|

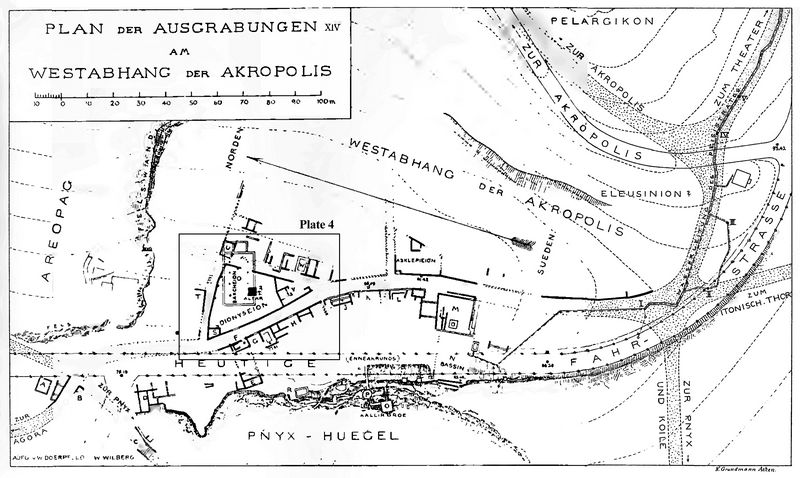

Excavations on the west slope of the Acropolis.

II. The Lenaion or Dionysion in the Limnai (part 1)

Article originally published in 1895 in the journal Mittheilunger des Kaiserlich Deutschen Archaeologisch Instituts, Band XX, pp. 161-205 (Communications of the German Imperial Archaeological Institute, Athenian Section, vol. 20, abbreviated as Athens Mitth. XX).

Plate 4: Plan of structures in the sanctuary of Dionysius Lenaios.

Now that a general overview of the results of the excavations up to the end of 1894 has been given in Report I (Athens Mitth. XIX p. 496), we here begin the detailed discussion of the uncovered sanctuaries, buildings and water systems with a sanctuary, the Dionysion in the Limnai.

whose uncovering and investigation is fully completed, and which

can claim to be one of the oldest and most important sanctuaries in

Athens.

A part of the district was found in the beginning of

1894 and soon recognized as the long-sought Hieron of Dionysos Lenaios.

The whole sanctuary with its temple, its altar and its wine press was

only excavated in October and November of the same year. In the Roman

period it was completely ruined and overbuilt by a structure which,

according to an inscription found in it, was the meeting house of the

association of lobakchen and was called Baccheion.

We shall first discuss the older ruins, then the younger ones, and finally try to establish the name of the sanctuary.

A. The ruins of the ancient sanctuary.

The

general location of the sacred area in the valley between the

Acropolis, Areopagus and Pnyx is described earlier and can therefore be

assumed to be known (cf. plate 14 of the previous volume). The district

forms a triangle in plan, which was surrounded on all sides by public

roads. The base line, located on the driveway to the Acropolis,

measures about 45m, the greatest height about 25m, so that the total

area of the district is about 560 square meters.

Plate 14: Map of survey region, showing location of sanctuary of Dionysius Lenaios (inset for plate 4).

The structures

that have been uncovered are drawn in different colors and in different

ways on plate 4, depending on their age. They belong in the main to

three periods: 1. The Greek, whose ruins are laid out on the plan with

solid black paint or with black hatching; 2. the early Roman, whose

walls are hatched in red; 3. the late Roman ones, the remains of which

have acquired a full red hue. The ancient streets are again entirely

dotted, as in the earlier plan, and are therefore easy to survey.

Today's driveway is made recognizable by small circles at the lower

edge of the plan, which are intended to indicate the trees. In order to

distinguish the water pipes for fresh water from the numerous canals

for rainwater and house water, those are drawn black and blue, the

latter only black. The drinking water fountains are also colored blue

in the fountains, while the access boxes of the canals are only

indicated by a black circle. For external reasons, the orientation of

the whole plan was chosen in the same way as on plate 14. North is on

the left, east at the top. The inscribed numbers indicate the height

above sea level in metres.

The buildings of the different

periods can be distinguished on the spot with complete certainty, first

by their material and construction, and then by their altitude. In

fact, the ancient Greek structures consist either of hard blue

limestones assembled in a polygonal construction, or of ashlars of

Piraeus limestone (porous); of the more recent buildings, only the

foundations, made of small stones and clay, have survived; the most

recent ones use different kinds of stones (p.163), mostly bonded with

lime mortar. Equally clear is the difference in height of the three

building complexes one above the other. While the floor of the old

district is about 77.25 m above sea level, the floor of the youngest

building, the Baccheion, shows the figure of 79.60 m. The old district

was buried more than 2m high in Roman times, so that the lobakehen, if

they held their meetings in the Bakeheion

in the IInd or IIIrd Century AD, could no longer see that, deep under

their meeting house, was an old sanctuary of Dionysus. How high the

burial had risen by early Roman times. cannot be determined precisely

because the floor of the middle building cannot be seen. It seems to

have been almost as high as in the 3rd period.

We owe the relatively good state of preservation of the

oldest buildings to the low location of the old district and its high

level of burial. They are so well preserved that there is no doubt

about the identification of the individual features of this sanctuary

or hieron, a building with a winepress in the north corner, a small

temple in the south corner and some insignificant assets.

Fig.1: Section of the south end of the western perimeter wall.

The

perimeter wall of the precinct is a retaining wall on almost all sides,

because the interior of the sanctuary was in most places lower than the

outer streets. The difference in height was originally up to 2m and

increased as the roads gradually rose. Only on the north-west corner

was the interior of the district slightly higher than the street. The

wall is built of polygonal blue limestone throughout its length, but is

not of the same construction throughout. In fig.1 a piece of the

southern end of the exterior of the western wall is shown. At

the bottom one sees large, carefully joined polygonal stones; above

that is a fairly good polygonal masonry made of small stones, and at

the top is a piece of poor masonry made of small (p.164) stones, which

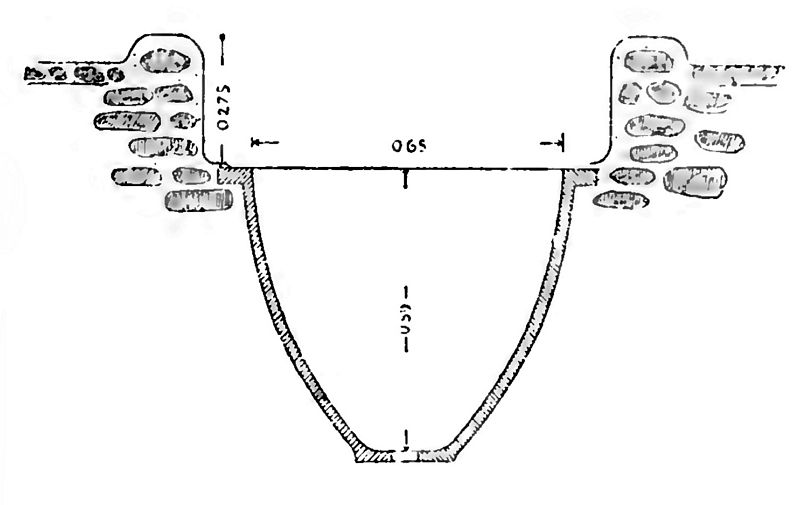

must be of a later date. fig.2 shows a piece from the north end of the

same wall, belonging to the west wall of the winepress.

Fig.2: Section of the north end of the western perimeter wall, adjacent to the winepress.

It

differs from the wall shown in fig 1 mainly in that the stones of the

lowest layer are not polygonal, but are cut entirely at right angles.

In the other parts, namely in the north wall and in the middle of the

west wall, there are large and small stones next to each other on the

inside, which gives the building a very ancient appearance. One almost

believes one is looking at a wall of the so-called Mycenaean (p.165)

period if one looks at the wall section shown in fig.3 from the inside

of the north wall. The processing and joining of the stones is not very

careful.

In my opinion, this disparity in the masonry in the

individual parts of the district wall can only be explained by the

assumption of multiple alterations, which have taken place over the

course of the centuries-long existence of the district. A very extensive repair is to be observed in the central and

southern parts of the eastern wall; you can still see a piece of the

older, good enclosing wall and behind it a younger wall made of

different materials. In the plan (on plate 4) the latter is hatched in

black and red at the same time, because it cannot be decided whether it

still belongs to the old Greek district or whether it has to be

ascribed to the older Roman reconstruction.

Fig.3: Section of the inside of the north perimenter wall.

On

the eastern and northern sides of the district, where the enclosing

wall had to withstand a strong ground thrust due to the difference in

ground level, it was supported by buttresses, some of which are still

intact, others only in small remains. Only one seems to have existed in

ancient Greek times; the others, because of their poor construction,

must be ascribed to the period shortly before the old sanctuary was

buried.

No remains have been found of a larger gate building.

Since there is also no trace of a simple gate (p.166) in the course of

the outer wall, we have to look more closely at the gaps in the wall

that now exist to see whether there could have been a gate at one of

them. On plate 14 of the previous year, a gap in the western boundary

wall south of the wine press is drawn and an entrance gate assumed to

be there. The height conditions spoke in favor of this, because the

interior of the district and the street were at the same height here.

However, the recent deeper excavation of the street has shown that the

lowest layer of the wall is still well preserved here and next to it

are the old curbstones, which served to protect the wall against the

passing carriages. A gateway can therefore hardly have lain here. Since

there is no gap suitable for a gate in the north wall either, the

entrance gate at the southern end of the east wall, where the only

large gap is found, must be completed. This place is particularly well

suited for a gate, because the temple faces it with its vestibule, and

because the square in front of the temple is at the same level as the

two streets that meet here. If one had entered the forecourt of the

temple, one could go down to the sacred precinct through the door,

still well preserved, at the north-west corner of the temple. This

seems to have been the only access to the Hieron.

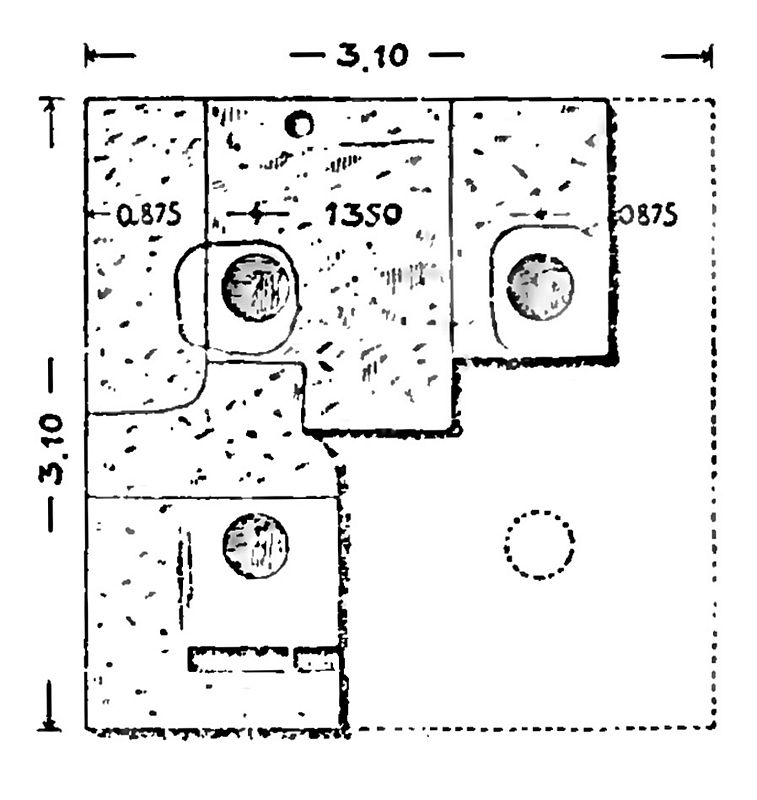

Most of the

substructure of the large altar in the middle of the district, which is

in the form of a table, has been preserved. The stones found, which are

shown in the ground plan below (fig.4), are sufficient to draw the plan

of the entire altar with complete certainty. The substructure assembled

from porous limestone blocks formed a square with a side length of 3.10

m and had four holes, each 0.24 m in diameter and 0.10 m deep, which

once held four small columns as the feet of a table. If, as we may

assume, the cover plate to be added protrudes about 0.20 m over the

feet on all sides, we get a square of about 2.00 m for this plate. At a

later

Fig.4: Ground plan of altar.

An

initially very inconspicuous indentation on the substructure offers a

very special interest. In fact, on the western step one notices an

elongated hole 0.49 m long, 0.13 m wide and 0.08 m deep and next to it

the rest of a second similar hole, the other half of which disappeared

with the neighboring block. Anyone who has ever seen the numerous

examples of the inscription stones serving as documents on the

Acropolis of Athens or in other sacred areas cannot doubt for a moment

that those two holes were also used to accommodate stone steles. One of

these steles is, as will be shown later, known from Demosthenes

(Apollodor).

But may we also safely describe the above-mentioned

substructure as the remains of an altar? I do not wish (p.168) to

emphasize that no other acceptable explanation has yet been proposed,

but rather to point out the fact that altars in table form appear on

vase paintings, particularly for Dionysus. The cover plate of a 2.3 m

long and 1 m wide sacrificial table dedicated to Dionusos Auloneus was

also found in Attica (Athens Mitth.V,.

p.116). Finally, a lower stone with 2 round holes very similar to our

structure has been preserved in Eleusis (cf. O. Rubensohn, The Mystery Sanctuaries in Eleusis and Samothrace,

p.196). Its addition to an altar is secured by the inscription, some of

which has been preserved. The explanation of our substructure as an

altar is therefore not subject to any reservations.

We are unable to determine the exact age of the altar. Only so much can be said

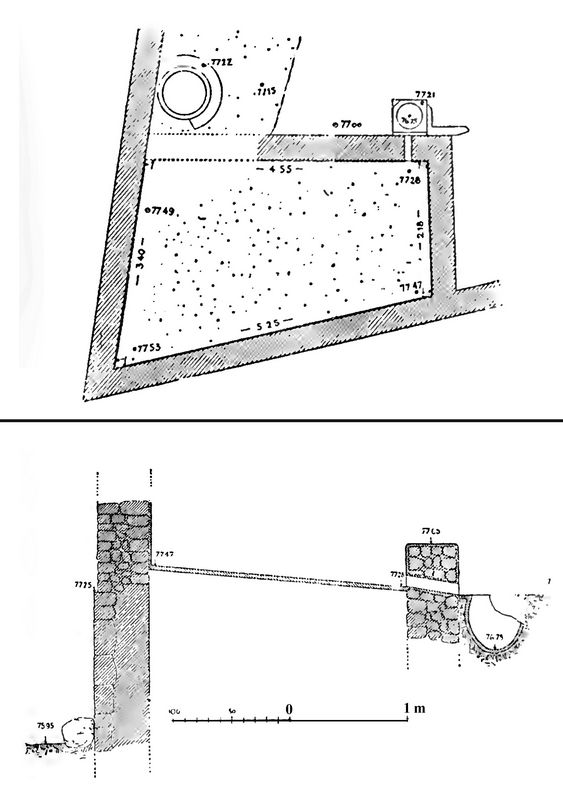

Fig.5 (top): Ground plan of winepress.

Fig.6 (bottom): Section of wine press.

The

building preserved in the north-west corner of the district is

inconspicuous at first, which only has a few thin walls and floors made

of pebble screed, and yet it is not only very valuable in and of

itself, but also of almost inestimable importance for the determination

and naming of the district. The best-preserved room in this building is

in fact a Greek wine press, and the other rooms must also have been

used for wine-making. The ground plan of the winepress (cf. fig.5.6)

forms a somewhat irregular square with an average length of 4.70 m and

a width of 2.80 m. Its interior shows a well-worked screed of river

pebbles and lime mortar, which is not horizontal, but has a steep fall

of 0.25m towards its south-east corner. The east wall is drilled

through next to the deepest point of the floor and in front of the

opening there is still a round thong vessel with a square upper rim and

an inner diameter of 0.50 m and a capacity of around 55 litres. Its

shape can be seen in the (p.169) adjacent cross section through the

wine press (fig 6). Next to the vessel there is a small square

depression made of mortar, the shape and meaning of which can no longer

be recognized because of the severe destruction. While the northern and

western walls of the wine press served at the same time as the border

wall of the district and as (p.170) enclosing walls of the building to

which the wine press belonged, perhaps also carried a roof, the eastern

wall was only 0.35 m high and is still visible today their surface a

plastering with rounded corners, such as is still customary for

practical reasons on such low walls. The height of the southern wall is

not known.

The fact that the room was not a water tank can be

concluded with certainty from the large slope of the floor and the low

height of the east wall. For the same reasons, a living space is also

out of the question. The facility was undoubtedly a wine press. Wine

presses are still made in a very similar way in many areas of Greece

today. A square, paved square is surrounded by low walls, the floor is

given a steep slope, the outer wall is pierced at the lowest point, and

a small brick, stone, or clay vessel is placed in front of the hole so

that the grape juice can pour from the stepping stone into this vessel

run and can be scooped there.

Wine presses were also made in the

same way in the Byzantine period, as evidenced by the numerous wine

presses found in Olympia, which belong to the Vth and VIth centuries

AD. It is well known that grapes were trampled in cellars in antiquity

as well, and this is shown on vase pictures. I owe K. Buresch the

reference to the large presses in the Dionysian procession of Ptolemy

Philadelphia (in Athenaios V 199 a), and to the krathres upolhveos in the inscription of the king of Commagene in Humann-Puchstein, Reisen in Nord-Syrien

p. 215 Z. 25. That clay vessel located near the wine press may then be

called wol krathr upolhnios. With the wonderful tenacity with which the

Greek farmer now holds on to his plow and other agricultural

implements, which were common thousands of years ago, it is not

surprising that the design and equipment of the wine press has not

undergone any significant changes from ancient times to the present day.

{p.171)

To the east of the winepress is a second one, with a room with a

similar floor covering of pebbles, which unfortunately is so badly

damaged that not even its extent can be determined with certainty. Its

purpose is also unknown, although a

Fig.7: Vessel embedded in floor of second winepress room..

A

third narrower chamber, which contained a gully, is connected to the

south of the winepress. Its floor is destroyed. Next to it is a 1.0 m

deep, brick and plastered container. which was probably connected to a

water pipe and may have served to store the water needed for winemaking.

For

determining the time of the cellar system, it is important that the

front wall of the Lesche, located on the road just opposite the wine

press, shows a very similar design with small stones and also has the

same altitude. Since the Lesche has to be placed in the fourth century

(p.172) on the basis of the found boundary stones with the inscription

HOROSLESCHE, we can also attribute the wine press to about the same age.

At

a later time, a piece of the winepress was cut off, and still later a

completely new, smaller winepress was built on top of the older one

(cf. Plate 4). This occupies a little over a third of the older site

and has a limestone and small pebble soil that slopes to the east. The

vessel that once held the must from the younger wine press no longer

exists. Higher still we found a wall belonging to the Roman house of

the lobakchen, which proves that even the younger press was no longer

visible at the time of the Roman Baccheion. The fountain that occupies

the northern corner of the cellars also dates from this late period, if

not from the Middle Ages. Since some remains of an even older floor

have been found below the Greek wine press, and since the outer wall

also shows an older construction in its lower parts, we are justified

in assuming that a wine press has existed here since Archaic times.

Unfortunately, the remains cannot be determined in more detail without

partially destroying the upper wine press.

[Continue to part 2]

[Return to table of contents]

|

|