|

The Chalcothek and the Ergane Temple.

(Article originally published in 1889 in Communications of the German Imperial Archaeological Institute, Athenian Department vol.XIV [Ath.Mitt, XIV], pp.304-313.)

The

southwestern part of the Acropolis between the Parthenon and the

Propylaea is divided into three terraces of different heights. The

easternmost, highest one belongs to the Parthenon, it is part of the

artificially prepared surface on which this temple rises as if on a

great base. Equally undisputed, the westernmost, lowest-lying terrace

forms the sacred precinct of Artemis Braunonia (fig.1)

On the

third, middle terrace, the temple and precinct of Athena Ergane was

generally attached. H. N. Ulrichs had first (Beisen und Forsch. IIS.

148) put forward the theory and tried to prove that Pausanias mentioned

a temple of Athena Ergane between the area of Artemis Brauronia and the

Parthenon, and that this building stood on the middle terrace

Only recently has this assumption been publicly questioned by G. Robert (Hermes ΧΧII p. 135) and by myself (Ath. Mitt.

XII p. 55). Robert and I try to explain the words of Pausanias (I 24,

3) in very different ways, but we agree that there was no special

ergane temple at all.

Numerous reasons can be given for this assumption. Some of these I have already briefly indicated (Ath. Mitt. XII). They may be detailed here:

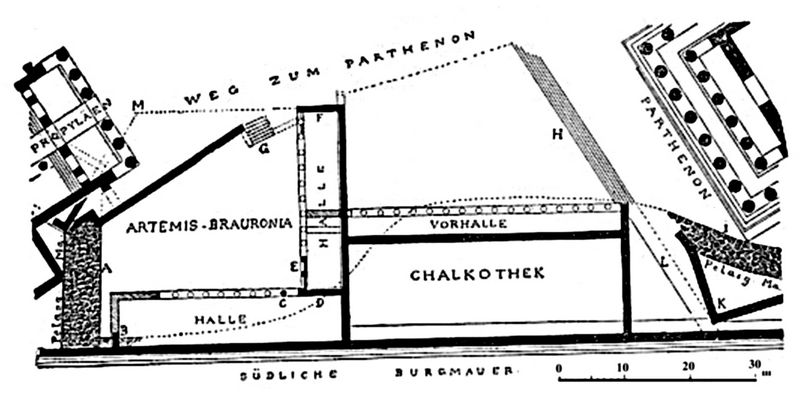

Fig.1: Map of Acropolis, showing location (arrow) of Chalcothek building (after Ath.Mitt. plate 14).

1.

No message from an ancient writer and no ancient inscription mentions

anything about an Ergane temple on the Acropolis. This fact in the

meaning given to Athena as Ergane, i.e. as goddess of handicraft and

artistic activity, in Athens, is evidently only to be explained if

there was no such temple.

2. A "τέmenος έργοpόνου Πaλλadος," not

a "νχός" of the same, is mentioned in an epitaph (p.305) in verse. The

same (C.I.A. III 1330) reads: "Eikona men graptan, oia pelei,

amripolooi thekamen ergoponou Pallados en temenei." Athena Polias was

not only the valiant owner and protector of the castle, but she herself

was also the goddess of crafts and arts. One was therefore probably

justified in poetically describing the Acropolis, the "hieron temenos"

of Polias, as the district of the working Pallas. In any case, this

expression justifies us in assuming a special temple of the ergans.

3.

Several inscriptions found on the Acropolis contain dedications to

Athena Ergane. The older ones are compiled by Michaelis, Pausaniae

descr arc.Ath.S. 60. In the prose inscriptions the goddess is called

"Άθeνa Έpγaχe," in a poetic shorthand "thea Ergane." It is by no means

proven that these consecrations go to a different goddess than those

consecrations that simply apply to "Athena" or to "Athena Polias". On

the contrary, one can prove that in all these cases it is the same

goddess, Athena Polias. There are several devotional inscriptions

which, according to their content, are addressed to Athena as Ergane,

in which this goddess is nevertheless only called "Pallas" or "Athena".

One of these inscriptions (G. 7. A . 111 217) is accepted without

hesitation by A. Michaelis among the dedications to ergans, and of a

second one (Hermes XXII p.

135) G. Robert says that with it, as in many other inscriptions, the

consecration of the ergans applies. So dedications to Ergane could

simply be addressed to "Athena", and consequently Athena was both

Polias and Ergane at the castle.

4. The find locations of all

these dedicatory inscriptions also do not indicate that there was a

special sanctuary of the ergans at one point in the castle, but least

of all that this area or temple was located on the middle terrace west

of the Parthenon. Of the five inscriptions that A. Michaelis lists,

only one found on that terrace and not in situ. (p.306). The east side

of the Erechtheum, the SW corner of the Parthenon and the interior of

the Propylaea are given as localities for the rest. Of the newly added

inscriptions, only one was found on that terrace.

5. While the

westernmost terrace was separated from the central one by a retaining

wall and, as the latest excavations have shown, even by a portico, we

see no separating wall between the easternmost and the central terrace,

but a connecting staircase, a wide flight of steps, as it occurs in

Olympia on the Schatzhauser terrace. Although these steps were actually

used in later times for the setting up of votive offerings and

inscriptions and therefore could no longer serve as stairs, that was

not the purpose of their construction. The middle terrace was therefore

not a closed area but, like the Parthenon, belonged to the large

"temenos" or precinct of Athena Polias.

H. N. Ulrichs and his

successors took the incomplete passage of Pausanias (I 24, 3) as the

starting point for their proof of the existence of a special Ergane

temple. It cannot be denied that it was permissible to look for a

temple of the ergans in the "naos" mentioned there. However, I think I

have proved in my essays on the old Athena temple (Ath.Mitt.

XII p. 52 ff. and 210) that Pausanias was further east and north of the

Parthenon when the "naός" was mentioned, and that his words with

greater justification must be referred to the ancient temple of Athena

Polias, who was also Ergane.

The excavations west of the

Parthenon, undertaken in the winter of 1887-88, have confirmed this

line of evidence, and shown the untenability of the earlier accepted

view. Instead of the expected Ergane temple, a large building (fig.2)

appeared on the middle terrace, the size and location of which is

indicated on the adjacent plan. It consisted of a large hall (p.307)

about 15 m deep and 41 m long, in front of the long side of which was

an amphitheater about 3.5 m deep. Only the foundation walls have

survived, and these are badly damaged or even completely destroyed in

several places. They were everywhere only a few cuboid layers deep,

even where the solid rock only appears at great depths. In some places

where the rock comes down to the ancient floor, foundations have never

existed; the existence of the walls can only be recognized here by the

beds worked into the rock.

Fig.2: Plan of the southwest corner of the Acropolis, showing the Chalkothek and adjacent structures.

The

materials used are partly ashlars from Piraeus stone, partly the

remains of pre-Persian buildings (e.g. pieces of Doric column drums

from Poros), partly limestone from the castle, which was extracted when

the rock steps were made.

The southern longitudinal wall is

formed by the southern castle wall itself. The northern longitudinal

wall can be reconstructed as a column position, although there are no

longer any standing traces of the columns. For the small depth of the

north porch in relation to its length can only be explained if this

room was a portico. The strength of the northern wall is also perfectly

adequate for a stylobate. The number of columns is unknown; In the plan

I have assumed 17 intercolumnias, because then (p.308) the result is an

ax width of about 2.5 m, which is suitable for the size of the building.

Nothing

has been found of the superstructure, at least none of the existing

structural members can be ascribed to it with certainty. We also do not

know how many doors were there and how the large hall was lit. In any

case, the latter must have had internal supports, without which it was

not easy to build a ceiling construction with such a large span. Of

course, the foundations for such inner columns no longer exist, but

they must have been destroyed when a Byzantine church was set up inside

the ancient building, the sparse remains of which came to light during

the most recent excavations.

What was the purpose of the building?

It

couldn't have been a temple. The main argument against this is the

shape of the ground plan, for in a temple the vestibule would be on the

short side and not on the long side. Also, a temple would hardly use

the castle wall itself as a back wall. We mustn't think of a

residential building either, because the large hall has no subdivisions

such as would be indispensable in a residential building. According to

its ground plan, the building could only have been a large magazine

decorated with a portico on the front side. One such store was the

Chalkothek in the castle, which is mentioned several times by old

writers and in inscriptions. It can be proven that the newly found

building is this long-sought Chalkothek.

The Chalkothek has

already been recognized in several buildings on the Acropolis. For a

long time, the building in the S.E. corner of the castle, on the

foundations of which the new museum is now being erected, was thought

to be the Chalkothek. Only a few scholars believed they could look for

them in the back building of the Parthenon, which is specifically

called the Parthenon in the official handover documents. Recently, at

H. G. Lolling's suggestion (p.309), the building uncovered to the

north-east of the Propylaea has been called the Chalkothek.

If

we summarize below what is known about the Chalcothek from inscriptions

and ancient writers, it will be seen that these reports are not

consistent with those earlier statements, but that they relate to what

was found west of the Parthenon on the middle terrace buildings fit

perfectly.

The most important information about the Chalkothek can be found in a decree from the middle of the IV century BC (C.I.A.

II 61), which deals with a new inventory of the objects kept in it.

This inscription first shows that the Chalkothek was an "oikema", i.e.

a special building and not just a room in a larger building. This

proves that the view of those who wanted to recognize it in the back

cella of the Parthenon is untenable. Furthermore, the words "aspides

epichalkoi en te chaleotheke aute προς τω τοiχω" indicate that the

building consisted of two parts, a room, which could be called

Chalkothek in the narrower sense, i.e. it was the actual storeroom, and

another adjoining rooms. It was assumed earlier that the Chalkothek was

provided with a vestibule, so that both the whole building and the

actual storeroom behind the vestibule could be called Chalkothek [1].

The building under the new museum did not meet this condition because

it did not have a vestibule. In our building, on the other hand, as in

the one north-east of the Propylaea, there are such vestibules.

The

fact that the above-mentioned inscription and also the numerous

inscriptions that contain inventories of the Chalkothek, as far as

their exact location is known, all (p.310) in the western half of the

castle speaks against the building under the museum have been found.

Although some of these inscriptions (e.g. C.I.A.

II 61a and 733) were located to the west of the Parthenon, i.e. right

next to our Chalcothek, it cannot be concluded from this that the

Chalcothek had to be sought west of the Parthenon, just as little as

the discovery of some inscriptions in the N.E.. of the Propylaea

justifies the assumption that it should be set north-east of the

Propylaea. Rather, based on where the inscriptions were found, one can

only say in general that they must have been in the western half of the

castle.

Accordingly, only the building north-east of the

Propylaea and our building on the so-called Ergane Terrace come into

consideration. The former is decidedly too small for the Chalkothek.

For if one examines the inventories and makes a compilation of the

items listed therein, one finds with certainty that they could not

possibly have been accommodated in the two rooms of that building. In

addition to beds, greaves, baskets, bowls, braziers, wreaths, one

inscription (C.I.A. II 678) lists 1500 laconic shields. Another (C.I.A.

II 733) speaks of 43,300 objects of one kind and also of a larger

number of different war machines. Since the Chalkothek is certainly

also identical to the "armamentarium" which occurs in a Lycurgian

fragment, it must at times have contained a larger number of weapons

(cf. Vita X orat. 852 c). H. G. Lölling himself (Top.v. Ath.

p. 344 note 1) pointed out that the building northeast of the Propylaea

was too small for so many objects. Nevertheless, he was allowed to

declare the same for the Chalcothek, because no larger building was

known in the western half of the castle that could have come into

consideration, and because the existence of one could not even be

suspected.

But now that a large magazine-like building has been

found, the usable area of which is at least four times as large (p.311)

as that of the former, we are fully justified in recognizing it as the

Chalkothek. There are some additional circumstances that confirm this

designation.

Our building is younger than the Parthenon, because

the rocky steps between the two buildings, which are contemporary with

the Parthenon, must be older than the Chalkothek because they were

originally built up to the southern castle wall. This would not have

happened if the chalcothek and the steps had been built at the same

time, for the triangle between the chalcothek and the steps was

unusable unless it was filled up and thus level with the Parthenon

terrace. The Chalkothek was thus built after the Parthenon. However,

the material of the foundations makes it probable that the difference

in construction times is not great. The buildings of the 5th century BC

are in fact regularly founded with Piraeus stones, those of the 4th and

3rd centuries with breccia blocks. Since Piraeus stones are still used

in the Chalcothek, it was most likely built at the end of the 5th or

beginning of the 4th century BC. This goes very well with the fact that

the Chalkothek is mentioned for the first time in 358 or 354 BC (U.

Köhler on C.I.A. II 61).

At

the end of the 5th century BC, the rear building of the great temple,

the Parthenon, served as a magazine for votive offerings and other

objects that were not to remain in the cella of the Parthenon or in the

open air. When this space could no longer hold the objects, either

because there were too many or because the Parthenon was used in a

different way (e.g. for its use as a treasure house, see Ath. Mitt.

XII p. 303), one built a new magazine, and that very close to the back

of the great temple. Both magazines, connected by the grand staircase,

were under the same supervision "tamiai tes theou," and the inventories

of both were sometimes carved on the same stone; this can be explained

particularly well if the (p.312) two magazines were as close together

as they actually are.

Finally, there is one more objection that might be raised. H. G. Lölling (Topogr. v.Ath. p.344 note 1) and after him also Penrose (Jour. of Hellenic Studies

VIII p. 270) have pointed out as proof that the building northeast of

the Propylaea is the Chalkothek that numerous bronzes were found in it.

For those who do not know the details of these finds, such evidence is

captivating. The bronzes, however, are not in or next to the ancient

building, but were found under it. They lay deep under the ancient

floor in a large cistern dating back to pre-Persian times. The bronzes

were therefore in the ground before the building above could be used to

store bronzes. Since they were by no means part of the Chalkothek, it

is inadmissible to use their identification to name that building.

From

this I consider it certain that the building on the middle terrace west

of the great temple of Athena was the Chalcothek. It is safe to say

this now, because the excavations on the Acropolis have been completed,

and there is therefore no longer any hope that another building could

be found which would correspond better to the old reports about the

Chalkothek.

This result is valuable in itself because it

recovered one of the largest structures in the Acropolis. But it has

another topographical significance, as we get new confirmation for the

view developed above that a special ergane temple never existed at the

castle.

The Ergane temple was usually placed where the

Chaikothek has now found its place (cf. A. Michaelis, wall plan of the

Acropolis). It was assumed to be so far south that the statues, which

Pausanias mentions as facing each other after (p.313) the precinct of

Artemis, would have space between the entrance to that precinct and the

temple. This appointment is now definitely eliminated. But the temple

could not have been located further north, either. First, no trace of a

temple has been found there. Secondly, it is impossible for an ancient

temple to have stood there, since the central terrace as such was only

made at the end of the fifth century BC. At that time, a large part of

the terrace was lowered by working down the rock. But that could not

have happened if an ancient temple had stood there. The Ergane temple

must have been an old foundation, however, because the only place

(Paus. I 24, 3) from which the existence of such a temple has been

derived clearly mentions an old cult. Thirdly, if the Chalcothek had

stood in the Ergane district and next to its temple, it would have had

some connection to the Ergane: the Chalcothek's inventory must have

contained objects dedicated to the Ergane. That's not the case. Rather,

the objects belong to the "ίερa χρηmaτa της θeοΰ", to the sacred

treasure of Polias. In C.I.A.

II 61 it is expressly emphasized that the previous stock should be

restored, "όπως σχγi kaλλίστa kai εΰσεzέstata τa προς την Theon".

Accordingly, the "tamiai tes theou" are also entrusted with the

management of the contents of the Chalkothek.

The fact that the

discovery of the Chalkothek speaks against the earlier assumption of a

special Ergane temple and that it is further confirmation of the view

that Pausanias still saw the old Athena temple must be admitted by

those who do not yet have the latter view, but which they should

now share.

WILH. DORPFELD.

1. 1. The one featured in C.I.A.

II 721 mentioned "οπισθόδομος Xaλχοθηχης" is by no means certain. The

first word in the inscription reads . . "ISOOMOLO op]isthodomo" the

second one is complete.

[Return to table of contents]

|

|