|

An Attic Cemetery

(Article written in 1893, published in Athen. Mittheilungen XVIII, pp.73-191)

Since

the end of the excavations on the Acropolis, the Greek general ephoria,

headed by Mr. Kavvadias, has been pursuing the plan of uncovering

burial sites on a larger scale and under more precise observation than

before. The reports of Mr. Stals in the Δελτίον

and also in these communications [1] bear witness to the success which

these works had in the Attic landscape, at the grave of the Marathon

fighters, at the burial mounds in Velanidesa and Vurva and elsewhere.

In connection with these goals, it must have been especially desirable

that the General Ephoria was authorized in the spring of 1891 to

conduct research in Athens itself on an extensive plot of land

north-west of the city. The execution of this excavation was also in

the hands of Mr. Stals; he has spoken about them, in particular about

the finds made by this excavation; have been brought to the National

Museum, briefly reported [2]. He was assisted in the work as the

architect of the General Ephoria by Mr. Georg Rawerau.

The

undersigned have been granted full freedom to attend the progress of

the excavations, and as we are about to publish our notes, we are

compelled to acknowledge the gratitude which we guests in Greece owe to

Greek hospitality and scientific liberality. We hope that what follows

will help the (p.74) plan which the general ephoria has in mind to

expand the knowledge of Greek burial customs.

We are aware of

how much what we offer lags behind other grave publications ( i,e,

Italian) in terms of clarity and detail in describing the contents of

the individual graves. For we have made the distinction in the

treatment of the oldest graves and those of the later epoch that we

believed it necessary to give the reports of the finds of those with

all the details, while in the case of these we have restricted

ourselves to the reproduction of the typical phenomena. Thanks to Georg

Kawerau's friendly cooperation, we can make our notes clear with the

plan on plate 7 and some grave views. For the text, it should be noted

that Brückner observed the finds in the first two rectangles (A. B) and

part of the third (C), while Pernice observed the later uncovered

graves. We divided the work during the preparation, so that chapters I

and III were written by Brückner, II and IV by Pernice. But what

ultimately goes back to one and what goes back to the other is

difficult to separate.

I. Location and history of the cemetery.

The

site on which the graves to be described were found is on the south

side of Piraeus Street, opposite the Hatzikosta orphanage and at the

same time adjoins a side street, the Όδός βασιλέως Ηρακλείου [1]. The

owner who gave permission for the investigation is the aide-de-camp to

His Highness the Crown Prince, Colonel Sapuntzakis; Later on, the

(p.75) excavations spread to the property of the widow Karatzäs. One

might expect to find very old graves in this place.

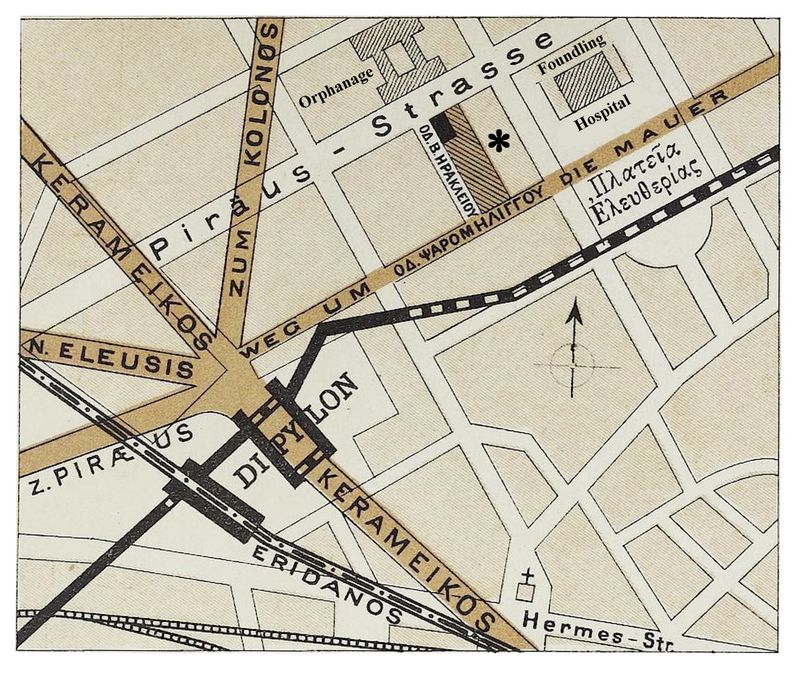

Plate 6-1: Map showing location of the grave sites (in hatched area beside asterisk).

For when the

foundations for a residential building were laid on the corner property

between the two streets a year earlier [1], the ephoria had already

observed important graves: this is where the stately, ancient amphora

comes from, which is the oldest representation of the fight of Herakles

with the 'Netos' offers, hence also the crater, which received the

review it deserved in the last year of this journal for the sake of the

enlightenment it provides about the further development of Attic

geometric painting [2]. To the east of the property of Sapuntzäkis up

to the Πλατεία Ελευθερίας [3], rich grave finds had been made from 1871

before the dwellings located there were performed, also going back to

the remote period of the Geometric style and certainly reaching back to

the fourth century. At the corner of the said square there is still a

grave stele with a relief 1 1/2 m under the present floor, which was

left in the ground [4]. Graves have also been uncovered on the other

side of the Piraeus road; for behind the orphanage the Berlin Thon

pinakes were found, the depiction of a funeral procession rich in

figures, the decoration of a tomb from the sixth century [5].

As

corresponds to the location of this whole area north-east of the

dipylon and close to the city wall, a wide field of death had spread

out here. From what we know about the location of ancient cemeteries in

general, this is not surprising given the time when the Themistoclean

(p.76) city wall existed, separating the outer from the inner

kerameikos. It is more remarkable that 300 years earlier the same room

belonged to a large cemetery that extended beyond it. For the old tombs

that have been found right next to Dipylon and on the Themistoclean

city wall are so dense that Stephanos Kumanudis [1] concludes from

their location that the city's peribolos must have been narrower in

their day—these tombs are well known , which gave rise to the usual

designation of dipylon tombs and dipylon vaults, must be associated

with those uncovered on the Sapuntzakis property and in its vicinity

and will then expect to find more structures from this epoch in the

300m wide gaps. We have no information as to whether the cemetery,

which can be assumed to be continuous, extended further to the east and

west during the Dipylon period. But even if that is not the case, the

ascertained extent of the cemetery is large enough to justify us in

drawing conclusions about the development of Kerameikos.

The

area separates the outer from the inner Kerameikos. It turns out that

it was not the Themistoclean city wall or, before that, a possible

Pisistratic city wall that divided the two quarters, but it is likely

from the location of the cemetery that in the Dipylon period the closed

settlement in Kerameikos had its limit at the cemetery - there , where

today the ορος Κεραρεικου still stands. Only as a result of an

increased development, the cause of which was the strong upswing of the

potters' guild, the partial displacement of their workshops by the

pisistratic expansion of the market and the establishment of the

academy, did the borders become too narrow, it seems, and it a new

quarter arose beyond the old cemetery, the (p.77) outer Kerameikos.

One

more thing can be deduced for the population of the oldest Kerameikos

from the tombstones and graves of their families. Even a free Attic

δημιουργός will not appear in the age of σιδηροφορεΐσΟaι without the

weapon ornaments and accordingly will not be buried without it;

therefore the finds of weapons would not speak against the graves of

κεραμείς. But if we behold the rich pageantry of the funeral procession

on the great tombs which have been found here, and survey the long line

of carriages with fully armed men, we are led to suppose that knightly

landowners kept their courts beside the potters' workshops . So old was

the friendly neighborly relationship that connected the κεραμεύς with

the nobleman and later found its eloquent expression in vase paintings

and inscriptions [1].

For the sake of completeness, an oral

message from Mr. J. Palaeologos may be added to these general remarks

about the time when the cemetery was used north-east of the dipylon.

According to his clear description, during the excavations he observed

near the then Ludwigsplatz, he also found a grave at the greatest

depth, the edges of which were framed by individual stone slabs (p.78)

and which contained a jug. According to this, it would appear that

burials have been going on here since Mycenaean times. We are not aware

of such old graves here.

The overview plan on Plate 6.1 shows

the location of the property where the excavations took place in 1891.

Out of consideration for the rubble to be excavated and how the rubble

to be salvaged, the area had to be refrained from being completely

cleared. Instead, individual rectangular shafts of about 8 by 12 m were

dug and the rubble of the newly started shaft was thrown into the

excavated shaft each time. Eight such shafts have been dug. The first

three and most important ones are included in Herr Kawerau's plan on

plate 7. The eighth, which was only opened in the spring of 1892 and is

only 50 m from the Themistoclean city wall, was taken by Pernice and

reproduced on plate 6, 2.

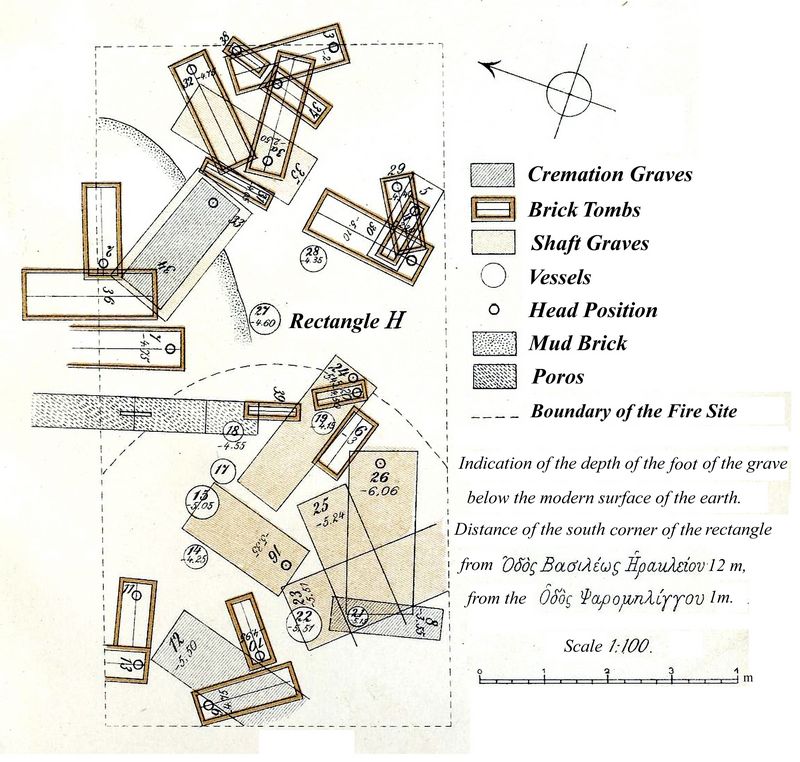

Plate 6-2: Plan of graves in Rectangle H.

In total, our records contain

information on 231 graves. However, the number of graves actually

uncovered is somewhat higher, since at the beginning of the work we

neglected to number some of the amphorae in which children were buried

and also some poor ostotheks and to enter them in the plan. Of the 231

tombs, 19 are from the Dipylon period. Apart from about 5-10 tombs in

the top layer, the rest belong to the sixth to fourth centuries BC—for

they contain the usual painted vases—mostly to the fifth and fourth;

Graves with strictly black-figure vases have been found remarkably few,

so that it seems as if the cemetery was little used after the Dipylon

period, and was only used to a greater extent after the erection of the

Themisholdean wall.

Among 186 of the more recent graves

described in our records were 45 cremation graves in which the body was

burned on the spot (p.79) 8 ostotheks (it has already been noted that

this figure is too low for the whole is); 43 shafts in which the body

was buried; 60 brick tombs, with buried corpse; 17 clay jars with

buried children's corpses (this number also has to be doubled in order

to get the true proportion of the entire find); 10 stately graves made

of large stone slabs put together, the corpse buried in them. In 3

large stone sarcophagi the corpse was buried.

After clearing

modern masses of rubble that may have gotten onto the derelict property

during the excavation of the neighboring houses and the construction of

the Όδός βασιλέως Ηρακλείου, the workers initially encountered a layer

of loose soil and lots of rubble. Beneath this layer of rubble lies the

old cemetery, which was used from the Dipylon period until around 300

AD. Before it was buried, it naturally had a wavy surface, caused by

lower or higher burial mounds that had been built over the natural

ground using the soil excavated when the grave was laid. Depending on

the height of these elevations, the layer of rubble had a thickness of

1.20 m and more, at the southern end even up to 3m. For the height

determinations within the cemetery, we have assumed the level of the

groundwater for the large plan. It turned out that in antiquity the

groundwater had a much lower level; for the graves reached down even

more than today's mirror and the earth was burnt at the shafts of the

burnt graves.

The coals of the pyre lay deep in the water

several times. The floor level of the old cemetery was around 1.90 m

above the level of the groundwater at the time of the excavation; it

arose from the presence of an extensive sacrificial site at the end of

the VI century under the tumulus A mentioned later (p.80), which we

shall discuss in detail below; for these sacrifices will have been

offered on the ground. It also resulted in agreement from several

smaller sacrificial sites and also from tumulus B, where the sole of

the edge walls and a stucco line in front of them lay at the same

height. It is finally confirmed by the fact that the graves are

consistently below this floor: the poor brick graves and the even

poorer amphorae with cattle corpses are often only a little below. Only

in two places does the grave reach so close to the floor level that a

mound must have been used to cover it. But the erection of tumulus B

and the sacrifices at the site of tumulus A are now separated by a

period of at least 150 years. This is important, because it shows how

the floor has not increased significantly at the time when the cemetery

was used most actively, despite all the excavations, a fact that

certainly does not come about without special care, but probably only

because of the state surveillance of the burial ground has come. And

since we come across the evenly grown clay soil just below the

designated sacrificial sites, the soil cannot have been significantly

lower even in the Dipylon period.

In other words, since people

continued to be buried here from the same floor in the 5th and 4th

centuries, there can only have been little hesitation in disturbing the

peace of the dead; the bones and the strange weapons and harnesses of

the long-forgotten Dipylon time one stood when digging a new pit, such

as e.g. B. appeared at the laying out of graves Nos. 3t and 4t (plate

7, B), with the same inquisitive feeling towards the moderns in their

scientific excavations. Anything that was a hindrance was cleared aside

and the place cleaned up for its new owner. After all, with such great

separating periods of time, this is not surprising, the new era laid

claim to the ground, which (p.81) must have been precious enough at the

time. The old tombs had fallen into disrepair, the desolate place

henceforth appeared adorned with beautiful tombs of shining marble. But

anyone who overlooks the criss-crossing of graves on our attached plan,

which almost all belong to the period of the white lekythos, will also

recognize that the bones of people who were closer in time were not

treated with much more consideration at that time. It is true that the

wealthy family, who buried their member in a stone coffin, will have

provided for a suitably dignified tomb, so that the gravedigger was

already prevented from disturbing the dead by the outward sign. But in

the case of the graves of the less well-to-do, who will have preferably

found their rest here on the side away from the main streets, the

earthen and brick graves and the fire shafts cut arbitrarily into one

another; at least the shafts of such graves were not scrupled to be cut

into.

We cannot prove with certainty that people would have gone

so far as to destroy the grave itself; nevertheless the crowded

position of these tombs testifies to how poor the tombstones must have

been, which could so easily be removed when a new tomb was laid on the

site of an older one. For the owners of these tombs, the Solonian law,

which ordered the preservation of the tombs, seems to have had little

application.

It is all the more remarkable how subsequent times

related to this burial site. None of those marble grave pillars, which

usually bore the excavators on the surface of the Attic cemeteries with

their dreary sobriety, have been found here, nor any of those graves

that are so common in the higher strata of the Hagia Triada, made of

roughly hewn marble slabs of the lowest sort put together without joint

closure. The old graves have remained untouched.

Rectangle H

(cf. the plan in Plate 6.2) shows that two groups of graves can be

distinguished according to their elevation. The graves 2, 3, 3a, 4.

(p.82) 8 are so considerably above the other tombs of this rectangle

that they cannot be laid out from the same floor. While these latter

are shown by the grave goods to be from the VI to IV centuries, the

ones mentioned contain nothing of the sort. Only in grave 4 was a glass

bead and a clay figure disfigured to the point of indeterminacy; apart

from the cremation grave, there were 8 poor brick graves. A cremation

tomb built just as high above the tombs of the IV century is found in

the fourth rectangle. There is also a brick grave, which contained an

unadorned lamp as an accessory, in accordance with the later widespread

custom. Within the layer of rubble, two brick graves without any

objects were also found in rectangle C, 1m deep; they are not indicated

in the plan. A grave was also found in the rubble layer close to

tumulus 13.

So there were only a few scattered graves in this

heaped-up layer: we cannot exactly determine their number, because it

is possible that during the quickly carried out clearing work some of

the graves, which were always very poor, were not noticed by us. Above

all, the cremation graves prove that the heaped-up layer dates back to

antiquity. It was clear that it was not gradually formed by alluvial

deposits. Their coarse rubble, mostly building rubble from somewhere,

was heaped up over the old burial mounds, creating a new surface 2.2 m

above the floor level of the old cemetery. Some sherds of the latest

black-glazed vessels have been found in the top layer, but nothing to

suggest late Roman or even more recent times.

We should perhaps

have to content ourselves with pointing out the peculiarity of these

strata and refraining from explaining them if they were not repeated in

a clearer way elsewhere. Located nearer the gates and the great

highways, the cemetery at the Hagia Triada has been much used (p.83) at

all times. There, too, it can be seen that the graves of late antiquity

were laid out in such a way that they left the earlier ones untouched.

The tombs of the Roman period are at about the same level as the tombs

of the fourth century BC, such as ie. next to the tomb of Demetria and

Pamphile, at the same level as its base, are the marble slabs of a late

tomb. Here, too, a high deposit was made in antiquity. Recently, this

has been shown particularly clearly in the excavations, which Mr.

Mylonas conducted in 1889 on behalf of the archaeological society. The

tombs laid out in Roman times have left the natural soil into which the

older tombs led almost untouched.

Already Ath. Rusopulos, who

started the excavations of the cemetery at Hagia Triada, received the

impression that the building up was not done gradually but all at once

[1]; this emerges from the explanation which he drew up for it. He

believes that Sulla built a dam here to bring siege engines up to the

city wall at this point. The date of the tombs above and below the

deposit would agree with this assumption, however, apart from the fact

that the same phenomenon in our excavation field would remain

unexplained, the assumption that Sulla's attack was directed against

this very spot is also based on this assumption. serious concerns [2].

It is not credible that a region so close to the main gate of Athens

could have remained unguarded by the defenders, and the siege engines

were hardly to be associated with a night raid, which, according to

Sulla's Hypomnemata, begins with the scaling of the wall served.

The

accumulation at the (p.84) Hagia Triada and our excavation site to the

east of it is more likely explained by the determination of the place

as a cemetery itself

It was neglected and desolate in its heyday,

the troops of Philip V of Macedonia had devastated it, only a few

magnificent tombs were still standing, and useless hands had an

opportunity to immortalize the name on them. No wonder that the

Athenians of about the first century BC tried to make use of these

places close to the gate and close to the wall.

Looking back,

increased piety and the law prevented the removal of the tombs of the

glorious fathers for profane reasons: the resistance that S. Sulpicius

found among the citizens testifies to the fact that S. Sulpicius found

the place for the tomb within the city walls of M. Marcellus [1]

coveted. One helped oneself by pulling a protective layer of earth over

the θηκαι προγόνων, and thus bequeathed to later posterity the

possibility of enjoying the fresh view of ancient Athenian civic

customs. The considerable raising of the floor of the cemeteries had

the necessary consequence of weakening the city walls, so it is

advisable to start the raising after the capture by Sulla, when the

Athenians, in the midst of the pacified Roman Empire, had ceased to

take care of their city walls, του δέ τείχους ρ.ηδεαι3ίς, οτε σύλας

τούτο διε'φθειρεν, άάιωοεντος φροντίδας, as Zosimos 1, 29 reported from

the time of the Valerian.

With such a procedure it was

inevitable that, although the bones of the ancestors remained

untouched, the tombs were damaged. But even there, at least in places,

piety was allowed to prevail. The road that cuts through the cemetery

at the Hagia Triada could not be raised well, so it now led through the

4 and 5 m higher cemeteries of the (p.85) Roman period. But the tombs

that lined the roadside, the reliefs of Dexileus and Corallion, the

tall stele of Agathon and his family, remained visible, and the strange

relief of Charon, despite its unappealing form, was placed on a rasis

that originally did not suit it listened to, and the base was

previously underpinned [1]. Even in the post-Christian period, the most

attractive find of the excavations of Lord Mylonas, the tombstone of a

distinguished Athenian woman, who strides along in a solemn pose as a

hydrophore, was used for decoration in the peribolos of a late

sanctuary that was founded here in the midst of the tombs.

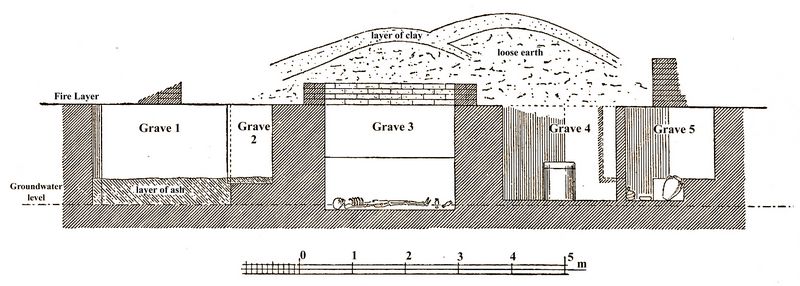

Fig.1: Section of the area of Graves 1-5, showing overlying layers.

A

more radical approach was taken to covering the old cemetery on our

excavation site with the tombstones. Because apart from a few very

insignificant tombstones [2], almost nothing has been found of the

stone decoration of the tombs. And yet it can be assumed with certainty

that similarly rich funerary steles rose above the stately marble and

porous coffins, as on the Hagia Triada. For even a wealthy Athenian

family did not endow their dead richly in the IVth century BC, as the

tomb of Dionysios on the sacred road testifies, in which, under the

magnificent Naiskos, besides the bones, nothing more than φλοιοί αυγών

κοινών [3] was found (p. 86) have been.

In order to be complete

at this point about the remains of tombstones noticed on the surface of

the cemetery, we still have the sherds of a strictly red figure

Lutrophoros with a depiction of a prosthesis and the fragments of the

goblet-shaped openings of two clay lekythos [1], which alone are 6-10

cm high, both according to their size and the height of the find, must

have belonged to tombs and not to grave goods. So before the site was

buried, all stones that could be reused were cleared away; for apart

from the firmly attached remains of two low-lying peribolos walls,

nothing has been discovered of foundation stones and bases.

Only

two tombstones resisted the destruction of the cemetery because of

their simple material, two tumuli, which we want to describe in more

detail in order to illustrate the type of graves underneath them and

their position in relation to one another with a few examples.

When

in the first rectangle the upper stratum of earth had been raised to

about the depth of the old surface of the cemetery, the intersection of

the strata in the eastern wall of rubble showed that the upper stratum

of rubble had spilled over an older arch of earth; compare the adjacent

cross-section of grave I to III (fig.1.) and the plan on plate 7, AL

The old loamy heaped-up earth rose almost in the middle to a height of

1.30 m, it fell towards the sides so that the late layer of rubble

reached down all the deeper there. Below the deepest points of the

descending line, which, due to the difference between concealing and

covered soil were clear, remains of mudbrick walls became visible,

first in the excavated first rectangle A at two points of the shaft at

a-b, then, when the work encroached on the second rectangle (B), also

at a third, in the east wall at a.

Upon closer digging, it

then turned out that these were the remains of a peribolos wall that

had been preserved during the work (p.88), which ran in an arc around

the earth bracket. We have followed them into the ground, namely at A,

a, here to a length of more than 3m, were able to determine a height of

8 clay brick layers for them and at the same time, from the wide curved

line that they described, we could determine that the The tumulus,

which it surrounded, must have reached far into the neighboring

property, whose house wall prevented us from further advance. If, as it

appeared, it was roughly circular in plan, it must have been about

10-12m in diameter. Analogous to the tumulus of Alyattes or, to keep to

smaller proportions, the tumulus of Menecrates in Corfu, the visible

debris cone had risen above a vertical κρeπίς, which in our case

consisted of a wall of mud bricks.

Only a small segment of the

tumulus fell to our excavation area. In this lie two graves related to

the structure of the tumulus; the burial shaft of No. 3 was announced

by a low mudbrick border, on three sides they were stacked four on top

of each other, they could only have been put there for some purpose for

the funeral ceremony, on the fourth side they were missing because

that's where the excavated earth. In the middle of the enclosure the

vertical shaft went about 2.40 m deep, down to below the ground water,

in a length of 2.40 m and a width of 1.10 m. On one of the long sides

there was a ledge, a step, apparently made to lower the coffin more

easily. On the bottom lay the corpse stretched out, its head to the N.

The workmen fished out of the ground water more than half a dozen very

sketchy lekythos: on one was a horse-drawn carriage, with a woman

seated in front of it, on another six men, except for one, who sat in

their midst, standing together in a cloak, only a lekythos with a fine

yellow coating seemed to be of a more careful kind. There was also a

thin round disc of bone, 0.055 (p.89) in diameter, with a small hole in

the middle, apparently a spindle whorl. It had been a woman's grave

afterwards. The poorness of the finds was disappointing given the care

taken in the construction of the tomb.

The second tomb to the

south, No. 4, had a square shaft. It was not quite so deep, but reached

down to about the level of the ground-water; at the bottom was a round

cista of Poros containing a bulbous bronze urn with the calcined bones.

The more detailed description will be given along with the illustration

in Section IV.

From the course of the layers above the two tombs

it was evident that these were not sunk into the already existing

tumulus, but that this and the peribolos wall were prepared only after

the construction of the second tomb, which was also recognizable as the

younger one from the upper layers a process of gradual formation of

such a great cairn, of which the burial mound at Velanidesa affords

another example. The time of the graves is determined not only by the

content, but also by an older layer of sacrificial fire extending

horizontally on the base of the tumulus and perhaps even beyond. Its

narrow blackish and dark red stripe reached under the mud bricks of the

peribolos wall as well as under the edging of tomb no. 3, it extended

over the tombs to be mentioned further, which are uncovered around

tombs no. 3 and 4 [1]. The layer must then be younger than these graves

and older than those graves. In fact, the numerous crockery that lay in

the strip next to the charred remains of grain and poultry bones were

of an older character than the lekythae of Grave No. 3. They consisted

mostly of thick clay plates, the center of which occupies a large black

ray rosette ( p.90) (see figs.2 and 3).

There

were also vessels whose rims were decorated with animal stripes, e.g.

B. Ebern, was still painted in the manner reminiscent of the Corinthian

vases. A graceful hydria, glazed in black, showed a small four-horse

chariot in a recessed field at the shoulder, whose austere manner was

still reminiscent of the style of the Francois vase. Apparently all

these vessels, after having served with the sacrifice, were thrown onto

the sacrificial parts [2]. We have no guess as to which dead or who in

particular these sacrifices were intended for. We cannot say anything

about the extension of the sacrificial area either, because on the one

hand it may have spread further to the neighboring property, on the

other hand, if it extended beyond the borders of the tumulus, it almost

had to, as a result of the many grave excavations of the 5th and 4th

centuries BC to have disappeared. But the layer was important for

viewing the cemetery, insofar as it indicated the level of the floor

for the VI century BC, a level that had not changed even up to the V

century, since the lower edge of the presumably walls of

Peribolos, dating from the beginning of the 5th century.

(p.91)

Whoever bought this place for his family's burial place at the

beginning of the 5th century BC found it leveled. And yet it had

already been cut through by graves of various kinds. Grave No. 1, which

encroaches on the area of the later tumulus, was a 1.90 m deep

cremation grave; in the middle of its floor ran a channel, which

continued up the narrow side walls: the same device, probably for

better combustion, which has also been observed at Vurva and

Velanidesa. According to the tombs there, the tomb contained a very

deep layer of charred wood; only the mouth of a highly archaic

lekythos was noticed (with a shape like that in Furtwangler, Description of the Berlin Vase Collection, Plate VI, 174).

Grave

no. 2, also a cremation grave, was laid out a little higher, 1.40 m

below the layer of fire and had one narrow side cut off from no. 1, so

it was younger than this. The layer of coal had the usual depth of 0.06

to 0.10 m in the usual cremation graves. Nothing was noticed about the

additions.

The two dipylon tombs surrounding tombs 1 and 2 are

more interesting because of the finds made in them [1]. As

eyewitnesses, we can only report the opening of No. III, but our

observations began immediately after the previous clearing of I, so

that we were able to get precise information about it. The grave

reached down to 1.70m below the sacrificial layer, had an impressive

length of 3.10m and a width of 1m. At its bottom the corpse had been

stretched out, its head to the north; with him lay a narrow golden

diadem, at his feet a row of dipylon vases. But a meter above the

bottom of the grave, in the middle of its shaft, the fragments of a

huge vessel were found close together, which was later put together in

the (p.92) museum up to a height of 1.80 m.

We were to see the

same facts when they dug down south of tomb No. 4 under the

well-preserved part of the peribolos wall. Hardly had the layer of fire

broken through beneath it than two large blocks were found within a

shaft that could be felt, which had been thrown in before the area was

leveled, presumably when the sacrificial room was being prepared. The

material of this was a hard limestone; one block was a slab 0.80 m wide

and just as long preserved but broken at the top and bottom, the other

block was a square pillar (0.28 by 0.23 m), somewhat pointed at its

smoother end.

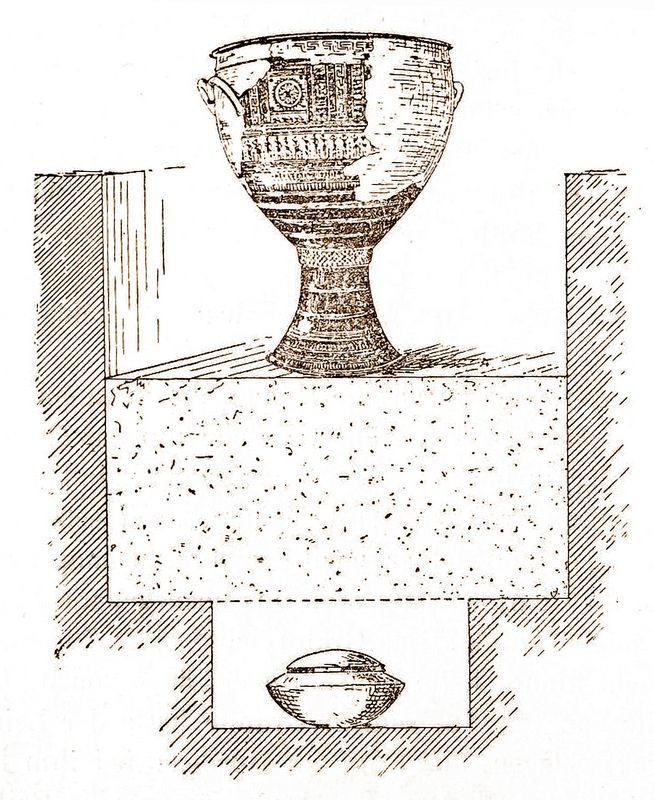

Fig.4: Dipylon vase overlying bronze urn in grave south of Tomb 4.

After

lifting the vase, we dug down, following the hard edges of the shaft.

Another layer of rubble of 45 cm had to be removed, then the shaft

narrowed on the two long sides and soon we came across the 0.85 wide,

1.70 m long grave in the middle. To the east stood a bronze urn,

containing the few calcined bones of what appeared to be a boy or girl.

The bronze was so thin that the urn, which was already slightly dented

by the weight of the earth, broke when it was removed.

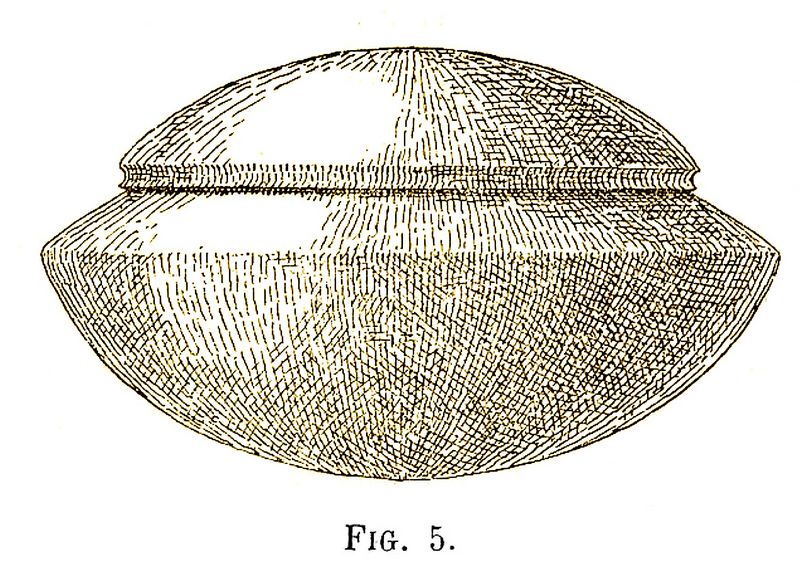

The

above sketch (fig.5) was made when the urn was still in the ground: it

is a broad urn, closed with a domed lid. Toward the center of the tomb

lay a large amphora—the height of the tomb was evidently not high

enough to place it—next to it were two cans, a skyphos, and a jug,

close together and all well preserved; (p.94) they were only given at

the last act of the funeral, at the burial of the urn and did not go

through the burning of the pyre. First of all, in contrast to opinions

which have been expressed earlier regarding the use of the large

Epipylon vessels, it is evident from the find facts presented that the

large vessels with the rich depiction of the funeral procession were

not used as ash containers, but because they were placed over the

associated graves were found when they served as tombs. This was

recognized when the Netos amphora was discovered. Our excavations at

graves II and IV provided two further pieces of evidence. At II, a

dipylon grave that was partially destroyed by a later cremation grave,

the shards of the associated grave vase were found 1.20 m above the

grave's floor, while at IV they were found 0.90 m high at the head of

the corpse. Thanks to the sacrificial layer that was spread over it

early on, we can get a clearer view of the original condition of a

dipylon grave from Grave III.

It certainly seemed as if the

large vase stood in its original position; Of course, when the wooden

ceiling of the tomb, which had been lying on the steps of the shaft,

rotted and as a result the falling earth filled the tomb, it must have

sunk by about 30 cm, and this sinking must have happened before the

construction of the peribolos wall be struck, since the upper rim of

the vase almost immediately abutted the bottom surface of the peribolos

wall when it was uncovered. According to this, she would originally

have stood with a little more than her foot below the floor level

inside the grave shaft, which, since the foot of the vase is so richly

ornamented, was only filled with earth up to the lower edge, so that it

remained visible (see fig.4).

After that, the burial shaft was

not completely filled again or a mound of earth was even built over it

- in none of the dipylon graves we observed (p.95) were there any signs

that it had been elevated by a tumulus, no matter how low - but the

grave was only covered with soil up to a moderate height, and a pit

remained in the grave shaft, which together with the tomb marked the

grave. One could not avoid the assumption of such a pit even if one

thought that the large vase above grave III and also the sherds above

I, II and IV only got into the grave shaft when the cemetery was

cleared up, the tombs would have objected originally stood next to the

graves.

Even then, there would still have to be an open spot

to salvage the vase from Tomb III as well as it came to light. It would

be extremely strange if one had dug into each individual grave at that

time in order to set up the vessel of III in the shaft nicely,

especially since the upper edge was then cut off. In reality, one would

doubtless have smashed the body and base of the vase with a few strong

blows and buried the shards somewhere. It is precisely due to the fact

that they were placed deep that so much of the clay tombs of the

Dipylon period has survived, in contrast to the certainly much more

numerous clay lekythoi and lutrophori that are so rarely and

incompletely found today as tombs [1 ].

We turn to the

description of the second earthen mark (B), of which the work led to the

discovery. To the south between (p.96) the first and second

rectangles, when the higher layers were being excavated, a round, thin

stucco layer was found. The circle he enclosed was eight feet in

diameter. As could be seen at a point where the stucco was still

preserved up to a height of 0.40 m, the diameter gradually decreased

higher up, and it then seems as if the structure had the shape of those

beehive-shaped tall forms, always shown in white τύχβοι, which so often

appear as tombs decorated with taenia in the pictures of the white

lekythoi [1].

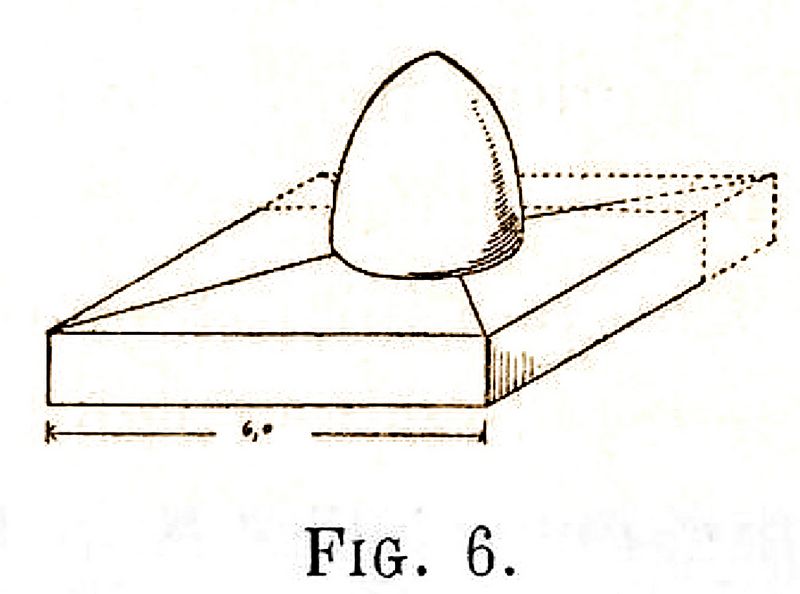

Fig. 6: Behive-shaped tomb.

The present tymbos, however, was certainly of

particularly stately dimensions and particularly solid construction

among its urban contemporaries. It consisted of a loose heap of earth,

which was surrounded by a shell of ring-shaped clay brick layers on the

outer periphery, which gave the structure support and form. Originally

about 3m high, the beehive rose above a wide oblong base surrounded by

four retaining walls of didactic brick. Only one of these walls (F)

touched the circle of the Tymbos, that to the east. It rested on a

foundation of small stones that was not visible, was a mud brick length

d. i. in this case 0.42 m thick and had a height of about 1 m until it

reached the lower stucco edge of the tymbo. Its length was a little

over 6m.

We have only been able to trace part of the side

walls running at right angles to this wall. Nothing was found (p.97) of

a corresponding fourth wall in the west in the immediate vicinity of

the stucco edge; it must then have run at a greater distance than wall

F, perhaps at the same distance as the two side walls. Since there was

no access to the tumulus in either this or F, it must have been in the

assumed fourth wall, and perhaps that is why it was further away from

the edge of the tymbos, in order to have the necessary depth of 1-1.5,

n to win. If local conditions were not decisive for the transfer of the

ascent to this side, one could have taken into account the foundations

of the hero cult when orienting such a sophisticated tombstone, whose

ascent seems to have been primarily from the west. The whole monument

originally shone in the splendor of a brightly shimmering stucco. A

layer of thick yellow stucco was not only found on the outer walls of

the retaining walls, where we found them intact, but also the platform

supported by the walls was covered with it, as was the tymbos itself

and the ground immediately in front of the retaining walls. There were

also traces of a temporary renewal of the stucco.

One can see on

the plan that to the east in front of Wall F there is still a narrow

square wall. However, this did not belong to the first structure of the

Tymbos. Because the yellow plaster of wall F goes through to the corner

g, from which it follows that wall K K was added a little later. Their

continuation had already been discovered during the work in rectangle

A, before slab grave no. 26 was uncovered in the depths below. What

purpose the enlargement should serve we cannot say. Since the

construction of a new tomb did not prompt them, aesthetic

considerations were perhaps decisive, in that the tymbos were not left

standing so hard on the edge, but the platform on this side was also to

be made as wide as on the other three.

We awaited the contents

of the tomb (p.98) (27) with some excitement, the adornment of which

was the extensive complex. They dug down under the round stucco. The

filled rubble in the core of the tymbos contained isolated fragments of

white lekythos, in particular the fragments of a pretty strict lekythos

with the inscription ΛI + AS and with coloring - K A Λ O S bold

painting; the picture represents a girl wrapped in a black himation,

holding a red fruit in one hand and a yellow object (apple?) in the

other. In front of the girl stands a youth in a red cloak, accompanied

by a white dog. Stylistically, the lekythos follows that type treated

by Weisshäupt in these communications (XV p. 40 ).

When you

had penetrated through the embankment, it turned out that the burial

shaft went down into the solid earth below the foundation level of the

mudbrick walls. Its longitudinal axis ran parallel to the side walls of

the tomb monument. The tomb, 2.30 long and 1.14 m wide, was decisive

for the mass of the Tymbos. Of course, to our disappointment, we soon

noticed that the edges of the shaft showed traces of burning pretty

much up to the top, so the prospect of a nice grave find disappeared.

But they dug further down to the level of the groundwater, and when

pumping still did not allow the hard ground to be felt, the Athenian

fire brigade had to help pump out the water until finally, at a depth

of 4m below the lower edge of the stucco round, the ground was reached.

A high layer of charcoal lay above it, in which the only finds

were a tiny shard of a fine black-varnished vessel and the fragments of

an alabastron of fine alabaster. At least the sherd, in connection with

the time when the cemetery was used, provides evidence that the grave

will not be much later than the end of the fourth century BC. A terminus post quem

was already found when the described lekythos was found, which probably

dates back to the first half of the fifth century BC. The graves

discovered on (p.99) the area of the tomb monument, which must have

been laid out before its erection, lead to the same upper time limit.

Four

older graves have been found at this point in the deep digging, each of

which represents a special type, two dipylon graves and two younger

graves. The shaft of a 1.30 m long tomb (IX) descended into the narrow

quadrangular room formed by the extension of the complex. At its

bottom, where the grave narrowed, about six feet below the horizontal

floor of the grave monument, lay the scant remains of a youthful

corpse, the head to the north; the skullcap was only 2mm thick. All

around were 7 cup-like, one-handled Skyphoi, 6 one-handled jugs of the

simplest kind and only partially painted, a kantharos-like cup with two

high pointed handles, sherds of an aryballos with pressed ornaments: so

far everything in the delicate proportions of children's toys. A

dipylon horse made of clay was also included, the head and tail of

which seemed to have been lost in the hands of its little owner, at

least the fractures are old. Of larger proportions is one of the usual

dipylon bowls and a crude saucepan of unpainted brown-red clay, the

outer walls of which were blackened by the smoke of the hearth fire.

A

child's corpse was also found in the second dipylon grave (X). A large

pithos of coarse, unpolished clay, which lay under the round stucco two

paces from the first grave and at a little greater depth than this,

served as her coffin. It was closed by a slab of green slate leaning

against the mouth. The pithos contained only the corpse; Beside it

stood the grave goods, a cooking pot as in the other grave, a large

painted amphora and a small single-handled cup, perhaps also a small

jug, about which we are not entirely sure. (p.100) For illustrations

and more detailed descriptions of the contents of these two graves, see

Section II.

In the ground between these two graves, a little

higher, vertically under wall F, lay one of those coarse amphorae which

the Greek excavators called στάραι. In it we found very fine children's

bones and as an accompaniment a small one-handled jug 0.09 high, two

small Skyphoi with horizontal handles, one 0.045 m in diameter with

black dots, the other a little larger, black varnished and decorated

with a fine dark red stripe , and a 0.09 in diameter box, also

ornamented with black and red stripes.

Finally, the mudbrick

walls, which, as mentioned, served as an extension of the great tomb

monument to the east, ruthlessly cut across a stately tomb (26): it was

a sarcophagus, not hewn out of one block, but of thick ones, in the

manner of the fifth century Porous plates carefully put together so

that two large plates form the floor, two or three plates standing on

top of them enclose the considerably tall tree on each long side and

one plate on the narrow side, and two more plates cover the whole

thing. The upper band of the grave was about 1 m below the floor level

of the grave monument, the grave itself was almost 1 m deep and was

filled with groundwater.

As always in these sarcophagi, the

body was buried; the head was to the south. The grave goods consisted

of about twenty lekythoi and alabastrons. The style of their paintings

was less strict, e.g. already freer, so that one will assume the time

of the grave around 450 BC. With the large number of vessels, it was

noticeable that their paintings all depicted women and Nikes. It is

therefore permissible to identify a woman's grave here (cf. Section IV

below). The tomb that was to be assumed above it had to be removed

before the large monument reached over here.

Footnotes:

1\

[Continue to part 2]

[Return to table of contents]

|

|