|

The Age of the Old Parthenon

(Article originally published in 1902 in the journal Communications of the German Royal Archaeological Institute, vol. 27 [Ath.Mitt.XXVII] , pp. 379-xxx)

Ten

years ago I published in this journal (1892, p.158) an article on the

"Older Parthenon," the temple discovered under the Parthenon of

Pericles by L. Ross during his excavations on the Acropolis in 1835.

Among other things, I tried to prove that this temple was not the old

Hekatompedos destroyed by the Persians, as was previously generally

believed, but a much larger temple that had only been built after the

Persian wars. The older view had formed at a time when the "older

Athena temple" further north was not yet known and therefore the "older

Parthenon" had to be regarded as the only larger pre-Persian temple.

The message from Hesych about an older temple burned by the Persians

(s. v. "hekatompedos neos") could only be related to the remains lying

under the Parthenon. Thinking of an older Erechtheum was out of the

question because of the large size of 100 feet

But two facts

remained unexplained in the older view. First, according to Hesych, the

burnt temple was supposed to be fifty feet shorter than the Periclesian

structure; but in fact the older Parthenon surpassed the younger temple

by several yards. Secondly, the column drums built into the north wall

of the Acropolis, which were attributed to ancient Hekatompedos, were

made of marble and were unfinished, while the pieces of entablature

built further west, which were also attributed to him, belonged to a

finished and already painted poros building.

An attempt was made

to remove the first objection by adding a smaller temple corresponding

to Hesych's dimensions (p.380) to the large substructure with excellent

foundations; so lastly F. C. Penrose in the Journal of Hellenic Studies

1891, 275. However, in that article I could assert against this that

the protruding part of the substructure, if it had not had anything to

support it, could not possibly have been founded to a depth of 10 m.

The excellent foundation, made of regular blocks, must have supported

the columns or walls of the temple itself, as the surviving remains of

the steps directly prove. Also the proposal by L. Ross [Arch. Essays

I 138), explaining the eastern part of the substructure for a later

addition and thus raising the difficulty is untenable. The whole

substructure is actually built in one go.

The second objection,

relating to the difference in material and work, was attempted to be

countered by the assumption that the temple provided with poros steps

had a poros entablature, but exceptionally had columns of marble, and

that, moreover, only the columns and steps were still unfinished. But

even these assumptions could be described as very questionable.

It

was only when a second ancient temple was discovered between the

Parthenon and the Erechtheion in 1885 that both concerns were

eliminated. This temple, which certainly dates from pre-Persian times,

was apparently the Hekatompedos burned by the Persians. First of all,

it corresponded to Hesych's indication of a size difference of 50 feet

between the older and younger Hekatompedos. Without its ring hall, the

"old Athena temple" was a hekatompedon: pronaos, naos and opisthodome

together formed a 100-foot structure, a "hieron hekatombpedon". In the

younger Parthenon, on the other hand, the east cella alone had a length

of 100 feet and was therefore a "neos hekatompedos". But a west cella

of about 50 feet was added to her. The Temple of Pericles could

therefore be rightly said to be 50 feet larger than the pre-Persian

100-foot structure. Second, the dimensions of the finished Porous

entablatures made them an excellent match for the foundations of the

ancient Temple of Athena, while the unfinished marble columns (p.381)

probably belonged to the unfinished older Parthenon. Both attributions

were fully confirmed when the still missing column drums and capitals

made of this material came to light in the northern castle wall below

the entablature of Pores (cf. Middleton Plans and Drawings of Athenian Buildings, Pl. 6), and when also below the marble drums the same steps of limestone found on the older Parthenon have been identified.

This

established that before the time of Pericles there had been two great

temples of Athena on the Acropolis: the "older Parthenon" on the site

of the present Parthenon and the "old Athena-temple" south of the

Erechtheion. But were they both pre-Persian?

Since Hesych only

speaks of a single pre-Persian temple of Athena, the Hekatompedos

burned by the Persians, since our second temple, the older Parthenon,

was demonstrably never completed and never even got beyond the

substructure and the lowest column drums, everyone decided who have

been writing about the temples of the Acropolis since 1885, for

assuming that the older Parthenon was only begun after the Persian wars

and, after a shorter or longer interruption, was only completed by

Pericles. As far as I can see, only F.C. Penrose, in the essay cited

above, maintained that the older Parthenon was pre-Persian. However,

its dating, about a century before the Persian Wars (Journal of Hellenic Studies 1891, 295), could be described as completely impossible.

It

is therefore now accepted that the older Parthenon was built between

479 and 447 BC. Opinions only differ about the exact time when

construction began. Having myself espoused the older time of Kimon [Ath. Mitt. 1892, 188), A. Furtwangler suggested Themistokles as the builder (Meisterwerke p. 164), while F. Kopp (Yearbook of the Inst. 1891, 270) of the more recent time of Kimon and finally B. Keil (Anonymous Argent. p. 98) prior to the Eurymedon battle.

However,

recent studies of the older Parthenon itself and of the (p.382)

retaining walls erected on its south side have convinced me that all

these dates are incorrect. The older Parthenon is pre-Persian. When the

Persians destroyed the castle, it was in the middle of its

construction. Its scaffolding was set on fire by the barbarians. From

479 to 447 BC, i.e. for a generation, the burned substructure of the

temple that had been started could be seen next to the temporarily

restored "old Athena temple". Only Pericles rebuilt the "great temple"

according to a slightly different plan.

I.

Before presenting

the evidence for this thesis, I must make some corrections and

additions to my earlier essay about the ruin itself.

I had

previously left it undecided whether the base of the temple had two or

three steps (Athens Mitt. 1892, 187). There must have been three. In

addition to the two lower steps that are still in place, several step

stones have been found under the pillars of the northern Acropolis

wall, which have similar dimensions and the same characteristic profile

as the middle step of the substructure. Its material (Kara limestone)

is harder than the limestone of the two lower stages. A fragment of the

same harder stage is built into the S.W. corner of the Younger

Parthenon as an underlay of the southern stylobate (see fig.1 below,

where the profile behind Marble Stage 3 is indicated).

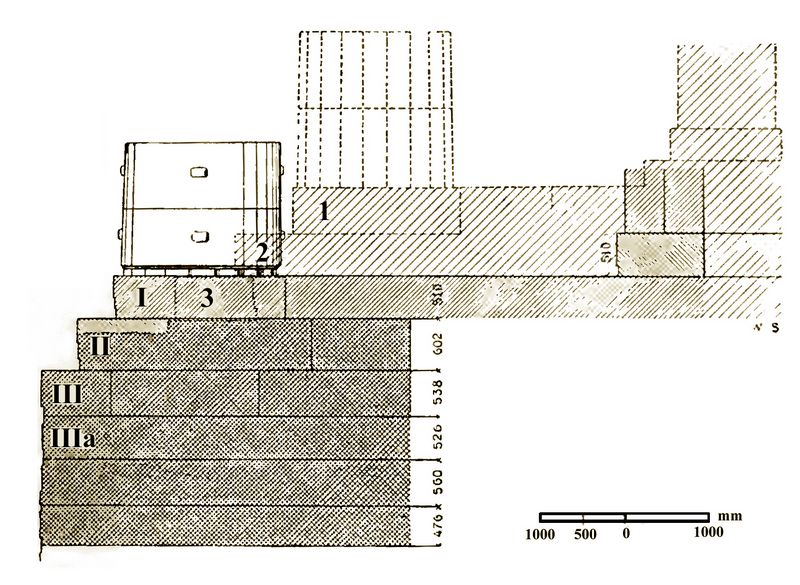

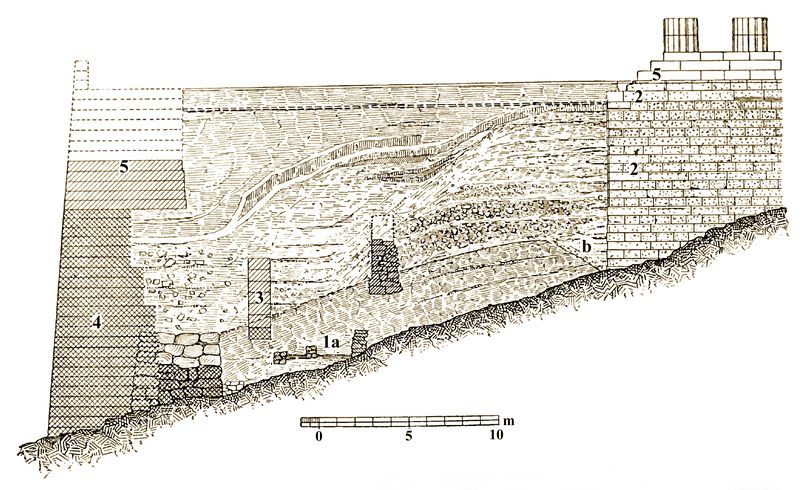

Fig.1: Cross-section of the step building of the older and the younger Parthenon.

The

steps of hard stone formed the stylobate of the ring hall. The

allocation is confirmed by the stone lengths: while the lower tier

consists of stretchers of 1.70-1.80 m, the second tier is formed by

trusses that are only about half the width (0.90-1.00 m) and have a

very great, but different depth (in the east 1.59-2.32 m). Because of

the latter fact alone, a stylobate of stones of even depth must have

lain above it, the length of which in turn has to correspond to the

runners of the lower level. In fact, the existing hard limestones not

only have these (p.383) dimensions, but also agree with the previously

inexplicable marks found on the substructure, from which I already

suspected in my earlier essay [Ath. Mitt.

1892, 186]. Stones of this form had closed. We can now even determine

the exact location of the joints of the stylobate on the south side of

the temple from the marks, although very few of the stones themselves

remain.

The shape of the step structure as it now appears is shown in fig.1 in section. The in situ

stones of the older temple are double hatched, the added steps of the

same hatched. The stones of the younger temple have received an even

lighter hatching. The older stages are denoted by the numbers I. II.

III, the younger ones by 1. 2. 3. The level originally designated as

the lower level of the old temple, which later became Euthynteria, has

received the designation IIIa.

Accordingly, if the temple had

three steps, the length of the stylobate is calculated as 75.06 m and

its width as (p.384) 29.60 m. Since the corresponding dimensions of the

younger Parthenon are 69.51 m and 30.86 m , the older temple in the

stylobate was 5.55 m longer but 1.26 m narrower than the younger

building. The number of columns, as I had previously ascertained, was 8

on the short sides and 19 on the long sides. The axis width of the

columns is calculated to be equal for both sides at about 4.12 m, a

coincidence that can be regarded as valuable confirmation of the

correctness of the entire calculation. A difference in the size of the

ax widths on the short and long sides, as it occurs in several older

temples and thus also in the ring hall of the "old Athenian temple",

does not exist in the older Parthenon.

The ground plan of the

inner temple can be drawn in the way I have explained earlier [op.cit.

p.177), with the younger walls and rows of columns, taking into account

the displacement of the temple axis, not exactly, but in general. As a

result of the addition of the third step, the older foundations now

apply a little better than was the case with my earlier drawing [op.

cit. p. 177), together with the younger walls and rows of columns. The

floor plan that was added hereafter is shown in fig. 6 (see below). The

thickness of the cella wall is assumed to be about 1 m according to

several marble blocks built together with the column drums. With regard

to the design of the pronaos and the back hall, one can hesitate as to

whether 6 Doric or 4 Ionic columns are to be assumed. In the ground

plan drawing, I opted for the former because the column drums with a

diameter of 1.90 m also have several smaller Doric drums with a

diameter of 1.72 m Diuxhmcsser that only cover the top or bottom stone

of the Column shaft may have formed. Since a lower diameter of 1.90 m

has an upper diameter of less than 1.72 m, the smaller drums must be

assigned to the anteroom and rear hall. They are too big for the inner

columns of the cella. Ad. Michaelis [Arx Athens.Plate. VIII) only drew

(p.385) 4 columns in his addition to the temple floor plan in the

vestibule and thus decided in favor of the second possibility. Since

there are objections to both solutions, a third possibility must be

considered: the porches could contain only 5 pillars; the column drums

with a diameter of 1.72 m would then fit better because of their

strength. But such an unusual arrangement seems to me very little to

recommend. A 1.95 m drum built into the north wall must be counted

among the corner pillars of the ring hall, since the corner pillars on

the younger Parthenon are also somewhat stronger than the remaining

pillars.

II.

The terraces heaped up to the south of the

temple, with their retaining walls and masses of rubble, are of greater

importance to the history of the Parthenon than has been attributed to

them up to now. Usually only two walls of this kind are mentioned, a

polygonal lining wall of irregular limestone, running almost parallel

to the south side of the temple at a distance of 10-13 m, and the

Cimonian castle wall, which is considerably stronger and higher and

about twice the distance from the Temple has (both walls at Middleton op.cit.

pl.2). In reality, however, there is a third retaining wall that lies

between the two in terms of time and space. Opposite the two corners of

the temple it is built of regular blocks of porosity. No new wall was

built between them, but the old Pelasgian castle wall was used as a

lining wall for the masses of rubble and was probably raised a little.

In a report published during the excavations (Ath.Mitt. 1888 p. 434), my then relative dating of these periods was correct, but the absolute one, as will be shown later, was wrong.

In

order to understand the various epochs of temple construction and their

dating, a precise consideration of the individual supporting walls and

their backfillings is urgently required (p.386); it is still possible

on the basis of the numerous photographs which were taken during the

excavations for the collection of the German Institute and copies of

which can be obtained from the Institute. (The catalog is published in Arch. Anzeiger from 1891 p. 75 and 1895 p. 55

In

these images, which are unmistakable witnesses to the stratification

and composition of the rubble, the various retaining walls and rubble

masses that gradually formed south of the Parthenon can be examined and

identified in detail. One can clearly see how behind the various walls

several layers of dark earth alternate with those of broken building

elements and sculptures, and how lighter stripes stand out in between,

consisting of small stone chips (rubble) of limestone or marble.

One of those pictures that I have previously published (Ath.Mitt. 892

Taf. IX), may first be described here (plate 9). It shows the layers of

earth between the Parthenon and the polygonal retaining wall. Above the

bedrock we can see the foundation of the Parthenon on the right, and

various superimposed layers of earth and stones on the left. The old

layer of humus, which is supported by the Pelasgian castle wall further

to the left and which is not visible in the picture, reaches up to the

3rd block layer of the foundation and up to the head of the man

standing there. It has covered the rock since very ancient times and

its surface indicates the height of the terrain before the beginning of

the temple construction. All items it contained (including some

red-figure sherds) must predate the temple.

At the beginning

of construction, a pit was cut into this layer of humus, reaching down

to the rock, which was filled with rubble again after laying the lower

layers of blocks. The pit appears in several photographs (e.g. in the

picture Acropolis No. 74) as a lighter triangle next to the temple

foundation. In our picture, the line of demarcation is somewhat

obscured by the man. A thin layer of small boulders follows above the

humus layer, the surface of which stands out as a lighter line (p.387)

and extends to the middle of the 4th cuboid layer. The following layer

corresponds to the height of two cuboids and contains many fragments of

broken poros buildings. Its surface, in turn formed by lighter building

splinters, stands out strongly. In the vicinity of the foundation,

instead of the larger pieces of foros, there are heavier masses of

building rubble. Above this follows a layer corresponding to three

layers of cuboids, which in its lowest part contains some lumps of

porosity and then masses of earth mixed with small stones. Its upper

limit is formed by a double light line at the level of the 9th cuboid

layer. Two stone layers higher, you can see another light layer of

building rubble in the darker masses of earth. Traces of another bright

layer can be seen at the level of the 13th block layer.

L. Ross

and others have already correctly recognized that these light-colored

layers of building rubble arose from the fact that the stone splinters

that fell off when processing the blocks were spread out on the

respective terrace to secure the piled-up masses of earth (cf. also Ath.Mitt.

1892 p .162). In addition to the long, light lines running through the

entire terrace, one notices in the picture near the base of the temple

still shorter lines and thicker layers of light-colored rubble. Their

origin is due to the fact that the entire surface of the substructure

was cleaned of building splinters after the completion of each block

layer. After they had been swept down from the wall, the latter formed

larger or smaller heaps, some of which remained lying next to the

substructure and others were spread out over the terrace. Only after

the completion of each 2 or 3 layers of ashlars was the entire terrace

and its supporting wall leveled out evenly.

Another important

fact can be seen in our picture (plate 9). While the masses of rubble,

reaching up to 9 blocks, are held together by a polygonal retaining

wall, the remains of which lie to the left under the rubble, without

being visible in the picture, next to the higher horizontal layers of

earth, reaching up to 14 blocks, we see several obliquely sloping

layers of Earth and (p.388) small stones, also crossed by a few thin

light lines. These sloping strata extend beyond the polygonal retaining

wall and appear to belong to a period when the backfill already reached

beyond this retaining wall to a second wall. The old Pelasgian castle

wall opposite the center of the temple served as such, which was

probably raised a little at that time. Opposite the two ends of the

temple, however, are the already mentioned walls of porosity blocks,

which we shall later learn more about.

The mound around the

temple does not appear to have reached higher than the 15th block

layer, because firstly, the above-mentioned marks are located on the

16th layer, which were made when the stylobates were made, and

secondly, the ergasterion (building hut ), of which a stone is just

visible in our picture above left. An even higher deposit around the

temple was only possible when a stronger and higher retaining wall for

the masses of earth was created by the Cimonian castle wall. These

upper layers of earth, which are missing in our picture, were already

removed by L. Ross during the excavations of the 1830's. The

description by L. Ross [Arch. Onto.

I p. 104) is sufficient. In it he found splinters of porous and marble

(i.e. building rubble, "latupe") mixed with head-sized stones blown off

the living rock of the Acropolis. It is obviously rubble that was

spread out at the time of the construction of the Parthenon in

Pericles. When Ross adds that those head-sized pieces of rock were

blasted off the Acropolis rock when the temple foundations were laid,

he is wrong, because the pieces of rock would then have to be found in

the lowest layers of rubble. Rather, they were only blasted off the

rock when, after the completion of the Periclean Parthenon, the plateau

east and north-east of it was created by working down the rock. The

fact that a 1.15 m and originally even 1.70 m (p.389) lower level

around the temple was planned for the older Parthenon and therefore the

rock was to be worked down even deeper earlier leaves no doubt about

this that the blasting off can only have taken place under Pericles. So

it was only then that the last heaping up of earth took place on the

south side of the Parthenon. The upper part of the southern castle wall

may have been built at the same time as the last elevation, while Kimon

certainly built the lower part. I am therefore referring to the lower,

larger part of the south wall in the passage in Aeschylus' pleading for

protection (v. 134), to which Bücheler (Rhein. puree XL 629) pointed out.

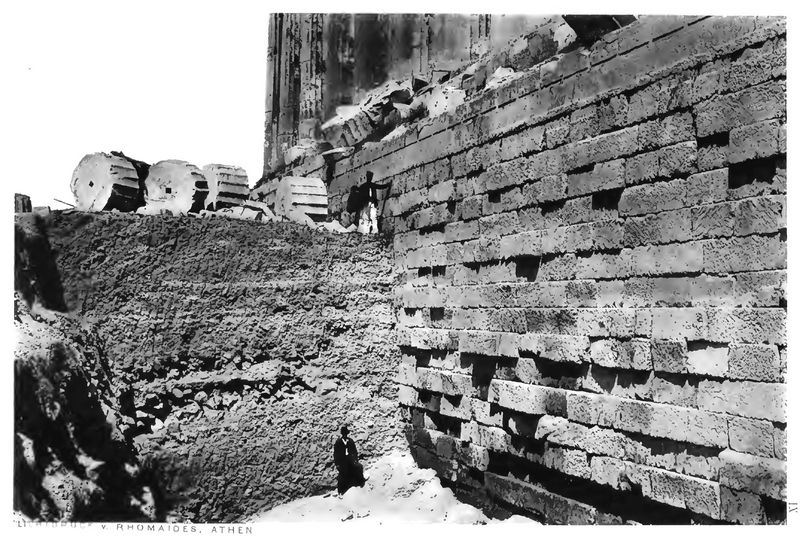

A

second photograph reproduced in the accompanying Plate XIII (Acropolis

No. 81) gives a more comprehensive view of the different periods of the

deposits. On the right we can again see the substructure of the

Parthenon, the lower blocks of which are still covered by the earth.

Next to it lie the almost horizontal layers of porosity fragments and

earth that we are already familiar with, again interspersed with thin

and thick layers of light-colored rubble. Here, too, the gradual growth

of the terrace can be followed step by step. In the two lower visible

layers, many fragments of poros buildings, broken into manageable

pieces, are used for filling, in the upper layers only earth and small

stone chips. From the polygonal retaining wall, which holds these

masses of rubble together, only a few upper stones can be seen in the

middle of the picture, their lower part is still in the ground. Above

this wall and further to the right we note the sloping strata of earth

formed as the upper plateau widened. They are not as strong here as in

other photographs, and moreover seem to be somewhat disturbed in their

upper part by the east wall of the ergasterion, which is founded on

column drums and ashlars. This building hut will only date from the

time of Pericles, because it requires the presence of the Cimonian wall

visible on the left edge of the picture and the Periclean wall in its

upper part. The horizontal layers below the (p.390) column drums,

criss-crossed by lines of light-colored building rubble, might

initially be taken for the backfilling of the Cimonian wall and

therefore dated to the time when this wall was built, but a closer

study of the layers and the ground plan soon convinces us that the

right half of this rubble, composed of horizontal strata (from the

polygonal wall to the first two workers), is still of the third period,

and was once supported by the now absent structure of the Pelasgian

wall. The appearance of the layers of rubble corresponds to that of the

higher layers next to the temple. On the other hand, only the masses of

rubble lying further to the left, which clearly show a different

composition in the photograph, belong to the construction of the Kimon

wall. Only this last rubble is, as we shall see later, definitely the

real "Persian rubble"; all other layers of our picture date from

pre-Persian times.

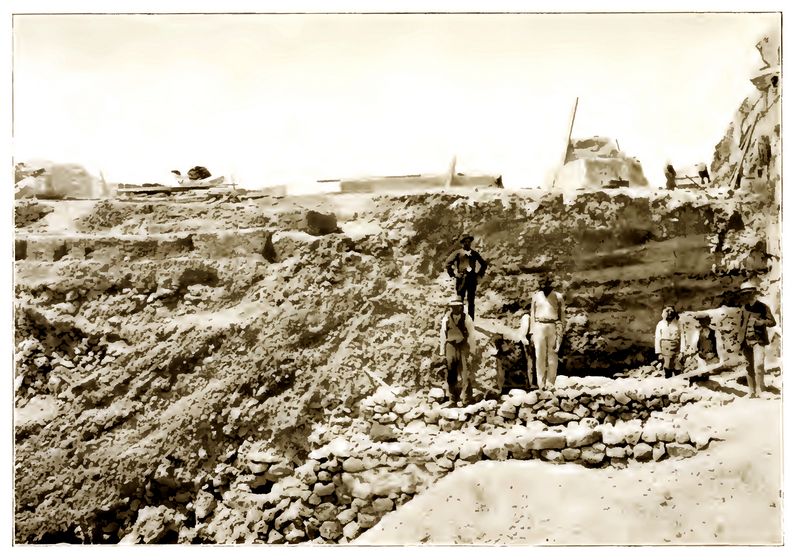

We publish a third picture on

Plate XIV (Acropolis No. 91). It shows a profile of the strata slightly

to the west of the previous photograph, adjacent to one of the two

inner walls of the Ergasterion. Little can be seen of the Parthenon's

substructure. The adjoining layers of earth of the same age as it, on

the other hand, are clearly visible. The obliquely sloping layers,

which were only small in the previous picture, are particularly strong

here. They can be traced to the lower edge of the picture and

apparently already extend beyond the line of the polygonal retaining

wall, which is not visible. Above them lies a layer of ashlars from the

foundation of the inner wall of the ergasterion. On the left edge below

this wall, the remains of layers of rubble can still be seen, which do

not yet belong to the Kimonian wall but, like those sloping layers of

rubble, belong to the second construction period of the temple. Younger

layers of earth and debris masses are not shown in the picture.

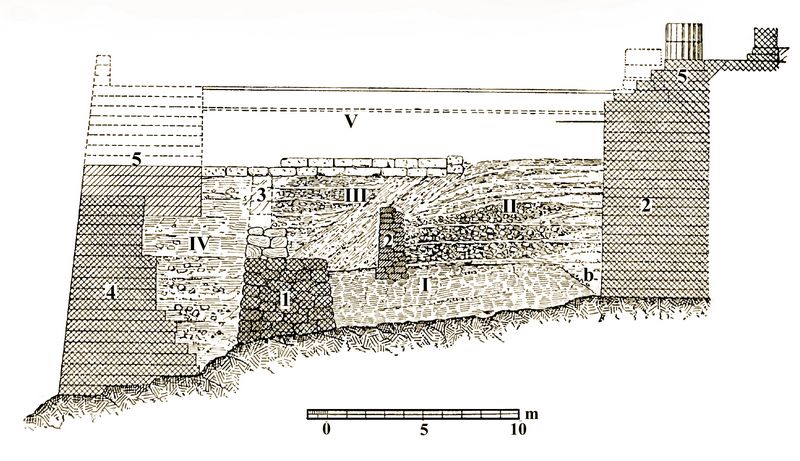

On

the basis of these various photographs and sketches that Georg Kawerau

made during the excavations and kindly made available to me, I have

compiled the two sections shown in figs.2 and 3. They are intended to

show the facts next to the southeast corner (p.391) of the temple and

adjacent to its western half. In order to better illustrate the gradual

formation and composition of the various terraces, I had to piece

together the facts of several photographs taken at different locations.

Fig.2:

Section t

In

Fig. 2 on the right the substructure of the older Parthenon (2) with

the steps of the younger building (5) is drawn in section. The steps of

the older temple, insofar as they were later removed, and two

unfinished pillar drums are indicated by dotted lines. Follow the rock

on which the temple rests to the left under the Kimonian castle wall

(4). Below the temple, the rock line rises to the right, only below the

temple wall will it be worked horizontally a bit. Since the strength of

this wall is not known, I drew the line of the rock completely

horizontally. Before the construction of the temple began, only the

Pelasgian wall 1 and the associated layer of earth I lay above the

rock. The building pit described above, which was cut into this oldest

layer of humus, bears the letter b. The accumulation of layers of earth

and the associated polygonal retaining wall 2 kept step with the growth

of the temple substructure. When the substructure rose above the

12-layer course of ashlars, it was found that the retaining wall was

not sufficient, and so the sloping masses of rubble soon began to fall

over the wall, especially as it could not be raised because of its

thinness. The heaps of rubble gradually covered the polygonal wall 2

and in part reached as far as the Pelasgian castle wall 1. Opposite the

center of the temple, this probably received a superstructure made of

ashlars (3), of which, however, nothing has survived. Opposite the

corners of the temple, however, special ashlar walls were erected from

Pores. Its location, which can be seen in the ground plan in Fig. 5,

and its shape can only be discussed after this ground plan. How the

structure of the Pelasgian wall was designed cannot be said with

certainty, because not only its later structure but also its old top is

so badly destroyed that we can no longer even determine the original

shape and height (p.392) of the wall know. That the structure, as shown

in the drawing, consisted of regular ashlars, I infer from the

circumstance that the two walls opposite the corners of the temple are

built in this way. The backfilling of these ashlar walls was again done

in horizontal layers of stones and earth, between which lighter lines

of rubble can be seen. The sloping heaps reaching over the polygonal

wall and those horizontal layers together form the second building

period. On average they are marked III.

But even by this measure

the terrace could scarcely be brought to the height intended for the

older temple, which is marked in our section by two dotted lines. The

fact that it actually did not reach this height at that time can be

seen from the level of the ergasterion, whose floor can probably be

assumed to be at the height of the second layer of ashlars of its

foundation. In order to make the terrace even higher, a new strong

retaining wall had to be built further south. The southern castle wall

(4) served as such, which according to reliable literary tradition was

built by Kimon (Paus. I 28, 3; Plut. Kimon 13). Simultaneously with it,

the horizontal strata of rubble rose, which are marked IV on our

section and consist of real "Persian rubble," i. H. of rubble

containing numerous structures and sculptures burned and smashed by the

Persians.

Somewhat later, when Pericles raised the level around

the temple when building the temple again, more rubble had to be spread

around the temple and the Kimonian wall had to be raised even more. The

upper part of the wall erected at that time, which is significantly

wider than the Kimonian wall, I have designated 5 and the terrace

behind it V. As the rubble of the latter was removed by Ross as early

as 1835 and drawings or photographs of them do not exist, I have left

the upper part of the terrace white. The drawing published by Ross

[Arch. Essays I, Taf. V) gives a (p.395) further eastern section and is

therefore used as valuable material in the other profile.

Fig.3:

Section t

The

second section (fig.3) lies in the extension of the eastern front of

the temple and is intended to show not only the retaining walls shown

in fig.2 but also the retaining wall made of porous blocks (3)

belonging to the second period of temple construction. I owe the height

figures of this drawing to Georg Kawerau. I took the shape of the earth

masses from various institute photographs (e.g. Acropolis Nos. 74, 85,

86, 87, 114, 116, 119, 121) and the sketches by Kawerau and Ross. The

substructure of the Parthenon is not drawn in section, but viewed from

the east (cf. the photographs of the Acropolis, Nos. 4-9). The teaching

edge at the corner only starts at the 9th layer from the bottom (at c).

The originally intended height of the floor next to the temple is

indicated by a single line, as in Fig. 2, the height of the floor

intended later when the steps of the older Parthenon were made by a

double dotted line, the height actually achieved after the completion

of the younger Parthenon by two full ones lines indicated. The various

retaining walls have been given the same numbers as on the other

intersections. The remains of an ancient dwelling house la can be seen

within the oldest layer of humus, the floor and remains of the wall of

which had already been buried when the temple was built. The triangular

building pit b for the temple has been cut into the same layer of

humus. The polygonal wall (2) is lower than in fig. 2 because the

terrace it supports slopes towards the east (cf. the photograph of the

Acropolis, no. 87, which shows the facade and the foundations of the

wall). Sloping layers of debris that had fallen over them are here of

very little thickness.

The retaining wall of the second

construction period (3), made of porous ashlars, is only secured by one

stone in the line of our average. However, since it is better preserved

farther east (cf. the photographs of the Acropolis, Nos. 65-67), it was

allowed to be added to the drawing. We do not know its former height.

Only a few stones (p.396) are preserved here from the Pelasgian wall

(1); it was partially broken off during the construction of the strong

Cimonian wall. In the absence of drawings, the backfilling of the

latter could only be indicated schematically. For the uppermost layers

of earth of our section, which may be called the backfill of the

Perikleisian wall 5, I have used the drawing by L. Ross (Arch. Essays

I Taf. V) as a basis. Particularly characteristic of the rubble masses

of this youngest part of the terrace is the stripe of white marble

splinters left light in the drawing, which arose during the processing

of the marble blocks of the temple.

[Return to table of contents]

|

|