|

The Erechtheion at Athens

[Article originally published in 1885 in Papers of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Volume I, 1882-1883, pp. 213-236.)

Introductory Note.

So

much has been written upon the Erechtheion that I have hesitated to

swell the list of writers upon the subject. I hope, however, that my

article may be of some slight service to those who wish to understand

the arrangement of this remarkable building. I take pleasure in

expressing my thanks for kind suggestions to Dr. Wilhelm Dorpfeld, of

the Imperial German Archaological Institute at Athens, and Mr. Francis

H. Bacon, of the American Expedition to Assos. There are some questions

relating to the Erechtheion which can be settled, if at all, only after

more complete and careful excavations than have yet been made. It is

greatly to be desired that this task should be undertaken soon by some

one of the Archeological Institutes in Athens.

The Erechtheion

was the most venerated temple of Athens, con-taining the sacred olive

of Athena (Paus., I. 27, 2), the well of Poseidon (Paus., I. 26, 5),

and the ancient statue of Athena, which was said to have fallen from

heaven (Paus., I. 26, 6; Corpus Inscript. Graec.,

No. 160). No fixed date can be given for either the beginning or the

completion of the present edifice. The older temple was burnt by the

Persians in 480 BC (Herod., VIII. 53 and 55 ; Paus., I. 27, 2). When

the Athenians returned to their ruined city, it is highly probable that

one of their first undertakings was to rebuild the sacred structure in

some way; but no definite record of the erection of any such building

remains. But Herodotus (VIII. 55) says of the Acropolis of Athens, ἔστι

ἐν τῇ ἀκροπόλι ταύτῃ “Epeyfeos τοῦ γηγενέος λεγομένου εἶναι νηός, Which

seems to mean that when He-rodotus wrote, in the early part of the

Peloponnesian war, a building called the temple of Erechtheus stood on

the Acropolis. The inscription in C.I G., 160, and C.I. A., I. 323, bears the date of the archonship of Diocles (Olymp. 92, 4 ; 408 BC); and that in C.I.A., I. 324, dates from Olymp. 93, 1; 407 BC. At this time the temple was clearly approaching completion.

Xenophon (Hellen.,

I. 6, 1) (p.216) says that “the ancient temple of Athena” (6 παλαιὸς

τῆς ᾿Αθηνᾶς νεώς) in Athens was set on fire in the archonship of

Kallias, the year when Kallikratidas succeeded Lysander as Spartan

admiral, i.e., in 406-405 BC. It has been maintained that by the

expression 6 παλαιὸς νεώς the Erechtheion cannot be meant, as a temple

not yet com-pleted could not be called “ancient” ; but the word νεώς is

used to signify not only the building, but the sacred site together

with the building. The Erechtheion is constantly called ὁ ἀρχαῖος νεώς (Schol. in Arist. Zys:, 273; Strabo, IX. 396; C.I.A.,

II 464) james expression παλαιός is certainly justifiable, even if we

do not assume, what is not unlikely, that some part of the ancient

building may have been preserved. Whether the Erechtheion was very much

injured by the fire of 406 BC we have no means of determining ; nor

have we any records of subsequent repairs. The temple is mentioned by

several ancient writers, but none except Pausanias attempt to give a

description of it.

In early Christian times, as the remains

show, the building was used as a church, probably of the Saviour, τοῦ

Σωτῆρος (cf. Mommsen, Athenae Christianae, Ὁ. 40; Pittakis, Eph. Arch.,

No. 1102 sq., p. 640 sq., and No. 1204, p. 742), and divided into a

nave and two side aisles. Under the Turks it was used as a

dwelling-house (Wheeler, Journey into Greece,

p. 364), and also as a powder magazine. When Stuart and Revett saw the

building (1751-1753), it was already in a very ruinous condition.

During the war of Greek independence (1821-1828), the Erechtheion

suffered greatly. In 1838 the building was repaired under the direction

of Pittakis ; but a violent storm in 1852 threw down all but one of the

columns of the western wall, and they are now lying in the interior of

the building. The latest excavations, made in 1852, left the

Erechtheion in its present condition.

For Inscriptions, see Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum, No. 160; Corpus Inscriptionum Atticarum,

1. Nos. 321, 322, 324; ᾿Αθήναιον, VII. p.+ 482; ᾿Εἰφημερὶς

᾿Αρχαιολογική, November, 1837 (Rangabé) ; Avzstblatt, 1836, No. 39 ff.

(Ross) ; Antiguités Helléniques, 1842, No. 56 ff. (Ran-gabé) ; C. T. Newton’s Collection of Ancient Greek Inscriptions in the British Museum, London, 1874; and Otto Jahn’s Pausaniae Descriptio Arcis Athenarum,

ed. 2, revised by Michaelis. Bonn, 1880. On the excavations of 1832 and

the following years, see ’"E@npepis “Apxato- λογική; Awnstblatt, 1835,

No. 78; Allgemeine Zeitung, July, 1835.

The four plans of the

Erechtheion given with this paper are taken from the ἸΤρακτικά of the

Archeological Society of Athens, 1853.

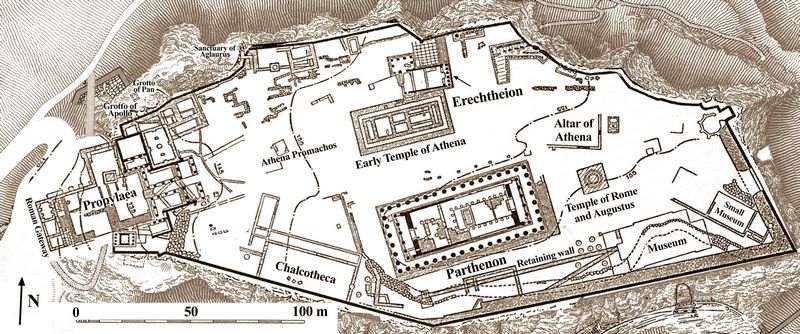

Fig.1a: Location of the Erechtheion on the Acropolis in Athens (after Dorpfeld).

The Erechtheion.

The

Erechtheion (fig.1a) is a rectangular edifice 20.30 m. in length and

11.21 m. in breadth. Seen from the east, it has the appearance of an

Ionic hexastyle temple. The southern wall stands half a metre from a

terrace about 3 m. high, which is continued for some distance both east

and west of the building. The space between this terrace and the wall

of the Erechtheion is filled with earth, On account of this

arrangement, the building appears about 3 m. lower from the south than

from the north, where there is no terrace. The eastern front of the

building is on the same level as the southern side, while the

stereobate of the north and west sides is about 3 m. lower than that of

the east and south sides. At the north-west corner is a portico with

six Ionic columns, four on the front, and one behind each corner

column.

At the south-west corner is a small porch, the roof of

which is supported by six Κόραι (maidens) or Karyatids standing on the

high wall which encloses the porch. Each of these two porches

communicates by a doorway with the interior of the building. Besides

these two doors and the main entrance at the east, there is another

door under the base of the second (counting from the south) of the

engaged columns of the western wall. The antiquity of this last door

has been doubted on account of the roughness of its sides and the fact

that the threshold is not made, as we should expect, of one

stone. The lintel, however, is formed of one block, equal in

height to two courses of the stones of which the temple is built, and

it extends the same distance on each side of the door. As this stone

could have been inserted for no other purpose than as a lintel, the

antiquity of the door admits of no reasonable doubt. (See Plate II, a.)

The rough work on the sides may date from the time when the Christians

used this as the main entrance to their church.

In the

interior of the building are the foundations of three walls. One was a

cross-wall from north to south, just east of the great (p.220) doorway

R, which opens upon the northern porch F. The other two ran at right

angles to the first, extending from it to the east end of the building

[1]. The first of these walls was part of the original building. The

two others were late additions, built probably by the Christians to

support the pillars by which the nave, of the church was separated from

the side aisles, and their late date is evident from the workmanship.

The space from the ancient cross-wall to the western wall of the

building is occupied by a cistern, which was once covered by a brick

vault [2].

This vault, a small part of which is preserved,

rises above the threshold of the great northern door, and was, of

course, not a part of the original building. This fact has led many to

affirm positively that the cistern itself was a late addition. This,

however, is not the case. The two upper steps of the western

stereobate, instead of being formed by two layers of stones, consist of

one course of blocks about 0.45 m. thick. These blocks are not cut off

so as to form part of the surface of the wall within the building; but

they project over the edge of the cistern. They are now roughly broken

off, so that none of them project more than 0.20 m.; but this is enough

to show that these heavy blocks were not employed without a purpose.

Now

the only possible purpose of such blocks can have been to bridge over a

hollow space. The space occupied by the cistern was therefore always

hollow. The cistern itself is partly cut out of the solid rock, and it

was evidently very carefully made. Everything speaks for its antiquity;

and the only argument to the contrary, the height of the brick vault

which at one time covered it, falls to the ground as soon as it is

shown that the original covering was not the brick vault, but the

horizontal pavement of heavy marble blocks, portions of which are still

to be seen projecting over the edge of the cistern. It seems therefore

hardly possible to deny that the cistern is as old as the blocks ; that

is, as old as the building. This cistern was probably the θάλασσα (sea)

of Poseidon.[3]

The wall d, on the eastern side of the cistern,

built of the so-called Piraic stone and founded upon the solid rock,

supported the cross-wall A. Directly above this, in the eleventh and

fourteenth courses (p.221) of the northern wall,[4] are projecting

stones, 0.65 m. in width, to which corresponds a hole, also 0.65 m.

wide, in the southern wall.[5] The present wall east of the cistern was

then the foundation of a wall of some sort, probably of the same age as

the temple, which divided the building from top to bottom.

There

was a second cross-wall about half way between the last-mentioned wall

and the eastern front of the temple.[6] At this point the stones of

both the north and south wall show clearly that a cross-wall existed,

for their surfaces were evidently prepared to receive such a wall;[7]

but no foundations remain.

The Erechtheion was thus divided into

three parts, the two eastern rooms being nearly equal in size, while

the western division was much. narrower than the others. The eastern

apartment had its entrance from the east, while the other two must

generally have been entered through the great door opening on the

northern portico. There was the same difference of level between the

floors of the rooms to which these entrances gave admission which has

been noticed between the entrances themselves. There was no basement

under the eastern cella, nor was the building in any part two-storied.

The floor of the eastern cella was raised one step above the threshold,

and joined the side walls where they are patched with modern brick

work. (Pl. III.) If it had been lower than this, it must have left

visible traces ; and it is hardly conceivable that it should have been

higher.

The space under this floor was filled with a

foundation of Piraic stone like that now remaining in the corners. When

the Erechtheion was altered to suit the demands of the Christian

worship, the floor of the whole edifice was placed at the level of the

ancient floor of the two western divisions. All the inner foundations

of the eastern cella were torn away, except a few stones in the corners

; and part of the foundation of the eastern porch was removed to make

room for the apse of the church (Pl. I, vy). The Piraic stones which

remain show by their position, as well as by their dressed edges, that

they did not originally form the face of a wall, but were embedded in a

solid foundation, which probably filled all, or at least a great part,

of the space under the floor of the eastern cella (cf. Borrmann in Ath.Mitt.1881,

p.383). Moreover, (p.222) whereas the northern and southern walls of

the building west of the eastern cross-wall are both of marble down to

the level of the floor of this part, east of the eastern cross-wall

they are built of marble only where they can be seen from the out-side,

since they were not intended to be seen from the inside below the level

of the eastern entrance. (See Plates III and IV)

There is no

good reason for supposing that the building had two stories west of the

eastern cross-wall, where the floor was lower. Carl Botticher, the

chief supporter of the theory of two stories, says that the faces of

some of the stones of the southern wall show that there was a division

into two stories (Bericht, p.

199 ff.). I can only say that I have been unable to find any traces of

such a construction, nor has any one since Botticher been able to

discover any.

In the north and south walls are five small

slits or windows, which Botticher calls cellar windows, and which he

uses as a chief argument for his theory. He says : “ Wo

Souterrain-Fenster sind, muss auch ein Souterrain dahinter vorhanden

sein ;” but, as has been justly remarked, before we prove the existence

of a cellar from cellar windows, we must first be sure that we have the

cellar windows. I am strongly of the opinion that these openings are

neither cellar windows nor ancient windows at all. They were not made

by the builders of the temple, for they are not found at the joints

between the blocks, but in the middle of the blocks. It would be no

more difficult to cut them here than at the joints, after the stones

were in place ; but the original builders would surely have left such

openings between the stones when they put them in place, as was done in

the case of the similar openings in the stoa of Attalus, in the Arsenal

of Philon, and elsewhere.

Besides, the inferior work-manship

of these openings makes it highly improbable that they belonged to the

original building. It is not unlikely that they were made by the

Christians to light the side aisles of their church, a purpose for

which similar openings are still in use. While then there is no valid

argument for the theory that the Erechtheion was a two-storied building

in any part, the rough Piraic stones below the eastern cella show

plainly that there at least such a division into stories did not exist.

The eastern cross-wall was probably a solid wall, with a door

near the southern end. At this point the Piraic stones of the southern

wall give place to marble; not, however, all at once on the same

ver-tical line, but each course of Piraic stone is continued further

than (p.223) the one above it, giving it the appearance of a flight of

steps. (See Plate III) This arrangement makes it probable that the

steps connecting the eastern cella with the rest of the edifice were at

this point ; though, as there are no actual traces of them, we may

suppose them to have been built of wood. There must have been some mode

of communication between the eastern cella and the rest of the building

; and this seems the most probable place for the stairs.

Fig.1: Northern wall of the Erechtheion at the juncture with cross-wall (after Borrmann 1881).

The

western cross-wall was not a solid wall, like the eastern one. Fig.1,

copied from Borrmann, gives a view of the northern wall where it was

joined by this cross-wall. In the eleventh and fourteenth courses of

stone are still seen the rough ends of the stones of the cross-wall (ε,

ε) projecting from the main wall. Below these the wall is

roughened, as if a wall had been built against it here; but this rough surface

is

only half as wide as the projecting stones above. Up to these stones,

then, the wall had only half the thickness which it had above. It is by

no means improbable that, as Julius suggests, this division consisted

of little or nothing more than a

row of columns with an architrave,

in which case there would mereiy have been an anta set up against the

wall where the roughness is. This appears all the more probable from

the nature of the roughening of the stones. They do not seem to have

projected so as to form part of a cross-wall, except those of the

eleventh and fourteenth courses, but are merely roughened on the

surface.

The western wall of the Erechtheion was not solid in

its upper portion, but had four openings in it, — one between each pair

of engaged columns, and one between the southern column and the anta

which adjoined the southern portico. This last opening is shown to have

(p.224) ‘existed by the finish of the anta. The first three

courses of stone above the line of the bases of the engaged columns

have dressed joints, showing that a wall 0.29 m. thick was built

against them ; but above this point there is no trace of any wall. This

agrees with the inscription ( Αθήναιον, VII. p. 482), διαφάρξαντι τὰ

μετακιόνια τέτταρα ὄντα τὰ πρὸς τοῦ ΠΠανδροσείου. In the drawings of

Stuart and Inwood this space is left open, and it seems never to have

been built up. The purpose of this opening may have been to admit light

to the singular niche in the southern wall close to the corner anta.

This niche is 1.72 m. long and 0.36 m. deep, and reaches from the line

of the top of the western wall to the top of the building ; 2.6.,ὄ it

is about 3.40 m. high. (See Fig. 2.)

Fig.2: Southwest anta and niche (after Borrmann 1881).

The

stones which form its back are not smoothed, but are finished as if for

the reception of a coating of stucco. The large stone just below the

niche is roughly hewn off, and seems to have projected to form a

platform, upon which a statue may have stood. There is no reason to

suppose that there was any room or flooring in front of this niche

beyond the projecting shelf just mentioned. As Borrmann suggests (Ath.Mitt.

1881, p.387), the opening between the southern column of the western

wall and the corner anta is in painful disagreement with the windows

between the columns, which are represented by Stuart and others, and

leads us to doubt whether these windows, as seen by Stuart, were part

of the original plan of the building. This doubt is strengthened by the

fact that the window casings were almost too large for the space.

between the columns, inasmuch as they seem to have projected so

far as to hide part of the fluting. Moreover, where the window cases

were fitted in, the columns are hewn away more roughly than elsewhere.

It is, on the whole, probable that all four openings in the western

wall were originally alike, and that the windows were inserted at some

subsequent period.

(p.225) In the western wall, in the corner

where the temple meets the terrace wall which runs under the porch of

the Κόραι, is a large break in the wall, now filled with rough

modern masonry. A break at this point was part of the original design,

as is shown by the fact that the whole length of the modern masonry is

spanned by one gigantic stone (Plate II., 2), which extends the same

distance north and south of the break. This great stone was intended to

hold up the superincumbent weight of the anta; but this would not have

been necessary if the place now filled with the rubble masonry had been

originally part of the solid wall.

If, as has been maintained by Murray (Journal of Hellenic Studies,

1. 224), Borrmann, and others, the present rubble work marks the place

where a broad flight of steps joined the building, the large

lintel-like stone was quite unnecessary, for the stairs, with their

foundations, would be built into the wall as solidly as any other

stones, and would serve like other stones to support the weight of the

anta. Nor is there anything in the disposition of the stones of the

terrace or those of the portico to show that a flight of steps existed

here ; though it does seem very probable that the terrace was continued

at least one course of stone further to the north than it now is. On

the other hand, if some building joined the Erechtheion at this point,

it would be necessary to keep off the weight of the anta from the

smaller building, and the great stone (Plate II, 2) would then be of

use.

What the shape of this building may have been, whether it

was a long stoa, as suggested by Fergusson, or merely a small edifice

which occupied the corner, it is impossible to tell, as no foundations

have been found. It is very desirable that this corner be thoroughly

and carefully excavated. On the western end of the porch of the Kopa,

the egg and dart moulding of the railing stops about half way between

the two figures, and there is at this point the mark of a railing which

met that of the porch from the west. The fine lines which adorn the

bases of the engaged columns of the western wall and the course of

stone immediately beneath them are not continued south of the north

side of the southern column.

The presumption is, therefore,

that the comparatively unornamented space between these two points was

not ordinarily visible. (See Plate II.) This is another argument for

the existence of a building in this corner. The wall between these two

points cannot well have been an interior wall, for it has all the main

lines of the (p.226) other parts of the external wall. Any building

which stood in the corner would probably have been low, with a railing

around its roof which hid the western wall of the Erechtheion at least

to the height of the railing of the porch of the Kopa. The platform

formed by this roof with its railing would naturally be accessible from

the interior of the small building. The south-west corner of the

Erechtheion is called in, the inscription: (C.I.G. 160, C.I.A.

I, 322, § 2) ἡ apc πρὸς τοῦ Κεκροπίου, the corner by the Kekropion. We

may then safely affirm that the low building in the corner was the

Kekropion.

From the great pier which terminates the northern

wall of the Erechtheion at the south-west corner of the north porch

(Pl.I, E), a wall ran toward the west or south-west, which probably

turned toward the south, and met the southern terrace at some distance

west of the Erechtheion. The enclosure thus formed was entered from the

north through the small door S, which leads from the porch through the

northern wall just outside of the western wall. The lower part of the

pier which terminates the northern wall is not finished in a line

parallel to the length of the building, but slants toward the terrace,

and it is clearly to be seen that a double wall met the building here

(Pl.II, h and h'). Fergusson thinks that this enclosed a covered

passage,

being led to this opinion by the flat stone which covers the small door

by the pier. But as nothing positive is known of any buildings in this

direction, and as a covered passage can be accounted for only by

supposing it to lead to some building, the assumption involves us in

too many complicated hypotheses. We can confidently assert only the

existence of a wall at this place ; and the small door leading from

this great porch justifies us in assuming that this wall belonged to an

enclosure or τέμενος, to which the door formed the entrance.

In

the second step of the stereobate, under the great pier just mentioned,

and in a stone now lying near it, are the remains of an ancient drain

discovered by Botticher in 1862, the purpose of which has always been

more or less enigmatical. The direction of the drain is from the corner

by the porch of the Kopa. This corner was, as we have seen, probably

occupied by a building, the water from the roof of which must have run

off into the enclosed court-yard west of the Erechtheion. The drain was

probably intended merely to carry off this rain-water.

Footnotes:

1. See Plate I. (2), A and b, b.

2. Plate III and IVm g; Plate I, m,m,m

3. Apoll., III. 14, 1, 2: ἀνέφηνε θάλασσαν, ἣν viv Ἐρεχθηίδα καλοῦσι. See Paus I, 26, 5

4. See Pl. IV., ε,ε; and Fig. 1, p. 223. The two rectangular

holes in the first and third courses are, as their workmanship show, of

late origin.

5.Pl.III, v

6. Pl. I, B

7. Pl. III, p,o; Pl. IV, m,n.

[Return to table of contents]

|

|