|

Precinct of a Healing God on the West Slope of the Acropolis (Ath. Mitt. XVIII 1893, pp.231-256).

During

the excavations undertaken by the Athenian Institute, which led to the

discovery of the city fountain of Athens, the Enneakrunos, the precinct

of a healing god unexpectedly came to light on the western slope of the

Acropolis, of which Dörpfeld gives the following description.

‘On

the eastern side of the old road leading to the Acropolis, between the

Pnyx, Areopagus and Acropolis, the entrance and the western boundary

wall of a district came to light, which the finds made in it turned out

to be the sanctuary of a healing god’.

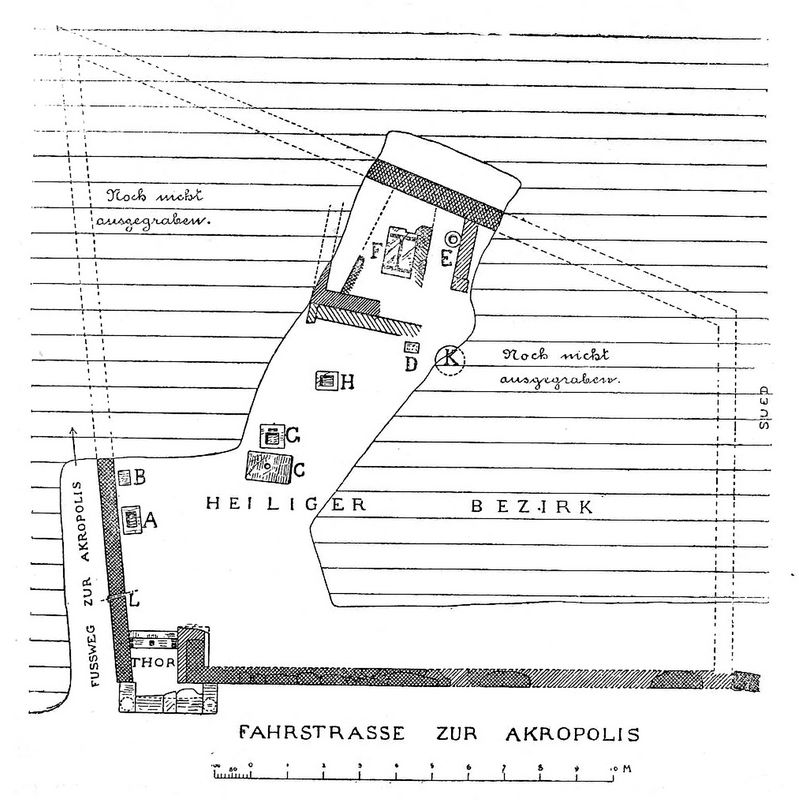

' The dimensions of a

ditch drawn across the district are determined to such an extent that

its circumference can be given at least as a guess in the drawing below

(fig.1). Its exact form can only be determined when the excavations

are planned to continue'.

' In plan the district seems to have

formed an irregular square, of about 17m mean length and about 13m

mean width. The entrance is not, as is usually the case, in the middle

of the side of the square adjoining the road, but at the north-west

corner, evidently because at this point a second path leading directly

to the Acropolis branched off from the larger road. In the case of a

sanctuary situated on two crossing streets, the arrangement of the

entrance at the crossing point was the most appropriate'.

Fig.1: Plan of the Sanctuary, as partially exposed in 1893.

'What

was uncovered of the enclosing wall and how much (p.232) of it is still

preserved can be seen from the plan. The destroyed parts are light,

those that are preserved are shaded darker; the pieces not yet

excavated are only in dotted lines. The material of the wall is the blue hard

limestone that makes up the Acropolis rock and the neighboring hills.

The individual stones are cut polygonally and carefully joined

together. In accordance with the different meaning of the two paths,

the wall on the road is made of larger stones (up to 1.40 m long), while

the one on the footpath is made of much smaller stones.

' The

entrance gate changed its shape in antiquity. (p.233) Originally it

consisted of a double door with a simple vestibule, which probably had

no architectural decorations. ln Roman times, when the street floor had

been significantly raised, a higher read special porch is made of

bluish marble and is probable equipped with two pilasters or columns.

The width of the old gate is 1.31m, which corresponds exactly to four

ancient Greek feet.

'Inside the district, important remains of

the original furnishings have been found: several foundations for

votive offerings of various forms, several beliefs which appear to have

formed votive offerings for a healing god and one of which contains the

name of Asklepios, the foundations of a chapel with the lower part of a

sacrificial table and finally the large estuary stone of a well.

'Of

the foundations, which by their design have borne votive offerings,

most (?, B, C, D and E) are still in place and only two (G and H) are

perhaps somewhat removed from their original location. They all carried

reliefs, round columns or steles, as can be seen from the various inlet

holes and traces of attachment.'

The reliefs themselves that

were found were no longer in their original place. Also the large

relief with the man carrying a large leg, which appeared standing

upright between the gate and the base A close to the enclosing wall,

probably no longer took its original place because of the lack of a

special foundation. At the same time, the supposition expressed in

Athens that the reliefs had been carried here from the large

Asklepieion on the south side of the Acropolis is completely

inadmissible. Since the reliefs have been found throughout the district

and at different heights, one would have to assume that they had been

brought here (p.234) in different centuries, precisely to a place where

there were foundations deep in the earth for similar votive offerings .'

'

Particularly valuable is the lower part of a marble table (F) found in

its old place, from which, apart from the base, the remains of two

table legs, each with lion's paws, and the plate connecting them are

preserved. The latter was decorated with two snakes on the north-facing

side, as can still be clearly seen from the small remains. The table

appears to have stood in a chapel; in fact, in its vicinity one sees

several walls, dating from different periods, which probably formed a

small temple. However, its shape will not be known until the entire

building has been uncovered.'

' Finally, the large estuary stone

of a well deserves to be mentioned, which came to light at K. It

doesn't seem to be in its old place anymore, but because of its size it

shouldn't have been moved far from its original place. The presence of

a well could be expected for the precinct of a healing god, because a

well or spring is always part of an asklepieion. The fact that there

was water in our district is also secured by a gully that was laid in

the northern enclosing wall (at L) when the district was built. It is

very likely that a water pipe can also be assigned to the district,

which branches off further south from the large Pisistratic water pipe

of the Enneakrunos and leads drinking water under the road to the area

of our sanctuary. Only further excavations will shed light on this, too.

'

It is currently not possible to determine exactly when the sacred

precinct was created. From the polygonal construction and the material

used, it is only certain that it comes from older Greek times. However,

since several buildings on the old road and (p.235) perhaps this road

itself owe their existence to the Pisistratid period, our sanctuary can

also be assigned with some probability to the sixth century BC.'

I will follow Dörpfeld's description of the sacred area above with a discussion of the individual finds.

1.

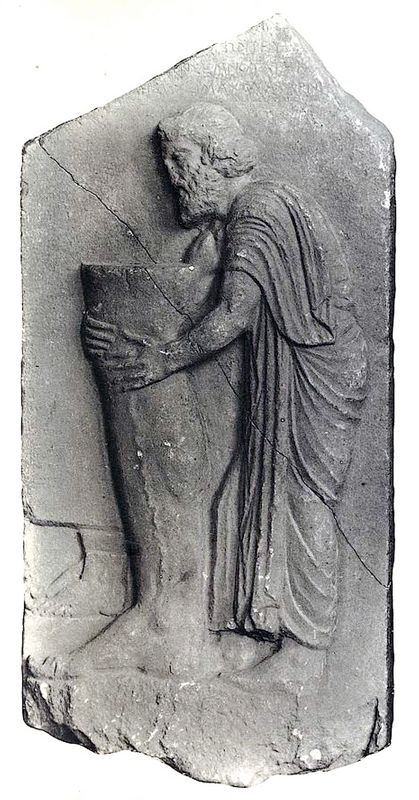

Votive relief (fig.2), height 0.73ra, width 0.35m. Pentelic marble. The

top part is missing, the plate is also broken diagonally, the fractured

surfaces close together well. The lower edge is left rough. it was

apparently embedded in a base of the kind shown at A-E, G and H on the

plan. The relief was found just to the left of the old entrance

(between this and L) leaning upright against the wall, with the

sculpted side towards the interior of the precinct.

Plate 11 Votive relief No.1 .

A

bearded man standing to the left, slightly bent, grasps with both hands

a colossal right leg, which is on the ground in front of him and

reaches to his chest. Both of his feet are on the ground with their

whole soles, the right one is slightly forward. His cloak is wrapped

around his body from his left shoulder under his right armpit and then

thrown back over his left shoulder, leaving his right shoulder and half

of his chest free. The head with a fairly long, pointed beard is in

good condition, only the nose is slightly chipped. The full head of

hair is tied up at the back in the manner that is particularly

characteristic of Dionysus; the same hairstyle can also be found on

some Asklepios heads (Ziehen, Athens. Mitth. XVII p. 243 ff.).

One

might be tempted to take the man for the god of salvation himself

because of this hairstyle, but the size of the leg in front of him

forbids that; it is impossible for the god to be represented smaller

than, say, a votive offering in his sanctuary. On the colossal leg a

strong vein stands out very conspicuously, extending from the man's

left hand to the ankle; no doubt it is intended to indicate the

suffering from which the patient was freed by the (p.236) god—he was

suffering from varicose veins. That the scene is intended in the

sanctuary itself,is indicated by the two feet, which are set up

in a niche on the left in front of the leg and are also to be

understood as votive offerings. The sanctuary of a healing deity on a

Boeotian crater of the local arch. Society (5840, illustrated Έφγιμερίς

άρχ. 1890 Taf. 7), marked; I am not aware of any corresponding

indication of the inn on Attic votive reliefs.

The depiction of

our relief has so far been completely alone among the votive offerings

to healing gods. Three classes can be distinguished among these votive

offerings.

The simplest form is the simple replica of the healed

limb, a form of thanksgiving to the deity that has survived to our day.

The inventories of all sanctuaries of healing gods list such links made

of gold or silver [1], stone-worked ones have been found at the most

diverse places of worship, and they are not lacking in our sanctuary

either (see nos. 6-8, 11, 12)

A second form is that the healed

person presents himself and his family showing their thanks to the god

through sacrifice and worship. This is where the overwhelming majority

of the reliefs found in the large Asklepieion on the southern slope of

the Acropolis belong.

Finally, the healing is sometimes represented by the god himself (cf. Ziehen, Ath.Mitt. XVII p. 230 ff.) [2]

On

our relief we now find a new form, as it were a fusion of the first and

second types of votive offerings. The healed limb is shown, but at the

same time (p.237) its offering by the dedicant; the god, of course, who

forms the center of most of the reliefs, is omitted here.

It

remains uncertain whether the depicted dedicant is the healed person or

the doctor. For the latter assumption one could cite the appearance of

the man, which approximated the type of the god. It is quite possible

that a doctor once made a votive offering to his divine master for a

particularly successful cure. In one of the reliefs from the

Asklepieion (No. 41 Dulin), Girard [3] most likely has the votive gift

of a doctor -Collegium suspected. and that the physicians sacrificed

twice a year to Asklepios and Hygieia ύττέρ τε αυτών καί των σωμάτων ών

έκαστοι ιάσαντο is handed down in writing (C.l.A. II 352b).

The

work of the relief is manual but fresh, as is the case with most votive

reliefs from the Asklepieion. The fact that we are encountering an

otherwise unknown type here makes it advisable to start the relief

relatively early, before the types for these votive offerings were

completely rigid, i.e. in the first half of the fourth century. The

written character of the inscription above the man's head also fits in

with this, which is unfortunately too severely mutilated to allow a

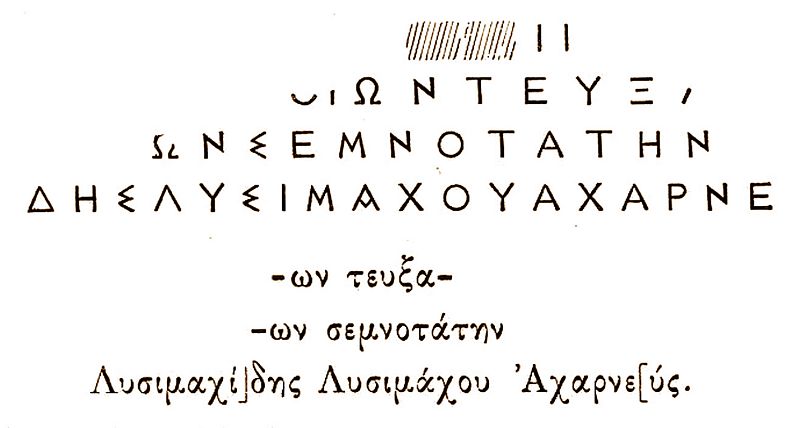

reconstruction. We read:

Fig.1b: Inscription on votive relief No.1. It includes the phrase "Lysimachides Lysimachus son of Acharnae."

(p.238) Line 2 seems

to have been the first two letters op or θρ (roughly άρ]θρων). The form

σεμνότατη makes it very likely that the inscription was written in

metric. A Lysimachides Lysimachus' son of Acharnae (line 3) comes before C.I.A. 11 1924.

2.

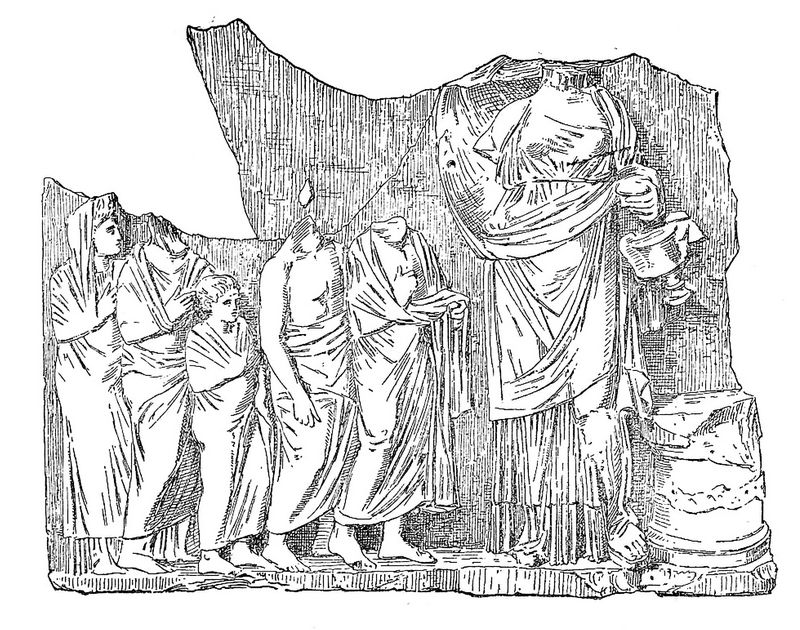

Votive relief (fig. 2) H. 0.32m, W.0.41m. Broken off at the top and

right, a matching piece of the ground was found separately. Left ante,

over which the representation overlaps. Pentelic marble.

Fig.2: votive relief No.2, showing the goddess Hygeia at right with 5 worshippers.

To

the right is a round, wreathed altar, above which one can see the rest

of a hand stretched out from the right, holding a kantharos. The arm to

which this hand belongs did not rest on the relief ground, it was

worked freely and probably attached. To the left of the altar is a

goddess in frontal view (right leg), her head (p.239) and the right

forearm, which used to be particularly attached, are missing. She is

dressed in a sleeveless, belted chiton and a cloak that is pulled over

the back of her head and is held in her right hand at chin level. The

chiton is slightly picked up at the right hip and swells out over the

coat in a small puff. A roughly horizontal line that cuts across the

chiton just above the feet and seems to indicate a doubling of the same

is, I believe, an unintentional saw line. In her left hand the goddess

holds a round box with a flat, domed lid.

Approaching

her from the left are five worshipers, first a man (head missing),

whose cloak covers his arms and leaves only his right hand raised in

adoration and part of his chest uncovered, then a second, also

headless, whose right arm is hanging limply just as the breasts are not

covered by the cloak. A boy follows, fully wrapped in a cloak, and two

women (the one in front without a head) with their hands raised in

adoration, both in chitons and cloaks, which the last one has pulled

over the back of their heads.

Traces of blue survive on the

relief ground, red at the base of the altar, the goddess's chiton, the

foremost man's shoes, the boy's hair and shoes.

The relief

corresponds in composition and workmanship to the mass of those found

on the southern slope of the Acropolis. We may certainly recognize

Hygieia in the goddess; except for the box in her left hand, she agrees

entirely with the Hygieia des Reliefs Duhn (Arch. Zeitung 1877) No. 17

- Sybel 3994; also Duhn 32=Sybel 40 I 3, Duhn 15=Sybel 4009 and Duhn

10=Sybel 4 001 (illustrated Ath.Mitt.

X p. 258) are closely related in the depiction of the goddess. We find

the goddess on all these reliefs in the fuller, more maternal type,

which Koepp (Ath.Mitt. X p.

257 ff.) rightly separates from the youthful one (p. 240) that later

became established [4]. We seldom find the box in her hand, an

attribute that is perfectly suited to the goddess of healing. As far as

I can see, it only appears on the relief Duhn 29 = Sybel 4032 [5].

The

kantharos, which is the only remnant of the deity on the right, is

otherwise not found on the reliefs of this genre. As far as I can see,

this standing attribute of the heroes is never found in the hand of

Asclepius [6]. Asklepios holds a deep kylix on the fine fragment (Duhn

5 = Sybel 4510, reproduced Ath.Mitt

XVII p. 240), which cites Ziehen as an example of the dispensation of

medical aid by the god. But the kantharos on our relief can hardly have

this purpose; if the god offered the healing drink to the mortal, the

worshiper would have to stand closer to the altar and stretch out his

hand for the cup. Here, as on the numerous hero reliefs, the kantharos

serves only to indicate the donation that the god or hero accepts from

the mortal.

3. Fragment

of a votive relief. Broken off at top and left. On the right an ante

over which the depiction extends. H. 0.185m, width 0.10m Pentelic

marble.

In the foreground a sacrificial sheep being led to the

left by a boy standing in the second row, behind him (in the third row)

an adoring woman in a chiton and cloak. She is followed on the right by

a man in a cloak, his chest half bare, his left hand resting on his

hip. The work of the relief is very poor, the condition bad, especially

the heads of the man and the boy are badly damaged.

4. Fragment of a votive relief, chipped on all sides. H. 0.19, W. 0.10m. Pentelic marble (p.241).

Bearded

adorant to the right. The cloak leaves the chest and right arm

uncovered. The upturned head is heavily chipped. the lower legs are

missing.

5. Fragment of

a funeral meal, H. 0.28, W. 0.25m. The old rim survives only on the

right, where it has an antennae shape. Pentelic marble. Found about

1.50m north of the district on the road.

On the right, partly in

front of the ante, stands a large amphora with volute handles, the

lower part of which is badly damaged. A young man follows from the

front on the left, the head, right arm and feet are missing, the

surface of the body is also heavily chipped, the left hand is holding

an indistinct object (drinking horn?). Next to him on the left is a

piece of an overhanging kline with a low table in front of it and small

remains of the hero lying on the kline. We may assume with certainty

that this banquet was set up in the sacred precinct in the immediate

vicinity of which it is found. The cult of the heroized dead tends to

attach itself to the shrines of the healing gods and heroes. In

addition to the finds in the Athenian Asklepieion (cf. Milchhöfer, Jahrbuch II

p. 26 ff.), there are now finds from the cult sites of Amphiaraos in

Oropos and Rhamnus (Λελτίον 1891 p. 1 17 no. 23), and it is certainly

no coincidence that that also in Athens near the Amphiaraos reliefs

(Λελτίον 1891 p. 89 no. 23 f.) a funeral meal has come to light

(Λελτίον 1891 p. 115 no. 5).

6.

Marble slab with female breast in high relief. (fig.4). H. 0.17m, width

0.08m. Pentelic marble. Under the breast on a slightly tapered base is

the inscription:

Fig.3: Votive relief No. 6 with inscription.

The inscription is very

carelessly written and probably belongs to the third century BC at the

earliest. A nail driven between the breast (p.242) and the inscription,

which was used for attachment to the wall or a pillar, caused the lower

part to break off due to its rusting.

7.

Marble slab with male genitals in relief (fig.4). The limb is broken

off. The relief ground was colored red. The plate was nailed to the

wall, as shown by a round hole below the testicles. Height 0.11 m,

width 0.08 m.

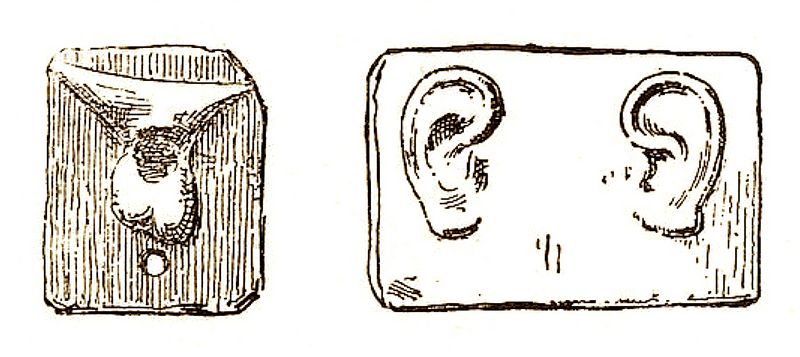

8. Marble slab with two ears in relief (fig.5). Height 0.105 m. Width 0.155m.

Fig.4 (left): Votive relief No.7.

Fig.5 (right): Votive relief No.8 .

9.

Slab of bluish marble, broken off at the bottom. Height 0.23m, width

0.24m. Rearing, bearded snake, of which, in addition to the raised head

and neck, a coiled body has been preserved.

10.

White marble chipped fragment on ring. Height 0.14m, width 0.08m. A

snake curls up on a rock, the head is missing. Probably from a votive

relief.

11. The two anterior phalanxes of a finger which appears to have been consecrated separately. Bluish marble. Length 0.085m.

12. Two limbs of a finger, also consecrated individually. Pentelic marble. L. 0.085m. (p.243)

13.

Statuette of a Goddess. Pentelic marble. Height 0.31m. head, neck, the

right upper arm and the entire left arm were specially attached and are

now missing, including the right arm. Foot and half of the 1st are

broken off. The goddess is dressed in a sleeveless, high-girded chiton

and what appears to be a cloak. Traces of red on the first shoe. Very

rough work, probably from Roman times.

14. Right foot of a statuette of Pentelic marble, Length 0.08m.

15. Forearm of a statuette of Pentelic marble, Length 0.09m.

16.

Ivory statuette, Height 0.075m. Glued back together from many pieces.

The back is not worked, the thighs are badly chipped off, the lower

legs are missing except for a piece of the left one.

A standing,

beardless man. The head is tilted slightly to the right, the arms are

crossed in front of the chest. He wears chainmail over a chiton

and a coat thrown over the left shoulder (cf. Olympia IV. Die Bronzen Taf. LX, N° 984. Antiquites du Bosphore Cimmerien Taf. 27, 4-6. Compte-rendu 1876 Taf. 2,19). Meticulous Roman work.

17. The following terracottas were all found inside the precinct near the ancient entrance:

d)

Archaic enthroned goddess in the usual type. Long curls fall to the

shoulders, both hands resting on the thighs. Height 0.10m.

b)

Seated woman, completely wrapped in the cloak, the right hand in front

of the breast, the left hand in her lap. The head is missing. Remains

of white paint. Height 0.055m.

c) Seated woman of exactly the same type, also without a head. Remains of white paint. Height 0.055m.

d) Torso of a standing woman with a child on her left arm. The heads are missing. remnants of pink. Height 0.065m.

e) Torso of a standing woman in a coat, left hand on her side. The head and lower legs are missing. Height 0.09m. (p.244)

f) Female nude doll with specially attached arms. Height 0.10”.

g) A girl's head intended for use in a figure. Pierced vertically, traces of yellow in the hair. Height 0.04m.

h) Head of the same type, split off behind. Height 0.04m.

Finally, in strata deeper than the old doorstep, a number of sherds of the dipylon type were found.

The

finds prove that the humble district was a place of worship for a long

number of years. Based on the architectural features [7], it can

(according to Dörpfeld) with some probability still be assigned to the

sixth century BC. This probability seems to me to be increased by the

terracottas (especially No. a) [8]. From the fourth century BC we have

the votive reliefs (Nos. 1-5, 10), from more recent times the sculpted

members (Nos. 6-8, 11, 12), and that the sanctuary was still venerated

in Roman times is shown by the reconstruction of the entrance and finds

such as the ivory statuette (No. 16).

If I place the adorant

reliefs around the fourth century BC and the sculpted limbs later, I

think I am justified by the analogy of other sanctuaries of healing

gods. It has long been noted (Koepp, Ath.Mitt.

X p. 263) that the whole mass of votive reliefs from the southern slope

of the castle, which stylistically completely follow those from the

amphiaraia in Oropos and Rhamnus, as well as those from our sanctuary,

come from a relatively (p.245) short period of time.

The

almost sudden breaking off of a class of votive offerings, which for a

certain time enjoyed such great popularity, cannot be explained by a

rapid fading of the bloom of the sanctuary—this is contradicted by the

written testimonies—but we must seek the reasons for this in other

circumstances. Brückner's important proof (Arch. Anzeiger

1892 p. 28) that Demetrius's grave law destroyed the flourishing grave

relief sculpture of Attica at one blow also explains the sudden end of

the votive reliefs. The ban on funerary reliefs cut off the lifeline of

the entire business of Attic relief craftsmen; this whole industry

evidently perished in a short time and the votive reliefs disappeared

with it. The following centuries limited themselves in their sculpted

votive offerings to the more or less crude rendering of the healed

limb, and this type of anathema seems to have become very popular,

particularly in Roman times [9].

If we now put the question to whom these consecrations are

directed, who is the lord of the sacred precinct, the answer is not as

easy to give as it first appears. We do have a dedicatory inscription

to Asklepios, but it is late and, in my opinion, not sufficient to

prove the god to be the proprietor of the sanctuary for earlier

centuries.

We may go further: Asklepios cannot have been the

original lord of the district, for he only came to Athens in the last

decades of the fifth (p.246) century BC. The introduction of the

Asklepios cult in Athens, which Koepp (Ath.Mitt. X p. 255) and

recently also Wilamowitz (Commentarium gramm. IV p. 25, 1) with

convincing reasons place in the time of the Peloponnesian War (cf. also

Wolters, Ath.Mitt.

XVI p.164, 2), can be determined even more

precisely than has been done so far. In The Wasps (v. 122),

Aristophanes does not yet know of any Asklepios cult in Athens, but

Sophocles still celebrates the god in a Paian; the years 422 and 406 BC

given by these two facts have hitherto formed the limits within which

the introduction of the god had to be set [10].

Now, as has long been noted, we have an inscribed report on the founding of the Asklepieion (Köhler in C.I.A.II, 1649, Wilamowitz loc.cit.);

It was Telemachus of Acharnae who introduced the cult of Asclepius in

Athens, and he was not a little proud of this deed (see C.I.A.

II, 1442, 1443, 1649, 1650). If Köhler seems to despair of restoring

the important document C.I.A. 11,1649, this is due to the erroneous

composition of two fragments, which makes the condition of the

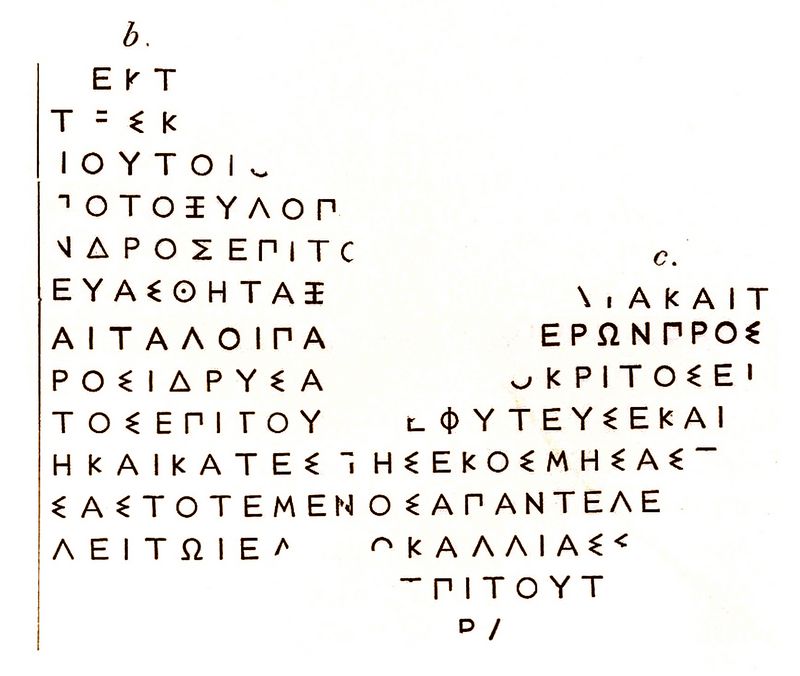

inscription appear much more hopeless than it is. I repeat here the two

fragments b and c according to Köhler's edition, leaving out the side

page, which is unimportant for us:

Fig.6: Inscription with two parts b and c mismatched.

When

the stones were revised, it became clear to me that these fragments,

which seem to fit together so perfectly, do not belong to one another.

Neither the T in line 1 0 nor the N in line 11 can be put together from

the remains on both stones in the same way as was done in the corpus,

both letters would be half too wide. The peculiar coincidence that c

fits so well in sense to b is explained very easily on closer

inspection, in c the same things are repeated almost verbatim as are

also reported in b. The last letters of each line of c are identical to

the first letters of the following line of b, as it turns out:

Z. 6- 7 AIT

» 7- 8 POS

» 8- 9 TOS El

» 9-10 EKAI (Η K AI b)

» 10-11 SAS

» 11-12 AE

If

one crosses out these matching letters in c in Köhler's edition, the

individual lines follow one another and their length can be determined

at 18 letters. We can thus partially supplement b from c Z. 6

Ιπεσκ]ευάσθη τα ξ. ί]ερώνπ|ροσιδρύσατο . . . 6x.pt|τος έττί του στήσε

κοσριηΐσας το τέαενος άπαν τέ|λει.

The repetition was not

exactly verbatim, as is proved (p.248) by the shift of the

corresponding letters of lines 6 and 7 (in c) by two places to the

right and the H at the beginning of line 10 instead of the E to be

assumed after c The reason for the whole repetition is not apparent to

me, but I have no doubts about its existence.

What

is valuable now is that from the correct use of b and c we also obtain

a secure line length of 18 letters for the by far most important

fragment a. The same is [10]:

Fig.7: Inscription part a.

If

we now try to complete the most important lines 10 ff. to 18 letters,

the reading "ούτως ίδρύθη [το ίερό]ν τόδε άπαν επί ............ λο άρχοντος." results

ούτως ιδρύθηκε το ίερόν τόδε άπαν επί ............ λο άρχοντος.

"thus the sanctuary was founded then on ............ the lord."

Who

was the archon named, whose name ends in -λος? In the year 442 BC we

have the archon Diphilos, but this year is much too early, also the

number of letters in the name does not fit, 381 BC we find Demophilos

as the archon, but this year is definitely too late, in the 60 years in

between we only encounter one Archon on -λος, that is the one from 420,

Astyphilos. Here the length of the name and the year fit perfectly and

we can therefore state it as a certain fact that the Athenian

Asklepieion was founded in 420 BC under the archon Astyphilos.

Lines

4-5: Girard's suggestion (L'Asclepieion d'Athenes p.130) ές το

Έλ[ευσίνιον is quite possible "... the Eleusinion"

Line 5 f. I consider οί'κοθε[ν μεταπεμ]ψάμενος to be certain,

οί'κοθε[ν μεταπεμ]ψάμενος "Moved from home to home"

Line

7 is to be read with Köhler -ηγ]αγεν δευρε, and then perhaps line 8 of

Telemacho's name will have to be added in the nominative as a subject.

But there are gaps in between that I haven't been able to fill so far.

On

the other hand, I certainly think I can add Z. 9 άμα ηλθεν Ύγ[ίεια

καί.. . Who else should have come at the same time as the god 'taken

from his homeland' than the goddess, whose first two letters are on the

stone?

So we have as the core of the inscription the sentence:

άμα ηλθεν 'Υγίεια καί ούτως ίδρύθη το ιερόν τόδε άπαν επί Άστυφ ίλου

άρχοντος. [11]

"if Hygieia came and thus founded the sanctuary, then again during the Astyphile reign."

Hygieia came to Athens at the same time as Asklepios, in which Thrämer (Roscher's Lexikon 1 p. 2773) keeps against Koepp (Ath.Mitt. X p. 256ff.), Wilamowitz (Isyllos p. 192 f.) and more recently Blinkenberg (Asklepios og hans Fraender i Hieron ved Epidauros

p. 78) That may be right, but she didn't come from Epidauros, as our

inscription already shows, where her introduction is clearly separated

from that of Asclepius from Epidauros (οϊκοθεν) ("everywhere") (p.250).

Wherever we find the Epidaurian Asklepios family united, Hygieia [12] is

missing in older times.

Thus, in the sacrificial regulations written at the beginning of the fourth century from the Munich Asklepieion (C.I.A.

II, 1651) Iaso, Akeso and Panakeia are assigned their πόπχνα ("dear"),

while Hygieia is not named [13]. Nor do we find them on the relief of

the Athenian Asklepieion published by Ziehen, which offers the

Asklepios family particularly complete and with the inscriptions

Epione, Akeso, laso and Panakeia (Ath.Mitth. XVII p. 243 Fig. 7).

As

Hygieia from the Peloponnese, where i.e.. in Titane her cult is

obviously old (Paus. II 11, 6 and VH 23, 8), came to Athens and

together with Asklepios moved into the sanctuary on the southern slope

of the Acropolis, there she stood next to the Epidaurian family of the

god as one Stranger, she was neither the wife nor the daughter of

Asclepius of Epidauria [14]. So they could call Ariphron (Athens. XV p. 702)

and Licymnios (Sextus Emp. XI 49) as πρεσβίστα μακάρων ("blessed

presbyter") and as λιπαpόmmατε maτερ ("lubricious mother"), which also

explains the oscillation of the votive reliefs between the maternal and

the youthful type. Gradually her relationship to Asklepios was fixed as

a daughter's, and even in the late Paian of Macedonia she was not

completely fused with the other Asklepios daughters (C.I.A. III 171 b).

After

this digression, I return to our sacred precinct. Since Asklepios came

to Athens in 420 BC, the sanctuary cannot have been designed for him

first, as it is undoubtedly older. So the only question is, when did

Asklepios oust an older god or hero here, or did he ever completely

oust him? [15]

The probability that the Epidaurian god was

installed in a second district, so close by, soon after the erection of

his large, splendid sanctuary on the southern slope of the castle, is

not very great. Throughout antiquity, writers and inscriptions only

know of one Asklepieion in Athens (see the testimonies of Curtius, Stadtgeschichte p. XVII), in contrast to the one in Munich (see Δελτίον 1888 p. 132 ff. cf. Bull, de corr. hell.

XIV p. 619) τό έν άστει, and we will not assume a second one for

classical time without absolutely compelling reasons. We know, of

course, that Demon des Demomeles' son, the cousin of the orator

Demosthenes, dedicated his house and garden to Asklepios around the

middle of the fourth century and became his priest (C.I.A.

II 1654 ), but this dedication can - if developed a special

sanctuary out of it — by no means be identical with our sacred area,

which as a sanctuary is considerably older. In addition to the

terracottas already mentioned, the complete absence of old inner walls

already proves that an old private house was not later transformed into

a τέμενος.

One might think that reliefs 1 and 2 are compelling

proof of the age of the Asklepios cult in our district. We see a man

with the head type of Asklepios on one relief, see Hygieia on (p.252)

the other relief, so the conclusion is very close that these reliefs

are votive gifts to Asklepios himself, the god already in the fourth

century BC possessed of a Temenos. The conclusion is obvious, but it is

not permissible, as a consideration of the pictorial tradition teaches.

Asclepius

was not the oldest god of healing that Attic art attempted to depict.

Considerably older than any Attic image of Asclepius and sanctuary

known to us [16] is the small amphiareion at Rhamnus, the excavation of

which is credited to the Greek Archaeological Society. Two small heads

of the god were found here, which Stai's (Δελτίον 1891 p. 117 no. 19

and 50) briefly described. One (No. 19), less well preserved, is still

completely archaic, probably from the end of the sixth century, it is

reminiscent of ancient Zeus heads in the shape of the hair and beard,

the other (No. 50), incomparably more beautiful and better preserved,

is certainly not younger than 430. The full head of hair falls long and

sleek on the nape of the neck, it is swept back from the temples in two

mighty waves, the mustache hangs softly on the strong, slightly curled

full beard, the large eyes are still a little severely formed, the

whole head has something majestic in spite of its small size.

Apparently a special type for the god of healing has not yet been found

here, the Zeus type is simply transferred to him [17]. At the time when

the Epidaurian god was introduced in Athens, the artists of the

Phidasian circle created - one would like to think of Alkamenes [18]

(cf. Overbeck, Gesch. der greich.(p.253) Plastik 4 1 p. 379 and above

all Reisch, Eranos Vindobonensis p. 21 f.) - for him that ideal, which

is a mild, purely humane Zeus ideal [19] ( Brunn, Götterideale p. 96

ff.). In the two types of god enthroned and leaning on his staff, this

ideal absolutely dominates fourth-century Attic reliefs of Asclepius,

but it was not used for Asclepius alone.

Without the slightest

change, the two types of Asklepios are transferred to Amphiaraos, for

whom no separate type develops at all. The sometimes standing,

sometimes enthroned god on the reliefs from Oropos (cf. Berliner

philol. Wochenschrift 1888 p. 259), from Rhamnus (Δελτίον 1891 p. 117

no. 18 and 23), from Athens (Δελτίον 1891 p. 89 no. 23) without knowing

where it was found or the inscriptions, one would have to take it for

Asklepios. Even more, the Attic craftsmen, who were accustomed to

depicting Hygieia alongside Asklepios, also associate the goddess with

the Boeotian hero, whom they equate with their Asklepios, although

Amphiaraos originally has nothing to do with Hygieia [20]. We would

dare to call the goddess Hygieia on the reliefs cited if the name were

not even given to her (Δελτίον 1891 p. 89 no. 23). It is a most

remarkable (p.254) example of the powerful influence which art and its

types exert on the cults.

Hygieia came after Oropos and Rhamnus

only because the Athenian stonemason wanted to add the helpful goddess,

whom he was used to associating with him, in addition to the god of

healing. Indeed, in Oropos she seems gradually to have entered into a

similar, if looser, relation to Amphiaraos as she has to Asklepios in

Athens; we see at least that in the first century BC. of the demos of

the Oropi statues of Metella, Sulla's wife, and a Lentulus Άαφιαράω καί

Ύγιεία ( Έφημερίς άρχ. 1885 p. 102 no. 4. p. 106 no. 6, cf. 1891 p .1

37 [21]

There is a second example of the tenacity with which the

Attic stonemasons clung to the types of relief that had been developed

for Asklepios in relation to related deities, and that is the beautiful

relief from Luku, which Lüders published (Annali

1873 p. 11 4 ff. taf. M. N. Sybel No. 319). At today's Luku Monastery,

Polemocrates, according to Pausanias II 38, 6 a grandson of Asklepios,

had a sanctuary (cf. Lölling in Iwan Müller's Handbuch III p. 166), from which the mentioned relief and another [22] (Sybel 357, badly illustrated Expedition de Moree

111 plate 90) apparently originate; both are undoubtedly Attic in

material and style. Here Polemocrates did not adopt the type of

Asklepios, but the sculptor simply depicted Asklepios with a large

family, and left it to the discretion of the customer which of the two

youths behind Asklepios he wanted to take for Polemocrates. The hero,

to whom the dedication was presumably intended, is thus represented in

his own sanctuary as a secondary figure next to the Attic god. In

addition, there is of course the possibility of interpreting the relief

as a dedication to Asklepios himself; then it would occupy the same

(p.255) place in the sanctuary of Polemocrates as perhaps the

dedication of Hedeia in our Athenian temenos.

For our sanctuary,

the analogy of the Amphiaraus reliefs is particularly important. In

Rhamnus in the third century, the hero Aristomachos is equated with

Amphiaraos; 'Ιεροκλής 'Ιε'ρωνος Αριστοράχω Άριφιεράφ reads the

inscription on the base of his cult hild (Λελτίον 1891 p. 116 no. 14.

Lölling , Αθήνα. III p. 597.1). Aristomachos is again identified in

Marathon with the hero latros [23] (Bekker, Anecdota p. 262.16), and

for the latter Kern ( Έφηαερίς άρχ. 1892 p. 115ff.) has made Eleusinian

origin probable. One sees, therefore, that the Attic healing heroes are

very closely related to one another, despite their different origins,

and the types of the Asklepios reliefs may just as well have been

transferred to any other healing hero as to Amphiaraos [24]. It is

therefore absolutely impossible to see from our reliefs Nos. 1 and 2

which god or hero they are dedicated to. But perhaps the kantharos of

Relief No. 2 speaks for the fact that a hero, not Asklepios, was

actually depicted.

Of the Athenian healing heroes known to us,

two cannot come into question for our district, because their shrines

are fixed in other places in the city. For the Heros latros, who one

would particularly like to think of here, in the vicinity of the

Eleusinion, because of his connections to Eleusis (Έφηρ,ερίς άρχ. 1890

p. 117 f. 1892 p. 115), the location is in the north of the city

secured where the Boreasstrasse now meets the Athenastrasse. Two large

blocks of inscriptions relating to his sanctuary were found there (C.I.A. 11 403 and 404), and the literary evidence (see Gurtius, Stadtgeschichte

S.L) also points there. Furthermore, Amphiaraos, whose cult in Athens

is attested by (p.256) the just mentioned reliefs and the sacral laws

of Lycurgus ( C.I.A. II 162

Z. 21. Add. p. 411) had according to Pausanias 18.2 close to the

eponyms a statue [25]. That he had in the same region a district not

mentioned by Pausanias is shown by the reliefs found near the Theseion

on the prolongation of the Piraeus Railway.

We also know Alkon

[26] from Athenian healing heroes, whose priesthood was held by

Sophocles, whose cult was therefore older than that of Asklepios. It is

very possible that he was the old owner of our district [27]. We must

therefore, in my opinion, leave it undecided for the time being whether

a second Asklepieion was created here in the west of the castle using

an older area, or whether this sanctuary still belonged to another hero

in the fourth century, alongside whom Asklepios was later worshiped

became. It is to be hoped that new excavations will decide this

question.

Athens

Alfred Koerte

Footnotes:

1. See the inventories of Asklepios in Athens C.I.A. II 766 f., of Heros Iatros there C.I.A. II 403, of Arnphiaraos in Oropos C.I.Graeciae Septent. I 303 and 3498.

2.

A relief fragment from the Amphiareion in Rhamnus joins the five pieces

cited by Ziehen as the sixth piece. The god (only the lower body

survives) is seated next to a man lying on the kline, apparently

touching the patient's chin.

3. Bull. de corr. Hell. II p. 89 ff. The concerns that Girard himself later (L'Asclepieion d'Athenes p. 48) raised against his earlier assumption do not seem to me to be valid (cf. Köhler on C.l.A. II 1449. Kern, Έφηρερίς άρχ. 1892 p. 116. Curtius, Stadtgeschichte p. 211).

4. Thrämer (in Roscher's Lexikon

I p. 2780 ff.) wants to recognize epions in all maternal figures,

wrongly so. I will show below how the fluctuation of the Hygieia type

in Attic art can be explained.

5. Duhn and Sybel overlooked them here.

6.

On the Boeotian crater published by Kern (Έφηρερις άρχ. 1890 plate 7) a

healing deity holds the kantharos; but whether the reclining man

represents Asklepios or a healing hero cannot be decided.

7.

To the reasons put forward by Dörpfeld I would like to add the material

of the old threshold, it is the same soft, yellowish porosity from

which the water pipe and parts of the well house of the Enneakrunos are

built (cf. Ath.Mitt. XVII p. 442 f .).

8.

There is no doubt that the 8 pieces listed were dedicated in the

sanctuary given the small space in which they were found.

9. All such dedications to Zeus Hypsistos from the Pnyx Terrace are Roman (C.I.A. III 150-156), as well as those from Melos (Expediion de Moree III Tal. 29.2 cf. pp. 47.1; C.I.A. 2429. Annali 1829 p.342 (Lenormant), 1843 p.332 (Ross)), which is in Wohurn-Abbey Arch. Anzeiger 1864 plate A Fig. 1, a piece which I had the opportunity to see in Oropos, and most of them from the Athenian Asklepieion C. I. A.

III 132 g-k ,p-r, probably also Sybel 4058 and 4730. The somewhat

richer decorated anathemas of Eucrates in Eleusis ( Έφημερις άρχ. 1892

Taf. 5 p. 11 3 ff. Kern) and the Praxias in Athens (Curtius, Atlas of Athens Bl XI. C.I.A. 11,1453), also C.I.A. II, 1482.

10.

line 4 Köhler writes as "I Γ ". I consider the apparently shorter

leg of the P to be an accidental injury to the stone, the horizontal

line clearly extends beyond its base, so the letter was probably Γ not

P; the vertical hash in front of the Γ is not over the middle but over

the right leg of the N in line 5, is therefore not a 1 but a remainder

of an N or H.

11. 1 In the following lines is only understandable 14 ο! ζ]ή[ρ]υχες ήμφεσβ[ητη-σαν χ]ωρίου (see Wilamowitz loc. cit.).

12. Thrämer

op.cit. p. 2774 did not succeed in proving a cult of Hygieia in

Epidauros for the earlier period (cf. Blinkenberg, loc. cit. p. 79 f.). The oldest dedication to Hygieia that we have in Epidaurus (Cavvadias, Fouilles d'Epidaure I

No. 250) dates from about 200 BC. The naming of the goddess on the

Epidaurian coins (see Hes. Lambros, Νομίσματα της Αμοργού' No. 28) is

quite arbitrary, Epione can just as well be represented here.

13. That's why Aristophanes doesn't name her in Plutos, whose healing scene 633 ff. takes place in the Municipal sanctuary.

14.

I do not rule out the fact that she was originally the wife of

Asklepios in Titane and other places (see, for example, the

difficult-to-understand passage of Paus. VII 23.7), also her oldest

representations, e.g. in the votive gift of the Smikythos at

Olympia (Paus. V 26, 2) could very well have been maternal.

15.

The one consecration to Asklepios does not yet prove a complete

suppression, even in the sanctuary of a related god a votive offering

for the healing god κατ' εξοχήν ("par excellance") could once be

donated, especially in recent times.

16. To disregard the

rude, youthful Asklepios das Kalamis in Sicyon (Paus II 10, 3), who

cannot be precisely described and apparently had no influence on the

art of the subsequent period.

17. I would like to believe that

in few surviving heads is there as much of the Zeus of Phidias as in

the little Rhamnuntian head.

18. An Asclepius of Alkamenes is

not attested for Athens, but for Mantinea (Paus. VIII 9, 1). The

standing Asclepius on late coins from Mantinea (see Catalog of the Greek coins in the British Museum.

Petoponnesus Taf. XXXV, 9) goes back to this picture. We know two

representations of the god from Kolotes, a gold ivory slab in Ivyllene

(Strabo VIII, 337) and a relief on the τράπεζα in Olympia (Paus V 20,

1).

19. Amelung's attempt to prove a second ideal of Asklepios from the late 5th century (Florentiner Antiquities

p. 39 ff.) does not seem to have been successful. The beautiful head he

published is probably more of an ideal portrait of a poet than the god

of healing.

20. The fact that in Pausanias' time, together with

Aphrodite, Panacea, Iaso and Athena Paionia, she held one fifth of the

great Amphiaraos altar in Oropos (Paus. I 34,3), of course proves

nothing for an old connection with the god. On this altar are united

all the deities who could possibly be associated with the art of

healing and with Oropos. Its late origin is proven by the remains of

older altars under its foundations (see Πρακτικά

1884 p. 92 Taf. E, Dörpfeld). Where Hygieia has ancient cult, as in

Titane (Paus. II 11.0, VII 23.8), she is connected only with Asklepios.

21. Cf. also C. I. Grxc. Sept. 412 and Ath. Mitt.XII p. 318 no. 418

22. Only the dedicants are preserved on this one.

23. Lölling op.cit. that the Rhamnuntische Amphiaraos also bears the nickname Heros latros.

24. For Trophonios, Pausanias (IX 39.3 and 4) expressly attests that Praxiteles formed him in the Asklepios type.

25.

It is not possible to determine exactly when his cult was introduced in

Athens. The sacral law mentioned calls him before Asklepios — και τω

Άμφιαράω καί τω Άσκληπιω— from which one might conclude that his cult

was of a higher age. However, the fact that Aristopbanes in Amphiaraos,

cited in 415, still seems to send his patient to Oropos speaks against

this. I would like to infer this especially from the ακραιφνές ΰδωρ

(Fr. 32 Kock), because the goodness and coldness of the spring in

Oropos, which still refreshes every visitor to the beautiful forest

valley, is often praised in antiquity (Xenophon Mem. III 13, 3, Athens II p.46c).

26. To refrain from Toxaris; see Sybel Hermes XX p. 41 1Γ.

27. Sybel's attempt to place Alkon on the southern slope of the castle as Asklepios' predecessor (Ath.Mitt.. X p. 97) has been refuted by Wilamowitz, Isyllos S, 189 ff.

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|