|

The Oxyrhynchus Papyri, Vol. 7, edited by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt (London: Egypt Exploration Fund, 1910)

Theological and classical fragments (Nos. 107, 110, 111, 116, 117) [1][2]

_______________________________________________________________

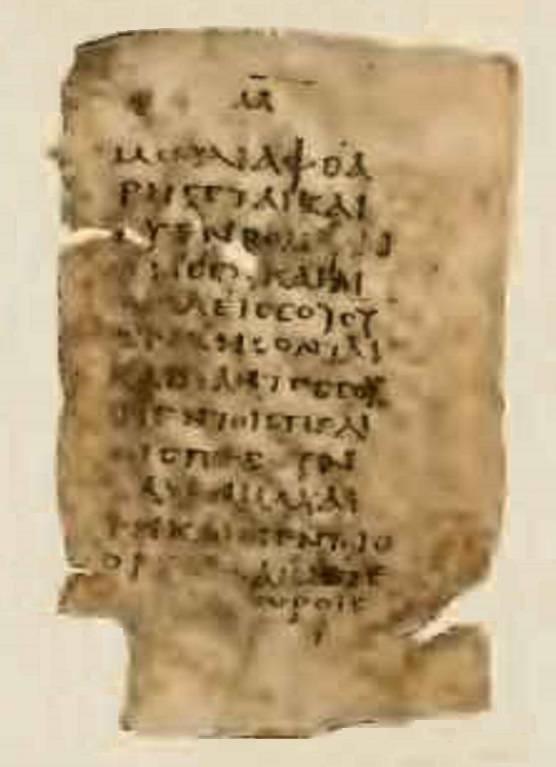

No. 1007. Genesis ii, iii. 516-2 cm. Late 3rd century AD. Plate I (recto). (p.1)

These few verses from the second and third chapters of Genesis are

contained on a fragment of a vellum leaf, which, like the Genesis

papyrus from Oxyrhynchus already published (No. 656), appears to be of

an unusually early date. The text is in double columns, written in a

medium-sized upright uncial which can hardly be later than the end of

the third century, at any rate. A date anterior to the third century AD

has been claimed for two vellum leaves, the Kvretes fragment at Berlin

(Berl. Klassikertexte v. 2. 17), attributed to the first century, and a

fragment in the British Museum of the De Falsa Legatione which Kenyon

assigns to the second (Palaeogr. of Greek Papyri, p. 113). Of the

latter no facsimile has been published, but the age of the former seems

to have been considerably exaggerated, and it may be doubted whether

either of them is to be separated from the present example by a very

wide interval.

Fig.1: Oxy 1007: Genesis II and III fragment (Plate 1)

The columns of No. 1007, which contained about 33 lines, may be

estimated to have measured some 16.5 cm. in height, the leaf having

been of a rather square shape, not much taller than it was broad, like

that of the Kvezes. No stops occur; a short blank space in 1. 25 marks

the close of a chapter. θεός is contracted in the usual way, but

ἄνθρωπος, πατήρ and μήτηρ are written out in full, and the only other

compendium used is a most remarkable abbreviation of the so-called

Tetragrammaton, which in the Septuagint is regularly represented by

κύριος. This abbreviation consists of a doubled Yod, the initial of the

sacred name, written in the shape of a Z with a horizontal stroke

through the middle, the stroke being carried without a break through

both letters ; the same form of Yod is found on coins of the second

century BC .

This compendium exactly corresponds with that employed in Hebrew MSS,

of a later period, ”, which, (p.2) ... occurs in the tenth century and

no doubt goes back to a much earlier epoch. As is well known, it was a

peculiarity of the version of Aquila to write the Tetragrammaton in the

archaic Hebrew letters instead of translating it by κύριος .... A

decided tendency to omit the word κύριος was .... observable in the

early Oxyrhynchus papyrus (No. 656), where in one passage a blank space

was originally left in which the missing word was supplied by a second

hand. Possibly the scribe of that papyrus or its archetype had Hebrew

symbols before him which he did not understand, or the archetype had

been intended to show the Hebrew symbols and they had not been filled

in.

At any rate, in the light of the present example, the question may be

raised whether Origen’s statement (7 Ps. ii) that ‘in the most accurate

copies the (sacred) name is written in Hebrew characters’ was intended

to apply, as is commonly assumed, only to the copies of Aquila’s

version. Apart from the substitution of the Tetragrammaton for κύριος,

the text, though interesting, is not so far as it goes particularly

notable. As usual, it evinces no pronounced affinities with any one of

the chief extant MSS., but agrees here with one, there with another. In

two passages, again (Il. 20 and 28), it sides with some of the cursives

against the earlier MSS. evidence, in one of them (1. 20) having the

support of citations in the New Testament and in Philo.

_______________________________________________________________

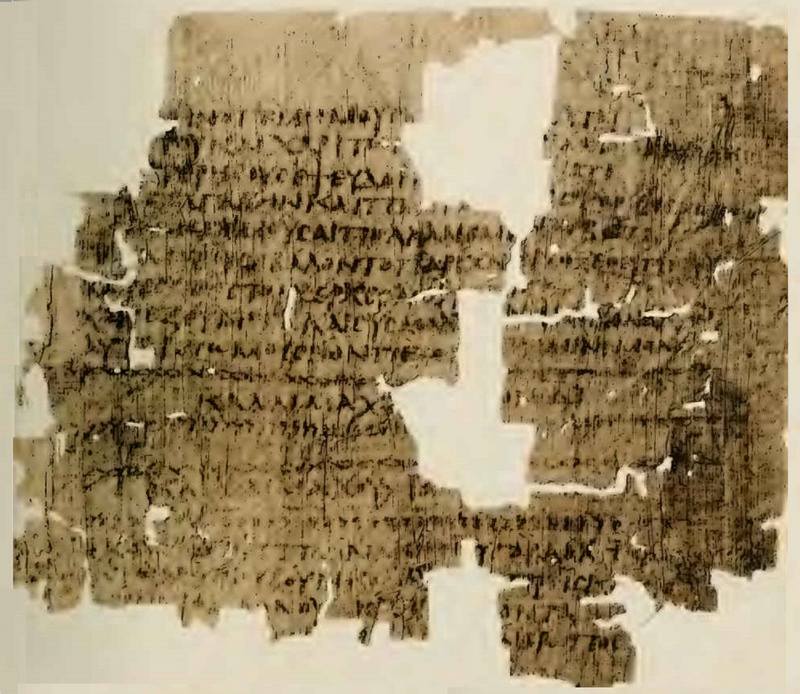

No. 1010. 6 Ezra. 8.4 x 5.6 cm. 4th century AD. Plate I (recto) (p.11)

Oxyrhynchus has already presented us with several fragments in the

original Greek of theological works extant, entirely or in part, only

in translations,—the Apocalypse of Baruch (403), the conclusion of the

Shepherd of Hermas (404), Irenaeus, Contra Haereses (405; cf. P. Oxy.

iv. p. 264), the “εἰς of Peter (849); and there is now to be added to

the list the following specimen of the Greek of 6 Ezra, as modern scholars call the apocalyptic writing which appears in the printed editions of the Vulgate as 4 Ezra, chapters xv—xvi.

Fig.2: Oxy 1010: Ezra book VI (Plate 1)

The sixth book of Ezra was written during a period of persecution, and

James (Texts and Studies, iii. 2, Ὁ. Ixiv) following Gutschmid

(Zettschr. f. wissensch. Theol. iii. 1860) places the date of

composition about AD 268; Weinel, however (Meutest. Apokryphen, p.

312), holds that the time cannot be fixed more definitely than between

AD 120 and 300. An Egyptian origin has often been postulated, and the

discovery of this early fragment at Oxyrhynchus (p.12) though of course

not conclusive, to some extent strengthens that hypothesis. That the

Latin version which alone exists was made from Greek is evident from

the use of such words as vumphea in the passage quoted below; Dr.

Charles believes, on the strength of certain Hebraisms, that some

Jewish document lies behind, but that is a question which does not here

arise. Resemblances to passages in 6 Ezra have been pointed out in

Books xi (ix) and xii (x) of the Sibylline Oracles, but with that

doubtful exception no traces of the document have been recognized in

Greek, and there are very few early references in Latin.

The oldest certain quotations are those of the English writer Gildas,

who lived in the sixth century AD, though it has been supposed that

there is an allusion to xvi. 60 in Ambrose, xxix. Two recensions of the

Latin version are to be distinguished, a French and a Spanish, of which

the principal representatives respectively are the MSS. SA and ΟΜ.....

It is generally considered [these two chapters] were written as

an appendix to 4 Ezra (James, of. c7¢., p. Ixxviii, Weinel, of. cz¢.,

p. 311), and that they never circulated in any other guise or position.

That view is now tenable only on the supposition that this pocket

edition extended to more volumes than one; and it certainly does not

appear at all probable that the form here exhibited would have been

selected for a work on the scale of 4 Ezra and 6 Ezra, which might

easily have been reproduced in a small single volume by the employment

of a somewhat larger page and a more compressed script. The present

discovery therefore rather suggests that the sixth book of Ezra was

originally current independently of the fourth. If the figure 40 is the

number of the leaf, this would point to the existence of some prefatory

matter no longer represented in the Latin. If, on the other hand, the

numeration, as is more likely, refers to the page, the book began in

the same abrupt manner that now characterizes it.

Translation from Greek: (p.14)

"(Thy children) shall die of hunger, and thou shalt fall by the sword;

and thy cities shall be destroyed, and all thy people that are in the

plains shall fall by the sword, and they that are on the mountains and

highlands shall die of hunger and shall eat their own flesh and drink

their own blood in hunger for bread and thirst for water. At first thou

art reduced to misery (?) and again a second time (thou shalt receive

woe)."

New classical texts:

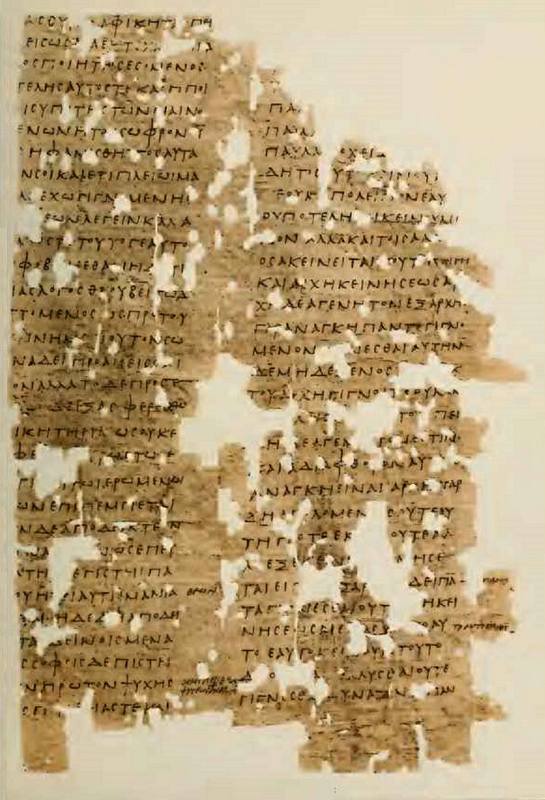

No. 1011. Callimachus [a], Aetia and Iambi. Fol. 130x18 cm. Late 4th c. AD. Plates II and III (Fol. 1 recto, Fol. 2 verso). (p.15)

It might reasonably have been expected that, among the many classical

authors represented by the papyri of Egypt, an Alexandrian poet so

celebrated and so prolific as Callimachus would not fail to finda

prominent place. Hitherto that expectation has not been realized. A

wooden tablet at Vienna has indeed supplied some considerable pieces of

the Hecale (edited by Th. Gomperz, 1893; cf. Wilamowitz, Gdotting.

Nachrichten, 1893, pp. 731-47) ; but the contributions of the papyri

have consisted of a small fragment at Alexandria from the Hymns, and a

scrap of scholia, also on the Hymns, in the Amherst collection (P. Amh,

20).

The deficiency is, however, now amply made good by a discovery

restoring to us substantial pieces of two important works, previously

known only from short and disconnected citations, the Aetia and Iambi;

and by a fortunate chance the new fragments include what was probably

the most popular passage of the Aetia, the famous love story of

Acontius and Cydippe. As now reconstituted the find, which was made in

the winter of 1905-6, consists of seven leaves from a papyrus book,

with a few small pieces still unplaced. One of the leaves is nearly

perfect and a second is only slightly broken; but the others are all

more or less severely damaged. Even where the papyrus is intact,

however, it is often extremely difficult to read, owing partly to the

rubbed and discoloured state of the surface, partly to the fading of

(p.16) the ink, which is of the light brown kind frequently met with in

the Byzantine period. Its ancient readers had already found the

manuscript unsatisfactory in this respect, and letters or words,

occasionally whole lines, have here and there been rewritten. In some

parts of Foll. 6 and 7, moreover, the ink has run badly, and the

papyrus is besides worm-eaten. Where there has been no deterioration

the large and handsome script is of course legible enough. Though

generally sloping it is sometimes erect, and in the size and quality of

the writing, too, some variation is noticeable; an irregular appearance

is also caused by the occasional exaggeration of certain letters, e.g.

x. The coarse down strokes contrast strongly with the light horizontal

lines, which are at times barely distinguishable from the fibres of the

papyrus. o and w are commonly small; «and onarrow. Like that of No.

847, this hand seems to represent a transitional stage between the

sloping oval style, predominant in the 3rd century AD, and the squarer,

heavier type of the 4th and 5th centuries.

Two further considerations assist in the determination of the date: (1)

the semicursive notes and additions which have been occasionally

inserted,

in several cases by the original writer, and of which the age is more easily

estimated than that of the more formal script of the text; (2) the fact that

a small group of documents in the company of which the present papyrus was

discovered (No. 1088 is one of them) was dated about the year AD 400.

On these various grounds the production of this codex is to be placed

in the 4th century AD and, if greater precision is desired, the third

quarter of it is perhaps the likeliest period; Nos. 1008 and 1009,

which were also found along with 1011, appear to belong to about the

same epoch.

Fig.3: Oxy 1011: Callimachus, Aetia, Folio I recto (Plate II)

Accents are not inserted at all systematically, some leaves (Foll. 2,

3, 4) being plentifully supplied, others (Foll. 1, 6, 7) having very

few, while Fol. 5 shows many more on the verso than on the recto. From

the same source come a few marginal signs, the significance of which is

not always evident. The text as it originally stood was not a very

accurate one ; and in spite of the efforts of the (p.17) correctors the

text sometimes remains in an unsatisfactory condition.....

It remains to consider the arrangement and subject-matter of the

fragments. The position in the codex of three out of the seven leaves

is fixed by the pagination. Fol. 1, containing the conclusion of the

story of Acontius and Cydippe, is numbered in the left-hand corner of

the recto 152. It was already known from Callim. Fr. 26 that this elegy was part of the third book of the Aetia,

and according to Schneider, Callimachea, ii. pp. 99 sqq., it stood

early in the book, a view which, as will be seen, suits the data of the

papyrus. The subject of the third book is supposed by Schneider to have

been inventions and inventors, and Cydippe’s history was, he thinks,

introduced in connexion with the art of writing as an illustration of

the injurious results to which that art might lead.

Acontius, a handsome youth, fell in love with the beautiful Cydippe;

and seeing her one day in the temple of Artemis he wrote on a fine

apple the words, ‘By Artemis, 1 will marry Acontius,' and unobserved

rolled this in front of Cydippe. She picked it up and read the

inscription, then threw it aside, and, thinking no more of Acontius,

proceeded to wed another suitor. The preparations were all made when

she suddenly fell ill. Three times the same obstacle to the marriage

occurred, and at last her father betook himself to the oracle of Apollo

and inquired the cause. Apollo informed him of the broken oath and of

the anger of Artemis, and advised him to carry out his daughter’s

undesigned engagement to Acontius. He accepted the advice, the nuptials

were duly celebrated, and Acontius and Cydippe lived in happiness.

Such in brief summary is the story as told with elaborate elegance by

Aristaenetus [b], whose debt to Callimachus has long been

recognized.... The papyrus, which preserves the latter part of the

tale, including the illnesses of Cydippe, the visit of her father to

the oracle, and the happy event (lines 1-52), now enables us to see the

extent of the debt. Aristaenetus follows Callimachus in the main

outlines, and his prose frequently echoes the language of the

poet:... but he omits some details and introduces others of his

own. The relation of the two Ovidian letters between Acontius and

Cydippe .... to the Greek versions is comparatively remote.

This discovery, however, not only displays the beauty of the model of

Aristaenetus ; it reveals the source of Callimachus. He obtained the

story, he says, from Xenomedes [c], an early historian of Ceos, whose

true character now emerges for the first time; cf. line 54 and the

note. The legend, then, was a Cean one; and the fact that a similar

tale is told by Antoninus Liberalis, (p.18) Metamorph. 1, on the authority of Nicander, concerning the Cean heroine Ctesylla, at once becomes more intelligible.

Callimachus proceeds (Il. 56-74) to give a brief summary of the

mythical history of Ceos as narrated by Xenomedes, several details of

which are quite novel; and he expressly credits the historian with a

love of the truth (l. 76).

The last three verses of the page form the transition to another theme.

Between Fol. 1 and Fol. 2 a large gap intervenes. The verso of Fol. 2

contains the conclusion of the following book of the Aetia. In this

epilogue Callimachus, after a reference to the meeting of Hesiod with

the Muses at Hippocrene, an experience which he had in the proém to his

work represented as having happened in a dream also to himself, takes a

formal farewell of poetry, and declares that he will now devote himself

to prose.

The poet must then at this time have had in view a large and important

prose work; and it is natural to suppose that he was here alluding to

his Πίνακες, a kind of literary encyclopaedia, which is said by Suidas

to have extended to 120 books and must have occupied the author during

a long period. But the Πίνακες were certainly written at Alexandria ;

and it would hence follow that the Aetia were not completed, as held by

Schneider, of. c7z. ii. p. 40, at Cyrene, and the choice would lie

between the view of Merkel (Apollon. Rhod. p. xxi), that these poems,

though begun were not published in youth, and that of Hecker, Com.

Ca/lim. p. τό, that they were the product of the poet’s maturity. At

any rate the present passage is in thorough accordance with the view of

Wilamowitz (Texigesch. d. gr. Bukoliker, pp. 173-4, cf. Gotting. Nachr.

1893, pp. 745-6) that the poetical activity of Callimachus is to be

assigned to the prior part of his career, and that his appointment at

the Alexandrian library turned his energies into another channel.

Fig.4: Oxy 1011: Callimachus, Folio II verso (Plate III)

Below these final verses is inscribed the title of the foregoing book,

‘The fourth Book of the Aetia of Callimachus.’ From the fact that no

number beyond four had been mentioned in the citations from this work,

the inference had been drawn that it did not include more than four

books; and this is now definitely confirmed by the papyrus. ....

Suidas relates that Marianus, who flourished in the fifth century,

produced a μετάφρασις of the Hecale, Hymns, Aetia, and Epigrams of

Callimachus in 6,810 iambic verses. Marianus is hardly likely to have

effected a considerable reduction in the number of the lines; the

tendency would rather be in the opposite direction. But the extant

hymns and genuine epigrams of Callimachus amount to 1,400 lines, and

the Hecale appears to have been a lengthy poem; therefore, if the four

books of the Aetia averaged some 1,500 lines, a much larger total than

6,810 iambics would be expected. If on the other hand the alternative

view be adopted, that the foliation of this MS. referred to pages, and

consequently the foregoing estimate of leaves and lines be divided by

two, the difficulties disappear. Seven or eight hundred lines is the

normal compass of a book, and the scope of Marianus’ metaphrase, with

some allowance for hymns and epigrams no longer extant, becomes more

natural.

The Iambi open with a general prologue, extending to about 30 lines, of

which the first three and a half had already been correctly

reconstructed from (p.20) scattered citations. At 1]. 103 begins the

story of Bathycles’ cup, which was to be given to the wisest man and

went the round of the seven sages until it came a second time to

Thales, by whom it was dedicated to Apollo of Didyma: cf. Diog. Laert.

i. 28 ...

The sixteen verses on Fol. 2 are much obscured by mutilation, but Fol.

3 verso is in rather better case. Thales is discovered drawing

geometrical figures by Bathycles’ son, who offers him the cup. The

first two verses and the gist of part of the following passage were

previously known from Diogenes Laertius and Diodorus Excerpt. Vat., by

means of which attempts had been made at restoration (Fr. 83 a) with,

as is now seen, indifferent success....

This story is referred in ll. 171-3, a passage already known as an

adespoton, to Aesop (cf. the citation in 1. 54 of Xenomedes), but is

not found in the extant collection of Aesopian fables or in those of

Babrius. The rest of the verso and the recto is severely damaged, and

there is little that is intelligible until in 1. 211 the narrative of

the dispute between the two trees is begun. If, as may well be the

case, the preceding lines of the recto all belong to the preface of

this, the fable would appear to have been narrated by one of the

persons whose meeting is described in Il. 192 sqq. The first two and a

half verses of the story itself were already extant (Fr. 93a), but

nothing was known concerning the nature of the quarrel, or of

Callimachus’ treatment of it in the poem of which a substantial portion

is now happily recovered in Fol. 5.

In rhetorical speeches the rivals expatiate in turn upon their

own respective merits and advantages, the laurel dwelling upon its

ritualistic and ceremonial uses, and taunting the olive with the

indignity of association with corpses (ll. 218-239).

To this the olive replies at length (lines 242 sqq.), priding itself on

assisting to honour the dead, and, with regard to the pretensions of

the laurel, pointing out that the olive-branch was the prize of victory

at Olympia, which ranked before Delphi. The olive proceeds (lines 260

sqq.) to claim superiority on the ground, first, of a more illustrious

origin, secondly, of its serviceable qualities, and thirdly, of being

the emblem of the suppliant. At ll. 291-6 another tree intervenes in

the interests of peace, but with the result of making the laurel, which

is getting the worst of the argument, the more angry, and the would-be

peacemaker only meets with abuse.

Here the papyrus fails us and, since the next leaf is missing, we cannot tell how the quarrel was brought to a termination.

It is, however, something to learn that Callimachus, like other

iambographers, wrote in trochaic tetrameters (trochaic pentameters are

exemplified in Fr. 115); and the remains are sufficient to show that

his use of the measure was marked by an unexpected freedom. ....

Callimachus thus allows himself the same licence in this respect as the

comedians. ....

For the sake of clearness a brief summary of the disposition and contents of the leaves may here be added :

— Fol. 1 verso and recto (pp. 151-2) = dez. iii, story of Cydippe.

Fol. 2 verso (p. 185?) = “4162. iv, conclusion, and /amé., prologue.

recto (p. 186?) = conclusion of prologue, and story of Bathycles (Lamb.

1).

Fol. 3 verso (p. 187) = story of Bathycles continued. recto (p. 188) : subject doubtful (Zam. 2).

Fol. 4 verso |p. 189] = story of the reign of Saturn (continuation of

/amé. 2 ?), recto [p. 190| = story of dispute between laurel and olive

(amd. 3).

Fol. 5 verso and recto (pp. 191-2) = dispute between laurel and olive con-tinued.

Fol. 6 verso and recto [pp. 195-6 or 197-8?] = ἃ piece relating to poetical composition, especially tragedy (Jam. 4).

Fol. 7 recto and verso [pp. 201-2 Ὁ] = trochaic poem (amb. 5).

In the reconstruction and interpretation of this difficult text I have

received invaluable assistance from Professor U. von

Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, to whom is due in no slight degree such

success as may have been attained. Many restorations and comments will

be found expressly attributed to him in the notes below; but the

frequency of these references is by no means the measure of my great

obligations. The proofsheets were also seen by Professor Gilbert

Murray, whom I have to thank for a number of acute suggestions and

criticisms.

Text of Aetia

Translation from Greek: (p.60)

lines 1-9

“...and already the maid had been couched with the youth in accord with

the custom bidding the affianced bride forthwith rest in a pre-nuptial

sleep with her all-favoured suitor. For they say that once Hera [1] —’

Cease, dog, cease: reckless heart, thou wilt sing what it is not lawful

for thee to speak of! Lucky indeed for thee that thou hast never seen

the mysteries of the dread goddess, or thou hadst e’en begun to blurt

out the tale of them. Verily much knowledge is a grievous ill for one

who controls not his tongue; how truly is he a child possessed of a

knife.’

notes:

1. In Aristaenetus i. 10 [b] the description of the sickness with which

Cydippe was seized is immediately preceded by a long speech placed in

the mouth of Acontius; whois apparently expressing his regret that

Cydippe had not immediately followed up her (unintentional) declaration

that she would marry him after the custom of the maidens of her own

island, who copied the example of Hera.

translation from Greek: (p.60-61)

10-49. ‘In the morning the oxen [2] were about to chafe their spirit in

the water, having before them the evening’s keen blade, when she was

seized by a dread pallor, seized by the sickness that we send out into

the wild goats [3], and falsely call sacred ; this it was that then in

grievous wise wasted the girl to her very bones. A second time were the

couches spread; (p.61) a second time the maiden lay ill seven months of

a quartan fever. A third time they bethought themselves of the

marriage: again for the third time a fearful chill laid hold of

Cydippe. For a fourth time her father did not tarry, but set off to

Apollo of Delphi, who in the night spake this oracle: “A dread oath by

Artemis breaks off the maiden’s marriage with Lygdamis [4]. My sister

was not troubling Tenos, nor plaiting rushes [5] in Amyclae’s temple,

nor, fresh from the chase, washing away her stains in the stream of

Parthenius [6], but was sojourning at Delos, when your child vowed that

she would have Acontius and none other for her husband ...; but if you

will take me for your adviser you will perform all your daughter’s

pledges [7]. For I say that you will not be mixing silver with lead,

but in accepting Acontius will be mingling electrum with shining gold.

You the father-in-law are of the stock of Codrus, while your Cean son

is priest of the rites of Aristaeus [8] Bringer of Rain, one whose duty

it is to soften on the hill-top the fierceness of the rising Maera, and

to ask of Zeus the wind by which the thronging quails [9] are stricken

in the hempen nets.” Thus spake the god: and the other returned to

Naxos and questioned the maid herself, but she hid all the tale in

silence. So he voyaged forth: it remained to fetch thee, Acontius, to

his own Dionysias. And faith was kept with the goddess, and the maid’s

fellows forthwith sang their comrade’s bridal songs which were no more

delayed. Methinks, Acontius, thou wouldst then have taken for the

maiden girdle which thou didst touch that night neither the foot of

Iphicles speeding over the corn-tops nor the wealth of Midas of

Celaenae, and all who are not ignorant of the grievous god would

testify to my judgement.’

notes:

2. It was already the morning of the day on which Cydippe’s

marriage was to be celebrated when the sickness overtook her. The

oxen were to exhaust some of their high spirit in a morning bath, in

order to come clean and quiet to the evening sacrifice.

3. The supposed connexion with goats comes out in the

Hippocratean treatise περὶ ἱερᾶς νούσου" ad init. where notice is taken

of the popular belief that it was harmful to eat goats’ flesh and to

wear or lie upon goat-skins; cf. also the references there to the

καθαρμοὶ καὶ ἐπαοιδαί by which a cure was sought.

.

4. The Naxian rival of Acontius is given a well-known Naxian

name. A cult of Artemis at Tenos is attested by the name of the month

᾿Αρτεμισιών, C.I.G, 2338; at Amyclae we hear from Pausanias iii. 18.9

of a statue of Artemis Λευκοφρυηνή carved by Bathycles of Magnesia. The

present passage points to a common cult of Artemis and Apollo in the

great shrine of Amyclae, such as is frequently found elsewhere. Artemis

was prominent in Laconia.

5. Reeds or rushes would be appropriate to Artemis as a river goddess.

6. Parthenius was also an older name of the river Imbrasus in Samos according to Callimachus.

7. The commencement of this verse is a crux. Some reference to the stratagem of Acontius would be expected; cf. Aristaenetus.

8. The meaning here doubtless is that Acontius was the priest of Aristaeus- Icmius, which showed his high lineage.

9. It is in March that the quails begin to migrate north across the

Mediterranean. But the north wind which brought the birds was the wind

which later on cooled the summer heats, and there is no reason to

suspect the poet of having confused the ἐτησίαι and the ὀρνιθίαι.

translation from Greek: (p.65)

50-79. ‘From that marriage a great name was to spring: for thy line the

Acontiadae still dwells, Cean, numerous and honoured at Iulis; and this

desire of thine we heard from old Xenomedes [10], who once lay up a

memorial of the whole island’s lore, beginning with how it was taken

for an abode by the Corycian nymphs whom a mighty lion [11] drove from

Parnassus, wherefore they named it Hydrussa; and how Ciro . . . dwelt

at Caryae [12], and how the Carians [13] and Leleges abode in the

island, whose offerings Zeus, god of the battle-cry, ever receives to

the trumpets’ sound, and then Ceos [14], son of Phoebus and Melia,

caused it to be called by another name; and the tale of insolence and

death by lightning, and the sorcerers the Telchines, and Demonax who in

his folly recked not of the blessed gods the ancient put in his

tablets, and the aged Macelo, mother of Dexithea, whom alone the

immortals left unscathed when for its wicked insolence they laid the

island waste; and how of its four cities Megacles founded Carthaea, and

Eupylus, son of the demigod Chryso, the fair-founted citadel of Iulis,

yea and Acae . . Poeéssa, seat of the long-tressed Graces, and

Aphrastus Coresus’ town, and joined with them the old man, friend of

truth, told, Cean, of thy sore love; whence came the maiden’s story to

my muse. I will not then now sing of the habitation of the cities... .’

notes: (p.66)

10. This reference by the poet to his authority is highly interesting

and also provides some historical information of importance. Xenomedes

[c] is occasionally cited by grammarians .... but only in one passage

is he more fully specified, Dion. Hal. De Thucyd. 5, where Xenomedes

stands in a list of local historians prior to the Peloponnesian

war. It is now evident that Χῖος should there be emended ... to

Κεῖος, and that Xenomedes is to be recognized as the Cean writer who

was no doubt among the sources of Aristotle and, indirectly, of

Heraclides [d] in their accounts of the history and institutions of

Ceos. Several points of contact with lines 56-63 are to be found in the

excerpts of Heraclides ....

11. According to the Heraclides excerpt quoted in note 10 above, the

lion was the cause of the departure of the nymphs, not of their

arrival. A colossal lion close to a spring of water (cf. 1. 72

εὔκρηνον) is still one of the features of the site of Julis.

12. Who it was who lived at Caryae and what this has to do with Cean

tradition remains a problem. Besides the well-known Laconian Caryae we

hear of places so called only in Arcadia and Lycia, and there is no

evident link between any of these and Ceos. .... Carystus, son of

Chiron, was the reputed founder of Carystus in Euboea, and it is

noticeable that in the Heraclides excerpt cited above that town

is mentioned.

13. Herodotus i. 171 attributes certain inventions in armour to the

Carians, whose warlike proclivities are also indicated by the tradition

that they were the first μισθοφόροι; but they do not appear to be

elsewhere specially connected with σάλπιγγες, the introduction of which

was claimed by the neighbouring Lydians. The custom referred to by

Callimachus belongs not to Ceos but to the Carians proper, whose Ζεὺς

Στράτιος (Hdt. v. 119, &c.) is here meant by Ζεὺς ᾿Αλαλάξιος, (p.67)

14. Ceos is called the son of Apollo and Rhodoéssa in Etym. Magn. 504.

53. 64-9. ... In three respects Ovid and his scholia are at variance

with the version of the legend here given by Callimachus. .... the

ancient commentators thereon represent Macelo not as Dexithea’s mother,

but as an elder sister who was slain on account of the guilt of her

husband, while Dexithea and other sisters were preserved ; moreover,

the name of the sisters’ father, the chief of the Telchines, is given

as Damo, who is obviously to be identified with the Demonax.

Text of Iambi:

translation from Greek: (p.75)

lines 218-239."... the left white as a snake’s belly, the other, which

is oft uncovered, -burnt by the sun. What house is there where I am not

at the door-post? What seer, what offerer of sacrifice does not take me

with him? Yea, and the priestess of Pytho has her seat in laurel, of

laurel she sings, of laurel makes her couch. O foolish olive, did not

Branchus save the sons of the Jonians, when Phoebus was angry with

them, by striking them with laurel [1] and saying twice or thrice ...?

I go to feasts and to the Pythian choral dance, I am made a prize of

victory, and the Dorians cut me on the hill-tops at Tempe and carry me

to Delphi whene’er the rites of Apollo are celebrated. O foolish olive,

I am acquainted with no hurt, nor know I the path of the bier-carrier,

for I am pure, nor do men trample me, for I am sacred; but with you

whenever they are about to burn a corpse or lay it out for burial they

crown themselves and also duly place you beneath the sides of the

lifeless body ”.’

notes:

1. The allusion here is to the Delphic theoria sent every ninth

year to Tempe, whence a laurel branch was carried back by a δαφνηφόρος

παῖς. This solemnity commemorated the purification of Apollo at Tempe

... after killing the Python ; see Steph. Byz. p. 223. 12,

Plutarch, Ae/. Gr. 12 (293), Miiller, Dordans ii. 1. 2.

Translation from Greek: (p.76)

240-59. "Thus boasting spake she; but nothing daunted the producer of

oil repelled her: 'O laurel, utterly barren of that which I bear, you

have sung like a swan at the end I help to carry to burial the men whom

Ares slays and (am laid on the bier) of the heroes who (perish nobly)

[2]; and when a white-haired grandmother or an aged Tithonus is borne

to the grave by their children, I attend them and am laid upon the

ground. I.. more than you for those who bring you from Tempe; _ nay,

even in that matter of which you spoke, am I not also as a prize

superior to you, for where is the greater festival, at Olympia or at

Delphi? Yes, silence is best! I indeed say nought of you that is either

good or ill, but the birds have long been sitting among my leaves

unwontedly chattering thus' ”. [3]

notes:

2. W-M thinks that the point of this allusion to the κύκνειον μέλος is

the mention by the laurel of funerals, which is accepted as a bad omen.

3. Ἰ neither praise nor blame ; it is the birds in my branches

which chatter thus.’ The olive humourously attributes to the birds its

unflattering remarks.

Translation from Greek: (p.78)

260-80. ‘Who found the laurel? the earth (produced it) just like the

ilex, the oak, the galingale, or other timber. Who found the olive?

Pallas, when she contended for Acte with him who dwells amid the

seaweed, and the man of old who in the lower parts was a snake gave

judgement. That is one fall for the laurel. Who of the immortals

honours the olive, who the laurel? Apollo the laurel, Pallas her

discovery the olive. In this they are even, for I distinguish not

between gods. What is the laurel’s fruit? For what shall I use it?

Neither eat it nor drink it nor anoint yourself with it! But that of

the olive pleases in many ways: it is a morsel for food. .., and with

it as an unguent one may dive as deep as Theseus(?) [4]. A second fall

I set down to the laurel. Whose is the leaf that suppliants hold

forward? The olive’s: for the third and last time is the laurel thrown.

Oh, the tireless ones! how they chatter. Shameless crow, does not your

beak ache? Whose is the trunk preserved by the Delians? The olive’s,

which gave a seat to Leto.’

notes:

4. The general sense evidently is that the produce of the olive is good both as

food and as an unguent; the employment of oil as an unguent is apparently traced back to Theseus.

_______________________________________________________________

Extant Classical Authors

No. 1016. Plato [e], Phaedrus. 2857-5 cm. 3rd century AD. Plate V (Cols. v-vi). (p.115)

Six columns in very fair preservation, containing the proem of the Phaedrus

(pp. 227a-230e). A coronis is placed at the bottom of the last column,

and a broad margin follows, which shows that the dialogue was not

continued on this sheet ; either, therefore, it was for some reason

left incomplete or a fresh roll was begun.

As with so many of the literary papyri belonging

to the first large find of 1906, from which both Nos. 1016 and 1017 are

derived, this text is on the verso of a cursive document, a register of

landownérs, part of which is printed later on in this volume (No.

1044). The document was drawn up in the fourteenth year of an unnamed

emperor, no doubt either Marcus Aurelius (AD 173-4) or Septimius

Severus (AD 205-6).

Fig.5: Oxy 1016: Plato, Phaedra, cols. 5-6 (Plate V)

A date near the commencement or in the earlier decades of the 3rd

century AD is therefore indicated for the MS. of the Phaedrus, and this

is the period which the hand itself would naturally suggest. It is a

medium-sized uncial of the oval type, but upright, and written in a

rather free and flowing style. .... (p.116) The text is not

uninteresting, showing a number of small variations from the mediaeval

MSS. No doubt the scribe was liable to make mistakes (cf. Il. 40, 85,

154, 187) and sometimes seems to have had a difficulty in reading his

archetype (cf. notes on 1]. 160 and 229). On the other hand good

readings occur which have hitherto rested either on inferior evidence

or modern conjecture; .... These lend a certain colour to the variants

the value of which is more questionable. As between the two principal

MSS., the Bodleianus (B) and Marcianus (T), the papyrus shows, as

usual, little preference, agreeing first with one and then with the

other. The appended collation is based on Burnet’s Oxford edition, of

which B and T are the foundation; occasional references to other MSS.

are taken from the edition of Bekker.

_______________________________________________________________

No. 1017. Plato, Phaedrus. Height 27.5 cm. Late 2nd or early 3rd c. AD. Plate VI (Cols. xix—xx). (p.127)

The following remains of a fine copy of the Phaedrus

extend from p. 238c to p. 251b, with considerable lacunae, a gap of as

much as eleven columns occurring after Col. vii. This text and No.1016

were found together, but they are two quite distinct manuscripts, and

differ markedly both in the quality of the materials and the character

of the hands.

Fig.6: Oxy 1017: Plato, Phaedra, cols. 19-20 (Plate VI).

This MS. is probably rather earlier in date than No. 1016, and may go

back to the end of the 2nd century AD. The text is on the whole

accurate and good, and the double readings, which have been referred to

above, give it a particular interest.... The papyrus shows its good

(p.128) quality by frequently preserving the superior reading when one

of the two chief authorities, Bodleianus (B) and Marcianus (T),

goes astray, sometimes (e. g. xxi. 4, xxii. 13) against them both. As

in the commentary on No. 1016, it is to the evidence of those two MSS.,

as given by Burnet, that the collation appended below is for the most

part confined; some additional information has been supplied from

Bekker’s edition.

Footnotes:

1. [Editor's Note:] The original textual commentaries and notes provided by Grenfell and Hunt on

passages in Greek, and on some bibliographic references, have sometimes been abbreviated or omitted, if not essential to

understanding the content of the papyri documents. Any such omissions

are marked with "....", and any added words needed for clarity are

placed between brackets [ ]. These elisions are separate from those

used by Grenfell and Hunt in the translated text, which have not been

altered.

2. [Editor's Note:] References to all other papyri from the Oxyrhynchus

collections are given with their sequential number as "No. xx".

Abbreviations to other papyri collections and standard historical

references used by Grenfell and Hunt include the following:

Archiv.= Archiv fur Papyrusforschung.

B.G.U. = Aeg. Urkunden aus den K. Museum zu Berlin, Griechische Urkunden.

C.I.G. = Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum

C.I.L. = Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

Cod. Just.= Codex Justianus

Cod. Theod.= Codex Theodosianus

C.P.R. = Corpus Papyrorum Raineri, by C. Wessely.

Marcellinus =The late Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus.

P. Amh. = The Amherst Papyri (Greek), Vols. I-II, by B.P.Grenfell and A.S.Hunt.

P. Brit.Mus. = Greek papyri in the British Museum, vol.I-II by F.G. Kenyon.

P. Cairo = Catalog of the Greek Papyri in the Cairo Museum,by Grenfell & Hunt.

P.

Grenf. = Greek Papyri, Ser. 1 by B.P. Grenfell, and Ser. II by Grenfell and Hunt

P. Hibeh = The Hibeh Papyri by B.P Grenfell and A.S. Hunt

P. Leipzig = Griechische Urkunden der Papyrussammlung zu Leipzig by I Mitteis.

P. Leyden = Papyri Graeci Musei Antiquarii Lugduni-Batavi, by C. Leemans.

P. Tebt. = The Tebtunis Papyri, by B.P. Grenfell, A.S. Hunt, et al.

Perseus = the satirical ancient Roman playwright Perseus.

Wilcken, Ost. = Griechische Ostraka, by U. Wilcken.

a. [Editor's Note:] Callimachus (ca.310 – 240 BC) was an ancient Greek poet

who wrote over 800 literary works in a wide variety

of genres. He was born in Cyrene, a Greek city on the coast of

modern-day Libya.

During the 280s, Callimachus is thought to have studied under the

philosopher Praxiphanes and the grammarian Hermocrates at Alexandria, According to the the Suda, a 10th-century AD Byzantine encyclopaedia, Callimachus then entered into the patronage of

the Ptolemies, the Greek ruling dynasty of Egypt, and was employed at

the Library of Alexandria. His career coincided

with the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, who became sole ruler of

Egypt in 283 BC, and married

his second wife, Arsinoe II, who was also his sister, sometime between

276 and 273 BC. Callimachus wrote poems on the occasion of their

marriage. The composition of Books

1 and 2 of the Aetia is dated to the 270s. The popularity of the Aetia is indicated by

the large number of fragmentary papyrus copies that have survived.

b. [Editor's note:] Aristaenetus was an

ancient Greek epistolographer who flourished in the 5th or 6th century

AD. Under his name, two books of love stories, in the form of letters,

are extant; the subjects are borrowed from the erotic elegies of such

Alexandrian writers as Callimachus, and the language is a patchwork of

phrases from Plato, Lucian, Alciphron and others.

c. [Editor's note:] Xenomedes of Keos (5th c. BC) was a historian who wrote about the mythic genealogy and history of

Ceos. The references from Callimachus are a main source of information about this otherwise little known historian.

d. [Editor's note:] Heraclides Lembus was a 2nd c. BC Greek historian

and philosophical writer whose works only survive in fragments quoted

in later authors. The Suda mentions a

Heraclides of Oxyrhynchus, He lived during the

reign of Ptolemy VI Philometor and worked for the Ptolemaic administration, with Agatharchides of Cnidus as his secretary. He is said to have negotiated the treaty that ended Antiochus IV's invasion of Egypt in 169 BC.

e. [Editor's note:] Plato (424 – 348 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher who founded the Academy in Athens. Along with his teacher, Socrates, and student Aristotle,

Plato is a central figure in the history of philosophy, whose entire body of work

is believed to have survived intact for over 2,400 years. He was an innovator of the written dialogue and dialectic forms in philosophy. His dialogue Phaedrus, composed

in about 370 BC, is between Socrates and Phaedrus, who appears in

several dialogues. The discussion revolves around the art of rhetoric

and how it should be practiced, and covers diverse subjects including

reincarnation, erotic love, and the nature of the human soul.

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

|