|

Selected Greek Vase Paintings, featuring Etruscan examples.

Vol. 2: Heroic Images.

(Published in 1843 as the second part of a 4-volume set, printed by G. Reimer in Berlin).

The introduction of wings in Greek vase paintings; wing shapes.

Plates LXXIX — LXXXIIl.

Between

the gods and the heroes, the imagination of educated Greece assigned

the demons their own place (1). All beings connecting man with the

highest power of the gods are included in this expression; they form a

host of ministering gods who, as outpourings of the divine power of the

Olympian gods, execute commands on earth (2) and sea, mountain and

forest. According to this concept, towns and houses are peopled with

tritons and nereids, pans and nymphs, and in the course of time also

with the eros figures, which some Roman as well as some modern usage

equates with the Italian genii.

The ancient Greek picture

gallery of our vases knew little of thatin relation to the serving

crowd of gods. At the sight of those old Attic works of art, richly

illustrated in the paintings of Etruscan origin, we cannot fail to

notice how precisely the expansion of Greek demonology is connected

with the progress of the plastic arts. A very important accessory to

the separation of those intermediate beings ruling between gods and

men, the wondrous connection of wings with the human form, found its

recognition only at a relatively late period (3).

Wings are

alien to the gods of Homer; In the first upsurge of Greek art at the

time of the tyrants, it was carried over from influences from the

Orient in many ways (p. 2) into Greek art, and incomparably more into

Etruscan works of art; but much was lacking in order to be able to

retain that strange form of culture in Greek art. Such a supernatural

addition made it all too difficult for human culture, which aspired to

nature and beauty, to combine it. Victory horses might have wings

earlier than it was considered permissible to form the messengers and

messengeresses of the gods with artificial wings; so was there less

reason to replace the gods, whom people loved to show in their own

majesty, by servant beings, whose valid expression art had not yet

found.

No matter how extensive the later sculpture was in the

erotic circle of winged boys, how exemplary were the Mysteries of Great

Greece, or how well known the broad wings of the goddess of victory may

be, the artistic evidence of our vase pictures confirms an otherwise

well-founded view, according to which the winged figures of both

Eros and Nike, did not appear until around the time of the Persian wars

(4).

This confirmation comes in abundance from the archaic

vase paintings. If in rare cases their circle of pictures lets us see a

winged boy, the meaning of this is not decidedly erotic; it is divided

between the demon of battle and demon of death (5). Instead of the

female winged figure, who, according to our most current idea, crowns

victors and performs sacrifices, Pallas Athene usually rewards the

heroes' struggle, or Artemis lends a hand to the Pythian donation (6);

indeed, where we meet a hurrying winged woman in the realm of that

older art, we are less entitled to mistake her for Nike,

notwithstanding her similar formation, than for the later vanished

goddess Eris (7) or for one of the goddesses of fate (8).

(p.5)

Finally, as sculpture progressed, ostentatiously evoked by

racetracks and theaters, these winged figures became more frequent,

their representation of the gods more permissible, their form and

meaning more understandable. Busy women, winged for infallible worship,

soon rise to become the most popular works of art; this also happened

with so many causes and accessories that their frequent appearance here

and there leaves us in doubt as to their significance.

To

unhesitatingly recognize the goddess of victory in a winged woman only

frees us according to the artistic usage of Roman times; In the age of

Greek art, on the other hand, with whose monuments we are concerned,

freedom was still unaffected, one and the same winged figure appears

through changing accessories and performance, sometimes as a physical

goddess of dawn, sometimes as the mediating messenger of the divine

decree, and sometimes as a goddess of dangerous victory , soon as

enforcers of sacred sacrificial custom, as a stewardess of godly

consecration or as a welcome goddess of youth and peace.

Thus

it happens that on works of art of the best time the same figure may

apply for Eos (9) and Iris (10), for Nike (11) and Telete (12), for

Hebe (13) as well as for Irene (14). Greek observers may not

infrequently have been embarrassed about the correct choice of these

names, and yet it is due to the explanation of art to limit the

interplay of those names as far as possible.

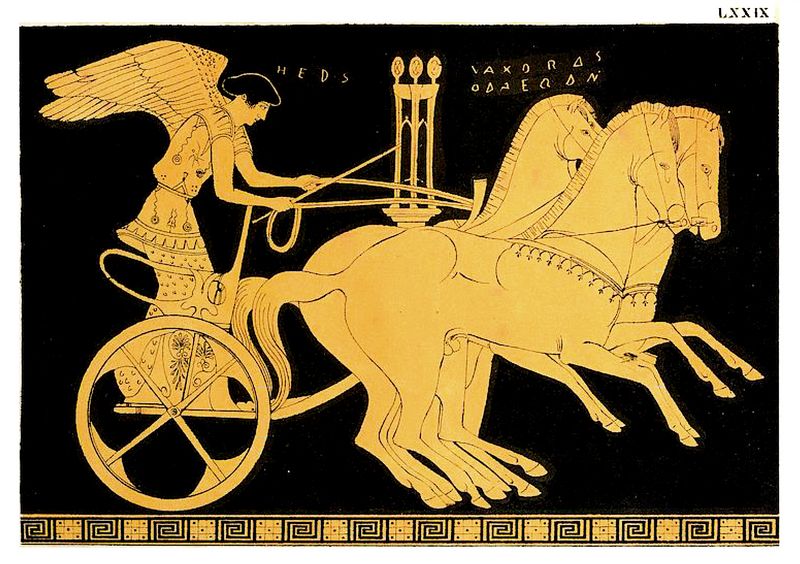

Plate LXXIX. Winged Eos; Stamnos with reddish figures, formerly with the art dealer Basseggio in Rome.

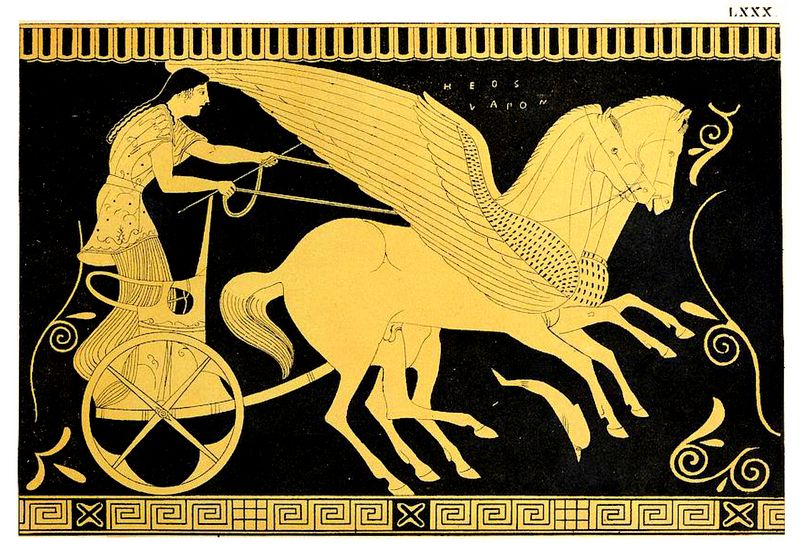

Plate 80: Eos, goddess of Dawn, with winged horses, from Etruscan vase painting.

Plate LXXX.

Eos

with winged horses; similar vessel (stamnos) in Durand's collection (15).

A

divine figure, which has become considerably more alien to the later

conception, occupies the place in earlier Greek art which Homer already

assigned to it among the governing (p. 6) heavenly powers. If in that

later conception the sun god outshines the goddess of Morgeuroth, then

in earlier times this goddess is to be emphasized so diligently in

speech and legend.

Homer is busy at the beginning of each day

mentioning the rosy traces of the Eos (16); Eos and Hemera, the goddess

of the morning light or of the day, have received a web of legends in

precocious sons and darlings (7) that Helios does not deserve in the

same splendor. This advantage, which the goddess of morning and day had

in the poetic conception of Greece over the sun god whom she proclaims,

is even more pronounced in the worship of the gods in Italy (18); so it

is less strange to see that aspiring goddess celebrated in older forms

of art with special emblems of her unstoppable course. We have two vase

pictures that are very similar to one another, in which their course

appear to be lifted by wings.

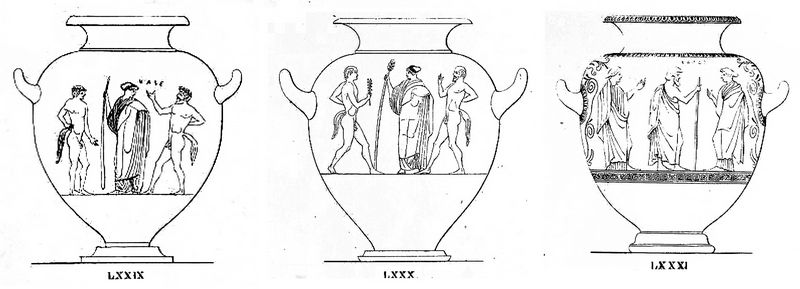

Fig.1: Vessel forms (stamnos) and reverse images of vessels in plates 79-81

However,

how this arrangement was carried out more according to artistic freedom

than according to an already established art practice is sufficiently

evident from the differently applied wings of the two pictures. On one

of them (plate 79) it is the goddess who, provided with broad shoulder

wings, hastens the course of her steeds; this way of representation,

which is attested from the best of times (19), is accompanied by the

other on the second of our vessels, according to which the wondrous

addition of wings was intended to make the impetuosity of the animals

more vivid (20). On the whole it is to be assumed that any inspiration

in pictures of the older art was rarely denied to the emerging goddess

of light (21); only when the concept and formation (p.7) of the goddess

of victory put every other winged figure in the shade was the goddess

of the morning light also frequently depicted wingless, with or without

wings on her horses (22).

We will now examine both images more

closely. On both we see the prudent leader of the light-bringing

steeds, reins and whip in her hands, standing on a light carriage and

being pulled forward. By ancient inscription, HEOZ ('Hoog), their

meaning is assured on both; The clothing of the goddess with a long

chiton and a short, belted, richly decorated outer garment, the

protruding hem of which indicates the heaviness of the fabric, is also

consistent on both.

Something else is different in the two

paintings, corresponding to the difference in wings. The winged goddess

of our first picture is drawn by four horses, whose course she hastens;

the unwinged goddess of the second suffices with two horses on wings,

whose impetuosity she seems to guard with some anxiety. How this pair

of wings rises above the waves of the sea is indicated by a dolphin,

whereas in the first of our pictures the elementary importance of the

goddess ascending in the firmament is subordinate to her relation to

the doings of mortals. This relationship is stimulated by a tripod

placed high up, and there is no doubt that this occasionally

misunderstood device is only to be interpreted as a prize for the

athletes (23): the one to whom it was intended in this picture saw the

goddess represented at the same time the morning light of the festive

day dedicated to him.

In the same way, the backs of both vessels

are decorated with pictures of personal reference; only that, after a

combination of athletic and nuptial references that we have often

noticed, the counter-image difference is namely on both reverse sides

of these vessels, which are so similar to one another, a bacchic

initiate, holding a more or less complete thyrsus in the hand,

connected with two silenae, as often happened in relation to the

Bacchic rites connected with marriage. A word of praise for the

beautiful bride (KALE = "beautiful woman"), cannot be overlooked in the

first picture (plate 79).

Two name inscriptions, which are above

the four steeds of the first picture, show the haste of the swift

animals in tail and mane (24), just as Hesiodus combines both

characteristics (25). Another inscription LAPON applies to one of the

horses of the second chariot: undoubtedly as a shining Lampon or

Lampos, as the same name with the related predicate of a Phaethon is

already assigned to the horses of Eos in Homer (26).

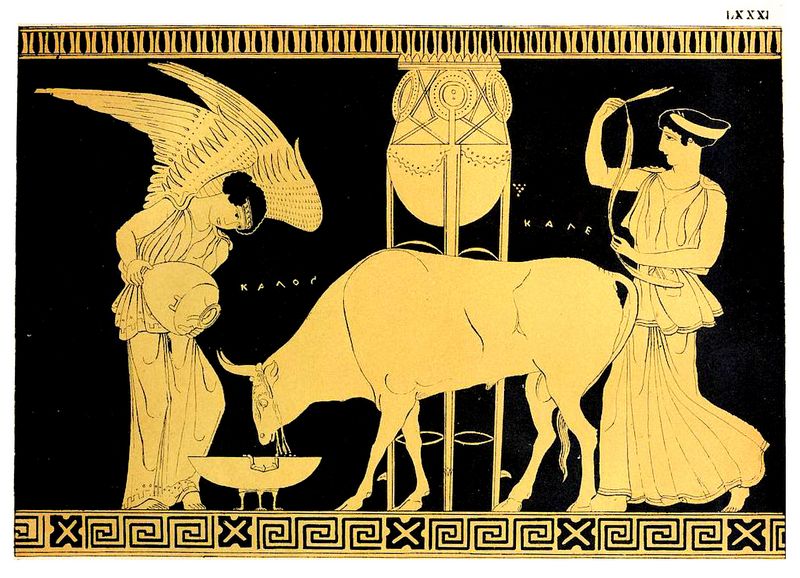

Plate 81: Winged Nike watering a bull prior to sacrificing it.

Plate LXXXI. Sacrificial Nike; Stamnos with reddish figures, belonging to the collection of the Prince of Canino (27).

From

the goddess just considered, whose wings were gradually given up as the

use of art progressed, we turn to the similar gods, who retained this

significant distinction for a longer period of time. With no other

goddess did this take place, with fewer exceptions (28) than with Nike,

the goddess of victory, whose term, however, has wider limits than the

most common usage indicates.

The ancient Greek scope of that

concept encompassed not only the accomplishment of the struggle to a

happy goal, but also the accomplishment of every other important work

in the service of the gods and for the help of mortals. Thus Nike is

not only (p.9) a goddess of battles, but also a guide of sacrifices; in

enemy's blood she fulfills the dictum of angry gods, but she also sheds

the sacrificial blood with her own hands, which is supposed to bind the

gods to man again.

Images of this latter subject are not rare.

The sacrifice of the bull consecrated to the gods, performed by a

winged goddess of victory, appears frequently on clay slabs, which,

despite the Roman period, bear the stamp of the noblest Greek art (29).

Sitting on this sacrificial bull willingly advancing towards its

destiny, Nike appears in a particularly remarkable gem image (30);

other times she leads him (31) or crowns him who has already sunk (32).

The presentation in this vessel (Plate 81) grants us a

moment in between. The sacrificial bull, which occupies the greater

part of the picture, is near its destination; he is festively wreathed

and a priestess approaches from behind with the intention of tying

decorative ribbons around him. Our Nike offers a helpful hand in this

care, which is part of the sacrifice. The sacrificial bull, which is to

face its death adorned and joyful (33), receives its last refreshment

from the same hand that will sacrifice it. A plentiful vessel of water

is poured into the three-footed basin that stands in front of him; the

frequent use of this attribute in similar winged forms (34) not only

helps to explain them, but also testifies to the importance of the

sacrificial custom presented to us here.

The special meaning of

the depicted victim is just as obvious. It is indicated to us by a

raised tripod (p.10), which we already know as the brazen

prize of victory in choral games (35), and find it celebrated elsewhere

by Nike the victor (36). Both the frequent relation of our vase

pictures to similar games, as well as the common Apollonian-Bacchic

relation of the same, was discussed by us earlier (37). In the same way

we proved the bull to be a well-known Bacchic sacrificial animal

alongside Apollo (38), and just as we see a Bacchic sacrifice in the

bull of our vase picture, the goddess of victory who sacrifices it is

also considered to be a Bacchic Nike (39) (p .11).

Her

concept coincides with that of a goddess of Bacchic consecration, a

Telete, as she is variously called (40) and in particular in relation

to bull sacrifice (41), but almost as aptly also Hosia (42) or, in

peaceful action, Irene ( 43), not to mention the equally valid names

Mystis (44), Eleusin (45), Euthymia (46), such as Iris (47), Dike (48)

and Hebe (49), who have sometimes been wrongly associated here (p.12).

Assigning

names of this kind to the different, wingless (50), or winged (51),

scantily clad (52) or veiled (53), stewards (p.13) of new Bacchic

festive usage, is an unjustly contested archaeological usage (54 ),

without the satisfaction of which the priestly executing Nike remains

unseparated from the goddess of victory in the throng of battle. The

only question that can be raised is whether those names are compatible

with the use of wings, which in and of themselves are neither of the

sacrificial Telete (55) nor of the blessed Irene (56), other

personified states and actions (57). Yet the frequently inconsistent

use of wings applied or omitted is proven enough to justify the added

wings of divine messengers here and there with gradually

increasing usage.

To complete the explanation of our

painting (fig.81), let us take a comparative look at the reverse side

of it. A bearded man with a propped staff appears there between two

women; the cheer that accompanies it, KALOS, is quite appropriate to

the double epithet assigned in masculine and feminine suffix, KALOS and

KALE, to the described position of our principal picture. Since there

is no male figure in this main image, the relationship between the two

epithets can only be personal, relating to the recipient of the vessel,

as it usually is with few exceptions (38), and accordingly our vessel

enters the series of the many similar vases, the two counter-images of

which refer to an interrelationship between two persons of opposite

sexes.

Assuming this, we cannot avoid looking again at the

main picture already discussed (p. 14) from the point of view of its

individual relationship. Just as the male KALOS, which is found there

without a corresponding image of a male person, receives its

explanation in the recipient's neighboring choragic tripod, the woman

attending the sacrifice, to which we find a KALE attached, may be a

person closely related to that recipient rather than a ordinary servant

of the victim. Form and clothing are unadorned; but even Nike wears no

decorative sign of her importance apart from wings and headband (59).

Regarding

the history of this beautiful vessel, it should also be noted that the

illustrious owner of it, with a feeling of Italian autochthony, related

the bull in our picture to Italy as the country designated by horned

cattle and the accompanying winged shape to a protective spirit of the

same (60). An archaeologist has shown how this ill-intentioned game of

explanation continues, the tripod surrounded by rays and wreaths at

best pointing to Vesuvius, whose fire and love can be pointed out (61);

These witty jests do not yield any scientific explanation.

Footnotes:

[Return to table of contents]

|

|