|

Excavations between the Areopagus and Pynx hills.

(Originally published in 1891-2 in Communications of the German Imperial Archaeological Institute, Athenian Section [Ath.Mitt.] vol. XVI, pp. 443-445, and vol. XVII, pp.90-93 and 439-445)

1. Finds (1891, pp. 443-445)

The

German Archaeological Institute began excavations in Athens at the end

of January [1891], with the aim of trying to find any of the buildings

mentioned by Pausanias on the Athenian Agora. It was first to be built

to the east of the so-called Thieseion and to the north of the new

railway, at a point where, according to Pausanias, the Stoa Basileios

must have been located. However, since the owners of the plots of land

located there have not yet granted (p.444) permission to carry out

excavations, the spade has been used temporarily at a different location

If

one climbs up to the Acropolis on the modern road between Areopagus and

Pnyx, one sees an old water pipe driven through the rock on the right,

which apparently led drinking water to the vicinity of the Areopagus,

i.e. to the old market place. This line was taken as the starting point

of the excavations. On the one hand, the upper course and the origin of

the line should be determined and on the other hand, a water tank and

running well should be sought at its end point. Since Pausanias now

names a fountain in the market place or at least in its vicinity,

namely the famous Enneakrunos, there is the possibility of bringing the

much disputed question about the location of this largest and most

important fountain of the city closer to a decision.

The first

part of the task has already been partially solved. On the left side of

the modern driveway, the upper continuation of the rock line was found

and cleared. It consists of a walk-in canal built from large blocks of

limestone and covered with similar stones. Its direction clearly shows

that it comes from the upper Ilisos valley and runs along the southern

slope of the Acropolis. A rock canal located deep under the Hofgarten

and still carrying plenty of water, which E. Ziller (Ath.Mitt.II p. 112) has already described in detail, can be connected with this pipeline without any hesitation.

The

construction of the newly uncovered section of the pipeline best

confirms the previous assumption that it was a Greek and not a Roman

water pipeline; its size is also a sure sign that in Greek times it was

the main supply pipeline for fresh water for the city.

At the

current end of the line, between Pnyx and (p.445) Areopagus,

excavations have been started, which, however, have not yet brought to

light a running well. But an ancient road, supported by a lining wall

of large stones, has come to light, which led from the area of the old

market in an arc to the Acropolis, its gradient ratio (about 1:20) is

just as great as it is for one is appropriate for such a rise and is

required by the special floor design. Beside the road (to the north)

was a Roman or Byzantine cistern with a clay pipe, and below it a Greek

or Roman building, the floor of which is a marble mosaic. Three Roman

marble heads and a statuette of Hecate came to light as individual

finds.

Between the old road and the end of the rock conduit,

where, judging by the height of the latter, the well might very well

lie, the excavations have not yet penetrated down to the ancient soil.

So there is still hope of finding the ancient fountain here. However,

should nothing of the same be found—so be it. because it is completely

destroyed, or because it lies further to the north or west—then the

discovery of the old road and the Greek aqueduct has already provided a

new and secure basis for the topographical investigations into the

Athens market. [W. D]

2. Finds (1892, pp.90-93)

The excavations

in Athens undertaken by the German Archaeological Institute, about

which I reported in these communications (Att.Mitt. vol. XVI, p. 443), continued

during the months of February and March [1892], but were then

interrupted as a result of the Institute's travels. Their purpose, to

bring clarifications about the most important questions of Athenian

topography and especially about the location of the city well, has not

yet been fully achieved, and the excavations will therefore be resumed

and completed in the course of the summer. A detailed report on the

results obtained and a location plan of the uncovered buildings will

only be published after the excavations are completed; I confine myself

here to a brief listing of the results obtained after my last report.

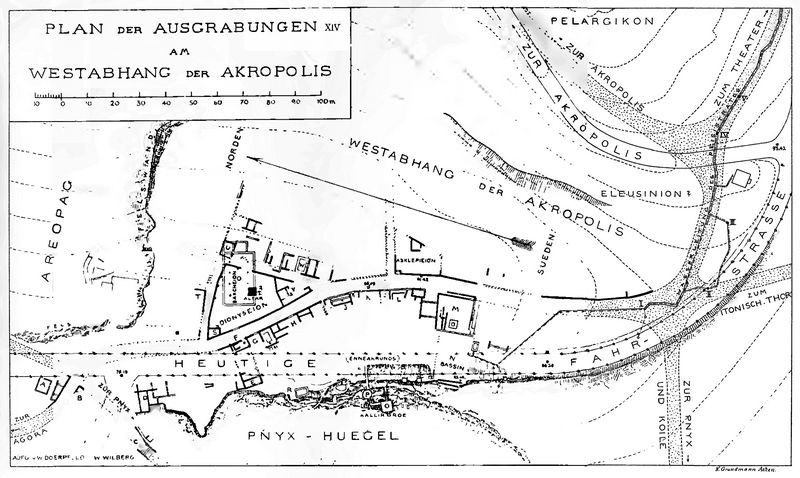

Fig.1: Area of excavations, 1892-1893 (from Plate XIV, Att.Mitt.XIX [1894]).

The

ancient road found between the Areopagus and Pnyx (p.91) has come to

light for a large stretch farther south. It first crosses today's road

and then gradually climbs up to the east next to it to the Acropolis.

Originally surrounded by polygonal walls, over the centuries it has

increased so significantly that those walls later disappeared under the

floor. Beneath the road is a high drainage canal made of hammered clay,

to which manholes lead down at several points. Of elliptical

cross-section, it was excellently suited for the drainage of all bodies

of water and in fact alone on the stretch we uncovered it contains 13

side canals, which lead to it water from all sides.

On the west

side of the road, between it and the great Greek aqueduct running along

the Pnyx rock, several buildings have been uncovered which, according

to their construction and on the basis of preserved inscriptions, may

be dated to the fifth and sixth centuries BC. Walking up the road, one

first encounters on the right a small sanctuary, surrounded by

polygonal walls, containing two boundary stones with the sixth-century

inscription HOROS: one of the stones is still in its old place. In the

small precinct one notices a chapel-like temple without pillars, in

front of which stands a round altar made of porous. It is not known

which god or hero was worshiped here. The material and technology of

the small temple point to the sixth century as the time of edification.

As early as the next century, the sanctuary was buried under the ground

as a result of its deep location in relation to the gradually higher

path, because in the fourth century there is already another building

above it, which was marked by two boundary stones on the road that were

still in their old place, with the inscription HOROS LESCHAE being

confirmed as Lesche.

On the street above the Lesche there is a

small building, also made of polygonal limestone (p.92), on the outside

of which two inscriptions from the fourth century [BC] are carved,

which indicate that the house was encumbered with several mortgages, so

it was probably a private house.

Further up, on the same western

side of the street, are the remains of a building, carefully erected in

a polygonal style, in which one must recognize a large water reservoir,

because of its interior decoration and its numerous outflows. Its date

of construction is the fifth or sixth century [BC]. Initially we

believed that the reservoir itself formed part of the city well being

sought, but further discovery showed that this was probably not the

case: it may only have been an elevated reservoir above or a basin

below the fountain.

So far nothing has been found of the city

well itself; but that it must have been in the vicinity of the

excavation site, certain indications are the large number of existing

water pipes, then the fact that the large Greek water pipe preserved on

the Pnyx rock seems to end right here and finally the discovery of a

natural spring with a rock gallery between the tank and the large rock

aqueduct. Unfortunately, the point between this spring and the

container could not be completely uncovered because it is covered by

the current road.

I shall not mention here the other

installations, which have come to light in particular on the other side

of the old road. because their basic plan and meaning have not yet been

fully ascertained. In any case, it is certain that the excavations have

brought us close to a place where, in ancient times, there was a

natural spring, probably with a simple fountain: in the same place, in

early Greek times, there is a large aqueduct from the upper Hissos -

Thale, apparently to bring more water to the well, which was no longer

sufficient for the city's needs.

Since now, on the basis of the

reports of Thucydides, Pausanias and others, the main well of Athens,

the so-called Enneakrunos, must have been located below the Eleusinion

on the festive road, which led up from the market to the Acropolis, and

since it, originally a simple structure called Kallirroe, enlarged by

Peisistratos and certainly made into a nine-mouthed fountain by adding

new water, I myself no longer have the slightest scruples about

supposing the Enneakrunos to be at the place we excavated, especially

since they also come from other places. For reasons which this is not

the place to discuss, this very spot of the ancient city for which

Enneakrunos must be claimed.

However, this is only my personal

belief so far. The well itself has not yet been found, and therefore

anyone who thinks he must move the Enneakrunos to another part of the

city is not yet forced by the results of the excavations to give up his

opinion without further ado. We hope from the continuation of the

excavations that even the last doubts will be lifted and that some find

will show with certainty whether the Enneakrunos was located near the

market place where Pausanias places it in his description of Athens, or

whether those who are looking for this fountain at the opposite end of

the city next to the Olympieion on Hissos are right.

3. The Excavations at the Ennearkrunos (1892, pp.439-445)

After

the excavations that the German Archaeological Institute conducted last

year in Athens between Areopagus and Pnyx (cf. above p. 90) have come

to a preliminary conclusion with the discovery of the well complex I

was looking for, I am publishing a short communication here about the

results achieved. A detailed report will appear in one of the next

issues of this journal once the necessary plans and drawings have been

completed.

The old road, which led from the Agora to the west

around the Areopagus up to the Acropolis, has now been determined to be

about 220m long. Several footpaths branch off from it, some of which

lead to the people's meeting place on the Pnyx, some to the main

entrance gate of the Acropolis; they could not be used for wagons

because of their gradients.

On the western side of the street,

that is between it and the Pnyx rock, several Greek private houses have

been discovered in addition to the sanctuary with temple and altar

already described, two of which, according to the inscriptions that

have been preserved, were mortgaged. Across them, between the street on

the one hand and the Areopagus and the Acropolis on the other, there

seem to have been no dwellings, but only sacred precincts, because the

walls uncovered there have a different character than on the opposite

side; they are enclosing and retaining walls, but not house walls.

In

the most northerly district adjoining the Areopagus, which in antiquity

lay lower than the road, I presume was the Dionysion sanctuary in the

swamps; one in the middle we may call Asklepieion, according to the

finds made therein; the southernmost district at the western foot of

the Acropolis, which is surrounded on three sides by the [p.410]

ancient road in an arc, can hardly be anything other than the

Eleusinion.

Only a larger piece of the Asklepieion has been

excavated, with the remains of a marble table in a small chapel, in

addition to the enclosing wall and the entrance gate. several votive

offerings and a large number of foundation stones for stelae and other

votive offerings came to light. The reliefs are votive offerings of the

most diverse forms for healing that has taken place; one of them, on

which a female breast is depicted, bears a dedicatory inscription to

Asklepios.

Since most of the foundation stones and also the

lower part of the marble table decorated with two snakes were found in

their original place, the assumption that the reliefs were all carried

here from the large Asklepieion next to the theater is completely

inadmissible. Next to the small chapel, the mouth of a well has come to

light, which presumably belongs to the well that formed the center of

the cult and contained the healing water. Since the district seems to

be older than the introduction of the Asklepioscultes in Athens,

another healing deity must have been worshiped in it originally

Just

opposite the Asklepieion and in the axis of the Propylaea of the

Acropolis, at the foot of the Pnyx rock, a large fountain has come to

light, in which we may recognize the Enneakrunos, the city fountain of

Athens.

Excavations have shown that just below the People's

Assembly Square, several natural springs emerged from the Pnyx rock. In

order to increase its water and use it for daily use, the water veins

have been followed through tunnels deep into the rocks and several rock

chambers have been created and set up as water tanks. Seven such rock

canals and six water reservoirs of various shapes have so far been

found. Today, these tunnels no longer supply water; but that such

occurred in antiquity [p.441] is proved by the gullies made of clay,

which still lie in and in front of some of them. The

fountain-like vessels, on the other hand, still contain some water. In

the present state of the surface of the Pnyx and Museion hills, one

should not expect any more rich springs at their foot, since the

rainwater runs off easily in all directions and therefore does not

penetrate the ground.

That even in ancient times the water from

the Pnyx springs was sometimes scarce is shown on the one hand by the

laborious rock formations and on the other hand by several deep wells

which have come to light on the spot in front of the rock face, where

we can imagine the oldest well house, and in part still do deliver

water. Even when the springs had almost completely dried up in

midsummer, water could still be drawn from these wells. The

probable often recurring water shortage had to increase the more the

city grew. Nothing could be done with new tunnels and basins. A

thorough remedy was needed. We owe it to Peisistratos, who in the 6th

century conducted copious amounts of water from the upper Ilisso valley

to the old fountain site by means of a magnificent rock pipe.

This

aqueduct, which runs deep under the Court Garden and under the southern

slope of the Acropolis, was already described in the previous volume of

these communications (Ath.Mitt.

XVI, p. 444). Its northern end, which served as the starting point for

our excavations, has turned out to be a Roman-era extension of the

Greek pipeline. The real end of the line was a mighty water reservoir,

which was placed directly above the old well square. Its original size

can no longer be determined exactly; later, after reconstruction, it

covered an area of around 250 square meters, so it was just as large as

the basin of the stately Hadrianic aqueduct at the foot of Lycabettus.

The

place where the pipe emerged from the Acropolis rock has not yet been

determined: it will be one of the tasks (p.442) for the intended

continuation of the excavations. The piece of pipe found between the

Acropolis and the large basin consists of large blocks of porosity,

which formed a walkable underground channel. Two old clay pipes, which

are of special value for the dating of the whole complex, proceed from

the latter. One, which has an inner diameter of 0.19-0.22 m, conducted

the water underground to the large basin; the other, only 0.12-0.14

strong, the end of which has not yet been revealed, seems to have

brought water to the Asklepieion. The individual tube pieces are

0.60 to 0.61 long (not including the beginning of the interlocking) and

consist of a finely ground organic clay. Inside they are covered with

red varnish, outside they have no coating, but only two strips of the

same varnish at both ends and in the middle. Joined together by a cast

of lead, the tubes formed a very tight duct, the cleaning of which was

made possible by the fact that each tube had an elliptical opening

closed with a special cap. These pipes agree in a striking way with the

clay pipes of the famous water pipe, which Polycrates of Samos had

built by Eupalinos of Megara in the 6th century. As far as one can

judge from the description and illustration given by E. Fabricius (Ath. Mitt.

IX p. 175), the tubes appear to be almost identical. I hope to be able

to make a direct comparison soon. Even now there is no reason to doubt

that the clay pipes (and with them the whole system) are ancient Greek

products because of their varnish, the way the individual pipes are

interlocked, and the way they are sealed with lead (fig.3).

Fig.3: Section of clay pipe from Greek pipeline uncovered during excavations [source: Tagebuch der Ausgrabungen 2, p.26 (Daybook of excavations, Areopag., Acropolis and Pynx, 2nd period. 1 Nov 1892- 10 Feb.1893, p.26)]

In order to

locate the old well house, we uncovered the space between the basin and

the old road. The well house itself did not come to light, but several

stones did, which demonstrably belonged to the well house (p.443) of

Peisistratos. As the terrain conditions indicate, this must be set

north of the large basin directly on the Pnyx rock, i.e. at the same

place where the oldest well construction with the natural springs was.

Since the site is just below the current road, which is planted with

trees, only minor excavations could be carried out, which have not yet

yielded a reliable result. It will later have to be excavated next to

today's road and the whole area up to the ancient road will have to be

uncovered. However, we should not expect to find much of the old well

construction after it has been established from the stones of the well

house that were built into a Roman house that at least part of the

facility was later destroyed. But we may hope for further confirming

discoveries, which, in view of the importance of the question to be

decided here, will be welcome to everyone.

The stones of the

well house are partly large blocks of porous limestone, one of which

contains water channels with two mouths and is covered with lime

sinter, as it is still formed in the Athenian water pipes today, partly

from blocks of limestone mined at the foot of the Hymettos near the

village of Kara, which to the stylobates and the lower parts of the

buildings of the 6th century is regularly used. One of the latter

ashlars seems to have belonged to the floor of the fountain ball, while

the other, because of its shape and its washes, probably belonged to

the structure serving as a water channel, which is attached to antique

illustrations of the fountain house below the mouths. Moreover, on this

stone there is precisely that bracket form (Z) which is observed in the

oldest Athenian buildings.

Yet another finding fitted very well

with this determination of the date of the great aqueduct. Two shaft

wells were found between the basins in the Pnyx rock and the ancient

road, which were filled in at the latest in the third century BC

(p.434). They were filled to the brim with rubble containing hundreds

of pottery sherds, exclusively pottery of the Geometric and other

related styles. Black-figure, red-figure or other sherds of recent

times did not occur. If, therefore, the filling took place no later

than the 6th century, it can be linked to the change in water

conditions caused by the construction of the Peisistratic aqueduct.

After good and plentiful drinking water had been channeled from the

Hymettos or Pentelikon to the Agora, the old uncomfortable deep wells

could be filled up.

Thus, finds of the most diverse kinds unite

to the important result that in the oldest times there was a city

fountain consisting of several springs and Tiel fountains on the road

between the Agora and the Acropolis, namely at the foot of the Pnyx,

and that this was the case in the 6th century when a large one was

built The aqueduct coming from the upper Ilisso valley was enlarged and

became a sight of Athens because of its abundance of water, so we must

recognize the famous Enneakrunos in this fountain system on the basis

of the reports of the old writers. This is not the place to go

into literary matters; this is to be done in one of the next

issues of the Communications.

It may only be indicated here for those who have a special interest in

the question that, in my opinion, Thucydides could only be called as a

witness for the situation of the Enneakrunos on the Ilissos because his

statement (11, 15) was misinterpreted. With "touto to meros tes poleo"

he does not describe the part of the old town at the southern foot of

the Acropolis, but that part of the city of his time that was the

oldest city and was officially called "polis" at that time, i.e. the

whole the upper Acropolis and part of the old town at its southern (and

southwestern) foot. Towards this old town, i.e. in front of its gate

(p.435) opposite the Areopagus lay not only the old sanctuaries

specifically mentioned by Thucydides, but also the city well, formerly

called Kalirroe, later called Enneakrunos.

Fig.5: View of a cremation grave in the Eleusinion on the north slope of the Areopagus (photo date: Dec.1892)

In the

planned continuation of the excavations, the correctness of the naming

of our well as Enneakrunos can easily be tested. Above the Enneakrunos,

Pausanias saw the Eleusinion, and after the market, that is, below, a

theater called the Odeion. Both systems must be able to be activated.

The Eleusinion must have been situated on the western slopes of the

Acropolis, south of the discovered small Asklepieion and on the spot

where the three tombs are found. The Odeon, on the other hand, must be

on the west side of the Areopagus. Its search is easily possible and

must lead to the goal soon, since the discovery of a round wall or step

is enough to recognize the building as a theatre.

The less the

location of the found fountain fits the picture which most of the

experts have formed of ancient Athens, the more it is obligatory to

continue the excavations. Reliable results will not fail.

WILHELM DORPFELD.

[Return to table of contents]

|

|