|

The Relation of the Archaic Pediment-Reliefs of the Acropolis to Vase Painting

(Article written in 1891, originally published in 1897 in Papers of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Volume VI, 1890-1897, pp. 302-317.)

From

one point of view it is a misfortune in the study of archaeology that,

with the progress of excavation, fresh discoveries are continually

being made. If only the evidence of the facts were all in, the case

might be summed up and a final judgment pronounced on points in

dispute. As it is, the ablest scholar must feel cautious about

expressing a decided opinion; for the whole fabric of his argument may

be overturned any day by the unearthing of a fragment of pottery or a

sculptured head. Years ago, it was easy to demonstrate the absurdity of

any theory of polychrome decoration. The few who dared to believe that

the Greek temple was not in every part as white as the original marble

subjected themselves to the pitying scorn of their fellows. Only the

discoveries of recent years have brought proof too positive to be

gainsaid. The process of unlearning and throwing over old and cherished

notions is always hard; perhaps it has been especially so in

archaeology.

The thorough investigation of the soil and rock of

the Acropolis lately finished by the Greek Government has brought to

light so much that is new and strange that definite explanations and

conclusions are still far away. The pediment-reliefs in poros which now

occupy the second and third rooms of the Acropolis Museum have already

been somewhat fully treated, especially in their architectural

bearings. Dr. Bruckner of the German Institute (p.303) has written a

full monograph on the subject,[1] and it has also been fully treated by

Lechat in the Revue Archeologique.[2] Shorter papers have appeared in the Mittheilungen

by Studniczka [3] and P. J. Meier. [4] Dr. Waldstein in a recent

peripatetic lecture suggested a new point of view in the connection

between these reliefs and Greek vase-paintings. It is this suggestion

that I have tried to follow out.

The groups in question are too

well known to need a detailed description here. The first,[5] in a

fairly good state of preservation, represents Hercules in his conflict

with the Hydra, and at the left Iolaus, his charioteer, as a spectator.

Corresponding to this, is the second group,[6] with Hercules

overpowering the Triton; but the whole of this is so damaged that it is

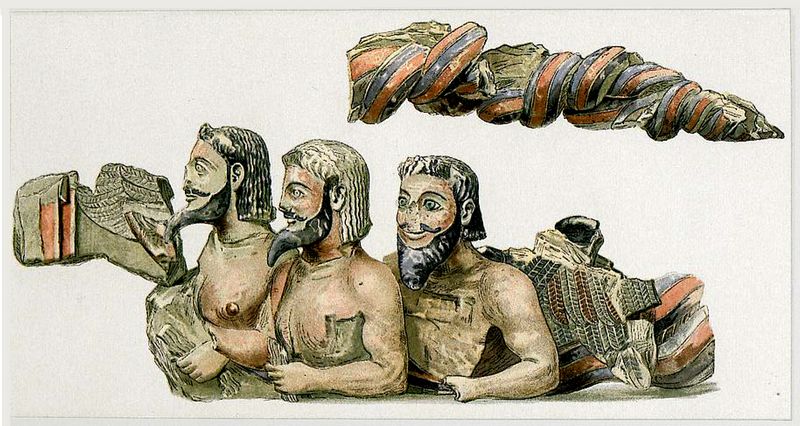

scarcely recognizable. Then there are two larger pediments in much

higher relief, the one [7] repeating the scene of Hercules and the

Triton, the other [8] representing the three-headed Typhon in conflict,

as supposed, with Zeus (plate 1). All four of these groups have been

reconstructed from a great number of fragments. Many more pieces which

are to be seen in these two rooms of the Museum surely belonged to the

original works, though their relations and position cannot be

determined. The circumstances of their discovery between the south

supporting-wall of the Parthenon and Cimon's inner Acropolis wall make

it certain that we are dealing with pre-Persian art. It is quite as

certain, in spite of the fragmentary condition of the remains, that

they were pedimental compositions and the earliest of the kind yet

known.

Plate 1: The Typhon Pediment of the Acropolis (from Plate 21, Brownson 1897)

The first question which presents itself in the present

consideration is: Why should these pedimental groups follow

vase-paintings? We might say that in vases we have practically the

first products of Greek art; and further we might show resemblances,

more or less material, between these archaic reliefs and vase pictures.

But the proof of any connection between the two would still be wanting.

Here the discoveries made by the Germans at (p.304) Olympia and

confirmed by later researches in Sicily and Magna Graecia, are of the

utmost importance.[9] In the Byzantine west wall at Olympia were found

great numbers of painted terracotta plates [10] which examination

proved to have covered the cornices of the Geloan Treasury. They were

fastened to the stone by iron nails, the distance between the

nail-holes in terracottas and cornice blocks corresponding exactly. The

fact that the stone, where covered, was only roughly worked made the

connection still more sure. These plates were used on the cornice of

the long side, and bounded the pediment space above and below. The

corresponding cyma was of the the same material and similarly decorated.

It

seems surprising that such a terracotta sheathing should be applied on

a structure of stone. For a wooden building, on the other hand, it

would be altogether natural. It was possible to protect wooden columns,

architraves and triglyphs from the weather by means of a wide cornice.

But the cornice itself could not but be exposed, and so this means of

protection was devised. Of course no visible proof of all this is at

hand in the shape of wooden temples yet remaining. But Dr. Dorpfeld's

demonstration [11] removes all possible doubt. Pausanias [12] tells us

that in the Hereum at Olympia there was still preserved in his day an

old wooden column. No from the same temple no trace of architrave,

triglyph or cornice has been found; a fact that is true of no other

building in Olympia and seems to make it certain that here wood never

was replaced by stone. When temples came to be built of stone, it seems

that this plan of terracotta covering was retained for a time, partly

from habit, partly because of its fine decorative effect. But it was

soon found that marble was capable of withstanding the wear of weather

and that the ornament could be applied to it directly by painting.

(p.305)

In order to carry the investigation a step further Messrs. Dorpfeld,

Graber, Borrmann and Siebold undertook a journey to Gela and the

neighboring cities of Sicily and Magna Grsecia.[13] The results of this

journey were most satisfactory. Not only in Gela, but in Syracuse,

Selinus, Acrse, Croton, Metapontum and Paestum, precisely similar

terracottas were found to have been employed in the same way.

Furthermore just such cyma pieces have been discovered belonging to

other structures in Olympia and amid the pre-Persian ruins on the

Acropolis of Athens. It is not yet proven that this method of

decoration was universal or even widespread in Greece; but of course

the fragile nature of terracotta and the fact that it was employed only

in the oldest structures, would make discoveries rare.

Another

important argument is furnished by the certain use of terracotta plates

as acroteria. Pausanias [14] mentions such acroteria on the Stoa

Basileios on the agora of Athens. Pliny [15] says that such works

existed down to his day, and speaks of their great antiquity.

Fortunately a notable example has been preserved in the acroterium of

the gable of the Heraeum at Olympia,[16] a great disk of clay over

seven feet in diameter. It forms a part, says Dr. Dorpfeld, of the

oldest artistic roof construction that has remained to us from Greek

antiquity. That is, the original material of the acroteria was the same

used in the whole covering of the roof, namely terracotta. The

gargoyles also, which later were always of stone, were originally of

terracotta. Further we find reliefs in terracotta pierced with

nail-holes and evidently intended for the covering of various wooden

objects; sometimes, it is safe to say, for wooden sarcophagi. Here

appears clearly the connection that these works may have had with the

later reliefs in marble.

To make now a definite application, it

is evident that the connection between vase-paintings and painted

terracottas must from the nature of the case be a very close one. But

when these terracottas are found to reproduce throughout the exact

designs and figures of vase-paintings, the line between the two fades

away. All the most familiar ornaments of vase technic recur again and

(p.306) again, maeanders, palmettes, lotuses, the scale and

lattice-work patterns, the bar-and-tooth ornament, besides spirals of

all descriptions. In execution, also, the parallel is quite as close.

In the great acroterium of the Herseum, for example, the surface was

first covered with a dark varnish-like coating on which the drawing was

incised down to the original clay. Then the outlines were filled in

black, red and white. Here the bearing becomes clear ot an incidental

remark of Pausanias in his description of Olympia.

He says (v. 10.):

xxx xxx xxxx. That is, originally acroteria were only vases set

up at the apex and on the end of the gable. Naturally enough the later

terracottas

would keep close to the old tradition.

It is

interesting also to find relief-work in terracotta as well as painting

on a plane surface. An example where color and relief thus unite, which

comes from a temple in Caere,[17] might very well have been copied from

a vase design. It represents a female face in relief, as occurs so

often in Greek pottery, surrounded by an ornament of lotus, masander

and palmette. Such a raised surface is far from unusual; and we seem to

find here an intermediate stage between painting and sculpture. The

step is indeed a slight one. A terracotta figurine [18] from Tarentum

helps to make the connection complete. It is moulded fully in the

round, but by way of adornment, in close agreement with the tradition

of vase-paintingi the head is wreathed with rosettes and crowned by a

single palmette. So these smaller covering plates just spoken of, which

were devoted to minor uses, recall continually not only the

identical manner of representation but the identical scenes of vase

paintings,— such favorite subjects, to cite only one example, as the

meeting of Agamemnon's children at his tomb.

From this point

of view, it does not seem impossible that pedimental groups might have

fallen under the influence of vase technic. The whole architectural

adornment of the oldest temple was of pottery. It covered the cornice

of the sides, completely bounded the pedimental space, above and below,

and finally (p.307) crowned the whole structure in the acroteria. It

would surely be strange if the pedimental group, framed in this way by

vase designs, were in no way influenced by them. The painted decoration

of these terracottas is that of the bounding friezes in vase ictures.

The vase-painter employs them to frame and set off the central scene.

Might not the same end have been served by the terracottas on the

temple, with reference to the scene within the typanum ? We must

remember, also, that at this early time the sculptor's art was in its

infancy, while painting and the ceramic art had reached a considerable

development. Even if all analogy did not lead the other way, an artist

would shrink from trying to fill up a pediment with statues in the

round. The most natural method was also the easiest for him.

On

the question of the original character of the pedimental group, the

Heraeum at Olympia, probably the oldest Greek columnar structure known,

furnishes important light. Pausanias says nothing whatever of any

pedimental figures. Of course his silence does not prove that there

were none; but with all the finds of acroteria,

terracottas and the

like, no trace of any such sculptures was discovered. The inference

seems certain that the pedimental decoraion, if present at all, was

either of wood or of terracotta, or was merely painted on a smooth

surface. The weight of authority inclines to the last view. It is held

that, if artists had become

accustomed to carving pedimental groups

in wood, the first examples that we have in stone would not show so

great inability to deal with the conditions of pedimental composition.

If ever the tympanum was simply painted or filled with a group in

terracotta, it is easy to see why the fashion died and why consequently

we can bring forward no direct proof to-day. It was simply that only

figures in the round can satisfy the requirements of a pedimental

composition. The strong shadows thrown by the cornice, the distance

from the spectator, and the height, must combine to confuse the lines

of a scene painted on a plane surface, or even of a low relief. So soon

as this was discovered and so soon as the art of sculpture found itself

able to supply the want, a new period in pedimental decoration began.

Literary

evidence to support this theory of the origin of pediment sculpture is

not lacking. Pliny says in his Natural History (p.308) (xxxv. 156. j:

Lauded (Varro) et Pasitelen qui plasticen matron caclaturae et

statuariae sculptwaeque dixit et cum esset in omnibus his summits nihil

unquam fecit antequam finxit. Also (xxxiv. 35.): Similitudines

exprimendi quae prima fuerit origo, in ea quam plasticen Graeci vocant

did comerdentius erit, etenim prior quam statuaria fuit. In both these

cases the meaning of " plasticen " is clearly working, that is,

moulding, in clay. Pliny, again (xxxv. 152.), tells us of the

Corinthian Butades: Butadis inventum est rubricam addere aut ex rubra

ereta fingere, primusque personas tegularum extremis imbricibus

inposuit, quae inter initia prostypa vocavit, posiea idem ectypa fecit,

hinc et fastigia templorum orta. The phrase hinc et fastigia temphrum

orta, has been bracketed by some editors because they could not believe

the fact which it stated. Fastigia may from the whole connection and

the Latin mean " pediments." This is quite in accord with the famous

passage in Pindar,[19] attributing to the Corinthians the invention of

pedimental composition. Here then we have stated approximately the

conclusion which seems at least probable on other grounds, namely, that

the tympanum of the pediment was originally filled with a group in

terracotta, beyond doubt painted and in low relief.

But if we

assume that the pedimental group could have originated in this way, we

must be prepared to explain the course of its development up to the

pediments of Aegina and the Parthenon, in which we find an entirely

different principle, namely, the filling of these tympana with figures

in the round. It is maintained by some scholars, notably by Koepp [20]

that no connection can be established between high relief and low

relief, much less between statues entirely in the round and low relief.

High relief follows all the principles of sculpture, while low relief

may almost be considered as a branch of the painter's art. But this

view seems opposed to the evidence of the facts. For there still exists

a continuous series of pedimental groups, first in low relief then in

high relief, and finally standing altogether free from the background,

and becoming sculpture in the round.

Examples in low relief are

the Hydra pediment from the Acropolis and the pediment of the Megarian

Treasury at Olympia, which, on artistic (p.309) grounds, can be set

down as the two earliest now in existence. Then follow, in order of

time and development, the Triton and Typhon pediments, in high relief,

from the Acropolis; and after these the idea of relief is lost, and the

pediment becomes merely a space destined to be adorned with statuary.

Can we reasonably believe that the Hydra and Triton pediments, standing

side by side on the Acropolis, so close to each other in time and in

technic, owe their origin to entirely different motives, merely for the

reason that the figures of one stand further out from the background

than those of the other'( Is it not easier to suppose that the higher

reliefs, as they follow the older low reliefs in time, are developed

from them, than to assume that just at the dividing-line a new

principle came into operation ?

In

the second step of the stereobate, under the great pier just mentioned,

and in a stone now lying near it, are the remains of an ancient drain

discovered by Botticher in 1862, the purpose of which has always been

more or less enigmatical. The direction of the drain is from the corner

by the porch of the Kopa. This corner was, as we have seen, probably

occupied by a building, the water from the roof of which must have run

off into the enclosed court-yard west of the Erechtheion. The drain was

probably intended merely to carry off this rain-water.

It

is a commonplace to say that sculpture in relief is only one branch of

painting. Conze [21] publishes a sepulchral monument which seems to him

to mark the first stage of growth. The surface of the figure and that

of the surrounding ground remain the same; they are separated only by a

shallow incised line. Conze says of it ; " The tracing of the outline

is no more than, and is in fact exactly the same as, the tracing

employed by the Greek vase-painter when he outlined his figure with a

brush full of black paint before he filled in with black the ground

about it." The next step naturally is to cut away the surface outside

and beyond the figures; the representation is still a picture except in

the clearer marking of the bounding-line. The entire further growth and

development of the Greek relief is in the direction of rounding these

lines and of detaching the relief more and more from the back surface.

This primitive picturesque method of treatment is found as well in high

relief as in low. How then can the process of development be different

for the two ? I quote from Friederich Wolters [22] on the metopes of

the temple of Apollo at Selinus, which are distinctly in high relief: "

The relief of these works stands very near to the origin of relief style.

The

surface of the figures is kept flat throughout, although the effort to

represent them in their full roundness is not to be (p.310)mistaken.

Only later were relief-figures rounded on the front and sides after the

manner of free figures. Originally, whether in high or in low relief,

they were flat forms, modelled for the plane surface whose ornament

they were to be." As the sculptured works were brought out further and

further from the background, this background tended to disappear. It

was no longer a distinctly marked surface on which the figures were

projected, but now higher and now lower, serving only to hold the

figures together. When this point was reached, the entire separation of

the figures from one another and from the background, became easy. That

is, the change in conception is an easy step by which the relief was lost

and free-standing figures substituted. This process of change was

especially rapid in pedimental groups, for the reason stated above. The

pediment field from its architectonic conditions was never suited to

decoration in relief. But we find from the works before us that such a

system was at least attempted, that painting and an increased

projection of relief were employed as aids. "We are bound to seek a

logical explanation of the facts and of their bearing on the later

history of art, and it is safer to assume a process of regular

development than a series of anomalous changes.

Koepp (cf.

supra), for example, assumes that these two pediments in low relief are

simply exceptions to the general rule, accounting for them by the fact

that it was difficult to work out high reliefs from the poros stone of

which they were made. He seems to forget that the higher reliefs from

the Acropolis are of the same poros.

This material in fact appears

to have been chosen by the artist because it was almost as easy to

incise and carve as the wood and clay to which he had been accustomed.

The monuments of later Greek art give no hint of a distinction to be

drawn between high and low relief. We find on the same stele figures

barely attached to the ground, and others in mere outline. If then

there are reasons for finding the origin of pedimental decoration in a

plane or low relief composition of terracotta, made more effective both

by a framing of like material and technic, and by the acroteria at

either extremity and above, then the process of development which leads

at length to the pediments at Aegina and the Parthenon becomes at once

easy and natural. We note first the change from terracotta to a low

painted relief in stone, then this relief becomes, (p.311) from the

necessities of the ease, higher and higher until finally it gives place

to free figures.

If ceramic art really did exert such an

influence on temple sculpture, we should he ahle to trace analogies in

other lines. The most interesting is found in the design and execution

of sepulchral monuments. Milehhoefer [23] is of the opinion that the

tomb

was not originally marked by an upright slab with sculptured figures.

He finds what he thinks the oldest representation or sepulchral

ornament in a black-figured vase of the so-called " prothesis " class.

[24] Here are two women weeping about a sepulchral mound on which rests

an amphora of like form to the one that bears the scene. He maintains

then that such a prothesis vase was the first sepulchral monument, that

this was later replaced by a vase of the same description in marble, of

course on account ot the fragile nature of pottery. For this reason,

too, we find no certain proof of the fact in the old tombs, though Dr.

Wolters [25] thinks that the discovery of fragments of vases on

undisturbed tombs makes the case a very strong one. The use of such

vases or urns of marble for this purpose became very prevalent. They

are nearly always without ornament, save for a single small group, in

relief or sometimes in color, representing the dead and the bereaved

ones. A very evident connecting-link between these urns and the later

sepulchral stele appears in monuments which show just such urns

projected in relief upon a plane surface. The relief is sometimes

bounded by the outlines of the urn itself, [26] sometimes a surrounding

background is indicated. In many cases this back, ground assumes the

form of the ordinary sepulchral stele. The Central Museum at Athens is

especially rich in examples of this kind. On two steles which I have

noticed there, three urns are represented side by side. A still more

interesting specimen is a stone so divided that its lower part is

occupied by an urn in relief, above which is sculptured the usual scene

of parting.

(p.312) This scene has its normal place as a

relief or a drawing- in color on the surface of the urn itself; here,

where the step in advance of choosing the plane stele to hear the

relief seems already taken, the strength of tradition still asserts

itself, and a similar group is repeated on the rounded face of the urn

helow. The transition to the more common form of sepulchral monument

has now become easy; but the characteristics which point to its genesis

in the funeral vase are still prominent.

This process of

development, so far as can be judged from existing types, reaches down

to the beginning of the fourth century BC. Steles of a different class

are found, dating from a period long before this. Instead of a group,

they bear only the dead man in a way to suggest bis position or

vocation during life. All show distinctly a clinging to the technic of

ceramic art. Sculptured steles and others merely painted exist side by

side. The best known of the latter class is the Lyseas stele, in the

Central Museum at Athens. Many more of the same sort have been

discovered, differing from their vase predecessors in material and

form, but keeping to the old principles. The outlines, for example, are

first incised, and then the picture is finished with color. The

Aristion stele may be taken as an example of the second order. Relief

plays here the leading part; but it must still be assisted by painting,

while the resemblance to vase-figures in position, arrangement of

clothing, proportion and profile, remains as close as in the simply

painted stele. An ever present feature, also, is the palmette

acroterium, treated in conventional ceramic style. Loeschcke [27]

thinks that the origin of red-figured pottery is to be found in the

dark ground and light coloring of these steles. Whether the opinion be

correct or not, it points to a very close connection between the two

forms of art.

The influence of ceramic decoration spread still

further. Large numbers of steles and bases for votive offerings have

been discovered on the Acropolis, which alike repeat over and over

again conventional vase-patterns, and show the use of incised lines and

other peculiarities of the technic of pottery.[28]

As to

specific resemblances between the pediments of the Acropolis and vase

pictures, the subjects of all the groups are such (p.313) as appear

very frequently on vases of all periods. About seventy Attic vases are

known which deal with the contest of Hercules and Triton. One of these

is a hydria at present in the Berlin Museum, ]STo. 1906. [29] Hercules is

represented astride the Triton, and he clasps him with both arms as in

the Acropolis group. The Triton's scaly length, his fins and tail, are

drawn in quite the same way. It is very noticeable that on the vase the

contortions of the Triton's body seem much more violent; here the

sculptor could not well follow the vase-painter so closely. It was far

easier for him to work out the figure in milder curves; but he followed

the vase-type as closely as possible. On the other hand, if the potter

had copied the pedimental group the copy could perfectly well have been

an exact one. The group is very similar also to a scene in the Assos

frieze, with regard to which I quote from Friederichs-Wolters; [30] "It

corresponds to the oldest Greek vase paintings, in which we find beast

fights borrowed from Oriental art, united with Greek myths and

represented after the Greek manner." This frieze is ascribed to the

sixth century BC, and is not much later than our pediments.

For

the Hydra pediment, there exists a still closer parallel, in an archaic

Corinthian amphora, published by Gerhard.[31] Athena appears here as a

spectator, though she has no part in the pedimental group; but in every

other point, in the drawing of the Hydra, of Hercules and Iolaus, the

identity is almost complete. Athena seems to have been omitted, because

the artist found it difficult to introduce another figure in the narrow

space. Evidently the vase must have represented a type known to the

sculptor and copied by him.

For

the Typhon pediment, no such close analogies are possible, at least in

the form and arrangement of figures. It would seem that this is so

simply because no vase picture of this subject that (p.314) we know so

far answers the conditions of a pedimental group that it could be used

as a pattern. In matters of detail, a hydria in Munich, No. 125

[32] offers the best illustration. For example, the vase painting

and the relief show quite the same treatment of hair, beard and wings

in the figure of Typhon.

Speaking

more generally, we find continually in the pediments reminiscences of

ceramic drawing and treatment. The acroteria, painted in black and red

on the natural surface of poros stone, take the shape of palmettes and

lotuses. The cornices above and below are of clay or poros, painted

in just such designs as appear on the Olympian terracottas; and these

designs are frequently repeated in the sculptures themselves. The

feathers of Typhon's wings are conventionally represented by a

scale-pattern; the arc of the scales has been drawn with compass; we

observe still the hole left in the centre by the leg of the compass.

The larger pinions at the ends of the wings have been outlined

regularly by incised lines, and then filled up with color.

All this is

as like the treatment of vase-figures, as it is unlike anything else in

plastic art. In the former the scale-pattern is used conventionally to

denote almost anything.Fragments of vases found on the Acropolis

itself picture wings in just this way; or it may be Athena's segis, the

fleece of a sheep or the earth's surface that is so represented. On the

body of the Triton and the Echidna of the pediments no attempt is made

to indicate movement and contortion by the position of the scales; it

is everywhere the lifeless conventionality of archaic vase-drawing. In

sculptured representations the scale device is dropped, and with it the

rigid regularity in the ordering of the pinions. Further, in drawing

the scales of the Triton, the artist has dropped usual patterns and

copied exactly a so-called bar-ornament which decorates the cornice

just over the pediment. Here again he chooses one of the most common

motives on vases. For the body of the Echidna, on the other hand, it is

the so-called lattice-work pattern which represents the scale

covering,—a pattern employed in vases for the most varied purposes, and

found on the earliest Cypriote pottery. Even the roll of the

snake-bodies of Typhon seems to follow a conventional spiral which we

find on old Rhodian ware.

[p.315] The outlining and coloring of

the figures is most interesting. The poros stone of the reliefs is so

soft that it could easily be worked with a knife; so incised lines are

constantly used, and regular geometrical designs traced. Quite an

assortment of colors is employed: black, whits, red, dark brown,

apparent green, and in the Typhon group, blue. It is very noticeable

that these reliefs, unlike the others which in general furnish the

closest analogies, the metopes of the temple at Selinus and the

pediment of the Megarian Treasury at Olympia, have the ground

unpainted. This is distinctly after the manner of the oldest Greek

pottery and of archaic wall paintings. Herein they resemble also

another archaic pedimental relief, found near the old temple of

Dionysus at Athens, and representing just such a procession of satyrs

and mrenads as appears so often on vases.

To give a local

habitation to the class of pottery which most nearly influenced the

artist of these reliefs, is not easy. Perhaps it is a reasonable

conjecture to make it Camirus of Rhodes. Camirus ware shows just such

an admixture of oriental and geometrical designs as characterizes our

pediments. Strange monsters of all kinds are represented there; while

in the reliefs before us a goodly number of such monsters are

translated to Greek soil.

Carleton L. Brownson.

American School of Classical Studies,

Athens, Nov. 10, 1891.

Footnotes:

1 Mitth. deutsch. arch. Inst. Athen, XIV, p. 67; xv, p. 84.

2. Rev. Arch., XVH, p. 304 ; xvin, pp. 12, 137.

3. Mitth. Athen, xi, p. Gl.

4. X, pp. 237, 322. Cf. Studniczka, Jahrbuch deutsch. arch. Inst., I, p. 87; Purgold, xxxx xxxxx 1884, p. 147, 1885, p. 234.

5. Mitth. Athen, X, cut opposite p. 237; 'KQ-ruitpis, 1884, jrivaf 7.

6. Mitth. Athen, XI, Tqf. 11.

7. Idem, XV, Taf. 11.

8. Idem, XIV, Taf. 11, in.

9. I follow closely Dr. Dorpfeld's account and explanation of these discoveries in

Ausgrabungen zu Olympia, V, 30 seq. See also Programm zum Winckelmannsfeste,

Berlin, 1881 ; Ueber die Verwendung Terracotien, by Messrs. Dorpfeld, Graeber,

Borrmann, and Siebold.

10. Reproduced in Ausgrabungen zu Olympia, V, Taf. xxxiv; BaumbISTKR, Donkmaler des klassischen Altertums, Taf. xlv ; Raykt et Collignon, Histoire de la Ceramique Grecque, pi. xv.

11. Historische und philologische Aufsdlze, Ernst Curtius gewidmet, Berlin, 1884,

p. 137 seq. 13 v, 20. 6.

12.

13. Cf. supra, Programm zum Winckelmannsfesie.

14. 1, 3. 1.

15. Hist. Nat., xxxv, 158.

16. Ausgrabungcn zu Olympia, v, 35 and Taj. XXXIV.

17. Arch. Zeitung, xxix, 1872, Taf. 41; Rayet et Collignon, Hist. Ceram. Grecque, fig. 143.

18. Arch. Zeitung, 1882, Taf. 13.

19. Olymp., xni, 21.

20. Jahrbuch deutschen archaol. Inutituis, II, 118.

21. Das Relief bei den Griechen, SUzungs-Berichte der Berliner Akademie, 1882, 507.

22. Gipsabgiisxc antiker Pi/denrerkc, Nos. 149—151.

23. Mitth. Athen, V, 164.

24. Monumenti dell' List., VIII, tav. v. 1. g. h. : found near Ciipe Colias; at

present in the Polytechnic Museum at Athens.

25. Attische Giytbvasen, a paper read before the German Institute in Atbrti.-, Dec. 9, 1890.

26.

Examples are Nos. 2099 and 2100 in the archaic room of the Louvre. I

remember having seen nothing similar in any other European museum

27. Mitth. Athen, IV, 36.

28. Borrmann, Jahrbuch des Institute, nr, 274.

29. Published by Gerhard, Auserlesene griechische Vasenbilder, No. Ill ; Kaybt

et Collignon, Hist. Ceram. Grecque, fig. 57, p. 125. In the National Museum at

Naples is a black-figured amphora, No. 3419, which repeats the same scene. The

drawing and position of the two contestants is just as on the Berlin vase, the Triton

seeking with one hand to break Hercules' hold about his neck, while with the other

he holds a fish as attribute. Athena stands close by, watching the struggle.

30. Gipsabgiisse antikcr Bildwerke, Nos. 8-12.

31. Auserlesene Vasenbilder, Nos. 95, 96.

32. Auserlesene Vasenbilder, No. 237.

[Return to table of contents]

|

|