Athena Review Vol. 5, no. 1

Records of Life: Fossils as Original Sources

42. Hominins: Australopithecus africanus to Homo habilis

South African sites: Mid Pliocene to Early Pleistocene

Australopithecus africanus lived

from 3.67 to 2 million years ago in the Middle Pliocene to Early

Pleistocene of South Africa. The species has been recovered from

limestone caves at Taung and Sterkfontein, Makapansgat, and Gladysvale.

The larger, contemporary species Paranthropus robustus has been recovered from limestone formations at nearby Swartkrans and Drimolen (Herries et al. 2020).

Australopithecus africanus lived

from 3.67 to 2 million years ago in the Middle Pliocene to Early

Pleistocene of South Africa. The species has been recovered from

limestone caves at Taung and Sterkfontein, Makapansgat, and Gladysvale.

The larger, contemporary species Paranthropus robustus has been recovered from limestone formations at nearby Swartkrans and Drimolen (Herries et al. 2020). The first Australopithecus to be discovered, and the first hominin fossil known from South Africa, was the 2.8 million year old juvenile skull, called the Taung child, found by anatomist Raymond Dart in 1924. Dart (1925) interpreted it as a transitional fossil between apes and humans. A. africanus provided the first evidence that humans evolved in Africa, as Charles Darwin had predicted in The Descent of Man (1871).

Fig.1: Map of hominin fossil sites in South Africa.

Many hominin fossils assigned to A. africanus have been recovered from Sterkfontein Member 4, including "Mrs. Ples" and two partial skeletons found by Robert Broom, dating from 2.8–2.15 mya. In addition to Taung, Sterkfontein, and Makapansgat, A. africanus was in 1992 discovered in Gladysvale Cave, located 28 km northwest of Johannesburg (Berger et al. 1993).

Australopithecus africanus

The Taung child

In 1924 Raymond Dart, a professor of anatomy, and geologist Robert B. Young, were searching for monkey fossils in a limestone quarry at Taung, South Africa, when they found a skull cap that fit precisely over a brain-cast protruding from the rock surface. Once the skull (fig.2) was removed, it was recognized by Dart to be a juvenile of an early hominin. Most notably, it had a small brain size, yet, based on the location of the foramen magnum (where the spinal cord joins the skull), was apparently bipedal. Dart named the specimen Australopithecus africanus (“southern ape of Africa”). The limestone formation producing the fossil is now dated at 2.8 mya, near the end of the Pliocene.

Fig.2: Skull of A. africanus fom Taung, South Africa (Yale Peaody Museum cast; photo: Athena Review).

In a 1925 paper published in Nature, Dart proposed that A. africanus represented a missing link between apes and humans, since it combined humanlike teeth and upright posture with a small cranial capacity. In this Dart was to be proven correct.

A. africanus brain volume was about 420–510 cc. Like other early hominins, the molars or cheek teeth were enlarged and had thick enamel, contrasting with the thin-enamelled molars of chimpanzees and gorillas, both primarily fruit eaters. A. africanus had a highly variable diet which probably included nuts, and lived in a gallery forest surrounded by more open grasslands or bushlands. South African australopithecine remains probably accumulated in caves due to predation by large carnivores including big cats (Brain 1983). Based on perforations around the eyes of its skull, the Taung child may have been killed by a bird of prey, such as an eagle (Berger and McGraw 2007).

Sexual dimorophism was present in A. africanus, with males larger, averaging 140 cm (4 ft 7 in) in height and 40 kg (88 lb) in weight, compared to females whose height averaged 125 cm (4 ft 1 in) and weighed 30 kg (66 lb). While bipedal, A. africanus was less efficient at walking than humans. Features of the upper body similar to those of arboreal apes included long arms.

Raymond Dart

Raymond Arthur Dart (1893–1988), an Australian-born anatomist and paleoanthropologist who worked in South Africa, was the discoverer of the Taung child, and the first scientist to recognize an australopithecine.

A

fter attending

medical school in Sydney, Dart served in World War I as a doctor. In

1922, he became a professor of anatomy at the University of the

Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. In 1924 he found a skullcap in a quarry

at Taung that fit precisely over a brain-cast protruding from the

surface of one of the rocks. Once the skull was removed, it was

recognized by Dart to be a juvenile of an early hominin, which Dart

named Australopithecus africanus (“southern ape of Africa”).

fter attending

medical school in Sydney, Dart served in World War I as a doctor. In

1922, he became a professor of anatomy at the University of the

Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. In 1924 he found a skullcap in a quarry

at Taung that fit precisely over a brain-cast protruding from the

surface of one of the rocks. Once the skull was removed, it was

recognized by Dart to be a juvenile of an early hominin, which Dart

named Australopithecus africanus (“southern ape of Africa”).In his 1925 paper published in Nature, Dart proposed that A. africanus represented a missing link between apes and humans, since it combined humanlike teeth and upright posture with a small cranial capacity. Dart's find was dismissed by the originators of the spurious Piltdown fossil, which showed an ape's features with a human size brain (the opposite of Dart's accurate view). The Taung find also became overshadowed by the 1930 discovery of a largely intact Homo erectus skull at Zhoukoudian, China.

Fig.3: Raymond Dart holding the Taung skull (photo: Witwatersrand University, 1925).

In the 1930s, however, Dart became friends with Robert Broom. In the 1940’s, encouraged by Broom, Dart returned to fossil hunting and found more australopithecine remains in a cave at Makapansgat (Dart 1949).Mrs. Ples

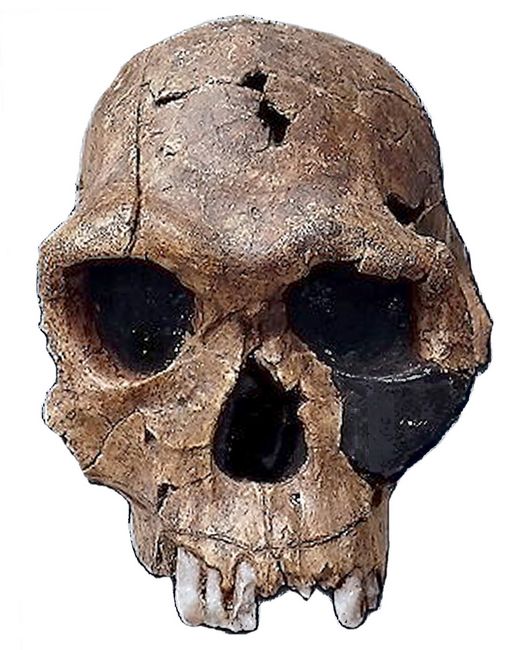

In 1947 Robert Broom and John T. Robinson found a nearly complete skull (fig.4) of an adult hominin in a cave near Sterkfontein, South Africa. The site is about 40 km NW of Johannesburg in a limestone region of the Transvaal. The skull was nicknamed "Mrs. Ples" from the name Plesianthropus transvaalensis ("nea

r-man

from the Transvaal"), that Broom initially gave the skull. It is now

considered part of the species Australopithecus africanus.The skull (cat. # STS

5) is at the Transvaal Museum, Northern Flagship Institute,

Pretoria, South Africa.

r-man

from the Transvaal"), that Broom initially gave the skull. It is now

considered part of the species Australopithecus africanus.The skull (cat. # STS

5) is at the Transvaal Museum, Northern Flagship Institute,

Pretoria, South Africa.Fig.4: Skull of adult A. africanus ("Mrs. Ples") from Sterkfontein cave in South Africa (photo: Transvaal Mus.)

Lacking upper teeth and mandible, Mrs. Ples is still the most complete skull of an Australopithecus africanus ever found in South Africa. Based on tooth analysis, the fossil is considered that of an adult female. With a cranial capacity is about 485 cubic centimetres (equivalent to that of a male chimpanzee), Mrs. Ples was one of the first fossils (along with the Taung child skull found by Dart) to reveal that upright walking had evolved well before any significant growth in brain size. The fossil has been dated by a combination of palaeomagnetism and uranium-lead techniques to ca. 2.05 million years ago.

Robert Broom

Robert Broom (1866-1951) was Scottish-born medical doctor who became a skilled vertebrate paleontologist in South Africa. In 1903 he was appointed Professor of Zoology and Geology at Victoria College, Stellenbosch. The

College had a conservative religious ethos, however, and in 1910 Broom

was dismissed for his evolutionary views. After establishing a medical

practice in the Karoo region of South Africa, he began to explore the

area which is rich in Middle and Late Permian fossils. Based on

many findings of Therapsids or mammal-like reptiles, and his writings on mammalian anatomy, he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1920.

College had a conservative religious ethos, however, and in 1910 Broom

was dismissed for his evolutionary views. After establishing a medical

practice in the Karoo region of South Africa, he began to explore the

area which is rich in Middle and Late Permian fossils. Based on

many findings of Therapsids or mammal-like reptiles, and his writings on mammalian anatomy, he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1920. While many of his fossil discoveries and most of his publications concerned Late Permian Therapsids, Broom is perhaps better known for his discoveries of hominid remains in the late 1930s. Following the 1925 discovery and publication of the Taung child (Australopithecus africanus) by Raymond Dart, Broom became friends with Dart, and grew interested in the search for human ancestors.

Fig.5: Robert Broom (photo: ca 1910).

Between 1936 and 1938 Broom made several major discoveries in Sterkfontein Cave northwest of Johannesburg. Therse included a complete A. africanus skull nicknamed Mrs. Ples, and a partial skeleton that indicated that Australopithecines walked upright (Broom 1938, 1939). He also discovered the first fossils of the robust australopithecine, Paranthropus robustus, in a cave at Swartkrans, South Africa (Broom 1948; Broom and Robinson 1947, 1952).

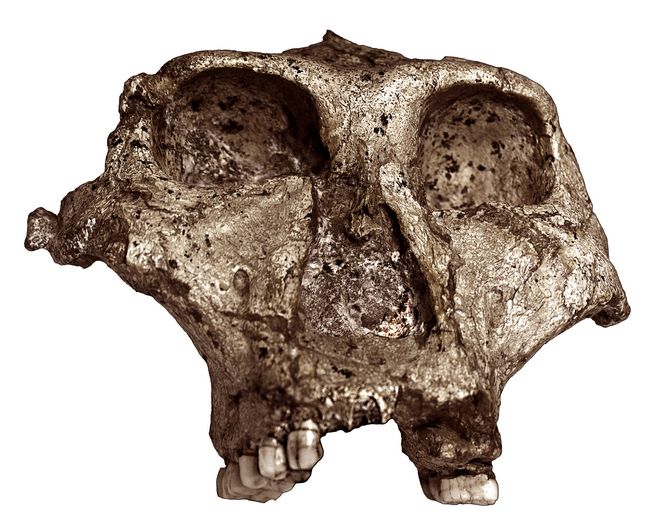

Paranthropus

Fossils of Paranthropus ("near man"), a robust form of australopithecine, were first discovered by Robert Broom in 1938 at Sterkfontein cave in South Africa. Ten years later, in 1948, more substantial findings of Paranthropus including several skulls and jaw fragments were made by Broom and John Robinson at Swartkraans cave, the most complete of which (fig.6) was a male skull (SK-48), now at the Transvaal Museum in Praetoria. The species was originally called Paranthropus crassidens by Broom, but is now called Paranthropus robustus, or Australopithecus robustus.

Fig.6: Male skull of Paranthropus robustus (SK-48) (photo: T

ransvaal Museum)

ransvaal Museum).

A female Paranthropus robustus is represented by a nearly complete skull (sample DNH-7), now at the University of the Witwatersrand). The skull (fig.7), including an articulated jawbone with most of the teeth, was found in 2000 at Drimolen Main Quarry in Guateng Province, South Africa (Keyser 2000).

Fig.7: Female skull of Paranthropus robustus from Drimolen (DNH-7) (photo: Univ. of the Witwatersrand)

Zinjanthropus

Zinjanthropus is an early hominin from East Africa, first discovered at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania in 1959 by Mary Leakey, dating from the Early Pleistocene at about 2.0 mya. The name Zinjanthropus (

"nutcracker man") was coined due to the massive jawbones and teeth of this individual.

"nutcracker man") was coined due to the massive jawbones and teeth of this individual. The holotype skull (OH-5) (fig.8) was originally classified by Louis Leakey (1959) as Zinjanthropus boisei ("nutcracker man from the woods"), but is now reclassified as Paranthropus or Australopithecus boisei, a more massive relation of Australopithecus robustus, first discovered by Robert Broom in South Africa.

Fig.8: Skull of Zinjanthropus or Australopithecus boisei (Yale Peabody Museum cast; photo: Athena Review)

Brain size or cranial capacity was about 450–550 cc, similar to that of other australopithecines. Some skulls are markedly smaller than others, which is taken as evidence of sexual dimorphism where females are much smaller than males. This skull has a sagital crest, providing an attachment for the large jaw muscles. This is more pronounced in male skulls, another trait of sexual dimorphism such as also seen in present-day gorillas, orangutans, and chimpanzees.

.

Homo habilis

.

Homo habilis is an early hominin from East and South Africa, first discovered in 1959 at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania and dating from the Early Pleistocene at about about 2.3–1.65 (mya). The species name, "handy man", was coined by Raymond Dart and Louis Leakey in 1964 (Leakey, M.D. 1971).

Homo habilis is considered a transitional species between the australopithecines and Homo erectus. As in the earliest H. erectus, the brains size of H. habilis had a range from 500–900 cc. H. habilis is associated with the Oldowan flake tool industry, and seemed to mainly use tools in butchering, often scavenging meat from carcasses killed by feline predators.

Fig.9: Homo habilis skull, KNM-ER-1813 (Yale Peabody Museum cast; photo: Athena Review

Homo rudolfensis

Homo rudolfensis is an early hominin from Kenya dating from the Early Pleistocene at 1.90-1.88 mya. The type skull (KNM-ER-1470 at the Kenya National Museum) was found in 1972 by Bernard Ngenyeu Kanyenze, working with Richard Leakey. The species is named for Lake Rudolf, now named Lake Turkana, in Kenya.

H. rudolfensis is grouped in the family Hominidae and the genus Homo. It is considered to be contemporary with the earliest Homo erectus. The status of H. rudolfensis in terms of human evolution remains controversial.

Fig.10: Homo rudolfensis skull (Yale Peabody Museum cast; photo: Athena Review

References:

Berger, L.R., A.W. Keyser, and P.V.Tobias 1993. Gladysvale: First early hominid site discovered in South Africa since 1948. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 92 (1): 107–1

Berger, L R. and W.S. McGraw 2007. Further evidence for eagle predation of, and feeding damage on, the Taung child . South African Journal of Science. 103 (11–12): 496–498.

Brain, C.K. 1983. Who Were the Hunters and Who the Hunted? in The Hunters Or the Hunted?: An Introduction to African Cave Taphonomy. University of Chicago Press.

Broom, R. 1938. The Pleistocene Anthropoid Apes of South Africa. Nature. 142 (3591): 377–339. .

Broom, R. 1939. The dentition of the Transvaal Pleistocene anthropoids, Plesianthropus and Paranthropus. Annals of the Transvaal Museum. 19 (3): 303–314

Broom, R. 1948. Another new type of fossil ape-man. Nature. 162 (4132): 57.

Broom, R. and J.T. Robinson 1947. Further Remains of the Sterkfonstein Ape-Man, Plesianthropus. Nature. 160 (4065): 430.

Broom, R. and J.T. Robinson 1952. Swartkrans Ape-Man, Paranthropus crassidens. Memoir 6, Transvaal Museum, Praetoria.

Clarke, R.J. 2008. Latest information on Sterkfontein's Australopithecus skeleton and a new look at Australopithecus. South African Journal of Science. 104

Dart, R.A. 1925. Australopithecus africanus: The Man-Ape of South Africa. Nature, 115, (2884): 195-9

Dart, R.A. 1949. "The cranio-facial fragments of Australopithecus prometheus". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 7 (2): 187–213.

Dart, R.A. 1953. The Predatory Transition from Ape to Man. International Anthropological and Linguistic Review. 4 (4).

Darwin, Charles. 1871. The Descent of Man

Herries, A I., R.J.M. Martin, et al. 2020. Contemporaneity of Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and early Homo erectus in South Africa. Science. 368 (6486).

Kappelman, J. and J.G. Fleagle 1995. Age of early hominids. Nature. 376 (6541): 558–559.

Keyser, A.W. 2000. The Drimolen skull: the most complete australopithecine cranium and mandible to date. South African Journal of Science. 96: 189–197.

Leakey, L.S.B. 1959. A new fossil skull from Olduvai. Nature 185 (4685).

Glossary