|

CHAPTER III

The Sanctuaries that are Outside the Citadel (part 2).

The Amyneion.

The

Amyneion, or sanctuary of Amynos [85], is known to us only through

monumental evidence, brought to light in the recent excavations. Its

discovery is one of the things that make us feel suddenly how much of

popular faith we, relying as we must almost wholly on literature, may

have utterly lost. If

after leaving the precinct of Dionysos in-the-Marshes we follow the

main road for about 35 metres, we come on a precinct (fig.30) of much

smaller size and of quadrangular shape, which abuts on the road and

along the North side of which a narrow foot-path leads up to the

Acropolis. The precinct-walls are of hard blue calcareous stone from

the Acropolis and neighbouring hills, and the masonry is good

polygonal.

Fig.30: Plan of the Sanctuary of Amynos (Ath.Mitt. XXI, 1896 plate xi).

The entrance-gate (A), (p.101) which

has been rebuilt in Roman times, is at the North-West corner. A little

to the East of the middle of the precinct, and manifestly of great

importance, is a well (B). The natural supply of this well was

reinforced by a conduit-pipe, which leads direct into it from the great

water-course of Peisistratos, which will later (p.119) be described.

Near the well are remains of a small herochapel, and within this was

found the lower part of a marble sacrificial table (C), decorated with

two snakes. The masonry of the precinct wall, the well, and the shrine

all point to a date at the time of Peisistratos. Even before the limits

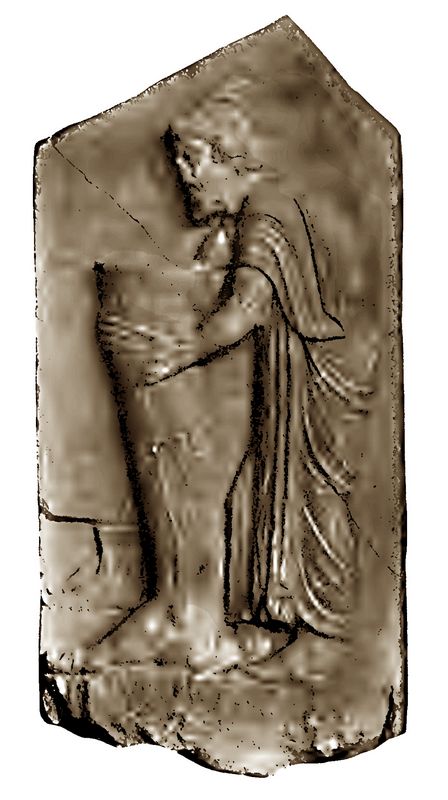

of this precinct were fairly made out the excavators came upon a number

of fragments of votive offerings of a familiar type. Such are reliefs

representing parts of the human body, breasts and the like, votive

snakes, and reliefs representing worshippers approaching a god of the

usual Asklepios type. Conspicuous among these was a fine well preserved

relief (Fig. 31), depicting a man holding ‘a huge leg, (p.102) very

clearly marked with a varicose vein, exactly where, doctors say, a

varicose vein should be. The inscription [86] above the figure is

unfortunately so effaced that no facts emerge save that the dedicator,

the man who holds the leg, was the son of a certain (p.103) Lysimachos,

and was of the deme Acharnae.

Fig.31: Votive relief from Sanctuary of Amynos.

But

now-a-days in the matter of ascription we proceed more cautiously. We

know that votive-reliefs of the ‘ Asklepios’ type are offered to almost

any local hero, that local heroes anywhere and everywhere are

hero-healers [87] . Hence local hero-healers were gradually absorbed

and effaced by the most successful of their number, Asklepios. In

literature we hear little of the hero-cult of an Amphiaraos, but his

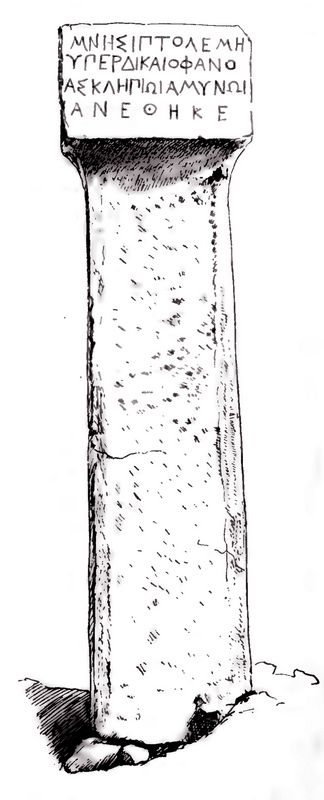

local shrine went on down to late days at Oropus. Fortunately in our

precinct we have inscriptions that leave us no doubt. On a stele

[88] (Fig. 32) found there we have an inscription as follows:

(p104)

‘Mnesiptoleme on behalf of Dikaiophanes dedicated (this) to Asklepios Amynos.’

Fig.32: Stele with inscription from Sanctuary of Amynos.

Sophocles

[91] though, to us, he is first in remembrance, comes last in ritual

precedence; Amynos is first. The history of the little shrine is

instructive. Not later than Peisistratos, and how much earlier we do

not know, the worship was set up of a local hero with the title

Protector, Amynos. At some time or other, perhaps shortly after the

pestilence at Athens, which the local Protector had been powerless to

avert, it was thought well to call in a greater Healer-Hero, Asklepios,

who meanwhile had attained in the Peloponnesos to enormous prestige.

The experiment was tried carefully and quietly in the little precinct. Amynos

kept his own precedence. No one’s feelings are hurt; the snake of the

Peloponnesos is merely affiliated to the local Athenian hero-snake, the

same offerings are due to both, the pelanot, the votive limbs. But the

new-comer is too strong; Asklepios waxes, Amynos wanes—into an

adjective. Asklepios outgrows the little precinct and betakes himself

to a new and grander sanctuary on the South slope.

The precinct

and worship of Amynos, though it has no mention in literature, is

preserved to us perhaps through its association (p.105) with

the dominant worship of Asklepios ; but Amynos was probably only one

among many heroes who had their chapels and their family worships

scattered along the main road of the city where countless little

buildings remain unidentified (Fig. 35). If the supposition suggested

above (p. 99) be correct these local heroes must have had choral dances

about their tombs, those choral dances affiliated by the late-comer

Dionysos, and ultimately leading to the development of the drama. At

the festival of the Anthesteria these local ghosts would be summoned

from their tombs on the day of the Pithoigia; on the day of the Chytroi

they would be fed and their descendants would hold a wake with revels

and dancings.

The Sanctuary of the Semnae Theai or Venerable Goddesses.

The site of this sanctuary is practically certain. Euripides [92] in the Electra

makes the Erinyes, when they are abeut to become Semnae, descend into a

chasm of the earth near to the Areopagos. Near to the Areopagos there

is-one chasm and one only, that is the deep fissure on the North-East

side, the spot where tradition has long placed the cave of the Semnae

[93]. A cave they needed, for they were under-world goddesses. Their

ritual I have discussed in detail elsewhere [94]; here it need only be

noted that it was of great antiquity and had all the characteristic

marks of a chthonic cult. As under-world goddesses the Venerable

Ones bore the title also of Arai, Imprecations; they were for cursing

as well as blessing ; the hill it is now generally acknowledged took

its name from them rather than from the war-god Ares. Orestes it will

be remembered [95] came to the Areopagos to be purified from his

mother’s blood, and he found the people celebrating the Choes; he found

them, if our topography be correct, close by, in the precinct of

Dionysos-in-the- Marshes.

The Sanctuary of Aphrodite Pandemos.

Harpocration

[96] in explaining the title Pandemos tells us that Apollodorus in the

sixth book of his treatise About the Gods said that this was ‘the name

given at Athens to the goddess whose worship had been established

(p.106) somewhere

near the ancient agora.’ His conjecture that the goddess was called

Pandemos because all the people collected in the agora need not detain

us, but the topographical statement coming from an author who knew his

subject like Apollodorus, is important. We have to seek the sanctuary

of Pandemos somewhere on or close to the West slope of the Acropolis,

somewhere near the great square which as we shall see (p. 131) stood in

front of the ancient well-house and formed the ancient agora.

Pausanias

[97] mentions the worship of Aphrodite Pandemos in a sentence of the

most tantalizing vagueness. After leaving the Asklepieion he notes a

temple of Themis and in front of it a monument to Hippolytus. He then

tells at length the story of Phaedra and next goes on ‘When Theseus

united the various Athenian demes into one people he introduced the

worship of Aphrodite Pandemos and Peitho. The old images were not there

in my time, but those I saw were the work of no obscure artists.’

Immediately after he passes to the sanctuary of Ge Kourotrophos and

Demeter Chloe and then straight to the citadel.

Of the actual

sanctuary of Aphrodite Pandemos not a trace has been found. From the

account of Pausanias coupled with that of Harpocration we should expect

it to be somewhere below the sanctuary of Ge and above the fountain

Enneakrounos, near which was the ancient agora, and of course outside

the Pelargikon. When the West slope of the Acropolis was excavated [98]

in the upper layers of earth about 40 statuettes of Aphrodite were

found, and these must have belonged to the sanctuary. Inscriptions

[99] relating to her worship were found built into a mediaeval

fortification wall near Beule’s Gate. These, as not being in situ,

cannot be used as topographical evidence, but they give us important

information as to the character of the worship of Pandemos.

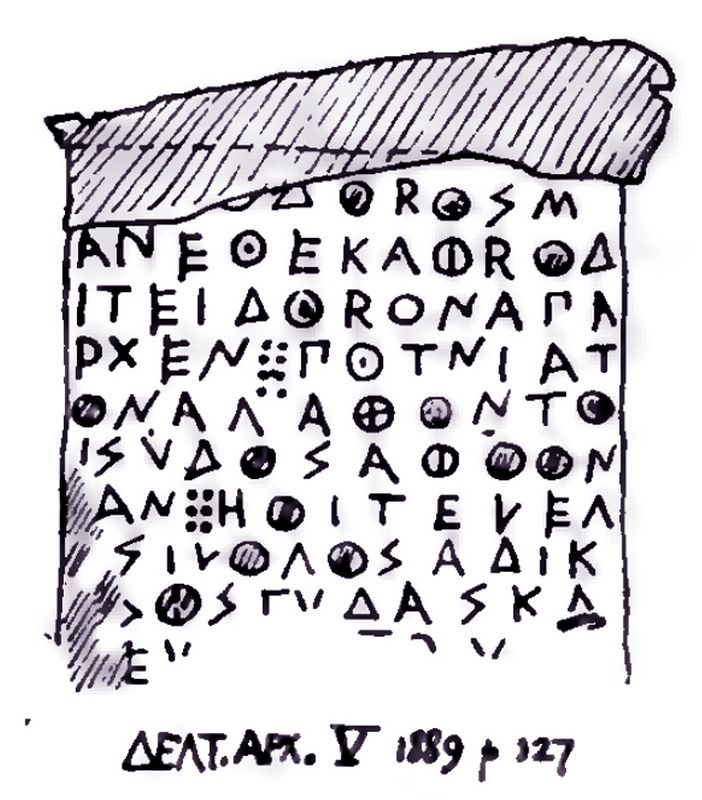

‘[...]dorus dedicated me (p.107) to

Aphrodite a gift of first fruits, Lady do thou grant him abundance of

good things. But they who unrighteously say false things and....’

Unfortunately here the inscription breaks off so the scandal will

remain for ever a secret. Aphrodite, it is to be noted, is prayed to as

a giver of increase. She does not seem yet to have got her title of

Pandemos, but as this occurs in the two other inscriptions found with

this one, and they probably all three came from the same sanctuary, this Aphrodite is almost certainly she who became Pandemos.

Fig.33: Insciption from early 5th c. BC dedicated to Aphrodite Pandemos.

The

second inscription (Fig. 34), dating about the middle of the 4th

century B.C., is carved on an architrave adorned with a frieze of doves

carrying a fillet, The architrave is broken midway. Only the left-hand

half is represented in the figure. This inscription [101] again is

partly metrical, forming an elegiac couplet.

Fig.34: Inscription on architrave from 4th c. BC dedicated to Aphrodite Pandemos.

‘This for thee, O great and holy Pandemos Aphrfodite,

We adorn with gifts, our statues.’

Beneath

in prose and in smaller letters come the names of the dedicators.

Pandemos is here quite plainly the official title of the

goddess.

(p.108)

The

third and latest inscription [102] is carved on a stele of Hymettus

marble. It is exactly dated (283 B.c.) by the archon’s name, the elder

Euthios. It records a decree made while a woman called Hegesipyle was

priestess. The decree, which is too long to be here quoted in full,

ordains that the astynomoi should at the time of the procession in

honour of Aphrodite Pandemos ‘ provide a dove for the purification of

the temple, should have the altars anointed, should give a coat of

pitch to the roof and wash the statues and prepare a purple robe.’

Aphrodite

Pandemos was a ‘great and holy goddess,’ giver of increase. She was no

private divinity of the courtesan; the second inscription tells us that

she was worshipped by a married woman, who is her priestess. It is

literature and not ritual that has cast a slur on the title Pandemos;

the state honoured both her and Ourania alike ‘according to ancestral

custom.’ Plato [103] In his beautiful reckless way will have it that

because there are two Loves there are two Goddesses, ‘the elder one

having no mother, who is the Heavenly Aphrodite, the daughter of

Ouranos; to her we give the title Ourania, the younger, who is the

daughter of Zeus and Dione, and her we call “ Of-all-the-People,”

Pandemos.’

The real truth was that Aphrodite came to the Greeks

from the East and like most Semitic divinities she was not only a

duality but a trinity.

When Pausanias [104] was at Thebes he saw

the images of this ancient Oriental trinity and he knew whence they had

come. ‘There are wooden images of Aphrodite at Thebes so ancient that

it is said they were dedicated by Harmonia and that they were made out

of the wooden figure-heads of the ships of Cadmus. One of them is

called Heavenly, another Of-all-the-People, and the third the

Turner-Away.’ The threefold Aphrodite came from the Semitic East

bearing three Semitic titles: she was the Queen of Heaven [105], she

was the Lady of all the People, Ourania and [p.109] Pandemos,

what the third title was which the Greeks translated into Apostrophia

we do not know; as already noted it took slight hold. At Megalopolis

[106] we see how the third title of. the trinity faded. There close to

the house where was an image of Ammon made like a Herm and with the

horns of a ram, there—significant conjunction—was a sanctuary of

Aphrodite in ruins, with the front part only left and it had three

images, ‘one named Ourania the other Pandemos, the third had no

particular name. So it was that the Greeks lost the trinity and kept,

all they needed, the duality.

The

Greeks themselves always knew quite well whence came their Heavenly

Aphrodite, she of Paphos, and she of Kythera. Herodotus [107] is

explicit. He is telling how some of the Scythians in their passage

through Palestine from Egypt pillaged the sanctuary of Aphrodite

Ourania at Ascalon. ‘This sanctuary, he says, ‘I found on enquiry is

the most ancient of all those that are dedicated to this goddess, for

the sanctuary in Cyprus had its origin from thence, as the Cyprians

themselves say, and that in Kythera was founded by Phenicians who came

from this part of Syria. Pausanias [108] says ‘the first to worship

Ourania were the Assyrians, next to them were the dwellers in Paphos of

Cyprus, and the Phenicians of Ascalon in Palestine. And the inhabitants

of Kythera learnt the worship from the Phenicians.’

The

Oriental origin [109] of Ourania, Queen of Heaven, the armed goddess,

the Virgo Caelestis, was patent to all; but Aphrodite in her more human

earthly aspect, as Pandemos, goddess of the (p.110) people and of

all increases,as so like Kourotrophos, like Demeter, that she might

easily be thought of as indigenous. Yet her ritual betrays her. For the

purification of her sanctuary we have seen there was ordered a dove.

Instinctively we remember that when Mary Virgin [110] went up to the

temple of Jerusalem for her purification she must take with her ‘a pair

of turtle-doves or two young pigeons. In the statuettes of Paphos,

Aphrodite holds a dove in her hand; the coins of Salamis in Cyprus are

stamped with the dove [111]. At the Phenician Eryx when the festival of

the Anagogia [112] came round, and Aphrodite Astarte went back to her

home in Libya, the doves went with her, and when they came back at the

Katagogia, a white multitude, among them was one with feathers of red

gold, and she was Aphrodite.

85. Ath. Mitt. 1896, XXI, p. 286, pl, xi.

86. ων τευξα-

—wy σεμνοτάτην.

Λυσιμαχι]δῆς Λυσιμάχου ᾿Αχαρνε[ύς, See Dr Koerte’s discussion of the relief, A, Mitt. 1898, p. 235,

87. See my Prolegomena, p. 349.

88. Koerte, A. Mitt, 1896, xxi. p. 295 Μνησιπτολέμη ὑπὲρ Δικαιοφάνου[5 ] ᾿Ασκληπιῷ ᾿Αμύνῳ ἀνέθηκε.

89.

Koerte, op. cit. p. 299... δεδόχθαι τοῖς ὀργεῶσι ἐπειδή εἶσιν ἄνδρες

ἀγαθοὶ περὶ τὰ κοινὰ τῶν ὀργεώνων τοῦ ᾿Αμύνου καὶ τοῦ ᾿Ασκληπιοῦ καὶ

τοῦ Δεξίονος....

90. line 15 ἀναγράψαι δὲ τόδε τὸ ψήφισμα ἐν

στήλαις λιθίναις δυοῖν καὶ στῆσαι τὴν μὲν ἐν τῷ το] Δεξίονος ἱερῷ τὴν

δὲ [ἐν τῷ το(0)᾿Αμύνου καὶ ᾿Ασκληπιοῦ.

91. the worship of Sophocles, see my Prolegomena, p. 346.

92. Eur. El. 1271.

93. Myth. and Mon. Anc. Athens, 11. p. 554.

94. Prolegomena, pp. 239—253.

95. Athen. x. 437.

96.

Harp. s.v. Πάνδημος "Agpodirn... ᾿Απολλόδωρος ἐν τῷ περὶ Θεῶν πάνδημόν

φησιν ᾿Αθήνῃσι κληθῆναι τὴν ἀφιδρυθεῖσαν περὶ τὴν ἀρχαίαν ἀγοράν....

97. Paus. I. 22. 3.

98. Dorpfeld, A. Mitt. 1896, p. 511.

99. Foucart, Bull. de Corr. Hell. 1889, p. 157.

100. The facsimile is from Δελτίον 1889, p. 127. The inscription reads as follows:

...]dwpos μ᾽ ἀνέθηκ᾽ ᾿Αφροδίτην δῶρον ἀπαρχήν.

Πότνια τῶν ἀγαθῶν rat] σὺ δὸς ἀφθον[(]αν.

οἵ τε λέγίου]σι λόγους ἀδίκως ψευδᾶς K...EK...

It is discussed with the two that follow by Mr Foucart, Bull. de Corr. Hell. 1889, p. 157.

101. Τόνδε σοὶ, ὦ μεγάλη σεμνὴ Πάνδημε ᾿Αφρ[οδίτη]

[κοσἹμοῦμεν δώροις εἰκόσιν ἡμετέραις

᾿Αρχῖνος ᾿Αλυπήτου Σκαμβωνίδης, Μενεκράτεια Δεξικράτους

Ἰικαριέως θυγάτηρ, ἱέρεια τῆς [’Adpodirys],...

. AleEtxparous ᾿Ικαριέως θυγάτηρ, ᾿Αρχίνον δὲ μήτηρ.

For discussion of this inscription and the nature of the building dedicated, see

Dr Kawerau, ‘Die Pandemos-Weihung auf der Akropolis’ (A, Mitt, 1905), which

through his kindness reached me after the above was written.

102. ἡ πομπὴ τῆι ᾿Αφροδίτηι ret ἸΠανδή-

μωι παρασκευάζειν εἰς κάθαρσιν

τ]οῦ ἱεροῦ περιστέραν καὶ περιαλε[ϊ-

Wat] τοὺς βωμοὺς καὶ πιττῶσαι τὰς

ὀροφὰΞ] καὶ λοῦσαι τὰ ἔδη παρασκευ-

άσαι δὲ κα]ὶ πορφύραν ὁλκὴν + + ["-

See B.C.H. 1889, p. 157, and Myth, and Mon. Anc. Athens, p. 331.

103. Plat. Symp. 180p. For Aphrodite Ourania, see Myth. and Mon. Anc. Athens,

p. 211.

104. Paus. IX. 16, 3.

105.

I follow M. Victor Bérard, Origine des cultes Arcadiens, p. 142.

Ourania is ‘Queen of Heaven,’ xxxxxxxxxxx, as in the Hebrew scriptures,

Jerem. vii. 18, xliv. 18—20. Pandemos is yyyyy, lady of the land. I

have ventured above, p. 54, to suggest that to the armed Ourania, the

Virgo Caelestis, we owe at least some

elements in the armed Athena.

106. Paus, VIII. 32. 2.

107. Herod. I. 105. The name Kythera is Semitic ((9N5); see M. Victor Bérard,

Les Phéniciens et V Odyssée, p. 427. Kythera means a headdress, a tiara, and its

Greek ‘ doublette’ is Skandeia.

108. Paus, I. 14. 7.

109.

We have incidentally curious evidence of the association of

Kourotrophos with the Oriental Aphrodite. An inscription (C.I.A. ur.

411) found on a Turkish wall near the temple of Nike mentions the

entrance to a chapel of Blaute and Kourotrophos (εἴσοδος πρὸς σηκὸν

Βλαύτης καὶ Kouporpépov). Lydus (de Mens. τ. 21), on the authority of

Phlegon, tells us that Blatta was ‘a title of Aphrodite among the

Phenicians’ (καὶ βλάττα δέ, ἐξ ἧς τὰ βλάττια λέγομεν, ὄνομα ᾿Αφροδίτης,

ἐστι κατὰ τοὺς Φοίνικας ὡς ὁ Φλέγων ἐν τῷ περὶ ἑορτῶν φησί). He does

not tell us,—what is obvious enough,—that Blaute and Blatta are Greek

attempts to reproduce Baalat . (Ὁ). Blaute is but Aphrodite-Pandemos,

Lady, Baalat of the People.

110, Luke ii. 24.

111. Mr E. Babelon, Monnaies des Phéniciens, cxxv.

112. Ael. Nat. Anim. 1v. 2; see M. Victor Bérard, Cultes Arcadiens, p. 106.

[Continue to Chapter 4]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|