|

Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia, by Richard Lepsius. Volume I, Lower Egypt and Memphis.

(Original publication of plates 1849-1859; Explanatory text from

the 1897 German edition, edited by Kurt Sethe and Eduard Naville).

Introduction

PREFACE FROM THE PUBLISHER, by Edouard Naville (p.v.)

Half

a century has passed since the scholar who could even then be called

the renovator of Egyptian studies, Richard Lepsius, returned to Berlin

after more than three years in Egypt, from where he brought back

considerable scientific treasure. During these fifty years many

disciples have arisen; Egyptology which, originally, seemed to be the

monopoly of a few minds curious about new discoveries in philology and

history, has recruited numerous adherents in almost all countries: the

science has developed so widely and has grown so much, so quickly that

we are sometimes inclined to forget the difficulties that the first

pioneers who cleared this vast and mysterious domain had to overcome.

Because on many points they have been surpassed, we are inclined not to

give their works the importance they had at the time they appeared.

Where we go back to the early days of Egyptology, in 1822 the genius of

Champollion opened the door that had been closed for nearly fifteen

hundred years. But when ten years later the pen had fallen from his

dying hand, no one came to retrieve it.

Fig.1: Jean-Pierre

Champollion (1790-1832) was painted by Cogniet in 1822, the same year

that Champollion sent the French Academy the famous "Lettre a M. Dacier

relative à l'alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonetiques," announcing his

discovery of the syllabary used in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The

result of his conscientious and close investigation is recorded in his

"Letter to Professor H. Rosellini on the hieroglyphic alphabet"

published in Rome in 1837. This work, however brief it may be. was

epochal. This is where the renaissance of Egyptological studies begins.

It

is like the crowning of the building whose walls Champollion had

raised. For the first time the master's discovery was put under the

sieve of a rigorous method. Lepsius definitively established the

principle laid down by his glorious predecessor. He corrects here,

removes what could not withstand the test of his close criticism; but

the reality of the discovery is put out of the question, and moreover

Lepsius shows the way to advance in the decipherment. He was living

proof of the goodness of his method, which soon brought him significant

success; the works he published in the years that followed marked great

progress on those of Champollion and Rosellini.

To this research

which he pursued with ardor in Paris, Turin, and Rome, there was a

necessary complement, a trip to Egypt. to the country whose language

and history he was reconstructing. He had to be able to apply his

method on site, and verify his discoveries in a wider field than that

of the museums of Europe. Thanks to the fact that his two protectors,

Bunsen and A. de Humboldt, found the most generous support with King

Frederick William IV. whose high intelligence was interested in the

studies of the young scholar, Lepsius left in the fall of 1842 at the

head of an expedition, whose personnel he had chosen himself was likely

to ensure success. Let us cite among his collaborators two of them who

appear in this publication, the young architect Erbkam, responsible

more specifically for drawing up plans and doing research and drawings

concerning architecture, and Max Weidenbach, one of the two equally

skilled brothers, one of whom copied and reproduced Egyptian

inscriptions, and his brother Ernst, an artist later attached to the Berlin Museum, drew all

the latest works of Lepsius [a].

(p.vi) Like Champollion. Lepsius

kept the scholarly world informed of the progress of his journey and of

the discoveries which marked it in his letters later collected in a

volume: "Briefe aus Aegypten, Aethiopien und der Halbinsel des Sinai" [Letters from Egypt, Ethiopia and the Sinai Peninsula,

Berlin 1852]; We follow the traveler in all the stages he made in the

Nile valley and as far as Sudan; we witness the life of the expedition

and the episodes of the journey; but what is especially interesting in

these letters is what we can call the description of the scientific

landscape, all the new facts which constantly present themselves to his

amazed eyes of these monuments as admirable as they are varied.

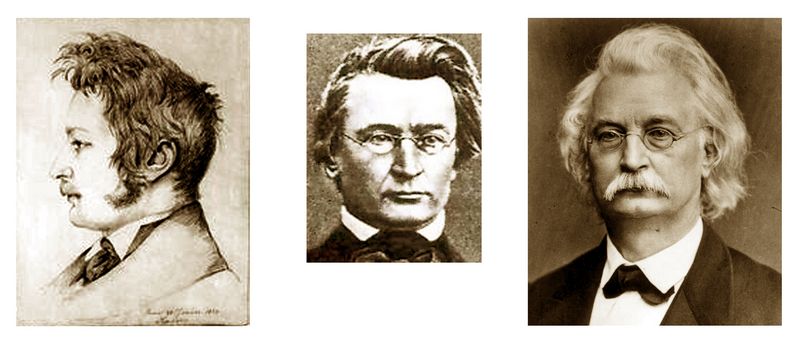

Fig.2:

Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-1884), at three periods of his life,

starting at left as a young researcher and university professor in the 1840s, when he

led the expedition to Egypt.

These

letters also give us an overview of all the riches that he gathered

during the three years of his journey, whether in monuments intended

for the Berlin Museum, or in drawings, casts, stampings, reproductions

of all kinds that 'he intended to publish immediately after his return.

Apart from this abundant harvest which was rather the fruit of the work

of the collaborators under his direction, there was the result of his

own work, a detailed diary which he wrote from the beginning to the end

of his journey. One of the members of the expedition, Max Weidenbach [a],

described to us one day the ardor with which, upon seeing a new

monument, Lepsius began to study it in detail, striving to understand

it. understand the plan and the destination, looking for all the

interesting particularities, and especially what related to history,

his main concern.

The results of these studies and the

description of all the monuments that he had before his eyes were

recorded in this journal which, in Lepsius's mind, was to be the main

source from which he would constantly return to draw, and which he

would use it above all for the publication of the documents that the

expedition had collected. If one thinks that the writing of this

journal came in addition to the concerns of all kinds that led to the

direction of a numerous expedition. monitoring and revising the work of

his various collaborators, one can only admire the power of work that

this supposes, and one is surprised that Lepsius was able to sustain

such intense activity for three years through the fatigue of the travel

and under the heat of the climate.

At the beginning of 1846 he

was back in Berlin where he had preceded the collection of monuments he

had found in his excavations, and the enormous harvest of drawings and

stampings he had collected on the banks of the Nile. He immediately set

about publishing his riches. King Frederic William IV., delighted with

the success of the enterprise due to his royal generosity, immediately

granted a sum for the publication, the form and appearance of which he

prescribed. It was according to the formal desire expressed by His

Majesty that the "Denkmaler aus Aegypten und Nubien" [Monuments from Egypt and Nubia] became

a luxury work of an exceptionally large format, and which was to become

epochal. both by the beauty of the execution and by the value of the

content. In 1856 the final delivery and the last of the 894 plates

appeared. Lepsius had monitored the publication very closely down to

the smallest details, and although we do not have the work of his hand,

the conception of the book. the plan adopted belongs entirely to him.

The chronological order on which it is based is consistent with the

solutions he had given to several doubtful questions in the series of

Egyptian dynasties.

Most of the works of Lepsius which appeared either during the publication of Denkmaler

or after, touch in some way on this great work, or are based on

documents contained therein. Lepsius considered these works as

preliminary comments intended to shed light on this or that part of the

explanatory text. He announced this text in 1849 when the first plates

appeared. It was to have an approximate capacity of 80 to 100 sheets in

4to to which additional plates of the same format would be added. For

the first part of Denkmaler it would include a geographical description of all the localities in Egypt where monuments were located.

For

the following parts the author restricted his framework and made his

reservations in advance: "The purpose of the explanation of the

remaining sections is by no means an exhaustive antiquarian treatment

of the depictions given, nor a complete translation of the

inscriptions. Every expert knows that for the most part this is not yet

possible, and that a philological-critical explanation of even that

part of the inscriptions. which already allowed such a thing, but could

only be delivered in many volumes and with the help of extensive and

very specific investigations." And he continues by saying that we must

limit ourselves for the moment to perfectly certain explanations and to

the clear and correct publication of the texts by highlighting what

they present that is remarkable.

(p.vii) Although he had reduced

it to these modest proportions, Lepsius never decided to write down

this explanatory text, and for those who have known him closely this is

not surprising. He had conceived it in an ideal form that was too lofty

and too ambitious. Let us not forget that then we were still very far

from the point that science has reached today. In terms of translation

we only tried to interpret pieces of a certain extent and no longer

fragments of sentences. Anyone who at this time would have undertaken

to write a text to the Denkmaler

saw a host of questions arise before him, some of which have not yet

been resolved. and before which he should have stopped otherwise he

would only give hypothetical or poorly established solutions. These

conditions displeased the methodical and precise mind of Lepsius. As

much as he liked to take a circumscribed subject and explore it

thoroughly, taking advantage of all the resources that could shed light

on the obscure points, he also felt reluctant to undertake a task that

was too vast, poorly defined, and where by the force of circumstances

he would have had to leave a lot of vagueness, and a lot of obscurities

that it was not possible for him to dissipate.

He could not be

satisfied with a text which necessarily could only be an outline, only

an essay, and which would not get to the bottom of the questions. This

enterprise, before which he hesitated at the beginning, became more

difficult from year to year. As Egyptology took off in France, England

and Germany, a considerable number of works arose which had to be taken

into account; the ideal that Lepsius had formed was increasingly less

easy to realize; so it soon became ever more probable that this text

would not appear; and when the weight of years, aggravated by family

trials, made itself felt on his robust constitution, he had to give it

up entirely. On July 10, 1884, Lepsius left this world without even

having begun the writing of this text which seemed to be the great work

of his life; he took with him a whole treasure of knowledge and

information which should have appeared in the work and which was not

made public anywhere.

But there remained of him what in his

intentions should have been the basis of this explanatory text: his

diary. Shortly before his death, Lepsius had given the author of these

lines the greatest mark of confidence that the student could receive

from the master who had directed with benevolent interest his

beginnings in the science of Egyptology. He had recommended to his

children to give me all of his notes and manuscripts, knowing that I

would only use them with the feelings of respect and recognition that

our past relationships had engendered in me. I therefore had Lepsius's

diary in my hand for a little over a year.

In 1886, at the

request of the Minister of Public Education of the Kingdom of Prussia,

and in agreement with the family of the deceased, it was decided that

the journal would be sent to the Berlin Library, where it has since

been deposited as property of the State, use being granted to scholars

who would like to consult it, but the right of publication being

reserved for the moment, in accordance with the last wishes of the

deceased. To this journal was later added Max Weidenbach's sketchbook

which I returned to the Library under the same conditions.

Fig.3:

Kurt Sethe (1869-1934) in 1918. Sethe, a student of Adolph Erman and a

Berlin Egyptologist, made numerous breakthroughs in the grammar of

ancient Egyptian and remains a chief authority on that language

Before

getting to work it was necessary to fix a point much discussed today

among Egyptologists, that of the transcription of hieroglyphs. Due to

the progress that has been made in deciphering, it has happened that

Lepsius during his career sometimes gave different readings of the same

sign. The question of transcription had preoccupied him on several

occasions, particularly when he wrote his memoir on the "Standard

Alphabet" (1855—1863), and later at the Congress of Orientalists in

London, in 1874. On the latter occasion , he proposed a system of

transcription that he wanted to see generally adopted, to which he was

very attached and which he applied throughout the time he was busy

editing the Zeitschrift. I

did not believe that we had the right to deviate from this system when

it came to publishing his journal. Knowing (p.viii) Lepsius' opinion

on this point, and the attachment he had for its transcription, it was

my duty to respect what was the result of his latest research, and not

to introduce any foreign element.

If there were corrections to

be made, it seemed to me that it was necessary to correct Lepsius

himself, and this is why we will find in these volumes the

transcription and the readings that he had adopted in the last years of

his life and particularly since 1874. Once this publication is

completed, it will be possible to make a definitive judgment on who

Lepsius was, on the extent of his activity, on the importance of his

work, and on everything of which he Egyptology is indebted to him. We

will recognize here, I am certain, what characterizes his other works,

the certainty in the method and the clarity in the exhibition.We will also discover what we were perhaps less

inclined to attribute to him, the intuition of the right solution in

many doubtful problems; and we will be surprised to see that more than

one discovery due to one of his successors, and which is perhaps even

considered as a very recent novelty, he had, if not made, at least

glimpsed. I am happy to think that this work will be an effective means

of making the great qualities of the one I had the privilege of having

as a master better known and more highly appreciated. And that it will

thus be the truest tribute and the most lasting that we can restore to

his memory.

Malagny near Geneve. June 1896.

EDOUARD NAVILLE.

Fig.4:

Edouard Naville (1844-1926) in 1917. Naville, a Swiss

archaeologist who was a student of Lepsius, conducted many pioneering excavations of sites in Egypt,

often published in Memoirs of the Egypt Exploration Account led by W.M. Flinders Petrie.

PRELIMINARY NOTE by Adolph Erman. (p.ix)

When

the expedition sent by His Majesty King Friedrich Wilhelm IV to Egypt

returned in 1846, the Most High Majesty made it possible for the

head of the company, Richard Lepsius, to present the results obtained

in the large work of illustrated tables of Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia [Denkmaler aus Agypten und Athiopian, afterwards abbbreviated here as DM],

which appeared between 1849 and 1859. As is clear from the announcement

of the work published in 1849, it was foreseen from the outset that

these plates would also be accompanied by an explanatory text and that

those drawings and inscriptions not included in the main work were to

be published in a supplementary volume in a smaller format. However,

both plans did not come to fruition. When, with Lepsius' death, the

possibility that he himself would publish this text and this

supplementary volume again disappeared, the plan was made to replace

these missing parts of the large work, to be completed based on the

materials left behind by the expedition. The following were available:

1. the copies and drawings of the expedition in the possession of the Royal Museums;

2.

the diaries and notebooks of Lepsius, which he

bequeathed to Mr. Edouard Naville in Geneva with his scientific estate;

3. the sketchbooks of Erbkam, who was involved in the expedition, in the possession of Miss Elisabeth Erbkam;

4. the sketchbook of Mr. Max Weidenbach, also owned by Mr. Naville in Geneva;

5.

Lepsius' copy of Rosellini's work, improved by him based on the

monuments on site. Owned by Mr. Heinrich Schaffer in Frankfurt on Main.

6. the list of antiquities, copies and drawings collected by the expedition. Owned by the Royal Museums.

All

of these materials were kindly provided by the relevant owners and sent

to Berlin. The publication of the work was carried out by Mr. Edouard

Naville (fig.4), who, according to a will of Privy Councilor Lepsius, is

entitled to publish his scientific legacy. The preparation was given to

Dr. Sethe (fig.3), who was assisted by government architect Borchardt for the

architectural sections; most of the sketches in the text are owed to

the latter.

The guidelines for the preparation of the volume of text

were already given by the principles laid down by Lepsius for his time:

no explaining of the representations and no transferring or commenting

on the inscriptions, but the text should tell every user of the tablets

“what he has in front of him, where It is taken from it and what else

initially turns out to be remarkable." Given the care with which

Lepsius recorded his observations, it was possible to compile the text

almost entirely from his diaries without changing the wording; of

course, different ones were included a monument regarding notes worked

together.

Wherever there was a need to deviate significantly from the

text of the diary, these changes were always marked, and all additions

that were added to make it easier to understand are in square brackets

[ ] .

Of the inscriptions (p.x) contained in the diaries, only

what was not yet published in the tablet volumes or published

differently was included; Here too, deviations that turned out to be

incorrect when comparing the copies were not taken into account. — A

revision of all the inscriptions on the volumes of plates was not

within the scope of the task. [2]

The arrangement of the text

could only be geographical; Following the system followed by Lepsius in

the volumes of tables, the sequence from north to south was observed

for the main area of the expedition. Monuments located outside Egypt

and Ethiopia, which are mentioned in the expedition diaries, will be

listed at the end. A chronological arrangement of the individual

monuments discussed could of course not be consistent with this system;

The small difficulty that may arise for a user of the table book will

be remedied by the concordance included at the end of the work.

At

the top of each page (fig.1), the manuscript sources used on it are

indicated in the following abbreviations, which are also used elsewhere

in the text:

"Fol." Lepsius' diary, folio volume (I—III);

"4"." same, fourth band (I—VI);

"12"." Lepsius' notebooks (I—X);

“Inv.

V." Inventory V of the Berlin Museum, the list of antiquities collected

by the expedition. (The lists of drawings and copies included in the

same volume are specially cited.)

"B." Berlin Museum, inventory number;

"Z." Drawing (the red order numbers of the drawings are quoted, not the black ones that refer to the "Inventory V")

"A." Paper print') (the lists in the "Inv. V" are quoted); [3]

"G." Plaster cast in the Berlin Museum (inventory numbers);

“M. W." Max Weidenbach's sketchbook;

“Erbk.Sk. B." Erbkam's sketchbook (two volumes 4to).

Since

it was necessary to observe a fixed procedure in the naming and dating

of kings, the system observed by Lepsius in the tablet volumes was used

throughout, which corresponds to the system he set up in the King's

Book. Noteworthy diary deviations from this system have always been

noted in the notes. For reasons that he himself explained in his

preface, at Mr. Naville's request, the type of paraphrase later

established by Lepsius was carried out instead of the slanting method

of the diaries. Of course, the architectural sketches also had to be

given a somewhat smoother appearance than they have in the fleeting

originals; Erbkam's sketchbooks offered significant help in this

regard. Where no scale is given next to a sketch, it is made in an

approximate ratio of 1: 200.

Adolf Erman

Fig.6:

Adolf Erman (1854-1937) was professor of Egyptology at the University

of Berlin, and for several decades led successful efforts to

reconstruct the ancient Egyptian language. His students included James

Breasted of the University of Chicago, as well as Kurt Sethe.

Footnotes:

1. All comments come from the editors. — References to other

publications by the same monumental painters have been added, as far as

it seemed desirable, without the aim being bibliographical completeness.

2.

In order to make it easier to check the inscriptions and illustrations,

the material available for this purpose will be listed in detail in the

concordance that concludes the work.

3. Since the paper

impressions are often compressed today, the readings based

on these should be used with caution unless the impression

is expressly described as good.

a.

Max Weidenbach (1823-1890), trained to copy hieroglyphs, at age 19

joined the three year expedition to Egypt along with his brother Ernst,

an artist. In addition to his sketchbook, utilized in the present work,

Max kept a diary which only in 2013 was rediscovered with his family

papers in Australia.

[Continue to next part]

[Return to Table of Contents]

|

v |