference in the plan where parts to be thought of one behind the

other meet in the relief, then in the further course the Faces forward

again. . . . »

2 Beginnings of perspective foreshortening, but

in higher relief, states A. Brückner on the Eleusinian rider relief

(Athen. Mitt. 1889 Taf. 12 p. 403), which he places at the end of the

5th century BC.

(footnotes)

3 Collignon bas-reliefs grecs votifs. Monuments grecs N'-' 10. 1881 plate II p. 11.

4 Austria Jahreshefte 1899 Taf. 5 - 7 p. 255. The figure of Attis

corresponds completely to that of the Scythian - only with the right

and left being swapped around again; the adoring woman's robe is

reminiscent of one Nike on the tripod base (ibid. 0. Plate 6). The girl

is a type of the position and hand position found on Attic funerary

monuments (Conze Att. funerary reliefs N° 878 and 879). The relief

is therefore certainly Attic and under the direct influence of works from the circle of Praxiteles.

5 Hero relief from Museo Torlonia Fr.-W. 1073, published in Roschers

Lexikon I Col. 2559; Fragments of similar depiction in Athens, National

Museum N°I35i, assembled from Sybel N° 4300, 4660, 4804 and two other

pieces; see also National Museum N° 135S

6 The strap rising from

the slab, which extends beyond the upper end of the sandal, is not

infrequently found lying flat on statues, e.g. B. in the so-called

Aristotle in the Palazzo Spada (Helbig Führer2 998), in the seated

Hermes from the Herculanian villa (Comparetti La Villa Ercolanese Taf.

13,2) and - at least according to the drawing by Clarac - also in one

of the four fencers in the museum of Naples (Clarac 865, 2203; Count

Rom. Mitt. 1897, 30 plate II) ; also two bronze feet of good work among

the new finds from Antikythera have this strap.

(footnotes)

7 Robert Homerische Becher,

50. Berliner Winckelmannspr. pp. 26 D, 30 V 51 L. Winter yearbook 1898,

83 plate 5. For dating and origin see Dragendorff Bonner yearbooks 96,

29.

8 Athens, National - Museum N° 1365— Arch. Zeitung 1877, 15°

N" 26, now completed by the left end: a woman stands to the right,

leaning on a pillar with her left arm.

[footnotes)

9 Also illustrated in Arch. Zeitung 1843 plate 6.

10 Zoega, Bassirilievi übers, von Welcker I 205 II plate 24. Zoega

erroneously calls the pedestal of the mask a cißptis. It is a wooden

frame with feet shaped like lion claws. I owe the photograph and the

information about supplements, dimensions and material to Prof.

Petersen, who was also willing to support me with his advice in other

respects.

11 The part of the cloak that reaches over to the pedestal

in front of the right leg is striking; it was probably caused by the

carelessness of the stonemason, who made a change to the model—e.g. put

the back feet of both figures back while they were presented in the

model—and was not consistent performed. It is strange that the same

error recurs in the falsified relief of Demosthenes Epibomios (A.

Michaelis Jahrbuch des Inst. 1888, 237), which corresponds to this

figure in the position of the feet and the position of the right arm.

(footnotes)

12 The accompanying figure is based on a photograph that Prof. de Petra

had made, despite the difficulties involved in setting it up, for which

I owe him a special thank you.

13 I am indebted to Mr.

Perdrizet for pointing out the image of a poet with a scrinium next to

him in Virgil's Codex Romanus (Melanges d'archeol. 1884 320 N° 2),

according to which this case also seems to have been intended for

scrolls. See also Arndt single sale 530, discussed below p. 142.

footnotes)

14 This relief is one of the very flat reliefs that are considered to be

Hellenistic, such as the Naples Museum has in large numbers. The

closest comparison among these is the relief of a Silenus embedded in

the same wall, sitting on a fur-covered altar and looking at himself in

the mirror (Inventar. N1' 6697). But the poet's relief is far from the

most delicate and delicate execution like this, and like all the better

of these bas-reliefs, it stands quite alone with its unclear and

blurred drawing. This phenomenon cannot be explained solely by the fact

that the system is volatile from the outset, e.g. B. the seat board of

the chair is drawn crookedly, the fluting and the central band of the

roll cap are scratched irregularly, but it is obviously an unfinished

piece. The part between the legs of the chair already leads to this,

where only the contour is cut, but the ground is not excavated. The

incompleteness is quite clear at various points where lines are

supposed to intersect, but this intersect has not been carried out and

small connecting pieces have remained: for example at the front corner

of the upper backrest of the chair, at the squat, at the upper edge of

the roller capsule; also at the end of the coat, which hangs down in

front of the back of the chair, there is no tassel to be seen, as is

the case e.g. B.mus. Borbon. XIII, Taf. 21, but such a bridge.

Furthermore, the left foot is not set off at all against the cloak, the

face, llaar and mask are only laid out in the roughest outlines and

still require individual execution. This also explains how it is

impossible to tell whether the left hand holding the scroll is under

the cloak or exposed. Presumably, the piece had not yet left the

sculptor's workshop at the time of Pompeii's burial, of which it bears

clear traces, and the origin of the work must be dated to before 79 AD.

15 Cf. also the similar depiction Gemmen 7406 (illustrated erroneously

7407) "Silenus with a long crosier sits in front of a mask lying on an

altar"-

{footnotes)

16 A second from this

literary group turns back to a mask standing behind him, which he

grasps with his right hand. This peculiar position appears only here.

17 Ancient Marbles X Plate 34, now reproduced from a photograph by Strzygowski Orient oder Rom p. 51.

(footnotes)

18 Schrieber Hellenistic relief 'pictures plate 84, Benndorf-Schoene Lateran N° 245, Helbig guide 2 684.

19 Similar gems are Berlin gems 4520 — 4522, 7681.

(footnotes)

20. From ancient Rome [2] p. 134.

21 mon. deli Inst III 3i, Wieseler Theatergebäude Taf. Prott Schedae

in honorem Useneri S-47ff. Incidentally, it should be noted that the

poet is characterized here only by the role. The lyre behind him

belongs to the next choreographer, who is the only one missing the mask

and who would otherwise be without an attribute among all those

portrayed. This confirms Prott's assumption that Charinos is the

twelfth choreut. Apparently each half-choir appeared with a satyr

playing the lyre. Because Charinos corresponds to the seated poet

Demetrios in the arrangement of the 4 figures in the lower middle

group, the artist has depicted him in the same clothes as the latter,

but without a costume.

22 O. Jahn description of the vaset collection ?? 848, Arch. Zeitung 1855, 147 plate 83.

23 The result is a picture: Dionysos among the actors, very analogous to

the well-known relief from the Piraeus, now in Athens, Nat.-Museum

N°i5oo (Robert Athens. Mitt. 1882 Taf. 14 p. 389, Maass yearbook 1896,

104).

footnotes)

24 Due to the time of its creation before 79 AD, this relief should hardly

be used as a votive relief, but decoratively and no longer reproduces

the original type of this relief unchanged.

25 Whether among the

examples of this usage the relief of a warrior next to a tropaeum

(upper half of a small marble base, now in Acropolis Magazine N° 3173,

Schöne Griech. Reliefs N° 97) in the style of the Orpheus relief may be

cited doubtful. Safe examples are:

a. Fragment of a relief in the

Acropolis - Magazin N° 2995, from the Wiener Vorlegebl. VIII, 10,4,

Friederichs-Wolters 1196. A bearded man in front view, behind him a

tripod; choreographer or poet.

b. Relief in Athens, National Museum

N° 1490, Sybel 3983, from Arch. Zeitung 1867 plate 226, 2. A man en

face, to his right a satyr places a tripod on a pedestal.

c. The

base of the Bryaxis, Athens, National - Museum N° 1733, abb. BCH 1892

plate 3. A horseman riding towards a tripod. i.e. The votive relief to

Asklepios, the A. Koerte Athens. Mitt. 1893, 235 plate 11 published.

The healed person (hardly the doctor) brings an image of his sick leg

himself.

footnote

26. Reisch op cit. 8.144

ootnotes)

27 The painting Pitture d’ Ercolano IV 40 (Helbig 1457) also brings the

thoughtful man and a mask held by a young man. Unfortunately it is entirely destroyed.

28 That always remained a popular topic; See

sarcophagus in the Louvre Clarac II 205, 307 Text II, 1 p. 247, Matz-V.

Duhn 2610, 2616, sarcophagus from Lykien in Athens, National Museum N °

1189 Athens. Mitt. 1877 Plate 10 p.134, the Monnus mosaic in Trier

Antique Monuments I 47-49, The Virgin Mosaic in Algier Monuments Piotly

20 (Arch. Anz. 1898, 114); In addition, the sarcophagus images that

show the dead in the circle of the muses, O. Bie Die Musen p. 59.

(footnotes)

29 Arch. Zeitung 1877, 163 N ° 73.

30 Wieseler Theater Gehen XII 45, now better at Furtwängler Gemmen XXX 44

31 A philosopher in this attitude z. B. on the philosopher mosaic by Torre Annunziata Arch. Anzeiger 1898, 121.

32 single sales 530, text Series II p. 47

33 above p. 135, Robert Sarkophageliefs II 14T,

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|