|

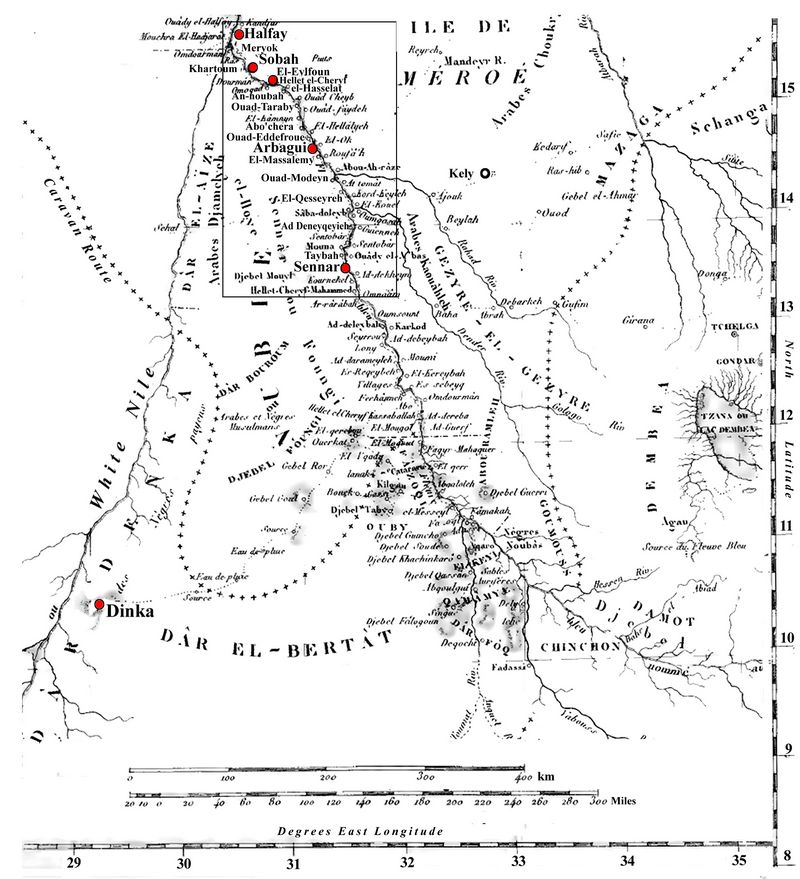

Voyage to Meroe and the White Nile in 1819-1822, by Frederick Cailliaud. (Published in 1823-1826 by the Imprimerie Royale in Paris.)

Chapter 44

Interview

with Divan Effendy. - Report on Ibrahim Pasha's expedition. - Dinka

Province. - Character and customs of the Negroes who inhabit it. -

Their food. - Interview with Toussoun bey. - Departure from Sennàr;

aspect of the country. - Passage of the Blue River. - Arrival at Halfay

(p.74).

ON February 27 [1822], at daybreak, I went up to the

city and knocked on the door of our old home. I found our good

hostesses there, and the pleasure of seeing each other again was equal

on both sides. They expressed the surprise and joy they felt at our

return, and congratulated us effusively on having escaped the dangers

we had encountered. In less than half an hour, we were arranged in our

accommodation. I immediately paid a visit to Divan-Effendy, who

commanded the garrison. He seemed charmed by my arrival, and

overwhelmed me with questions about all the particularities of our

laborious and almost insignificant campaign. When I told him that the

income from these gold mines on which we relied so much did not merit

that we prolong (p.75) the current expedition, nor that we undertake

new ones, his face blossomed; because he had no doubt that if it had

been otherwise, his turn would soon have come to travel through these

wild regions, of which I had no reason to paint an attractive picture

for him. I gave him the letters that Ismayim had sent for him after

having read them, he told me that they contained the order to provide

me with all the camels I would need to return to Egypt; that he was

also instructed to advance me the necessary funds for this trip.

As

I could obtain some in Dongofah, I only took five thousand Turkish

piastres, and I gave notice to my correspondents in Cairo, so that they

could reimburse it to the khazneh of Ismàyi pasha. Divan-Effendy told

me about all the worries he had never ceased to be prey to, either

about our fate or that of the troops entrusted to his command. The

'couriers that Ismayi sent were stopped on the roads. The rebels,

taking advantage of this total interruption of communications, spread

the most sinister rumors about the disasters of the Pasha's army. The

persuasion that this army no longer existed had emboldened the natives;

the sedition took on the most alarming characteristics. (p.76);

Already, in some villages, the soldiers who were garrisoning there had

been massacred.

Fortunately, the arrival of Ibrahim's troops had

suppressed the excitement; but there were still symptoms of

insurrection in the provinces of Haifay and Chendy. This last

circumstance was very worrying for us. The boat in which we had come

had immediately continued on its route; However convenient this way of

traveling was, it could not agree with my plans: the boat had to stop

anywhere; I would therefore have had to renounce all kinds of

explorations, and it was a course that I would only have wanted to take

at the last extremity. I therefore decided to make my return to Egypt

by land. The state of languor in which Mr. Letorzec still found himself

obliged me to leave soon. Divan-Effendy promised that he would have me

escorted to Arbagui, and that he would give me an order so that all the

village chiefs would then have me accompanied by trusted men.

I

had hoped that I would see ibises again on my return to Sennàr; but it

was no longer possible for me to discover a single one [1]. The natives

call (p.77) this bird assimbira; it is black with a few bronze-green

feathers on its wings; the beak and tail are of medium size. We also

find Sennarunibis Mane; It's called bilibily. These birds only inhabit

the valley of the Nile a few months before the rains fall; blacks

especially are very common. They are quite familiar, and often perch on

the top of cabins. At the start of the rainy season, they disappear

completely. In the countries covered with woods that we traveled, up to

10 degrees north, not a single one was ever visible to our eyes. When

these birds appear in the Nile mud, we only see a small number of them

reaching up to i'Atba.rah. We ate one on the island of Meroe; its meat

tasted like fish.

I questioned

some natives about the sudden and general desertion of the ibises. They

told me that these birds act like men, who flee, at the same time as

them, the (p.78) pernicious stay of the banks of the river, and that

they retreat towards the wooded and deserted regions of the interior,

where they feed on small reptiles and insects. This fact would once

again confirm the reports of ancient authors, who said that the ibises

emigrate part of the year to go and fight the snakes on the limits of

the desert, a benefit for which their recognition deserved great fame.

Mr.

Linan, a French traveler, whom Mr. Binks, a scholar from London,

employed to draw ancient monuments, had come to Sennàr during our

absence. He had followed Ibrahym, whose failing health forced him to

return to Egypt

I did not want to leave without having gathered

exact information on the expedition of this pasha in the province of

Dinka, and on the people who inhabit it. No one was better suited to

provide me with it than Mr. Asphar, a Coptic doctor, who spoke French,

and he obliged with extreme kindness.

Ibrahym did not go beyond

eI-Qérébyn; his illness, worsening from day to day, forced him, as I

have said, to leave command. After fourteen days of marching from

(p.77) the Blue River his troops arrived at Dinka, on the White River.

On

September 27, the majority of the negroes had fled; However, we managed

to catch five or six hundred. The village of Dinka gives its name to

the province which begins at approximately Sennâr, and continues in the

southwest very far along the river. It would have been important to fix

the position of this village; I estimate that it is at 11° latitude, in

the parallel of Fazoql. The products of the province seem to be the

same as those of Bertàt. The Negroes there are well built, strong and

vigorous; they go naked. The women gird themselves with a skin in the

form of a short petticoat; the girls only wear a small skin which

covers the lower part of their backs and is tied in front. The chief's

distinctive hairstyle was a white turban, with a plume of ostrich

feathers. The children of rich families wear a bell hanging from their

behinds; elderly people have one attached to their arm. Depending on

their wealth, women and especially girls adorn themselves in greater or

lesser quantities with necklaces and belts made of Venetian tales [2],

although Venice is not the only country where this article is made,

(p.80) ivory buttons, ivory or iron bracelets, and rings, also in iron;

when children reach the age of puberty, they have their four lower

incisor teeth removed; these teeth, according to the way of seeing

these Negroes, are useless and disfigure the face; men and women shave

their heads; they remove the hair from the rest of their husbands'

bodies, who reciprocally render the same service to them. A man can

take as many wives as he can give oxen or cows. On the wedding day, the

new spouses take care to smear their bodies and faces with a large

quantity of grease, which soon makes them exhale an unbearable stench:

in their eyes it is nonetheless a highly sought-after cosmetic, and

which in no way harms their sense of smell. They leave the marital

cabin, covered in a very thick layer of tallow, and expose themselves

to the sun to melt it and rub themselves. These frictions are the

delight of the Dinka negroes, and they obtain this enjoyment as

frequently as they can; they claim, which one can easily believe, that

they are very beneficial to their health; but it is also (p.81) a

matter of coquetry, especially for women.

Before

contracting marriage, the future must build a cabin: this is where the

nuptial feast is given. He who has the means kills an ox; he sells to

his neighbors the meat that he judges to exceed what his guests will

consume. When a negro who has become old, I have been told, has wives

who are still young, he gives his male children, if he has any, the

right to replace him with them. The women are astonishingly fertile;

They most often give birth to two children at the same time. It is not

uncommon to see a mother breastfeeding a child, followed by another who

can barely walk, and carrying two or three of them on her back in a

sort of leather haversack. If a husband surprises her woman in

adultery, he kills the man who seduced her, then drags him by the feet,

digs a deep pit, and buries him there. In winter, and in the rainy

season, the nights being very cold, they lie down to sleep in warm

ashes.

They smoke tobacco which they harvest; their pipes can

contain two or three ounces; the tube they adapt to it is a large reed

three to four feet long. Their way of living differs little from that

of the other peoples of (p.82) Bertât. They grind, between two stones,

the dough they make with the durah flour, and leave it to ferment for

twenty-four hours so that it sours; then they cook it in earthenware

vessels, and eat it hot, after having been seasoned with fat and salt,

sometimes with sour milk, or with pounded and boiled okra; in the

absence of these fruits, they dry green durah stalks over the fire,

pound them, boil them in the same way, and obtain sugared water which

serves as a condiment. They are very fond of beef flesh, and have very

little regard for that of goat or sheep; the flesh of the elephant is

strong in their taste; They also eat this from giraffe, deer, wild ox

and other animals. These meats are brought to them by the Arabs of

Bertât and Bouroum, and they give sheep or spun cotton in exchange.

Their weapons are very heavy spears (fig.2), the iron with which they are

equipped is up to a foot and a half in length and five inches in width.

They also mount straight, sharp horns on sticks, and sometimes iron

darts. Finally, they use a type of short club, large at one end and

pointed at the other. They throw this weapon with skill (p.83) at a

great distance, giving it a rotational movement, so that One of the two

ends must hit the goal. Their shields, made, it is said, of elephant

skin, are very large and very heavy.

By their courage and their

numbers, they made themselves formidable to their neighbors of Bouroum

and Bertàt, among whom they made incursions. These hostilities

sometimes attract unfortunate reprisals from the latter, who come

together to take revenge. When accepting combat, they place their wives

and children in their midst, and await the enemy firmly. As soon as he

advances, platoons of six or eight detach themselves alternately, and,

vibrating their heavy lances with a sure and practiced hand, make them

fly towards him at an interval of thirty or forty paces. If they see

themselves unable to put up any longer resistance, they flee and leave

their women and children there, who remain in the power of the victors.

If the women recognize that the enemy is too numerous for it to be

possible to face him with any hope of success, they throw themselves on

their husbands, seize them by the middle of the body and conjure them

to (p.84) not expose themselves to inevitable danger.

They yield

to these exhortations, throw down their spears, their shields, and sit

on the ground next to their women. Their adversaries then run up and

seize them without firing a shot. In the event that, although in force,

a party of negroes begins to give up, the women take part in the action

and fight fiercely if fortune betrays their courage, they show their

rage by biting everything that comes within their reach. reach, and

tear with their teeth the hands of their conquerors who come to chain

them. When an enemy leader falls under their blows, they subject him to

the mutilation of which I have already spoken, place his body on a pyre

and burn it.

Dressing wounds is reduced to washing them; if the

river is near the battlefield, the wounded person is immersed in it.

The strength and beneficent mood of the Dinka negroes make them seek

out neighboring meliks, who endeavor to attract them into their troops,

or to make them auxiliaries, by sending them messages. presence of

livestock. This is how the meliks above Sennâr are always on good terms

with these negroes. Every year, during the rainy season, they come to

Bouroum, to (p.85) their neighbors of the Goui, Rore, Qérébyn

mountains, who depend on the Sennâr to exchange slaves and cattle, and

stock up on durah. A large ox is given for two calves, five or six

sheep for one ox, a large ox for a small cow in terms of domestic

animals, females always have a higher market value. On their way back,

if they find a small village, they kidnap men, women, children,

livestock and crops. The following year, they will on the other hand

exchange the prisoners they have in their hands; and it sometimes

happens that relatives find and thus redeem some of their relatives who

have been taken from them.

Their cabins are built like those I

have already described. They use hollowed-out tree trunks to navigate

the White River, and steer them with oars with wide tips. They kill

with spears the animals whose meat they want to eat; if it is an ox,

they tie its four feet and make it fall first.

The stars, I was

told, are the object of their worship. They have a dialect that is

their own. It is assured that the negroes who live above (p.86) them

are cannibals and use poisoned arrows, and that to the west of the

river, there are other negroes no less barbaric, than we call Chelouks.

At Dinka, the river is very wide. The inhabitants of Mount Goul and

Rore, like those of et-Hérébyn, call themselves Muslims and practice

circumcision.

The Turkish troops remained eight days at Dinka;

and, retracing their steps as far as Rore, they made a small incursion

from there on Mounts Bouck and Taby, where we had gone [3] ourselves.

They took two hundred negroes from Tàby, and returned by eI-Qërébyn to

Sennâr.

Toussoun Bey, who remained head of Ibrahim's army corps,

had endeared himself to the troops. He had not allowed the captured

Negroes to be treated with this revolting inhumanity which had so often

broken my heart; he wanted their needs to be provided for as best as

possible, and above all that they should not be made to endure the

agonies of thirst. I went to visit him and he made me have coffee and

smoke a pipe. He then told me that he wanted to give me a very amusing

show. Armed with a rifle loaded with bullets, he began to take aim at

an Arab who was in the river: the shot went off, this man took the

(p.87) dive and reappeared a moment later.

The same process

begins several times; and each time the reappearance of the Arab

excites long, loud bursts of laughter from the spectators. Finally he

came out of the water and came to kiss the hand of the bey, who gave

him a few piastres. For eight years, Toussoun told me, he had been

shooting at this man without being able to catch him. I hastened to

take leave of him, for fear that he might take the fancy to start up

again a pastime which did not seem at all laughable to me. Like Ismayi,

he recommended that I tell Mohammed-AIy that he had been given an

infinitely too advantageous idea of the country where his troops had

suffered so much, without any results of any importance. As for him,

all his wishes were to return to Cairo: chiefs, soldiers, servants, all

congratulated us and wished for the happiness we would soon have in

seeing the beautiful sky of Egypt again. I would have liked to pass

through Kourdofan, where Mohammed Bey commanded; I would have found in

him a former protector, and in his doctor, Doctor Marucki, a true

friend; finally this country would have offered me a soil that the eyes

of no observer had yet explored.

I was (p.88) forced to give up

this attractive project; my unfortunate companion would have succumbed,

undoubtedly to the length of the journey. There was no one to whom I

could entrust him in the state of weakness in which he found himself. I

got myself a karmut [4] which we attached to a camel; we then laid him

down inside; and we left Sennâr on March 1, accompanied by a village

sheikh and some troops who came with us as far as Arbagui. In the

evening, we stopped at the large village of Taïbah. I was surprised to

find it abandoned; the inhabitants, already overburdened with taxes by

the pasha, seeing themselves still plundered with each passage of

troops, had decided to retire to the other bank of the river, and lived

there wandering in the woods. Masters of our time, we only did short

days of five to six hours of (p.89) walking.

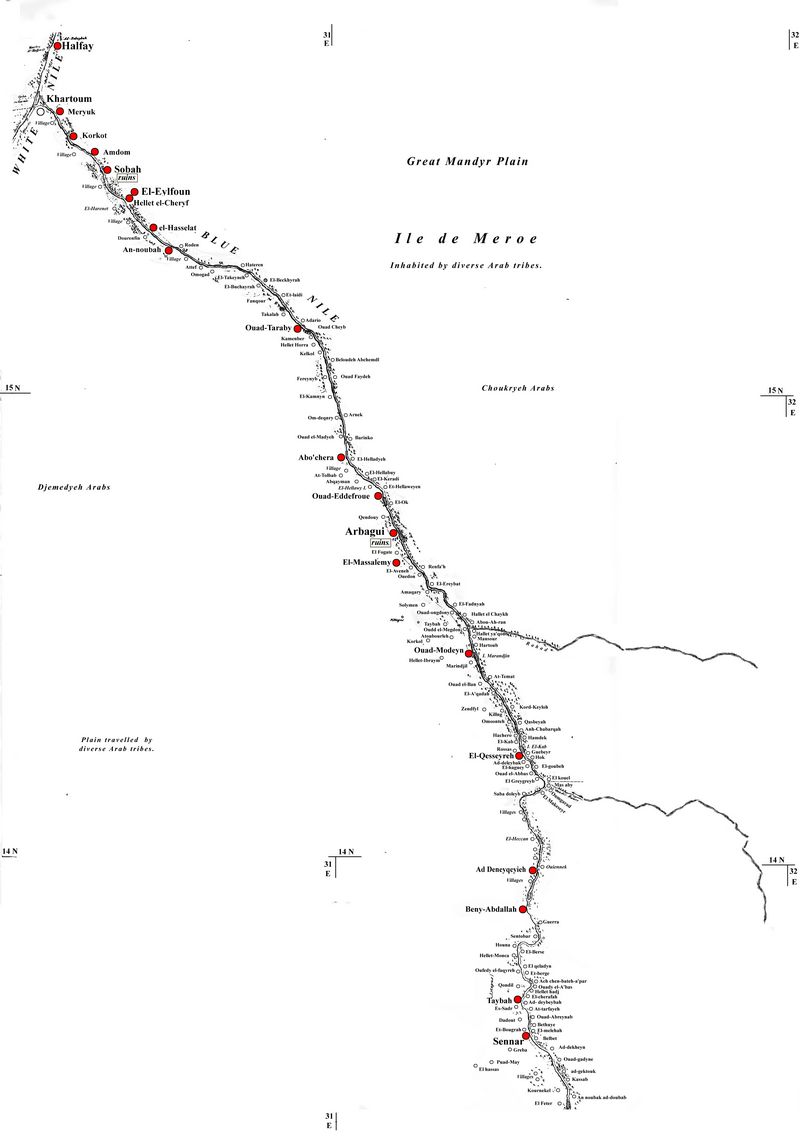

We

slept on March 2 at Ad-deneyqeyieh, a village on the river, and also

almost deserted; the 3rd, at eI-Qesseyreh, and the 4th at Ouad Modeyn.

We had passed through several villages where the same solitude still

reigned. I was bored with the sad and tiring monotony of this flat

country, where the view is constantly lost on immense and uncultivated

piaines, and only at large intervals discovers a few bouquets of

acacias, and especially nebkas, trees which are very common up to the

height of Ouâd-Taraby. Through Mirage Window, these masses of plants,

which almost always appeared in the distance to the west, had the

appearance of green islands dominating above the waters.

Ismayl,

who had not forgotten the murderous influence that their stay in Sennâr

during the rainy season had exerted on his soldiers, had charged me

with looking for a suitable position to camp there when this disastrous

time returned; I had received the same recommendation from

Divan-Effendy. I judged that the neighborhood of Ouad-Modeyn met your

required conditions, and I let them know. I subsequently learned that

this opinion had been adopted.

On

March 5, the road deviated further from the (p.90) river we left behind

us many large villages, a second among others called Taïbah, located a

league from the river. Everywhere we passed, the kaïmajtans [5] eagerly

came running to us, to learn news of Ismâyl's expedition. We slept at

el-Massalamy.

On the 6th, we rested for an hour in the woods of

Arbagui, a memorable place in the splendor of the Foungis. It is there

that, coming from the River Bianc, they once fought the people who

inhabited the Sennâr, remained victorious and made themselves masters

of the country. Arbagui was a fairly important city, judging by the

ruins of buildings built in earth which are still scattered on its

site: woods populated by monkeys and other animals today surround these

ruins and partly cover them. We left the good sheykh who accompanied us

here and two hours later, we stopped at Ouâd-Eddefroué, to spend the

night. On the 7th, we passed Abo'cherâ, a large village of which I took

a view which will be enough to give an idea of all those in Sennâr.

(Vol. I, pl.VIII.) (p.91) We came to sleep at Ouàd-Taràby. Each day

brought us a few leagues closer to Egypt and there. France this thought

somewhat revived Mr. Letorzec's strength; the hope of seeing his

homeland again was finally reborn in his soul.

On March 8, at

two o'clock we arrived at the village of An-noubah, where the boats are

for passing the new ship; we had to cross it here, to follow the right

bank. At the sight of us, the boatmen fled; Our clothing of Osmanlis

had frightened them. We made every effort to encourage them to return

without fear; they had left their boat at our discretion but they had

taken the oars; my embarrassment was extreme. I showed them from afar

the money I wanted to give them; They seemed to believe that it was a

misleading suggestion that I was presenting to them. Finally I threw

them a Spanish piaster, and left so that they could come and collect

it. They approached trembling; one of them held out his hand as if to

give me back this coin, which seemed to them to be a very generous

salary from a man of my dress.

These poor people told us that

every day the soldiers beat them to pay for their pain; (p.92) that

this was the motive which had led them to flee. We got on a boat with

our luggage; two others swam our camels across. Over three quarters of

its width, the river had only 4 feet of water. We had only to be proud

of the zeal of our boatmen, who, for their part, were very pleased, but

very surprised that a Turk had provided them with such a good windfall.

We set foot on land in the province of Haifay, formerly the Island of

Meroe. After an hour and a half of walking, we slept in el-Hassalat, a

large village near the river.

I had almost always followed the

west bank of the river on my way; I now wanted to follow, as much as

possible, the eastern bank, to acquire a more accurate idea of the

country, and to accurately recognize the large bend that the Seuve

makes in the province of Robàtàt. On March 9, we encountered el-Eylfoun

and Hellet-Édris, two villages of some appearance, one of which is a

quarter of a league and the other half a league from the river.

We

passed early on the rubble of Sôbah I stopped there again, to travel

them again; I found nothing more than what Gavais observed when we then

left (p.93) the villages of Amdôm, Korkoi, Meryok. Here the road

deviates from the river to cut the angle that the Nile does in its

junction with the Blue River. The whole country between Ei-E'Ylfun and

Halfay is appointed Gouba Ayeli. At seven o'clock in the evening, we

arrived in Halfay.

Footnotes:

1. I consoled myself by

thinking that one of these birds, whose remains I had sent to Cairo,

was safe, but I learned later that Mr. Champion, vice-consul in Cairo,

whose home it was he had deposited and relinquished it in favor of a

Prussian naturalist. Let us hope that this curious object, lost to me,

will not be lost at least for the sciences because I learn that this

traveler has just arrived in Berlin, where he is busy publishing the

materials he has collected.

2.

We call conterie, Venice, different species of glassware, and this name

has spread in the trade, although Venice is not the only country

where this article is manufactured. We should write accounts.

3.

This circumstance, which upset me so much, really was the cause of our

salvation by prolonging our stay in these countries; impatient of the

yoke, we would have found ourselves in the middle of the uprisings and

massacres of which they later became the scene.

4. A kind of long

basket, in which the Arabs transport their women when traveling. (see

vol I. pl. LXIII, to the left of the drawing,)

5. Junior officers, responsible for ensuring the return of contributions.

[Continue to Chapter 45]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |