|

THE EARLIER PARTHENON

(Article originally published in 1892 in the journal Communications of the German Royal Archaeological Institute, vol. 17, pp. 158-167)

Fig.1a: Photo of Parthenon, taken in 1862 by Francis Bedford.

(p.158) Ever

since L. Ross had the substructure of the Parthenon uncovered in 1835,

it has rightly been accepted as an established fact that beneath the

Pericles structure (fig.1a) lies the massive foundation of an

older temple, which Pericles used as the substructure for his great

temple to Athena. This older building has often been dealt with in more

or less detail, for example by L. Ross (Arch. Essays I p. 88), F. C. Penrose [Principles of Athenian architecture [1] p. 73 and [2] p. 98), J. H. Strack (The pre-Periclean Parthenon; Arch. Zeitung 1862 p. 241), E. Ziller (Zeitschrift für Bauwesen 1865 p. 39) and A. Michaelis (The Parthenon p. 119).

The

temple was unanimously held to be a large peripteros, to which the

numerous Doric building elements built into the northern castle wall

belonged, and it was believed to be the old pre-Persian Hekatompedos of

which Hesych (s. v. Hekktompedos) speaks. Opinions differed only with

regard to size. Some deduced the size of the temple from the dimensions

of the substructure and therefore considered it to be a larger

structure than the Parthenon of Pericles, while others took the view

that there was only a small temple in the middle of the large

substructure, that of a broad one surrounded by a stone terrace.

The

basis of these investigations changed completely when in 1885 the

ancient temple of Athena between (p.159)the Parthenon and the

Erechtheion was discovered and excavated in the following year. The

prevailing views, which speak of a pre-Persian or in general of an

older Athena temple, could no longer be related solely to the older

Parthenon, but should first be distributed to the two temples. But then

it had to be determined which of the two buildings was the older one,

and whether one of them came from post-Persian times.

I have

published detailed investigations into the ancient temple of Athena in

these communications (XI p. 337, XII p. 25 and 190, XV p. 420). At that

time I held out the prospect of a detailed treatment of the older

Parthenon as well, but I intended to publish it only when the exact

floor plans and sections of this temple and its surroundings, taken by

G. Kawerau during the last excavations, had been published. If I am

already going public with an essay on the older Parthenon, I am

prompted to do so by a paper by F C. Penrose recently published in the Journal of Hellenic Studies

1891 p. 275, which deals with the two older Athena temples.

This distinguished researcher is maintaining the view, first proposed

forty years ago, that a small temple originally stood on the large

substructure of the Parthenon, and that the Doric entablature pieces of

the northern castle wall are to be assigned to this building, again as

proven to be essentially correct (p.160). Earlier this view had been

refuted by A. Michaelis (Parthenon

p. 121) and others; that it is quite untenable even in the face of the

new discoveries, I hope to be able to show you below. However, I

will not confine myself to the negative work of refuting Penrose's

views, but will try to determine positively what the older Parthenon

looked like and when it was built.

In the past, it was only

possible to determine approximately how the mighty substructure of the

Parthenon is designed. One could only see its uppermost layers and

through a few holes, which were dug next to the substructure down to

the rock, one could determine the depth to which it reached down on the

four sides. Only through the excavations of the last decade, during

which the entire foundation was completely uncovered on all sides, have

its form and extent become better known. The description of the

substructure, which E. Ziller gave in the Zeitschrift für Bauwesen (1865 p. 39) on the basis of his measurements and subsequent excavations, has turned out to be completely correct.

The

photograph published on plate 9, which I took during the last

excavations, clearly shows the enormous size of the foundation and also

its processing in detail; on the right one can see the base of the

temple from the marble steps of the younger building down to the rock.

To the left, the layers of earth adjoin the substructure, which we will

discuss later. The place shown is approximately in the middle of the

southern long side. A section through the whole base, smaller sections

of the steps on the different sides of the temple, and a view of the

base on the western side are given in the text-figures of this essay.

As

I refer to Ziller's building description for all details, only a few

details necessary for understanding (p.161) what follows can be given

here.

The entire foundation is made of regular ashlars or square cut

stones of Piraeus limestone and reaches down everywhere to the bedrock,

which lies at a very great depth (up to more than 10 m) on the south

side, but forms the floor around the temple on the north side. In the

west and east the bedrock falls in stair-like steps down to its great

depth on the south side. In contrast to other buildings of the fifth

century, e.g. the Propylaea, the foundation material of which is

largely taken from older, pre-Persian buildings, only a few of the

Parthenon's foundation ashlars can be determined to come from

older buildings and to be here used for the second time.

Insofar

as Penrose denies this, he commits an error; even on our plate 9 you

can clearly see the old connection surface on a cuboid stone of the

fifth layer from below. Some of these stones can also be seen in

Ziiler's drawings (ibid.,

Plate B). The stones from older buildings were carefully worked into

rectangular blocks and were not built in their original state with

their various structures, as was customary somewhat later under

Pericles. However, by far the largest majority of the ashlars seems to

have been quarried in Piraeus specifically for the substructure of the

Parthenon and taken to Athens.

The construction of the high

substructure was carried out without any wooden scaffolding: one or two

layers of ashlar were shifted and then the surrounding area was raised

by adding earth or boulders by the appropriate amount. Instead of

scaffolding, the surface of the backfill then served as a building site

for the production of the next layers of blocks. The masses of earth

thus raised had to be supported with a temporary wall, which was raised

a little higher each time, and such was the polygonal retaining wall

which has been described in this journal (XIII p. 432), and (p.162) its

provisional character already apparent from its relatively low strength.

The

masses of earth between the lining wall and the temple foundation are,

as was the natural result of that type of construction, layered almost

completely horizontally and covered at certain intervals with thin

layers of light-colored rubble. The areas that appear as light lines on

our plate 9 are due to the processing of the porosity blocks for the

next layers. They have already been correctly recognized by Ross and

Ziller, and their importance for the chronological determination of the

substructure has been appreciated.

The manner in which the

construction and backfilling was done makes it beyond doubt that the

temple foundation, the earthworks and the polygonal lining wall were

all built at the same time. If one of these three parts can be

determined in time, then the age of all three is determined. Now the

age of the masses of rubble can indeed be determined from the objects

found in them. The numerous fragments of structural members and

sculptures made of porous limesone, which occur in the backfill and can

also be seen in our picture at the level of the fifth to seventh

layers, definitely belong to destroyed buildings. votive gifts and

other images. In addition to many sherds of black-figure and even older

vases, a large number of red-figure vase sherds were also found in the

earth masses. If the first finds indicate that the landfill took place

after the destruction of many ancient buildings and statues, the

fragments of red-figure vases show that this destruction took place at

the end of the sixth or beginning of the fifth century at the earliest.

It must therefore be regarded as a certain fact that we are dealing

here with so-called Persian rubble, and that the filling and thus also

the erection of the substructure took place in the first half of that

century.

The type of masonry (p.163) used for the temple

foundation also fits this position. Up to the end of the sixth century

in Athens, as far as we know, the foundations of the buildings were not

made of regular square blocks, but of more or less irregular blocks of

limestone. Only after the Persian wars was good ashlar masonry used for

foundations.

If Penrose nevertheless arrived at a completely

different dating, this was only possible through imprecise and

sometimes even wrong observations. According to his statements, first

the larger western part of the substructure should be erected using a

wooden scaffolding (p.291), then much later the masses of earth with

their wall lining were removed (p.289) and finally by partially

removing the masses of earth in the east again, the eastern part of the

foundation may have been added (p. 280). He puts the erection of the

first large substructure about a century before the Persian wars (p.

295). That this assumption and especially this dating is incorrect.

does not need to be further proved in detail based on the facts cited

above. It suffices to recall that Ross and Ziller correctly recognized

the evidence confirmed by the new excavations and presented them

essentially accurately. The high base was never exposed, but the

terrace covering it was made at the same time. Penrose must not have

recognized the thin, light-colored layers of limestone splinters, which

recur at fairly regular intervals, as building rubble, otherwise he

would not have been able to misjudge the facts.

A more

unfortunate oversight he represented in relation to the strata of earth

at the south-east corner of the substructure, the condition of which he

illustrates in a special drawing on page 281. The disturbance in the

even, almost horizontal progression of the layers, which could be seen

there, is supposed to be decisive evidence for the (p.164) supposed

later addition of a piece to the substructure. The change in the earth

layers at this point does not come from ancient times at all, but was

caused by a rectangular pit, which E. Ziller dug in 1864 to examine the

Parthenon foundations and later had it filled in again (a.a.0.p. 41 ).

Even

the small difference in the external arrangement of the blocks, with

which Penrose now, as before, tries to support his view of the later

addition of the eastern piece, must not be used as proof of this.

Because this deviation is limited, as Ziller rightly remarked, to a

single one of the many layers of ashlar and consists only in a small

difference in the work customs to be processed later. What the

foundation would have looked like if a piece had been added can be seen

at the north-west corner of the temple.

I have no hesitation,

therefore, in calling the relative as well as the absolute dating of

the substructure and its surroundings, as proposed by Penrose,

incorrect.

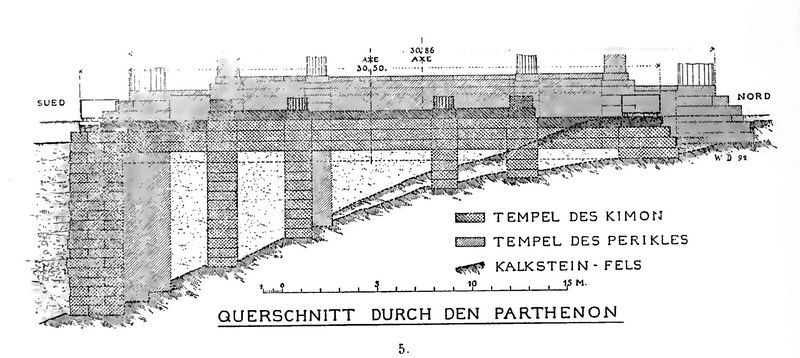

Fig.5:

Section through the southern wall of the Parthenon, showing the earlier

construction (Temple of Kimon) and the later temple, built under

Pericles.

In order to determine the extent and shape of the

older temple, we must first examine the four sides of the present

temple base. We begin with the south side, part of which can be seen in

the photograph (plate 9). I also give a section through the southern

wall down to the foundation in fig.5, which shows a cross-section

through the whole temple.

L. Ross, in uncovering the

substructure of the temple, had remarked that the upper strata are much

better worked than the lower ones, and that accordingly the former were

destined to be visible at all times, while the latter were to disappear

under the ground and serve as a foundation. In our photograph (plate 9)

you can see that the 15 lowest layers are not processed at all on their

outside; several cuboids, namely the trusses (p.165) even protrude a

considerable distance beyond the line of the wall; a minor editing can

be discovered only on the right part of the tenth shift. The first

quadrant, which shows continuous working, is the 16th, on the upper

edge of which a smooth strip the width of a hand has been made; here,

therefore, the encircling lines of the temple were untied for the first

time, and the overhanging pieces were worked off.

An even more

extensive smoothing is shown by the following 17th cuboid layer, a

stretcher layer which, apart from a narrow lower strip, is finished on

its entire outside. It can at most have been visible in its upper part;

in any case, the lower rough strip was underground. The 18th layer,

which consists of trusses, is fully worked out and each individual

cuboid is fitted with edge fittings and mirrors; it could already be

visible from the full height because of its good processing. From the

following layer, the 19th layer, only a few stones can be seen on the

left in the photograph, since they were damaged in antiquity or even

more recently by breaking out blocks.

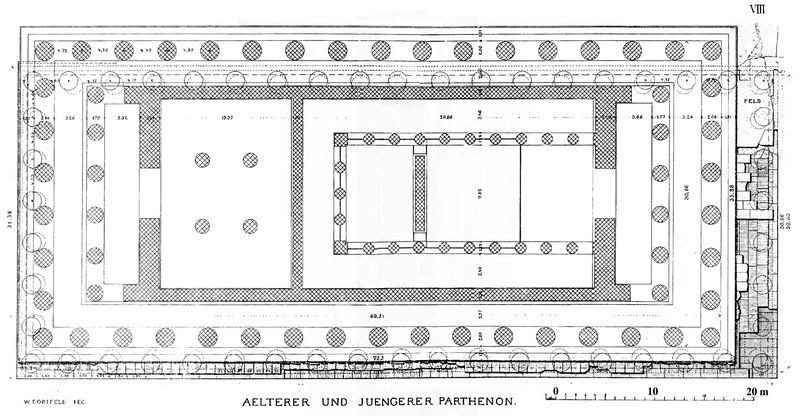

Plate 8:

Plan of the Parthenon in its current (Periclean) state. Traces

of the earlier construction are indicated by

faint circles for columns, and floor or stylobate stones below and

at far right..

Its front surface was

completely smoothed and has a hand-wide rim fitting on its lower edge.

In addition, it also shows processing on its upper side at a depth of

0.45 m, because the following, 20th layer recedes from it like a step

around this piece. The latter is also badly damaged; what is preserved

of it and the lower layer is clearly evident from the floor plan of the

temple on plate 8, which reflects the current state of the building.

There is therefore no doubt that the 19th and 20th layers, in terms of

their form and workmanship, were visible steps of the older temple. The

entire height of the lower stage has been preserved, while a piece of

the upper stage was chiseled off at the upper edge when the Pericles

Parthenon was built. The size of this piece can easily be seen from the

cross-section of the temple (fig.5) and from the section through the

eastern steps (fig.1).

[p.166) There is nothing in the building

itself of a further, third level, because immediately before the 20th

level the three levels of marble begin, which belong to the Temple of

Pericles. However, if the building used to have three levels, like most

later temples, one level is completely missing and we have to add an

upper level, the actual stylobate. But it is quite possible that the

older temple held only two levels, or more correctly a main level or

stylobate, and a lower level or euthynteria, as is the case with older

temples. This is known to occur, for example, in the case of the

Heraion in Olympia and the ancient temple of Athena on the Acropolis. I

believe that the latter case is present, that is, that the 20th cuboid

layer, which is still preserved in many places, was or should be the

stylobate of the temple itself. This assumption is based, on the one

hand, on the fact that the stones of this level are of very large

dimensions and penetrate the whole depth of the outer wall, which is

usually the case with the stylobate, but, as far as I know, never is

the case with the lower levels, and on the other hand, on the Presence

of vertical dowels on the bricks of the 20th layer, while there are

none on the 19th layer, as far as I have seen.

Fig.1: Section drawing of east side of the Parthenon showing steps.

On

the east side

of the temple the ancient substructure is of uneven depth; in the

southern half it has a total of 22 ashlar layers, while in the northern

part the bedrock reaches up to the level of the stylobate. Fig.1

gives a section taken about halfway down the east side. The

processing of the individual layers differs somewhat from that on the

south side, at least the upper layers show a different finish. The

uppermost layer, receding by one step width (p.167), which we assumed

to be the stylobate, is still processed in the same way as the

corresponding step on the south side, but the second from the top shows

a double work inch instead of the single work inch on the other side.

The third layer is designed even more differently, in that its blocks

have remained almost completely rough and only have a smooth upper

edge. The lower stone layers, as well as on the south side, have

remained unworked without exception. As for the third stratum from the

top of the south side, we could still doubt whether it was intended to

be visible; the east side reveals to us that it should be safely

underground.

[Return to table of contents]

|

|